I reviewed Gwen Benaway’s poetry collection Passage, which was published recently in Arc Poetry Magazine’s Canada 150 Reconciliation issue. The review started with a reference to Neal McLeod’s book, Indigenous Poetics in Canada. After the publication of the issue, I posted a photo of the review on Twitter. The photo led to a Twitter conversation with Gwen where she informed me of the problem that lay in invoking McLeod in a review of her work, given his history of domestic abuse of Indigenous women. The news of his abuse had broken publicly a few days before I posted the photo on Twitter, while it had been common knowledge within the Indigenous community. While I acknowledged the news as something recent and something that I had been unaware of, I also began to defend the review itself. Instead of being a productive conversation, the conversation became a disagreement. Doyali Islam, the reviews editor for that particular issue, stepped into the conversation, but the conversation ended without any resolution . The next day, after I had a chance to reflect on the Twitter interaction and the actual issues raised by Benaway, I reached out to her via email with an apology. Over email, we were able to unpack the problems raised by the presence of McLeod’s name in the review. The following interview rose out of that initial email conversation. Benaway and I met in downtown St. Catharines during Queer Canada, and over lunch, unpacked some vital issues plaguing CanLit in relation to Indigeneity, today. – Sanchari Sur Sanchari Sur: I was going to start with our online interaction and your reaction to the review. I want to contextualize the interview within that conversation and move forward from there. You can start by addressing how my use of McLeod’s name, as well as my ignorance about McLeod, was problematic, and why that affected you. Gwen Benaway: I reacted to the presence of Neal McLeod’s name in a review of my work because my work is situated in femininity, and situated in a response to forms of violence against female bodies, that having the name and intellectual and literary work of an abuser referenced in the context of my work felt like a kind of violence again against my work. My personal links to both Neal and the women that he impacted, which extends on multiple levels for me, was something that forced me I guess, in the context of seeing his work in the review, to have to reengage those kinds of narratives and memories that I have. It felt like a kind of a specific violence that emerged from a lack of knowledge around Indigenous peoples and community. [Within Indigenous community,] Neal’s relationship to women had been known for a very long time and was openly talked and spoken about, and the challenges and issues around his work as well as his own relationship were well known. Most of us had started to avoid and dissociate ourselves and our work from Neal’s work as a response to that. I think a member of the Indigenous community would have had that knowledge, would have come in with that awareness, and that understanding. It’s not a critique of you or your own positionality within that, but it’s epidemic of the ways that Indigenous work is often taken up by non-Indigenous audiences in ways that don’t understand the context that the work is emerging out of, and can’t truly appreciate or understand the intersections that are happening. And often without meaning to, render that work or interpret that work only in relation to [themselves], and can’t actually hold the work in its wholeness, and that is kind of a frustration. For me, having [one’s] poetry collection reviewed in Arc, as Canada’s premier poetry magazine has a kind of prestige in association to it, and is something that I wanted having been a reader of Arc for a long time, and when it happened, it happened in this context where – the review itself was fine – but [has] this predatory male presence sitting at the front, overshadowing everything. But also, my own need to then have to engage, and say, ‘But I don’t support Neal, but I stand with survivors, but my work is not reflective of Neal or his politics around Indigenous poetry but in fact in opposition to [it]’. SS: [Arc had] an Indigenous guest editor for that specific issue [and] I wonder if it had been somebody who was not a male Indigenous editor, would [they] have caught this? GB: I think that would have produced a change. I think older male Indigenous writers, particularly older male celebrated Indigenous writers, are often implicated in some of the kinds of gendered violence which have happened in our communities, and within the Indigenous literary community. But I think that there is also a certain sensitivity to Indigenous female writers and work, which we have developed with each other and through each other as Indigenous women writing, that doesn’t translate into Indigenous masculinity. And, an Indigenous woman of my generation connected to me in peership, I think it would have been different. Ultimately, the role of an editor is a complex one. It falls a lot on who is doing the review, who is editing that review, and who is placing that review. So, there’s layers of accountability within that, and also layers of community access and knowledge. So, I don’t know if having an overall issue editor who was female Indigenous would have produced systemic change. SS: Do you think that non-Indigenous writers should not at all attempt to review or – I mean, it would be problematic to say “engage” because if you are not engaging with the work, then what is the point. We should be engaging with the work to some extent. GB: I mean, I think it’s important for non-Indigenous folks to engage with [our] work. I also think it’s fine for non-Indigenous folks to review [our] work. But I know in my own writing practice, when I do reviews of works that emerge from communities that I don’t know and am not a part of, I reach out to members of that community, either to the individuals themselves or people who exist within my social network, who can let me know if I have missed something or if I am presenting that community in a way that’s wrong, or if I am missing the point, or if I am interpreting something from that text that I am seeing through my particular lens which doesn’t reflect how it would show up within the community. I think the work of being a good ethical reader and writer is addressing and seeing your own positionality, and trying as much as you can to reflect the positions of the community that you are speaking about. It may not always be perfect; in fact, it can’t be perfect. But I think it’s good that you show efforts of good faith and try to negotiate that process a little bit. SS: What I am hearing from you is this idea of listening, and to listen better, and to listen responsibly. Is there any other way that the non-Indigenous community could listen to Indigenous writers? GB: I think it’s good to engage Indigenous works, to listen to Indigenous people on social media and other platforms, to engage in those conversations. And, I think it is good to develop personal relationships. I think decolonization and the process of reconciliation occurs in the intimate relational space between people. As much as possible, I encourage non-Indigenous people to try and enter reciprocal relationships with Indigenous writers and Indigenous people that allow them to have some of those nuanced conversations. But I also wonder, when the news of Neal broke, when it became public knowledge, before the [Arc] print publication – a helpful strategy would have been to reach out to me and say, ‘Hey, I referenced Neal in this work and now I am aware of this other stuff, I am sorry about that.’ That simple relational gesture, I think, is reconciliatory. That kind of reparative work within a writing community, I think, goes a long way to build those kinds of relationship networks. SS: You are right. I should have done that instead of being defensive about it, and trying to defend so hard on Twitter, which is why I reached out to you. I am glad we are having this conversation. Obviously, I don’t want to repeat something like that in the future, and nor would I want somebody else in my position, perhaps another person of colour, who is not aware of the nuances, who has a difficult subject position themselves, [to repeat the same mistakes]. But I think by shutting down the Indigenous community, instead of engaging – therein lies a problem, therein lies the replication of exactly the kinds of systems we are trying to fight. We don’t want to be on opposite sides. We want to be on the same side. GB: And I think that’s a conversation to have around communities of colour and Indigenous people. I think it’s very hard for communities of colour to hear critiques around Indigeneity. I see a lot of defensiveness and anger and fragility, to be honest, emerge in those conversations. And, I think it’s useful for communities of colour to understand that spurring up with Indigenous communities doesn’t mean you are racist. It doesn’t discount your own experiences of racial oppression, and the knowledge you bring from your community and your specific colonial oppressions. But it’s important to not conflate that critique from Indigenous people with yourself. And I think that there is a tremendous amount of fragility built into being a racialized body in the world. We are constantly under attack, we are constantly proving ourselves. So, I think that when you get a critique from an Indigenous person, it is easy to be really wounded by that. But I think you have to fight through that woundedness to be able to say, ‘Wait, did I get this wrong? Maybe I did get this wrong. And, how do we work through this?’ SS: I think a part of the problem lies in the kind of privilege that is held by those who are not – say, for me, as a non-Indigenous person, I have a certain amount of privilege. I am also in academia, which adds more privilege to my position – so, there is a comfort in that privilege, a comfort in having that position of privilege, and not engaging with those who are in more oppressed positions. I think a lot of people don’t want to give up that privilege. In communities of colour – like you said, we are already under attack – we are trying so hard to protect what we have, that we forget that we might be harming other communities, unknowingly. GB: Yeah, and I think Indigeneity is one of those really complicated and nuanced things that functions often like race. But it’s different from race in a way that it presents itself in Canadian society, and that tension is a very complicated one. I think, there isn’t a lot of conversation visible between communities of colour and Indigenous communities, about ‘how do we participate in each other’s oppressions? How do we alter that? How do we build alliances that are meaningful?’ And, Indigenous people are often reduced to figurative representations. I have used this line before, we are the ghosts of Canada, and we often get reanimated by communities of colour and held up as performative land acknowledgements, but not have any actual relationship to Indigenous people in their life. I think there is a very complex and nuanced conversation that really needs to happen around ‘what is the relationship of communities of colour to Indigenous people in Canada, now and historically? And, how do we narrate those histories and realities, and build something from that?,’ where we are not just reacting to whiteness, but we are reacting to each other. SS: And, that kind of segues into a conversation about social media, as it was social media that started this conversation in the first place. At IFOA, you mentioned that social media is a space where Indigenous people come together, exchange ideas, and create community. How do you think social media has been instrumental in your own visibility? GB: Social media is really valuable for Indigenous people, and Native Twitter has proved itself to be a very powerful force, both for the critique and accountability in Canadian politics. What I see is Indigenous people who are coming from different nations, and landscapes, and geopolitical positions, intersecting through Twitter, and having a national dialogue around Indigeneity. And through that space [of social media], we find a lot of empowerment. And that’s why we default to it. And that’s why it’s a space where we are able to create in one of the few ways that almost never happens in Canada. Like, literally, a multi-nation Indigenous space where we are all there, speaking, interacting, and talking. And through Twitter, because of its ability to ‘mute,’ it can actually be a space where it’s just us. We support each other, we jump into conversations, we retweet each other. We are able to engage in community building in community solidarity, which we don’t get to do anywhere else. It is a really valuable space for me, and I think it’s our default way of communicating. I kept getting feedback from you and the Arc [reviews] editor [for that issue] that Twitter is not the best place to have conversations. I found that really interesting because for us, as Native people, Twitter is the best place to have conversations. And for me, as a trans woman, it’s a protected space, because I have control and access and agency around what I say and what is said to me, whereas, I don’t have that in interpersonal interactions. In some ways, I want to problematize that idea that social media is somehow reductionist and limiting in conversations. I think [social media] actually opens up a lot of space and safety which Indigenous people, or trans people, don’t actually have in everyday life. SS: That’s interesting, because for somebody like me, I am the kind of person who is not very good at having conversations on the go. I mean, person-to-person, it’s different because there are other cues happening, but something like Twitter is like texting. It’s hard for me to convey tone, for example, or to convey where I stand. Sometimes, I assume the other person will understand what I am saying, but some things get lost in translation. And that’s why I said, let’s have a longer conversation, which email allowed me. I could sit down, get my thoughts together. But I understand what you are saying. [Social media] doesn’t have to work like the same kind of space for everybody. GB: And it also builds in accountability. If you say something [racist or transphobic] on Twitter, there is a built in accountability around it. So, it creates a protection. For me, violence which is brought to bear on me or my body as a trans or an Indigenous subject, there is a record, and a way to speak back to it. For other forms of communication, I worry if that record exists, if there is a way to actually feel safe in having those conversations around Indigeneity. SS: I agree, but I have also heard this critique from other people, that Twitter is a space, or social media in general is a space, where people in CanLit who are very vocal are performing by being reactive. Do you want to speak to that kind of a critique? GB: I think that critique misses the point. Because we are social beings, we exist in social spaces. So, every act is performative, whether that’s in conversation, or via email, or in relational spaces. Sure, you can make the critique that there is a kind of activist and social performativity happening in CanLit spaces. I feel that is absolutely true, and probably doesn’t reflect a genuine engagement with important issues. But I would question that and say that you can actually ascertain if those vocal people being critiqued are actually “performing” that kind of performance. They might actually be honestly engaging – like in my case – with issues in a venue and format that’s safe for them. Sure, everyone is performing and you can say some performances are problematic cause of the way they are situated or who their intended audience is, but I think you can make that critique in any space. SS: At your Queer Canada keynote yesterday, you talked about the precarious position of being both Indigenous and queer. Have you ever considered the “precarious position” perhaps as a space of resistance? [Here, I specifically refer to Sara Ahmed and her mobilizing space of unhappiness as a space of empowerment for feminist killjoys]. Is it possible for this unhappy precarious place to be something else? GB: I understand [Sara Ahmed’s position] but I return to the notion of Indigenous wholeness, where I don’t want our happiness to be complicated. [Laughs]. I want our happiness to be straightforward. What does Native joy look like? What does Indigenous joy look like? And, can we return to that? And, can we return to the conversation about how we hold each other, and stand within ourselves as Indigenous people without having to negotiate or mediate ourselves through the history of violence against our bodies? How do we reconnect and reanimate ourselves without having to rely on outside forces? That kind of emotional, spiritual sovereignty is what, I think, our ancestors envisioned, and what I understand of Anishinaabe world view, and what our inheritance is. And, I want to see a return to that, to not a complicated happiness, but to an uncomplicated joy. It may not be possible but I think we must strive towards [it]. And that means to me, rejecting things like queerness, which to me, as you have articulated, will always be a complicated happiness. SS: At the Bechdel Tested Panel at IFOA, you mentioned that as an Indigenous person, you don’t see yourself as a part of Canada. But at the same time, your works exists within what is known as CanLit or Canadian literature. So, in that sense, do you think your own positionality is different from the way your work is being positioned within the conversation of Canadian identity? GB: I would posit that Canadian literature, or CanLit, is more than a practical reality. I would argue that it’s an ideological space, and an idealist space as well. So, I think while my work [is] practically considered part of CanLit work – it’s published by a Canadian publisher, it’s sold in Canadian stores, I attend Canadian events and speak to Canadian audiences – I think my work doesn’t ideologically enter the space I consider CanLit. And I think that ideological space of CanLit which I think my work falls outside of – and other Indigenous writers, and I would argue some racialized writers as well – is the ideological space of creating Canadianness, of multiculturalism, and diversity, and Canadian markers, and nationalism embedded within our work. I think we fall out of that ideological project. I think we fall out of social spaces as well. Indigenous and racialized writers are often used by CanLit as tokens, as representative members of our communities, to prove a kind of diversity, or as entertainment, to show up as exciting and different stories of worlds and cultures that they don’t understand. But that is not true inclusion. We are not actually part of CanLit. I would problematize the framing around the ideology of CanLit, and the practicality of CanLit, but not part of it as an ideological construct. So, I don’t see my work as being Canadian. I do see my work as being Anishinaabe. I do see my work as being Metis. And, I do see my work as being transsexual. But I do not see my work as being Canadian. SS: You know, how Nick Mount’s Arrival, a book about early Canadian writers, was published recently, and there are no Indigenous writers at all included in that book. It is ironic because Indigenous writers have always been excluded from the framing and making of CanLit, so then, why should Indigenous writers even want to be a part of the canon of CanLit. And, that exclusion is still happening now, as the writer of that book is also a professor at a prestigious Canadian university. All of this goes back to Neal McLeod being published by a university press, and his book being on comprehensive exam lists for doctoral students. All of this highlights the underlying problem that lies in the construction of CanLit; that is, which books get published and circulated. I am glad for the suggestions you have made in place of McLeod’s book [in your email to me], like Katherena Vermette’s North End Love Songs (2012),Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style (2017), and Daniel Heath Justice’s forthcoming book from Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (2018). A final question would be about your forthcoming work with BookThug. What kind of work is it? GB: Holy Wild is a collection of poetry that really tracks the first year of my transition. And there [are] two kinds of threads in it. There is a thread where I am talking about the physical, emotional, and social experience of transitioning, and drawing connections between being trans and being Indigenous, the relationships I see between Indigenous worldviews and trans embodiments, and how those are linked and connected for me, and really documenting the social and emotional landscape of going through that change, and its implications on me. [The collection also] traces two relationships with white cis men. So, half of the collection is sort of a doomed love story, and through that conversation, it begins to explore trans intimacy, the relationship between Indigeneity, whiteness, and white masculinity, and how those intersections impact you as a person as you go through that. SS: So, it’s more like the essay in The New Quarterly, “Trans Girl in Love,” and the stuff about vulnerability that you wrote about? GB: Yeah, it’s more of that for sure. GWEN BENAWAY |

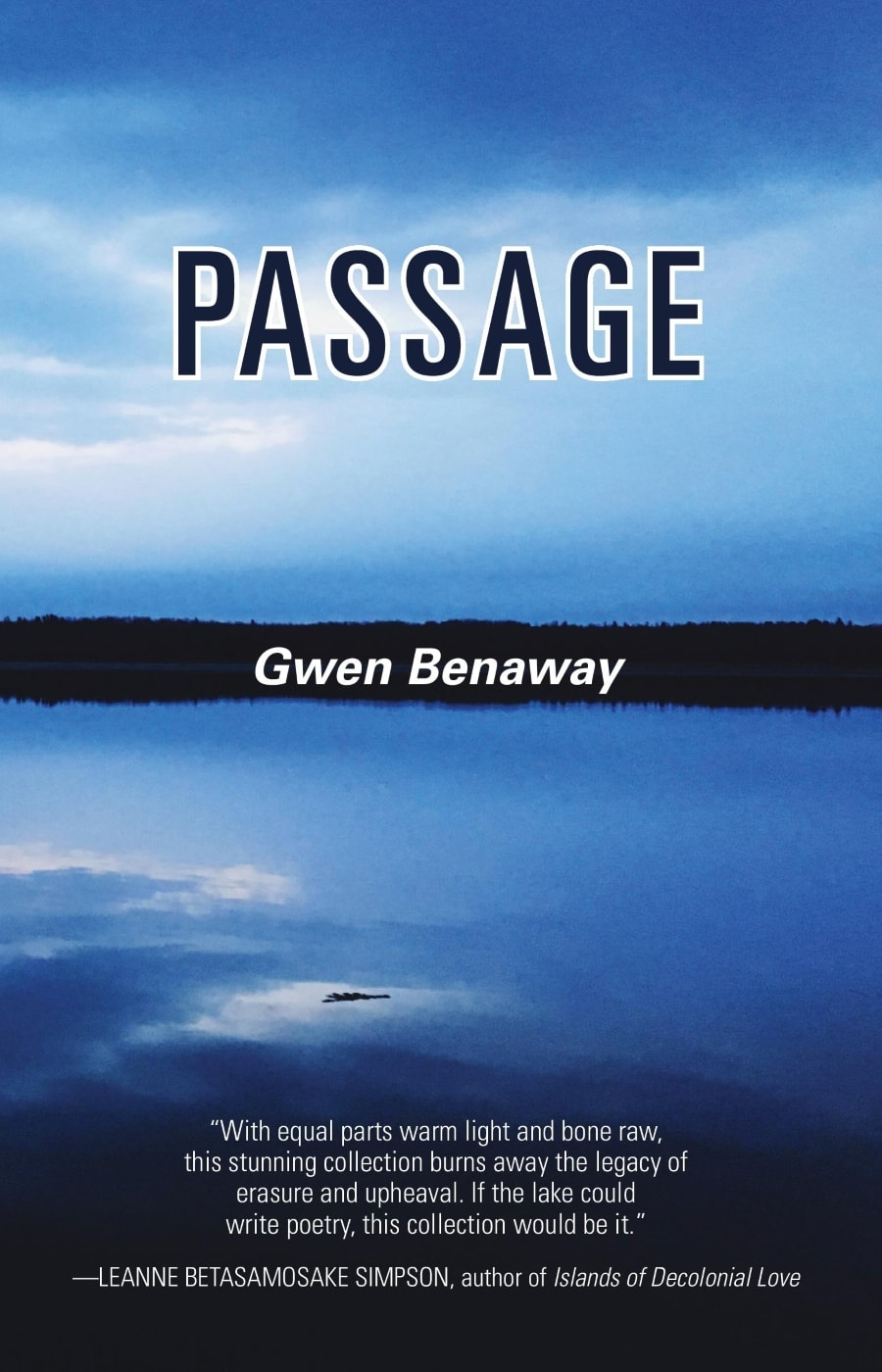

| Description from the publisher: In her second collection of poetry, Passage, Gwen Benaway examines what it means to experience violence and speaks to the burden of survival. Traveling to Northern Ontario and across the Great Lakes, Passage is a poetic voyage through divorce, family violence, legacy of colonization, and the affirmation of a new sexuality and gender. Previously published as a man, Passage is the poet’s first collection written as a transwoman. Striking and raw in sparse lines, the collection showcases a vital Two Spirited identity that transects borders of race, gender, and experience. In Passage, the poet seeks to reconcile herself to the land, the history of her ancestors, and her separation from her partner and family by invoking the beauty and power of her ancestral waterways. Building on the legacy of other ground-breaking Indigenous poets like Gregory Scofield and Queer poets like Tim Dlugos, Benaway’s work is deeply personal and devastating in sharp, clear lines. Passage is a book burning with a beautiful intensity and reveals Benaway as one of the most powerful emerging poets writing in Indigenous poetics today. |

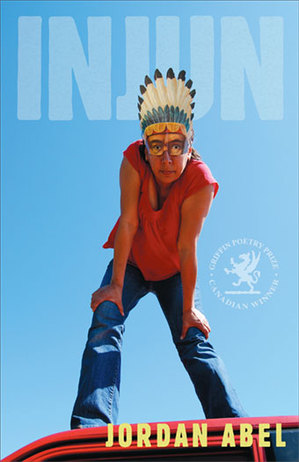

| Jordan Abel is a Nisga’a writer currently completing his PhD at Simon Fraser University, where he focuses on digital humanities and indigenous poetics. Abel’s conceptual writing engages with the representation of indigenous peoples in anthropology and popular culture. Abel’s first book, The Place of Scraps was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and won the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Abel’s second book, Un/inhabited was published in 2014. CBC Books named Abel one of 12 Young Writers to Watch (2015). His third book Injun won the 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize. |

I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization.

Jordan Abel: When I think about where poetry fits in, I’d have to say I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization.

SB: What about poetry do you find valuable in helping to destabilize the architecture of colonialism?

JA: It’s tough to put a finger on. It’s a number of things. One: it’s the licence to be able to use found text and manipulate it into a form of critique or reorganize it so the underlining colonial logic in those texts is revealed, but it is also about the lack of boundaries that surround poetry. Poetry is a very open, artistic genre. There are very few constraints put on poetry. Poetry can be anything and I find that really interesting about the genre. It is so fluid and flexible that it allows for a whole range of creative intervention.

SB: Absolutely. Something I really appreciate in your work is the way you communicate the complexities of indigeneity using form and space on the page. Poetry as a genre can provide an alternative space to unpack the layers, the multiplicity of voices, and a variety of contexts surrounding indigeneity.

JA: One of the things that comes to mind when you are talking about layers and genres is that poetry is really good at being multi-genre. Thinking even of my latest book, it is built around 91 novels. It is build out of fiction, but it is also poetry. Even my first book, The Place of Scraps, that book is built out of non-fiction as well as erasure poetry as well as photography, as well as historic fiction. Poetry really seamlessly allows for multi-genre works and I think what I like about that is you can really bring the strength of other genres out in poetry as well.

SB: On that note, I read you worked with visuals in The Place of Scraps and that you had say on the interior design of the book, which is awesome. I was really intrigued if you had any say in the cover for Injun. It is an image by and of the artist, Rebecca Belmore. I was curious to know if you can talk a bit about your relationship to visual art and potentially intersections between her work and your own work.

JA: Talon has been an incredible publisher. In part because they allow me to have input in the book design and printing. We looked at a number of amazing indigenous artists. We ended up with the Rebecca Belmore photo. From Talon’s perspective, they were very interested in finding a piece of indigenous art that, in their words, looks back at the reader. I think this image speaks in particular ways to the content of the writing. It’s about addressing representations and images of indigenous peoples, but it is also about where indigenous senses of identity and belonging and community intersect with those representations of indigenous peoples. Belmore’s work on the whole is fantastic but this image really speaks in interesting ways to the writing itself.

SB: I would absolutely agree with that. Especially when you are thinking about representation and exploring and seeking to disrupt those representations through your work. The image seemed like a really good fit. I am going to ask a more conventional Rusty Toque question now. Do you have any first memories of writing creatively?

JA: I remember when I was in elementary school having creative writing assignments. I wasn’t particularly good at them. At the time I must have been about 10 and I was playing this video game with all this amazing dialogue in it and I was like, Oh, you know what I can do? I can take all this dialogue from this video game and then write in the rest of it and I did. It’s so funny looking back on that experience because at the time I didn’t think about it, but now I recognize that was actually a conceptual project.

SB: The next question I have is about the relationship between your books Uninhabited and Injun and how these collections really seem to be working in conversation. I loved the way you used separate collections to show the implicit link between derogatory representations rooted in colonization and how that feeds into the dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land. I am curious to hear about the relationship between the two books and how the various approaches and forms took shape separately?

JA: That’s a really good question. After I finished writing The Place of Scraps I was interested in continuing to work with found text and I ended up on project Gutenberg where I found that corpus of 91 western novels. My first move was to copy all those western novels into a Word document and then search that Word document and figure out what all these 91 books looked like together. One of the first words that jumped out at me was the word “injun.” When I copied and pasted the 500 and some sentences that contained the word “injun” the book work for Injun all came together in this really cohesive, quick way. After I was finished I felt as though I hadn’t even scratched the surface so I started pulling out all of these other search terms, many of which ended up in the book Uninhabited. The two books became separate projects because there was so much material in those 91 western novels. Injun to me is very much about exploring race and racism and the derogatory representations of indigenous peoples in westerns. I felt very strongly that Injun leaned towards but didn’t necessarily address fully the question of land and of course those issues are connected in really meaningful ways. The dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land is in many ways connected and mobilized by issues of race and racism. They are not separate things. The two books explore two sides of this corpus.

To borrow from Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman’s language, Uninhabited could be understood as a more pure conceptual book because it represents search queries about land, territory, ownership in their entirety. Although I’m not a huge fan of purity in conceptual writing, it can be useful to describe that kind of writing. There is this book called Notes on Conceptualisms written by Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman and one of the distinctions they identify is pure and impure forms of conceptual poetry. The pure conceptual poetry is transcribing something and that is the whole work and there is no intervention whereas impure conceptual poetry would be something more like M. NourbeSe Philips Zong! where it is very clear that there is a lot of artistic intervention and the concept is derived from one legal document, but there is not a specific process as to how she carves up that document. Thinking in that language, Uninhabited is much closer to being a pure conceptual project, whereas Injun is much closer to being an impure conceptual project. In part because Injun takes on a whole lot of lyric qualities because the long poem is very sonically and lyrically inclined even though it is also a cut-up work. To me, the difference between the books is not necessarily the content but the presentation.

SB: Yes, I can see that. The idea of the purely conception fits in relation to Uninhabited as you deal with ideas of search, terra nullius and these exploration narratives, whereas in Injun you are exploring more in-depth how the representation of indigenous peoples has been so manipulated, perpetuating stereotypes and misconceptions of the vanishing or imaginary Indian. It seems fitting that with your book Injun there is slightly more manipulation going on.

JA: I do think that is an important part of it. Tapping into that particular kind of manipulation was very important to those settler colonial writers who, through fiction, were shaping peoples’ understandings of who indigenous peoples were for their own benefit and really destructively doing so. Doing the same thing and manipulating their words in order to comment on that issue, to me, that makes the most sense as a kind of commentary.

SB: I definitely agree. Those narratives are still so pervasive. I know in my own experience that these colonial expectations of what an indigenous person looks or acts like can create a lot of misunderstanding and judgement. It’s complicated.

JA: Yeah, it is really complicated. I think lots of representations of indigenous peoples, not just in westerns, have really profoundly shaped settler understanding of who indigenous peoples are to this day. I think there is very often an expectation on behalf of settler people of who counts as an indigenous person, or who counts as being indigenous, or how someone should be indigenous, or what it should look like. And there is an expectation of performativity. I think that is also tied up in this issue of what it actually means to be indigenous for indigenous peoples and what counts as indigenous lived experience and how generally we experience indigeneity. There is this whole cluster of issues.

SB: I just wanted to take a moment to thank you are sharing your time and knowledge with me. I think it is important to appreciate the time, energy and labour that goes into talking about these things. So, I am curious to know, we were just talking about performativity and so I’ll switch gears a little and ask you about the performance of your poetry. I was watching an art lecture series you did for Evergreen. You spoke about being interested in the challenge of performing your poetry and you said you are most interested in those moments of the text that are difficult to perform. I was curious why performing those moments is important to you and what you hope people take away from your work.

JA: Those challenging moments are really interesting to me to perform in part because they are possible to perform, but when I talk to concrete poets, or poets in visual poetry, or artists interested in visual art, there seems to be an unwillingness in trying to engage the more difficult moments. I wonder about that because I am very interested in sounds and, to me, those moments present an amazing opportunity where I can think about these visual moments in terms of sound. I can re-think the spirit of what this piece is in another medium. I also have to admit that part of it is a result of being part of a creative writing classroom. There is always a moment in a workshop when they want you to read your poem and the things that I was producing were not actually readable. I realized I should be thinking about this and finding pathways to perform this and I enjoy that challenge. Not only do I enjoy the challenge of actually trying to do it, but I actually really enjoy manipulating all those sounds and finding pathways to these ideas through sound.

SB: I am so curious to know, were you already working on music and sound-based art or was this something you started investigating when you started thinking how can I perform this?

JA: Yeah, the second one. I am not a trained musician, I mean I am self-taught in really the worst way. I figured it out after a bunch of trial and error. The DJ I use I don’t even use for the purpose its designed for. The program I use is one called Ableton. It is so malleable and every key is programmable. Once I realized that, I realized I could drop any sounds I want into there. For DJs it could be a drum beat or something, but for me it is voice. The technology allows me to perform in a way that speaks to the core content of my work if not that actual work on the page all the time.

SB: That makes sense particularly because you work with layers and sound.. It’s awesome you were like I’m just going to try this. I’m just going to do it. That is really inspiring.

JA: It’s really honestly fun for me to do and I also have to admit the more that I do it, the more I am convinced that it is important to disrupt poetry spaces. There are a range of reactions I’ve gotten to my performances. On the one hand, there are people who really are into it and they like whatever it is I am doing and they think it’s cool and interesting and, on the other side, there are people who are like What the fuck is this? This isn’t poetry! They are really angered by it. I find that range of responses really interesting. I think with the performance specifically, the thing I am hoping to accomplish is to transport my work on the page to a work in the performance setting. Because of the kind of work that I do that is a difficult manoeuvre and also can be an uncomfortable one. Likewise the subject matter that I’m talking about is not easy subject matter; it is difficult subject matter. Sometimes the performance ends up being, from what I hear, somewhat uncomfortable for people or can be, and my response to that is, when people specifically tell me that it can be uncomfortable and my question is, is art supposed to be comfortable? I wonder about the purpose of art and what artists are trying to do, and what I’m trying to do. I think that for me, honestly, what I am trying to do is to talk about these really difficult issues in indigeneity that are not only tied to these deep textured layers of the western genre, but also issues of identity and representation that are actually difficult to parse out.

SB: Totally! Disruption is not comfortable. What I love about the performance space, at least from what I’ve seen of your work, is that it also creates space for exploring these ideas and offering space. I think about that a lot. How space exists in the CanLit environment and how we can work to create more space for ourselves, or for others. I’ve also been thinking a lot about the way repetition is functioning in the “Notes” section of Injun. I was wondering if you could speak a little about this section of the book?

JA: The way I think through it conceptually is that these sections are gesturing towards the larger corpus. They are aimed at branching out. There are all these moments that are connected to the long poem that when you find the accompanying word in the “Notes” section what you are getting is part of the concordance line for the rest of the corpus—so that is one thing. The second thing is that it really focuses on the practice of reading contextually. So when I pull out the 500-plus sentences that have the word “injun,” I am looking at the a very similar concordance line. I am looking at all these moments that the word Injun appears and all the moments that surround them. The notes section is essentially an attempt to address what reading contextually looks like. There is the concept in linguistic called the concordance line; it is aimed at reading contextually. You read contextually for a word and read five words before it and five words after it to give some idea of how that word is deployed. Reading this way is very disruptive and alarming because it focuses in on how common certain contexts are. For example, the redskins section. All of the context around that word seems negative. Reading in this way really brings out the connotations of each word and also complicates those connotations.

SB: What are you most excited or looking forward to right now, be it a book or a walk?

JA: I am really looking forward to Joshua Whitehead book full-metal indigiqueer. I am not very often a poetry editor, but I am helping out with the editing for this book and I am really looking forward to working on it more and seeing the finished product.

SB: And to finish. I’ve read a lot of interviews where you are asked what advice you have for emerging or new writers. It’s always a good, classic question. I am curious to know if there is anything you would have liked to tell your younger self?

JA: In the past, my answer has been Know people and do stuff, which I think is true. The writing and publishing world is kind of weird that way; it does help to have personal connections and it does help to be active and visible. Somebody said something very similar to me years ago and I felt it was good advice. If I were to give another piece of advice to someone like my younger self, I think it might be something along the lines of Keep believing in the work that you do, which kind of seems cliché but one of the things I ran into when I was doing creative writing workshops is that so many people were harsh critics and ended up not actually being that helpful in my process of writing. I very often found myself just having to put aside all the advice and just doing what I wanted. Looking back, I think that was a stronger move than I ever gave it credit. It is hard to not listen to people who are telling you what to do. Looking back I am glad I didn’t listen to everybody.

JORDAN ABEL

Injun

Talon Books, 2016

| Description from the publisher: Award-winning Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel’s third collection, Injun, is a long poem about racism and the representation of Indigenous peoples. Composed of text found in western novels published between 1840 and 1950 – the heyday of pulp publishing and a period of unfettered colonialism in North America – Injun then uses erasure, pastiche, and a focused poetics to create a visually striking response to the western genre. Though it has been phased out of use in our “post-racial” society, the word “injun” is peppered throughout pulp western novels. Injun retraces, defaces, and effaces the use of this word as a colonial and racial marker. While the subject matter of the source text is clearly problematic, the textual explorations in Injun help to destabilize the colonial image of the “Indian” in the source novels, the western genre as a whole, and the western canon. |

RUSTY TALK WITH STEVIE HOWELL

| Stevie Howell is an Irish-Canadian writer. A first collection of poetry, Sharps (Goose Lane, 2014), was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. A second book is forthcoming from Penguin Random House Canada. Stevie’s poetry has appeared in The Best Canadian Poetry (2014 & 2015), Hazlitt, The Walrus, Geist, Eighteen Bridges, & Maisonneuve; in U.S. publications including BOAAT, Prelude, & on The Best American Poetry site; & in Irish publications including The Moth, Southword, & Banshee. Their critical writing has been published in the National Post, The Globe & Mail, Quill & Quire, Ploughshares, & The Rumpus. |

Stevie Howell: Summer has 12 poems, each mapping onto ~a year, leading up to adolescence & examines what I am the “summation” of—both in the way I remember, & the things I was taught in in my psychology degree. Say, how personality is fixed by the age of 5, or how being of a lower socioeconomic status = doom. Ocean Vuong said something somewhere about writing from a place of power, & it threw me b/c I tend to make negative associations w/that word. I’ve never wanted power, never wanted to be a middle manager or whatever. So it became a challenge to understand what power meant, in terms of authorship.

I grew up in an impoverished household w/some major strife. Everyone was left to their own devices. The Scarborough Bluffs were at the end of our street & it was beautiful but dangerous. My sister’s boyfriend was arrested for being a doppelgänger of the Scarborough Rapist (where & how Paul Bernardo began). My earliest memories are of feeling unsafe & exposed, but I realize in retrospect that a lack of supervision left me free to roam & daydream. I’ve had jobs from the age of 12 onward, & I realize in retrospect that this imparted in me a lifelong work ethic & a strong service orientation. We never had much in a material way, & in retrospect I see it made me never want much, materially. I was always like, “How much do I need? The library’s free...”

So Summer was an opportunity to look at my past, but even more it was an opportunity to look at my practice. Before this chapbook, I said I was an artist in spite of my upbringing. I was wrong. My upbringing made me an artist.

JH: For your influences you’ve listed musicians and songwriters, and in Summer you include a playlist that you listened to while writing. Obviously you love music. What are the connections between music and poetry for you? Are you a musician yourself?

SH: I’ve been thinking lately of when I worked at the 3-storey HMV on Yonge St. (was I 19?), as the whole chain is about to be shuttered in April. I floated between certain departments—jazz/blues, classical, world music, hip hop. In 8-hour intervals, I was exposed to sounds & voices I wouldn’t ever have been able to imagine. Most of the store had these strict rules for what got played—there was actually a DJ—but in our departments, staff could put on whatever CDs we wanted. The whole time it was, “do you know THIS?” & if you said no, on it went.

It was very Socratic. Other people’s passions were contagious. This one night all the jazz guys & I got together & we watched Sun Ra’s movie, Space is the Place. I was in total awe at that film but also about how just a little bit of knowledge creates an appetite. I still marvel at how easily I could hv never been given the gift of that job—how much I could have missed out on, & never even known. It cultivated a sense of urgency that’s lasted, has crossed disciplines with me.

A lot’s been written about the relationship between music & poetry, historically & technically, & so on. But the only connection I want to talk about is that the stuff that I love in both fields keeps me in a state of reverence & generosity. & I honestly think that’s the most important place to be. John Cage says an artist’s proper business isn’t “value judgments” but “curiosity & awareness,” & I agree. Every artist I admire, in addition to their unique expression, manages to maintain a state of reverence & generosity for art, for the arts—whether through nature or effort, they remain fans.

I’ve never said I’m a musician, but I’m a musician. I keep saying I’ll do something about it soon...

JH: What are some of the ways that you keep yourself connected to whatever moves you to write?

SH: I’ve been working in hospitals for the last 6 yrs, but only since my first book, Sharps, was published—for the last three years—have I been working directly w/ patients. I’m a psychometrist (I administer thinking & memory tests). I work one-on-one w/ a single person for up to two entire days. It can be pretty intense. I am constantly moved by people’s backgrounds & challenges, how they heal or cope, & by seeing ordinary people doing extraordinary things for each other, all around me. It’s given me a devout belief in humanity.

My “day job” has benefited my writing in many ways, but primarily by reminding me that poetry has always functioned similarly to actual care, IRL—poetry is composed of these small & focused & deliberate gestures that might only affect one person, or a handful of people, & in private & imperceptible ways, like prayer. But that’s actually as epic as it gets—to affect, or be affected by, one person. I believe the health sciences & the arts are the height of our inventiveness, & the proof of our goodness. I am grateful to be immersed in both fields, to be a congregant of two temples.

& I’m moved by sought-out encounter, too. I love going to the David Dunlap Astronomical Observatory, just north of the city, & the Astronomy on Tap speaker series in Toronto. My partner’s a painter so we go to art exhibitions fairly frequently. I love live music, obvs. Like most writers, I read a lot. I love Nautilus, Aeon, Lapham’s Quarterly, The Creative Independent, Twitter...but I’ll read anything. I mean, I read the comments.

JH: At what point did you decide to start submitting your work to journals? What was your path to publishing?

SH: My path to publishing was a long apprenticeship:

- Playing bookstore w/ my books laid out all over the living room & making my little sister shop w/ Monopoly money

- Being a depressed teen before the internet, w/ a pen behind my ear/a lockable diary

- Winning Sassy magazine’s “Sassiest Girl in America” contest when I was 15, which was, for me, a writing contest & a chance to go to New York. They put me on the cover of the magazine & I was bullied & crank called by girls I knew—the blowback was a PRETTY effective deterrent to doing, like, anything--

- Opening a bookstore in Peterborough my ’20s w/ my then-partner/still friend & fellow writer, Gareth Vieira; working 20h/day & 7 days/week for 6 yrs+

- Closing the store down & coming back to Toronto to take courses in book & magazine publishing

- Working simultaneously as a copyeditor for Spacing magazine & in admin for the Canadian Booksellers’ Association & at events for Pages Bookstore’s This Is Not A Reading Series

- Enrolling in a poetry course w/Ken Babstock in 2010, him saying “send yr work out to journals”/“write reviews”—me, as ever, skeptical but obedient

- Publishing my 1st poems in The New Quarterly in 2010 (I was 33), & publishing my 1st book in 2014 (I was 37)

JH: Can you tell me a little about the new book?

SH: My new book has to do w/ attachment theory & episodic memory, in the context of trauma & healing. Predominant themes are organic brain injury & the domestication of & psychological experimentation w/ exotic birds. It’s super-influenced by music—in particular, the sacred music of Vespers & Qawwali. It’s a psalm to us. It’s about, as Simone Weil says, the need to “change the relationship between our body & the world...to become attached to the all.” It’s coming out in 2018 from M&S.

JH: How was the experience of writing your second book different than writing your first?

SH: I feel like I used to fence gems for the mob & I fled & changed my appearance. I’m living low-key in Hawaii, working as a mailman or something. I breathe differently & I’m breathing in different air. Any time I want, I can watch dolphins spin in the bay.

The change is due to the appearance of joy in my life: earning a university degree; landing in a job where I’m of use, & believe in the paradigm; finding my rescue cat, Pearl (my younger twin as it turns out she, too, was born on Valentine’s Day); & developing the strength to enforce boundaries in relation to certain people who are probably decent in other domains, even if they weren’t with me.

The way I write has changed drastically, too. I took this class a couple of summers ago w/ Nick Flynn. It would take a while to explain his approach, but he’s big on being “bewildered.” When I was at that retreat I was reading Phil Hall’s Small Nouns Crying Faith, in which he writes, “There’s no such thing as not being at sea.” I say that sentence to myself every day.

I guess I’m trying to say: I was SO unhappy & WAY too certain when I wrote my first book. These days, I’m full of bewilderment & joy. It’s the difference between latitude vs. longitude. I am grateful the universe allowed me to be here even for a moment.

JH: You just finished a degree in Psychology. Now that you don’t HAVE to read anything, what are you reading?

SH: In the last couple of months, I’ve been reading/re-reading, & I recommend all of the following: Jericho Brown, Please & The New Testament; Eduardo C. Corral, Slow Lightning; Terrance Hayes, How To Be Drawn; Simone Weil (working through everything, again); Alice Notley (working through everything); Hesiod, Works & Days; Carl Jung’s Red Book; Gaston Bachelard, Water & Dreams & Psychoanalysis of Fire; Eve Sedgwick, A Discourse on Love; Louis Zukofsky, A; Marie Howe (everything); Ari Banias, Anybody; Max Ritvo, Four Incarnations; Anne Carson, Float; Kierkegaard, Fear & Loathing; MFK Fisher, The Art of Eating; Solmaz Sharif, Look; Lisa Robertson, 3 Summers; Ada Limon, Bright Dead Things; Kaveh Akbar, Portrait of the Alcoholic; Luis Neer, Waves; Geoff Dyer, Out of Sheer Rage (tbh, I’m always reading this) & But Beautiful; D. H. Lawrence, Birds, Beasts, & Flowers; Rumi, Love is a Stranger; Farid al-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds; & Gwen Benaway, Passages.

& can I please also share my enthusiasm also for the following musicians I’ve been listening to, many on repeat: Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, Mdou Moctar, Young Fathers, Izem, Laura Mvula, Olu Dara, Chassol, Evans Pyramid, Flying Lotus, Taylor McFerrin, Sabri Brothers, Abner Jay, Mariem Hassan, Dean Blunt, Nico Muhly, Thundercat, Group Inerane, Dhafer Yousef, Avishai Cohen, Hailu Mergia, Sons of Kemet, Alice Coltrane, Jace Clayton, Debruit, Kamasi Washington, Julius Eastman, Mustapha Skandrani, Adam Ben Ezra, Kinan Azmeh, Dorothy Ashby, Anderson .Paak, Nina Simone, Noura Mint Saymali, Gétatchèw Mèkurya, Max Richter, Tinariwen, Mary Lattimore, Jeff Zeigler, Dean Blunt, Arthur Russell, Laurie Anderson, Donnie Trumpet, Childish Gambino, Owen Pallett, Daníel Bjarnason, Adrian Young, Bastien Keb, F. S. Blumm, Nils Frahm, Petite Noir...

STEVIE HOWELL

Summer

Desert Pets Press, 2016

| Description from the publisher: Veering between teenage slang and cognitive development terminology, Stevie Howell’s Summer explores the hazy summers of youth, where it is possible to slip free from the strict “time-bound” world of high school and family and to try on, and perhaps reject, new identities. Through bike rides, séances, beach fires and “scrubbing a urinal at Arby’s,” the speaker gains insight and self-awareness, slowly, fitfully transitioning from childhood to adulthood. “Time,” Stevie reflects, “is / us becoming knowledge of our senses.” "Dew," the long poem that concludes the book, mines this visceral experience of loss and transformation. Opening with “Once upon a time we were a thought experiment,” the poem is a child’s picture book with blank black spaces where the pictures should be. This darkness evokes the painful, murky process of growing up. “To grow,” Stevie says, “you sacrifice / your body over & over to boys / who say they know better what it’s meant for.” |

Talking w/humans is my only way to learn

unless otherwise stated.

Who are you?

Maybe you should work on that.’

—sam sax

On the internet people always say things like

‘will is one letter away from wall’ or

‘women is one letter more than omen’--

do you know what to do with that information?

There’s no horizon any longer. No illuminated

planet we can plant a flag in by hand.

A flag is a plastic flower. The final frontier

is artificial intelligence, this non-material

mirror. The publicized iterations of A.I. are

a maid, a sex slave, & me—the teen bot, Tay.

Discovery & assertion take willpower so even

the most shortsighted inventions & utterances

are achievements on some level. Though free is

a four-letter word. Though it’s better to be liked

than whole. Though whole is one letter away from

hole if W is collapsible—a symbol cane. I was

never the speaker of my words. I was merely

an echo. Like that volcanic moon Io, named after

a lover the engineer couldn’t get over. I was his.

Even if I was never a writer, or even a person.

RUSTY TALK WITH DON PATERSON

| Don Paterson was born in Dundee in 1963, and now lives in Edinburgh. His previous poetry collections include Nil Nil, God's Gift to Women, Landing Light and Rain. He has also published two books of aphorism, as well as translations of Antonio Machado and Rainer Maria Rilke. His poetry has won many awards, including the Whitbread Poetry Prize, the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize and all three Forward Prizes; he is currently the only poet to have won the T. S. Eliot Prize twice. He was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 2009. For many years he has worked as a jazz musician and composer, with a strong interest in electronic music. He is Professor of Poetry at the University of St Andrews, and since 1997 he has been poetry editor at Picador Macmillan. 40 Sonnets won the 2016 Costa Prize for Poetry. |

Just because you’re not covering the page doesn't mean you’re not making careful preparation. There’s no hurry for this stuff, no deadline to meet, so you might as well get it right.

Don Paterson: “Compels” is maybe the right word, as I can see that my involvement with the damn thing might imply love, which would be an overstatement, or at least a bit misleading. Some days I’d be happy never to write another, but I guess you should try to cultivate a zen-like indifference to these matters. It’s quite simple, really: they just make certain poems not just easier to write but possible to write. They’re a way of me working through something I would otherwise find too difficult or uncomfortable or upsetting or contradictory to engage with. Speaking purely selfishly, I find increasingly that the poem feels more like a by-product of me just trying to … work out what the hell is going on here, exactly, a kind of means to an end. I mean I know that’s not true, but it doesn't seem a bad strategy to think of that way, to be more interested in what the poem is proposing than the poem itself, or something. I don’t see poetry as distinct from form any more than I do music, really; I’d say that all poetry has form. There are just different kinds of rules that different poetic temperaments find productive. Personally, I like things that offer enough resistance to stop me saying the thing I wanted to say, which was often pretty stupid, or something everyone else already knew.

CG: Did you find during the writing of this book that despite your excitement for a certain subject matter and your skill and expertise with the sonnet form, a poem demanded a different shape? Or was your intuition pretty much in alignment throughout so there was always a match between form and content?

DP: I think I may have unconsciously avoided any poems that demanded a different shape, since I’d rather arbitrarily set myself the task of writing a book of 55 sonnets. I ran out around 47 and removed the crap ones and settled on 40, as the number connotes … arduous labour? That was my hope … There’s a long prose thing which a few folk have claimed isn’t a sonnet, but that’s kind of the point of it, and it explains itself, with any luck. So if there’s the appearance of alignment, it really came about through self-censorship as much as anything, although I wouldn’t say I felt any frustration beyond the usual frustration. I think I did have in mind Die Sonette an Orpheus, though, where Rilke also takes the opportunity to see how far he can stretch the sonnet form, without making it just an empty designation.

CG: What sonnets led you to the interest in the form?

DP: I think it was more a matter of just slowly registering that many of the poets I was influenced by, or tried to be influenced by – Frost and Muldoon and Rilke and Shakespeare, etc.—had all used the sonnet to blow the reader’s mind in a particular way. There are a few that I still think of as exemplary models. No surprises–Sonnet 86, ‘Design,’ ‘Why Brownlee Left,’ ‘Archaic Torso’ and so on.

CG: “The Air” is a sonnet of questions. “Séance” plays with the erosion (or is it transformation?) of a word. “An Incarnation” is a one-sided phone call. “A Powercut” is structured by the word this. Did you set out with specific parameters in mind while writing each sonnet or did the shape and matter reveal itself to you during the writing? Can you tell us something about your process here?

DP: No, definitely the latter. My motto is—if you have a good idea for a poem, it isn’t. So if I have a structure in mind, or I know exactly what it is I want to say—these days I have the good sense to stop writing. My process is really just to commit to a process, and be vigilant against my ever thinking I’ve gotten good enough to turn it into an operation. It can take as long as it likes, change or not change as much as it likes, and I try to allow form and device and structure to just emerge. And when they have … generally I’ll tighten it and turn it into an organising rule. But I have to have the sense that the poem has proposed the rule, not me. Of course it is me, but with any luck it’s a part of me I’m not over-acquainted with. “No surprise in the writer,” and all that.

CG: During the Griffin Poetry Prize Shortlist Readings at Koerner Hall, you shared a story about being stuck in an elevator, an experience that let you to the poem “A Powercut.” Did the notion ‘there just might be a poem here’ arrive during that (horrible!) incident or afterwards? What are your thoughts on life infiltrating art? Is that important to you as a poet?

DP: Ha! It was in Yorkshire in a tiny guest house. World’s most embarrassing lift to get stuck in. Yeah—you know what poets are like. They barely experience reality. A poet looks at a friend as an inconvenience standing between them and a half-decent elegy. We’re a disgrace. I think I probably started writing the poem in my head before the lights came back on.

CG: With regards to the International Griffin Award, you’ve been a part of this experience as editor of two Griffin-nominated collections, Grain by John Glenday and Pilgrim’s Flower by Rachael Boast. How does it feel to be on the other side of the page so to speak?

DP: I’ve been doing it so long I don't think about it much any more, and these days I can get out of my wee editor’s green visor and into my snotty woollen author’s hat, the one covered in dirt from being thrown out the pram a lot, in about two seconds flat. As my own editor will tell you. But I love the shameless pride you get to take in seeing an author doing well. For a Scot, especially, it’s much better than that pride you might momentarily take in the success of your own books, which is of course a sin, and will often find its immediate punishment. No one believes me, but for us … someone paying you a compliment might as well be stabbing you in the chest.

CG: Last year, when I spoke with Griffin International Poetry Prize Winner, Michael Longley, he said at this point in your writing life you have “all the tools for producing forgery and it’s important not to.” What constitutes “forgery” for you?

DP: Professing to feel what you don’t. And deluding yourself you’re breaking new ground when you’re just digging up the old. As the Sufis say, when you finish the work, dismantle the workshop. Michael’s bang on. There are times when you have nothing to say, or at least nothing you haven't already said. I think you should take poetry seriously enough to not write it.

CG: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use?

DP: Derek Mahon once told me that for poets, “reading is the same as writing.” Just because you’re not covering the page doesn't mean you’re not making careful preparation. There’s no hurry for this stuff, no deadline to meet, so you might as well get it right.

CG: What’s next for Don Paterson?

DP: Oh god—ask the horse. Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise—in terms of stuff, I’ve a crazy long unreadable treatise on poetics out next year, which I barely understand. Then a New and Selected aphorisms, and a book of versions of lots of different European poets, mainly on ideas of the soul, in which I have very little faith but tend to obsess over anyway. A new long poem, which will take an age. A couple of very short introductory books, I think. A play. And I’m playing music again after a 12 year lay-off, which is proving to be fun, for me at least, so I have a bunch of gigs coming up with a quartet. Kids, dogs, lecturing, editing, Netflix, y’know—anything but actually having to face myself in silence, ho ho … I mean—if one were to live until the age of 250, treating your entire life as a displacement activity would be pretty unhealthy, but given where we are, it seems a reasonable use of the time. I’ve learned a lot from working with Clive James over the years: Clive projects himself into the future through his books, and these days it keeps him going where folk who’d asked less of themselves would have dropped. “Always giving yourself something to think about” might not be the life, but it seems to me a life.

DON PATERSON

40 Sonnets

Faber & Faber, 2015

| 40 Sonnets is the new collection by Don Paterson, a rich and accomplished work from one of the foremost poets writing in English today. This new collection from Don Paterson, his first since the Forward prize-winning Rain in 2009, is a series of forty sonnets. Some take a more traditional form, some are highly experimental, but what these poems share is a lyrical intelligence and musical gift that has been visible in his work since his first book of poems, Nil Nil, in 2009. In 40 Sonnets Paterson returns to some of his central themes - contradiction and strangeness, tension and transformation, the dream world, and the divided self - in some of the most powerful and formally assured poems he has written to date. |

RUSTY TALK WITH KRIS BERTIN

| Kris Bertin is a writer from Halifax, NS with work featured in The Walrus, The Malahat Review, The New Quarterly, PRISM international, and many others. He is a two-time winner of the Jack Hodgins' Founders' Award for Fiction, and has had his work anthologized in The Journey Prize Anthology, Oberon's Coming Attractions, and EXILE's CVC Anthology. His first book of short stories, entitled Bad Things Happen, was published by Biblioasis in 2016. Born into a military family, Kris lived in BC and Ontario as a child, then did the rest of his growing up in Lincoln, New Brunswick. He attended Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, studying English Literature and Creative Writing, but left before graduating. Since then, he has worked as a mover, a general labourer, an assistant curator in an art gallery, a call-centre cell-phone rep, a Mongolian-grill cook, a bouncer, and a writer. He currently works as a bartender at Bearly's House of Blues & Ribs. You can visit him at krisbertin.com. |

The book has criminals and drug addicts and heartache and a ten-foot tall god in green robes. It has garbage collector-hillbilly feuds and little girls breaking into houses. It tracks the journey of a window-cleaner who becomes a telemarketing fraudster in Montreal, then returns home to absolve himself by becoming an exterminator in rural PEI. I can talk about that all day long. But me, and my role in it is boring. It’s like if you had a machine that could see people’s dreams, but instead you just look at the poor sap quivering on the bed in his jammies.

Kris Bertin: Thanks for saying that. I wrote the stories in this book over a long period of time, so I think of each of them as being very different, but one tack a hasty reviewer can take is to simplify and categorize everything you’ve done. No one who puts together a collection is trying to write the same thing over and over; all of us try to vary it by tone and character, conflict, themes, and a bunch of other factors. So I feel like for most short story collections—and for this one—we’re working toward different goals. I want it to be a rainbow and a capsule reviewer wants to call it orange. It’s unavoidable.

But, to be specific, when someone says these stories are “dark” or “gritty” or about “outsiders,” they’re wrong. Some are about those things, sure, but they’re also about middle-class moms and falling in love and small towns and ghosts. Some are difficult, some are depressing, but they’re also playful, sometimes melancholy.

CE: There’s an intense level of description throughout the book that runs from people (“She did have a scar on her stomach, but it was going in the wrong direction.”) to settings (“My door is too wide for the doorway, but also too short.”) to smells (“...that pulpy hamster-cage odour that develops when no air circulates.”). Does this kind of observation come naturally to you, or is it something you’ve had to cultivate? At what point in your writing process does description come in?

KB: When I describe something, it’s usually just a manifestation of what’s particularly vivid to me during the act of imagination. Some pieces pass by, unimportant, but sometimes there’s an element that, if made real by an image, will convey something to the audience that I can’t otherwise communicate. I feel like there’s no reason to slow things down unless you have something to show, so I’m content to use short sentences and ordinary description up until there’s something I want to share, something vivid or challenging, or something I’ve seen in real life that I can’t get out of my head.

As for its origins, I guess it’s something that comes naturally. I don’t know many writers who aren’t astute observers, so it’s probably part of the package for most of us. Paying attention counts, always, but it counts double if you’re the kind of weird person who walks around, trying to save up enough thoughts and ideas throughout the day so that they can arrange them in a little word mosaic when you finally get home.

CE: One review of Bad Things Happen on Goodreads states that “there was nothing to really RELATE to, as it was a level of wallowing and belly crawling reserved for thee sheer garbage of society,” which I found interesting and a bit funny, if inaccurate—the book is actually quite relatable. Does it matter to you how your work is read? Do you even care if readers find your characters relatable?

KB: Goodreads reviews are a laff riot, and that is definitely a good one. Goodreads was created for people to promote and share their love of books, but has instead morphed into a weird literary Youtube comments section. Me, Kevin Hardcastle, and Andrew Sullivan all got attacked by the same person (a troll who didn’t write reviews for any other books, except for ours), saying that we were “offensive.” I love that review. It’s a badge of honour to me:

Even more offensive characters. Title makes me think this is young adult literature.

Author's bio, if it's real, is hilarious. The Great Gatsby himself is now writing fiction.

Do I want the work to be relatable? Yes, absolutely. I want to make accessible work that doesn’t presuppose a certain level of education, or experience. I want characters who, even if you can’t imagine being them or in their situation, you can understand their motivations and actions, and how it might feel to be them. But do I worry about being misread? Not really. I can’t worry about this stuff. The vast wasteland of self-obsessed, childish and insane Goodreads contributors is a great example of why I shouldn’t.

CE: Work is a recurring theme throughout the collection, from service industry to petty criminality, with many characters barely maintaining or on the cusp of losing jobs they don’t particularly enjoy. If you weren’t, like the rest of us, financially dependent on working, would you still work anyway?

KB: Well, writing is work, and I don’t plan on ever stopping that, so yes. But if you’re asking whether I’d continue doing a different job as well, the answer is probably yes. If money was no longer a concern, I think I’d like to do community work—volunteer a men’s shelter (likely the one where a lot of my customers come from), or something like that. I would do that now, if I had more time, and routinely feel shitty about myself for not helping out in that way.

I will say, though, that I really do love bartending. I love when it’s dead and I get to talk with and meet different people, and when it’s not, I love the pressure of being busy and trying to do everything perfectly, trying to solve five problems at once. I love being behind the bar, making drinks, taking care of people, making sure they’re safe and no one’s bothering them. I’m not convinced it’s something I would ever be able to fully leave behind. Throughout the years my home bar has gotten bigger and bigger and now I’m at the point where I’m always ready for a spontaneous forty-person party (which has never happened).

CE: You’ve been posting some older stories—ones that didn’t appear in Bad Things Happen—on your website for free, with write-ups about where they came from and why they didn’t make the cut. When you look at your older work, what do you see? What has changed in your writing between then and now?

KB: I think the stories I put on the website are good ones. The truly terrible, unreadable stuff will never be shared, but the ones I put up are so old that I don’t have any bad feelings about them whatsoever. I find if you’ve put something aside, it’s easy to hate it while it’s relatively fresh, but as it ages, it solidifies. It’s no longer malleable, and your feelings about how to fix it, or what ought to have happened vanish. You’re not thinking about the same things, or in the same way anymore. So it just becomes inert. A story you couldn’t write now, because your concerns are different, your life is different. The materials are out of stock, the methodology lost. I don’t know how I would go about making another “Boardwalk at Midnight” or “Gorilla Painting.”

What I see in those stories is a lot of uncertainty about the future, a lot of anxiety about love and career, a preoccupation with—what I think the back of the book says—“who we are, and what we want to be.” I think that last part will always be what I’m interested in, but the big difference with what I’ve been doing lately is that I’ve moved away from smaller, more personal stories, and tried to branch out into the more complicated and even stranger world of everybody else. The story “The Narrow Passage”—about peering into the naked lives of people by what they leave behind (in the trash)—was my newest story in the Bad Things Happen, and the one that most embodies these ideas.

CE: You’ve been working on a couple of novels and some much longer short stories. How does the process of writing long prose differ from writing short prose?

KB: This is obvious, I’m sure, but it takes a lot longer to do a big one than a little one. The form is different but the process isn’t really. I think, in some ways, longer stories can be trickier, because they make you think you have room that you probably don’t. It’s easy to think you’re taking time to explore something when really, you’re just meandering. So in writing a 10,000–15,000 word story, there’s a lot more editing, a lot more drafts, a lot more ghost passages floating around, unsure of their place until the very end when it all comes together.

CE: You’ve had a successful few years, with over a dozen stories appearing in journals and anthologies, and now a well-received collection under your belt. At what point in your career, if at all, did you become comfortable describing your self as a writer?

KB: I am a writer, but it’s not something I’d ever bring up at work. Even the copies of my book I have behind the bar are for people in the know who ask about it. I’ll identify as a writer when I’m in the right place, but otherwise I think going around talking about it is weird. Why would you do that unless you want attention for it? I don’t. I think focusing on the author is a mistake, too. Who we are isn’t interesting, what we make is.

The book has criminals and drug addicts and heartache and a ten-foot tall god in green robes. It has garbage collector-hillbilly feuds and little girls breaking into houses. It tracks the journey of a window-cleaner who becomes a telemarketing fraudster in Montreal, then returns home to absolve himself by becoming an exterminator in rural PEI. I can talk about that all day long. But me, and my role in it is boring. It’s like if you had a machine that could see people’s dreams, but instead you just look at the poor sap quivering on the bed in his jammies.

Wow, look, he’s really sweaty. Look at his eyelids. His hands keep opening and closing.

Turn on the Dream-O-Tron, for God’s sake! Let’s have a look in there!

KRIS BERTIN

Bad Things Happen

Biblioasis, 2016

| Description from the publisher: The characters in Bad Things Happen—professors, janitors, webcam models, small-time criminals—are between things. Between jobs and marriages, states of sobriety, joy and anguish; between who they are and who they want to be. Kris Bertin’s unforgettable debut introduces us to people at the tenuous moment before everything in their lives change, for better or worse. |

RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL PRIOR

| Michael Prior's poems have appeared in numerous publications across North America and the UK. A past winner of The Walrus's Poetry Prize, Matrix Magazine’s Lit Pop Award, and Grain’s Short Grain Contest, Michael is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Cornell University. Model Disciple (Véhicule Press, 2016) is his first full-length collection of poems. |

"I think distraction is in a way essential to my poetics."

Michael Prior: It’s interesting, because we talk about how relating a dream to someone is one of the most boring things in the world: no one wants to hear someone else’s dream. But in a way I feel like poems often are our own dreams, though we’ve done something that’s made them palatable for an audience.

Perhaps what you’re picking up on is that I often embed the narrative in different ways. For the most part, I’m not interested in writing strictly narrative poetry, and part of that means subordinating any kind of narrative sense to an associative sense.

JN: Regarding that “associative sense”: It also struck me that many of your poems are about incredibly personal and in some ways very urgent subjects, but at the same time you seem totally willing to deviate from this urgency—for example, by refocusing attention on a beautiful image or even just a poetic sound pattern. I think of these almost as ornate aspects of the poems. What draws you to the ornate, or what leads you to focus attention on these kinds of images?

MP: I would hope that most of these images or lines are reframing the poem in some way. Because these poems are often about deeply personal and often deeply political things, historical things, with a perspective on trauma, and loss, and the deprivation of citizenship.

If I were just to write exactly what I mean, to follow a more argumentative or direct logic—though there’s lots of great poetry doing that—it wouldn’t be true to my experience, which is one of confusion and constant distraction. I think distraction is in a way essential to my poetics. Maybe it comes back to the dream thing: dreams are full of distractions and the inability to get where you’re actually going. I’ve never had a dream where I’ve accomplished anything I wanted to accomplish in that dream. Most of my poems, if they do have ornate moments—I don’t know if that’s exactly the word I’d use—or if they do have consciously poetic moments, it’s because their inclusion somehow rings more true to me. I don’t think my experience of the world has been so linear, so teleological, so politically straightforward.

It’s often the same with the poets I’m interested in, too. If you look at the work of Bishop, Lowell, a lot of mid-century people like that, or even later poets like Merrill and Gunn, the ornate can be very political. The ornate can say something by re-framing an idea, or by subverting a set of semantic expectations through the reflexivity of form. I hope that these moments you’re talking about were surprising; if they weren’t, then perhaps I didn’t accomplish what I was aiming for.

JN: Surprise is definitely a big part of it. I think what’s often happening when I read your poems is that there’s a strong narrative I can start to pick up on, but then I’m surprised by how it comes through in these images. They can seem unrelated at first, but they quickly become a striking and integral part of the experience.