RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL LONGLEY Michael Longley Michael LongleyPhoto credit: Kelvin Boyes Michael Longley was born in Belfast in 1939. He has published nine collections of poetry including Gorse Fires (1991) which won the Whitbread Poetry Award, and The Weather in Japan (2000) which won the Hawthornden Prize, the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Irish Times Poetry Prize. In 2001 he received the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry and in 2003 the Wilfred Owen Award. He was awarded a CBE in 2010 and was Ireland Professor of Poetry, 2007-2010. Catherine Graham: Congratulations on winning the Griffin International Poetry Prize for your tenth collection, The Stairwell (Cape Poetry). Like a stairwell, this book contains poems of passages—birth and death, childhood and old age, conflict and peace. During your acceptance speech you mentioned that you’ve been writing since you were 15. Was there a moment when you realized you were a poet or was it something that just built up over time? Michael Longley: It built up over time. I feel very superstitious about calling myself a poet. It’s what I most want to be. CG: The Stairwell consists of twenty-three elegies for your twin brother, Peter. Homer’s Iliad also permeates the collection. I wondered if you could talk more about how this book came into being. ML: I was with Peter when he died. At the time I wondered if I would ever be able to write an elegy for him. I ended up writing twenty-three. I gathered them into the second half of the book as a sustained lamentation. As so often in the past Homer came to my rescue and helped me to find the words. In some of the poems in the first section I celebrate grandchildren, and that lightens the elegiac tone a bit. Arrivals and departures. CG: When you were a student at Trinity your first poem “Marsh Marigolds” was published in a literary magazine called Icarus: She gave him marigolds The first three lines are weaved into “Marigolds, 1960” uniting the young poet you were with the experienced poet you became. It’s one of my favourites in The Stairwell. Can you tell us more about this poem and/or the process behind it? ML: The poem was published in the Trinity College literary magazine Icarus at Easter 1960. Although I didn’t realise it at the time, my father was dying. He discovered the poem and told me it wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. He was right of course, but he shouldn’t have said that. In ‘Marigolds 1960’ I forgive him his frankness, but much more importantly I grieve for him and suggest that at the end we were drawing closer together. It pleases me that my juvenile verse helped me in my seventies to frame an elegy for my father. CG: You have said at this point in your writing life you have “all the tools for producing forgery and it’s important not to.” What constitutes forgery for you? ML: Faking emotions. Imitating yourself. Pretending you have something to say when you haven’t. Passing off five-finger exercises as true art. Silence is infinitely preferable to such shams. Indeed, silence is part of the enterprise. CG: Who were some of your early influences? ML: Walter de la Mare, Keats, e.e. cummings, Louis MacNeice, Auden, Yeats, Wilfred Owen, Edward Thomas, Hart Crane, Dylan Thomas, Richard Wilbur, D.H. Lawrence, Theodore Roethke. I was quite promiscuous. CG: What are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen in the world of poetry since you started? ML: The word processor and the way it encourages you to mistake garbage for the real thing. The Creative Writing industry and the retreat of poetry into academe. A good poem is just as rare an event as it always has been. CG: Can you share some of the highlights of your Griffin experience? ML: Meeting my fellow poets and sharing with them the nervy excitement of it all. Being charmed and impressed by Scott Griffin and reassured by his marvellous staff. Not expecting to win and then winning. Phoning my wife in Belfast to give her the good news. The bigheartedness of the whole enterprise. The vision and the details. CG: What’s next for Michael Longley? ML: I have written about half a new collection of poems. I am also putting together a selection of my prose – essays, lectures, introductions, articles, reviews. And I am working on a memoir – before I forget everything . . . MICHAEL LONGLEY'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

"Dementia became a metaphor; I began to see the time we’re living in through a lens of dementia." |

Jane Munro: That’s a good question. I remember feeling it was hard to justify spending time on poetry—instead of doing something obviously useful—when there was no external evidence that I was a poet.

As a young mother with three children, I'd go so far as to ask myself, if I weren't me but a young male poet deciding whether to hire a babysitter so he could work on poetry or save his money and spend time with his kids, or some other such choice I found difficult, would I know what to do?

I’d know. It wasn’t always the same answer, but when I called myself a poet and took being a woman out of the equation, I’d know what it was best to do.

Even after I’d published books, being a poet felt different from being someone who composed poetry. I juggled writing time with time for family, earning a living, studying. Did real poets live the kind of life I was living?

At some point, I stopped worrying about whether or not I was a poet.

Perhaps the turning point came when I figured out that my best contribution to the welfare of the whole was to be myself – liver cells didn’t help the body by trying to be bone cells (not that they had such a choice) – and that being oneself wasn’t “selfish” (my mother’s accusation about artists). It also helped to grasp that even DNA is flaky: mathematicians could devise a stronger code.

CG: The first of four sections, “Darkling,” is a sequence of poems numbered one to twelve that seems to counteract a husband’s descent into Alzheimer’s by celebrating the physicality of life with its vivid, precise and sensual imagery: “the glans of a penis, smooth as an acorn,” “The stone that made me think of a full soul / smooth and heavy in my hand,” “A candle guttering.” In the second Darkling, the defiant line “Peeling the grape of death” appears. Your poems are like peeled grapes, more flesh is revealed as one reads them through. Can you tell us about the origin and development of this book?

JM: In a crisis, sealing off vulnerable parts may allow you to do what’s essential. But when it’s not exactly a crisis, even though your reality is a slowly aggregating disaster (such as dementia or what’s happening with climate change), locking yourself into coping mode (being hide-bound) isn’t synonymous with self-protection. But it’s easy to get trapped in the pain of grief.

When I started writing the poems in Blue Sonoma, I had classic responses to pain: anger, self-pity, helplessness, hopelessness. I was even afraid my own life was over.

Making art took heart, mind, body and spirit. Working on the poems made me feel whole. There wasn’t any choice about vulnerability. Peeling the grape of death meant more flesh was revealed.

Dementia became a metaphor; I began to see the time we’re living in through a lens of dementia. If the poems were to provide architecture for the imagination of others, they had to be inhabitable. I didn’t think of them as mine though they came through me and drew on my resources. That’s why I like doing readings: it’s my chance to sense the poem complete its transitive arc; feel others move into it, furnish it with personal stuff.

I don’t know if this answers your question. I wasn’t in any rush to finish the book.

CG: It does answer my question, thanks. In the section “Dream Poems,” dream-reality is reproduced through stark and stirring imagery. These poems are often laced with a post-dream realization such as the last line from “The net of heaven is cast wide”: “He is not a person I knew in life.” Could you tell us more about your relationship with poetry and dreams?

JM: In the iceberg of consciousness, the vaster realm floats beneath the surface of day-to-day thought. Sometimes, I feel that we all share an unconscious reservoir of imagery and story.

While I was writing Blue Sonoma, I was recording dreams. This kept me in a conversation with images from the less-conscious parts of my mind. If I’m right that we share some of this material, then dream imagery might also connect with deeper layers of the reader’s consciousness.

Not every dream comes from that level; some appear to simply recycle a day’s debris. The poems in the second section of the book are records—translations—of specific dreams. Many of the other poems in Blue Sonoma draw on dream imagery, or move as dreams move. Each of them was a mystery. During its gestation, I’d be curious to meet it. For some, that took a long time.

CG: The spare and moving 11-part sequence “Old Man Vacanas” is cutting in its frankness and dark with black humour. The consistency of the voice addressing or observing “the old man’s” struggle with dementia links the poems into a cohesive monologue. How did this section come together for you?

JM: The “Old Man Vacanas” are contemporary approximations of an ancient poetic tradition. In Kannada, a South Indian language, vacana means “saying; thing said.” Vacanas are colloquial prayer poems using natural and domestic imagery to voice—often, complain about—family, village, spiritual, and philosophical issues. Unlike poetry in Sanskrit, they aren’t aureate.

The 12th Century vacanas were prayers addressed to Shiva—or, more precisely, to the poet’s personal deity (Mahadeviyakka calls on “my lord white as jasmine”). In “Old Man Vacanas” the “you” is not identified. I thought of the “you” as the listener.

The poems in this sequence started coming during a snowstorm when we were cut off—the roads impassable. I wrote one after another. This doesn’t happen for me very often, not with that intensity: every time I sat down, another came. I liked them and kept them. Later, others came. I couldn’t tell how long the run would be so played around with it over the next five or six years. Eventually, “Old Man Vacanas” came down to the set of eleven in Blue Sonoma. It was an odd number.

CG: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use?

JM: Write as if you’re already dead. This advice is attributed to Nadine Gordimer, but it reminds me of Krishna’s injunction to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita: surrender the fruits of your actions.

Yogis say we have the pleasure of doing our work but no control over its outcomes. That’s the thinking behind Karma Yoga (karma means action).

Yoga practices end with Savasana—corpse pose—during which you let go everywhere, release what you did or didn’t do, drop body and mind into stillness and silence. It’s refreshing and energizing.

CG: What were some of the highlights from your Griffin experience?

JM: Oh, my! It was all extraordinary: reading to over 1000 people—Koerner Hall filled with poetry and their attention; meeting and listening to the other shortlisted poets; the generosity and sincerity of the Griffins: their love for poetry, their vision, their attention to every detail; meeting the illustrious Griffin Trustees and jurors, many of whom I hadn't met before; the recitation by Ayo Akinfenwa (finalist in Poetry in Voice) at the gala; the way everything left me feeling hope for poetry. And, of course, winning: my daughters and friends with me—even distant friends and family watching. A Griffin has wings. I was transported.

CG: What advice would you give to an aspiring poet?

JM: Read and write, read and write, then read some more. Relax; be present; be curious; pay close attention; be patient.

CG: What’s next for Jane Munro?

JM: Writing: settling into my own rhythms and practices and work. That’s the main thing. This fall, thanks to an apartment exchange, I’ll spend a month in Germany. I was in India for two months last fall studying yoga. It’s ages since I had much time in Europe.

=

= Jane Munro

Brick Books, 2014

Winner of the 2015 Griffin Poetry Prize

A wise and embodied collection of dreamscapes,

sutras and prayer poems from a writer at her peak

In Blue Sonoma, award-winning poet Jane Munro draws on her well-honed talents to address what Eliot called “the gifts reserved for age.” A beloved partner’s crossing into Alzheimer’s is at the heart of this book, and his “battered blue Sonoma” is an evocation of numerous other crossings: between empirical reportage and meditative apprehension, dreaming and wakefulness, Eastern and Western poetic traditions. Rich in both pathos and sharp shards of insight, Munro’s wisdom here is deeply embedded, shot through with moments of wit and candour. In the tradition of Taoist poets like Wang Wei and Po-Chu-i, her sixth and best book opens a wide poetic space, and renders difficult conditions with the lightest of touches.

Grey wood twisted tight

within the framework of the tree –

impossible to snap off,

forged as it dries.

And in me, parts I can’t imagine

myself without – silvering.

~from “The live arbutus carries dead branches…”

Praise for Jane Munro:

“spellbinding … haunting … thoughtful, evocative … arresting images … Zen-like spirituality… ” ~The Toronto Star

Excerpt from Blue Sonoma, Brick Books 2014

In a small boat off Port Renfrew

caught the moon.

It was pale and pocked.

It lengthened from disc to oval to flat fish

as she lifted it. The rod bowed.

When the rod’s tip touched the water’s surface

the moon sprang from the wavesstreaming foam, and soared overhead.

The woman fell on her back –

winded, wordless – rocking as the boat rocked.

The moon hung above her

huge and closer than a star.

It had grown on a tongue of silt

at the river’s mouth, dark-side-down

resting on its mind-reading side,

then slid to deep waters.

Staring up at it, the woman knew it knew.

RUSTY TALK WITH RUSSELL THORNTON

Russell Thornton

Russell ThorntonCatherine Graham: Congratulations on your Griffin Canadian Poetry nomination for your collection, The Hundred Lives (Quattro Books). Was there a moment when you realized you were a poet or was it something that just built up over time?

Russell Thornton: I don’t think much about being a poet, to be honest. I do think a fair bit about writing poems. I’ve always scribbled poems—since I was around 9 or 10 anyway. Before that I often made up rhymes and poems and kept them in my head. I started saving poems I’d written when I was 19-20. I guess that very late teenaged period was a threshold in a long build-up. From my early twenties on, I knew that I wanted to try to write a decent poem. In fits and starts and with many detours, producing poems has been important to me since that time.

CG: The first section of The Hundred Lives, "With a Greek Pen," takes us to Greece. Did you go there specifically to write? Tell us about your relationship with place.

RT: I went to Greece because I interviewed in Vancouver for a job in Greece and got the job. I’ve never gone anywhere other than a kitchen table or a corner of an apartment to write—except for the last few years when I’ve sat in the local public library for an hour or so a day five days a week (if I’m lucky). Banff, Sage Hill, Spain, Scotland, Iceland, Vermont—I wish! Who knows? Maybe one day.

I’m aware that to say that place in the traditional sense is important in poetry is more than a little out of literary fashion at the moment. Our “place” is social media, electronic culture, and the global urban reality. I’m not averse to what the new “place” might help produce in poetry—but place in an older sense is more significant to me. Do you know that wonderful poem by Wallace Stevens, "Anecdote of Men by the Thousand"? A couple of the stanzas have always hit me as being very true:

There are men of a province

Who are that province.

There are men of a valley

Who are that valley.

There are men whose words

Are as natural sounds

Of their places

As the cackle of toucans

In the place of toucans.

The dress of a woman of Lhassa,

In its place,

Is an invisible element of that place

Made visible.

But of course Greece affected and continues to affect me. I lived in Larissa and Thessaloniki for a few years—coming back to Vancouver a couple of times to drive taxi for a while. I’ve returned to Greece several times over the past decade. I’m struck again and again by the power of the place—that hypnotic white light, that eerie ubiquitous rock, that sea. In terms of the people and culture of the place, there is that deeply wild music, and there is that set of gestures; that excitation and sense of vastness coming always into strict specificity and form. I might have based myself permanently in Thessaloniki or Athens if the person I met in Larissa and became engaged to hadn’t died a very early death from cancer. In the section of poems in this book of mine that you mention, “With a Greek Pen”, she is the person other than me in many of the poems.

CG: The poems in the second section, "Lazarus’ Songs to Mary Magdalene,” are responses to the Gospel story of Lazarus and are sonnet-like in shape. Is there more to tell us about your use of the sonnet or form in general?

RT: I’ve always loved form in poems. After all, most of the great poems of the English language employ significant aspects of form! Shakespeare’s sonnets are the obvious example. When I first began getting poems in magazines, I knew my poems looked a little more formal than most of the things I saw around, especially in west coast publications. I was using quatrains, counting syllables, and so on. Around the same time, of course, “formalism” was beginning to display force in Canada. But I’ve never been interested in form for form’s sake, or for trying to show off, or for trying to gain false authority. A lot of contemporary formal poetry reminds me of paint-by-number artwork. It’s unnatural, laboured, and empty. I’ve always been attracted to authentic heightened natural speech. I think adept use of form can help with that—but certainly not always. At the very least, poetic form can serve as somewhere to hang one’s hat, so to speak. It can aid in the control that is a basic principle in poetry. In my own case, I’ve been profoundly affected by my discovering that emotion can usher me into form without my initially dictating that form. It’s a humbling experience. Do you know that incredible poem by Emily Dickinson? The first line is “After great pain, a formal feeling comes—”. The emotion is foremost. There’s that Ezra Pound pronouncement: “Only emotion endures.” If you happen to start with form, and emotion, thought, and imaginative energy don’t take over pretty quickly, form is nothing.

As for these particular sonnets of mine, my hope is that the sonnet form helped me with the control of emotion and the dramatic organization. These pieces are meant to be “little love songs” in the traditional sense of the sonnet. But they’re only very loose or rough sonnets. They’re fourteen lines long, the lines are usually ten syllables long, and they have “turns”—but that’s it. No rhyme scheme. No formula for stresses within the lines. And so on. The loose form flowed naturally out of the material of the poems.

CG: What was it like for you reading at Koerner Hall the night of the Griffin shortlist readings?

RT: Well, I didn’t piss my pants. And I didn’t forget my name or how to speak English. It was an exciting literary ride, let me tell you. Do you know of a talk that Sharon Olds gave once about a big award experience? It’s on some video that I once took out of the Vancouver Public Library. She says that she felt as if she was standing at a stage on the audience side, on tiptoe, holding herself at the edge of the stage with her fingers and looking across the stage, her eyes just high enough to see the shoes of the poets who were about to read their poems.

That’s how I felt reading at Koerner Hall. I had to keep reminding myself that I was actually one of the readers.

My best little memory is this, in two parts: Michael Longley and I sat together for a few moments in the Koerner Hall “green room”. He saw me gobbling my Halls. “Are those sweets?” he asked me. “Could I have one?” He mumbled something about “sugar level”. I gave him a couple of Halls. Later, at the after-reading gathering, I found him in a lull. I told him that I carried several of his poems permanently in my head, just wanted to tell him, and how nice it was to meet him. I said the first line of his poem “Swans Mating”. I think maybe I was going to say the whole poem. Anyhow, he took it from there and quietly and lyrically recited the whole poem by heart to me. On the spot, in a little humble, holy space in the midst of the noise.

CG: Who were some of your early influences?

RT: My very earliest influence was my maternal grandmother—who published hundreds of stories under various pseudonyms in what were once called “women’s magazines”; she was a talented storyteller. She was actually more truly a writer of poems, though little published except in newspapers when she was a teenager (there were few opportunities for magazine or book publication in her day; she wouldn’t have known about them anyway). She had a gift for metaphor and a wonderful ear. My other early influence was Irving Layton. I met him in Montreal when I was 19, took a course with him, and in the years after that we became friends. Like a lot of people, I came under his spell. His personality and the power of his poetry held me. I continue to be swayed by his several masterpieces—the rhythms, the verbal texture and colour, the full, radiant passion in the utterance.

CG: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use?

RT: "A great poem is a noble work, and no one ever wrote one who didn't want to get out of hell."—Irving Layton

CG: What advice would you give to an aspiring poet?

RT: Read, read, read. Write, write, write. It’s the advice I give to myself.

CG: What’s next for Russell Thornton?

RT: For the past year or two I’ve been working on a manuscript that I’m tentatively calling The Terrible Appearances. What’s next is stealing daily time to try to transform my scribblings into finished pieces.

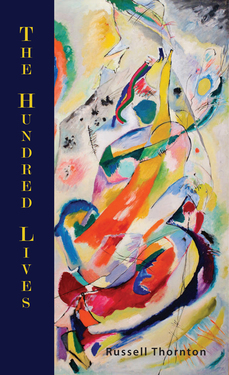

RUSSELL THORNTON'S MOST RECENT BOOK

THE HUNDRED LIVES

QUATTRO BOOKS, 2014

In The Hundred Lives Russell Thornton illuminates the intricate imaginative orders of love at work within an individual life.

From poems set in the eastern Mediterranean, with its abiding reverberations of the ancient Greek world, and informed by sacred sites and classical stories, to a series of sonnet responses to the Gospel story of Lazarus, to a lyric-narrative engagement with the mythic-erotic drama of the Biblical Song of Songs, to intensely personal poems that explore love and loss, this collection highlights the mystery of the interplay between inner and outer energies at the core of human experience.

THE CHERRY LAUREL

chewed cherry laurel leaves. When the poison

took hold and ushered them into frenzy,

they would see the vale was a hovering

of matter, a glittering haze. The earth

their bare feet danced on, and that had brought forth

everything around them, would, if they

threw off the names they had used for themselves,

begin to reveal to them what there was

of eternity in the world.

The vale

could open into a being, human,

yet other, whose name was a limitless,

pure embrace in an instant with no end;

then could close again and be a chaos

of innumerable identities

interspersed with abyss upon abyss.

It could pour blind currents of life, of death,

through the women’s living skulls, and plunge them

into metamorphoses—so they might

suddenly know more than any mortal,

having become the vale itself, knowing.

Some would never return from such knowing,

and collapse and die. But others would now

be called Daphne, the name for the laurel,

and be priestesses.

The light of the vale

is in love with those frenzied ones—the rays

sent as from Apollo still following

the woman who ran from him and escaped

when she was changed into a tree. The fate

of even Apollo’s love is held here

in the laurel branches. Here, your own fate,

though you do not know that fate, pours through you,

while the light, the vegetation, and rock,

so bright, so mysteriously exact,

are a moving stillness about to speak.

Vale of Tempe

RUSTY TALK WITH MIKE WATT

Mike Watt

Mike WattPhoto Credit: Carl Johnson

Mike Watt played bass in Minutemen, and for that his place in musical history is assured. However, Watt is not a man to rest on his laurels. When he turned 57 in December of last year, he'd recently completed a 51-shows-in-51-days US tour with his band Il Sogno Del Marinaio (his two Italian bandmates are in their 30s). Earlier in 2014, he toured Europe with one of his other bands, Mike Watt + The Missingmen, and after a flurry of US shows at the beginning of this year he is now back in Europe with the Missingmen, this time touring his third “punk opera”, Hyphenated-Man. He’s released 5 albums in the last 4 years on his own clenchedwrench label. He hosts a radio show and podcast called “The Watt from Pedro Show”. He publishes extensive tour diaries on his website, a rich self-archive he calls hootpage. He also makes albums and tours the world with the Stooges, for whom he has played bass since Iggy Pop reformed the group in 2003. So if you wanted to call Mike Watt the hardest-working man in punk rock, there would much to back that up. It’s a title Watt himself, with his stubborn prole modesty, would probably take some pride in. However, to do the man justice you’d have to expand on the terms employed.

Watt doesn’t just work the bass back and forth from stage to studio, he also works up and down, plumbing depths and scaling heights. While musicians reared on Minutemen are already embarking on reunion tours, Watt remains restless and forward-looking, constantly challenging himself with a range of new projects. All this to say that hard work, for Watt, doesn’t simply mean pounding the pavement and honing his craft—it also has something to do with artistic renewal and growth.

Then there’s the question of what is meant by punk rock. Minutemen were founded in 1980 by Watt and his childhood friend, guitarist D. Boon, in their hometown of San Pedro, California (drummer George Hurley completed the trio). While the band was among the pioneers of the West Coast punk scene, their distortion-free sound was never exactly what most people thought of as punk music. Minutemen’s brilliant run came to a sudden, tragic end in 1985 with D. Boon’s death in a car accident. Watt’s subsequent output in bands like fIREHOSE, Dos, and others has veered even farther from the strict genre of punk, but as Watt points out, for him and D. Boon punk was an idea more than a musical style; it was an ethos, a politic, a practical philosophy, a movement. Few bands put this idea to such inspired use as Minutemen, and fewer people have remained as fiercely, and productively, committed to it as Watt.

My excuse for proposing an interview was that I had recently read and admired Watt’s 2012 book Mike Watt: On and Off Bass. It pairs his handsome digital photographs of San Pedro with excerpts taken from his tour diaries, which are written in searching chunks of rhythmic, Beat-like poetry-prose.

the band’s making quite a sound but there’s another aspect that’s much impressed upon me also – this energy electricity-sounding-like-fabric-ripping thing that’s put a big awareness on me … prying my pie-eyed eyeholes even wider to push this scene inward to pull my mind more outward. (july 23, 2005 – carhaix, france) |

As we were wrapping up, I asked him what he’d been reading lately and he proceeded to rattle off a diverse list followed by characteristically to-the-point capsule reviews. Some of the books included a collection of interviews with Ivan Illich (“Interesting cat”); 1776 by David McCullough ("I was thinking this is a book that somebody would give D Boon. That’s why I read it … but it was kind of lame.”); Beatrice & Virgil by Yann Martel (“It ain’t about fucking Dante I’ll tell you that.”); The Master and Marguerita by Mikhail Bukakov (“That is a very good book. I really liked it.”); The Pillowbook by Makura no Sōshi (“Yeah, it’s basically something like aesthetics – here’s what I like, here’s what I don’t like. Really trippy.”); and books about Stalin and Mao ("Fuck, talk about trudges … 800 pages each.")

A conversation with Mike Watt is a history lesson in the best sense. He is aware of how rich his past is, and he’s given it much thought so he is happy to talk about it – sometimes fondly, sometimes not, though he never sounds nostalgic or bitter. Speaking in the same singular vernacular that features in his writing, he is blunt and self-deprecating and enthuses easily. His energetic mind roves happily and rapidly, embarking on top-of-the-head riffs that can initially seem like unrelated tangents but eventually reveal themselves to be variations on the themes he is always circling: writers and artists; punk rock and D. Boon; peddling, paddling, and Pedro.

Our conversation took place via Skype last in December and has been edited and condensed.

MICHAEL VASS: How did your book On and Off Bass come about?

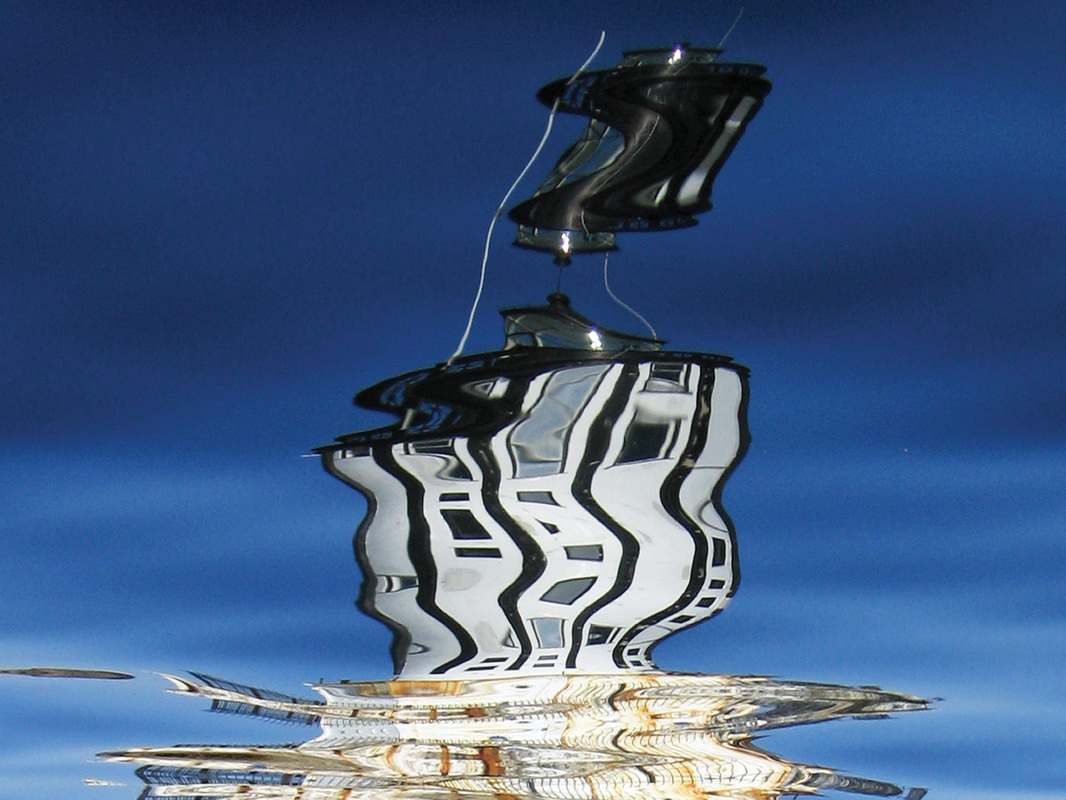

MIKE WATT: It comes from an art show I had in Santa Monica a couple years ago at Track 16 Gallery … Well, let me start at the beginning. In the ‘90s, Columbia, the label, gave me a [digital] camera to bring on tour. Using one of these cameras, you don’t have to buy film. You can take chances and if the shot is lame you just delete it. This was just a whole other sensibility. I’d had a photography class in, I think, the 10th grade, that’s the only kind of picture-taking experience I had. So I came back from tour with this camera, and around the same time I started riding a bicycle again after 22 years. I don’t know if you know where San Pedro is, but it’s a harbour of Los Angeles, so we’re trippy for So Cal. We’re very much a working harbour.

MV: Not a beach town.

MW: No, not really. But it does have nature. It has these cliffs, the end of the land is here, mixed in with these docks and hammerheads and cans and big boats. So I started taking pictures with this camera. And then, about four or five years of that and my knees were killing me, so I started doing kayak. Point is, when I’m not on tour and I’m in my Pedro-Town, I’m up at the crack of dawn, in a sound kind of mind. I’m trying to capture it with pictures. I’d float these [pictures] around to my buddies on my email list. Laurie Steelink said, "Oh, we should print some of these.” I said, "Like which ones? Here I’ll give you a bunch and you just pick." So she picked these out and put them on the wall of this gallery, Track 16, and people came … It was a trip, I’d never done anything like that. A couple people at the show were Kat and Peter from Three Room Press in New York City. They were thinking, "Hey Watt why don’t you put this in a book? You do this diary when you’re on tour. So we’ll juxtapose diary entries when you’re out of Pedro against pictures with you in Pedro." I said, "OK, you go up on hootpage, you see all my diaries, you take the excerpts you want." So both situations, pictures and the spiels … I mean I did ‘em all, but I didn’t really pick them. So in a way, it’s kind of curated, or edited.

MV: So you put all your tour diaries online?

MW: Yeah. To me in this day and age, I don’t know what you guys think, because there is something about a book … But you put it on the internet and in a way you’re publishing it too.

MV: Yeah, of course.

MW: OK, you agree then?

MV: Well, The Rusty Toque is an online journal.

MW: Ah OK, so none of it’s hard copy? See that’s the way … People were telling me, "Man, you should print up these diaries!" I said, "They’re already published when you put them up on the fucking internet, people!"

MV: Did they run their decisions by you, about which photos and diary entries they chose?

MW: Maybe I had some little opinions about things. But I wanted some kind of objectivity, because I’m too close to this shit. I didn’t take those pictures or write those diaries to become a book or an art show. So I felt I didn’t have enough perspective. You know, I was new to this kind of field, so I didn’t have the confidence. I didn’t want to come off as so self-important, like I knew exactly what people wanted to know about me. Actually, you know, it’s my second book.

MV: There was a book printed of your Minutemen lyrics, right? [Spiels of a/ d’un Minuteman, published by L'Oie de Cravan]

MW: Yeah, the words I wrote for the Minutemen. In fact, that’s from your parts, Canada.

MV: From Montreal …

MW: That’s right. A little publishing company that puts out poetry. They did a translation, every other page is the Quebecois. The Minutemen were using a lot of slang ourselves, so I thought that was neat. We all get kind of provincial in our talking, our slang. At the same time language is for communicating, you know? By reading those words you might get a sense of what it was like to be in a band with D. Boon and George Hurley. That was my idea with that. I even put my first tour diary in there. I wrote one because it was the first time the Minutemen went to Europe with Black Flag. Man, I was really bad at it. Actually, diary writing – there’s kind of a technique to it.

MV: How did the diaries start for you?

MW: I do it on tours for a couple of reasons. One is just to keep it together, keep focus. Another one, I am writing for younger people—not to be their eyeballs, but to inspire them to get first hand experience. This idiot old guy in Pedro, driving around and working bass—if he can do it, you can do it too. The reason that I’m into that is I still consider myself part of the movement. And I owe the movement. The movement was so loose and autonomous, they let people like me and D. Boon living here in Pedro put on a gig. And Greg Ginn at SST – we were SST 002, the second SST record. That was an incredible opportunity that the movement gave us. I feel a debt. Since I was allowed to let my freak flag fly, I wanna turn people on to the same kind of trip.

MV: So going back to the diary writing – how has it changed for you? What are the techniques you learned?

MW: Well, the biggest enemy of diary writing is memory loss. Especially when you tour the way I tour, because I play every day. So you’ve gotta do it the next day. If you get behind, everything blends into the same fucking thing. Each day is unique. I mean, you can get all reductionist, you know: woke up, took shit, took piss, ate chow, drove to gig, did gig, conked … repeat. You don’t wanna do that. You wanna build in the nuances of the minutia, and still fucking live your life. You gotta do it kinda recent to the event so things are fresh. You gotta try to not write the same fucking thing every day.

MV: So you’re pretty disciplined about it when you’re on tour?

MW: Yeah, try to do it every day on tour. It really helps me focus and play better. Diary worked out for me like that big time. Especially when I’m thinking, where did I blow clams? Can it go better? What stupid fucking things did I say? It’s kind of a self-critique thing too. You use your own self as a sounding board. I’ve heard of these kinds of techniques people do in therapy, they’re asked to do diaries.

MV: Right, I’ve heard of that too.

MW: So who knows … Even when Mr. Poe or Mr. Twain or Mr. Whitman, even when they were doing their trips, who knows. That’s what’s trippy – about the work, the person, the reason for the reason, the technique … That’s why human expression is interesting to me. Besides being fabric that kind of connects us, it’s also a way for us to express ourselves, like our fingerprints already do, but at the same time, kinda resonating on the common ground we all share. So what’s important at the end of the day with the diary shit is doing it. What is it D. Boon would say-- “The knowin’ is in the doin’.” That’s the diary idea.

Now the other way I write words is for tunes. And that’s a different trip, because you’re trying to serve the tune. I usually always start with the title. Just like with the diary you always start with the date. I need some kind of form.

MV: You start a song with the title?

MW: Always. Because it gives me some kind of focus. I’m not saying everybody’s gotta do it that way, I’m just telling you … Shit, I never thought I was ever going to be doing this. I got into music to be with D. Boon, I wasn’t really a musician. And uh, yeah … he got killed, and I kept going. I’m still a student.

MV: Had you written anything before the Minutemen?

MW: When I was a teenager I wrote one thing. It was called “Mr. Bass, King of Outer Space”. [Laughs] I can’t remember the music or even the words. But I do remember the plot, or whatever you want to call it, of the tune was I do a big bass solo and blow everybody off the stage. [I was] socially kind of insecure. I’d learned about bass hierarchy, that it’s where you put the retarded friend. It was like right field in little league.

Nobody D. Boon or I knew wrote songs. I’m 13 in 1970, so we’re ‘70s guys right? In the ’70’s culture there’s no clubs anymore, that ended with the ‘60s. Now it’s arena rock. So the performances are like Nuremberg rallies, there’s no empowerment. You’re sitting so far away, the band is tiny, all the lights … That’s not empowering. That’s like you’re at the fucking circus.

It was much different when punk, when the movement, came. It made everybody in the band way more equal. And especially with a guy like D. Boon. He wanted to put the politics … They weren’t just in the lyrics, they were in the way we made the music in the band. D. Boon was really heavy about that, which I’m glad for. Like he learned from R&B that the soul music guys would play really trebly guitar, really clipped, no power chords. So [by making his own guitar really trebly], he was making room for the bass, making room for the drums. He said it was like an economy, he wanted a more egalitarian economy.

MV: What did you think of that?

MW: It was trippy at first, we’re young men, you know. But punk was so fucking profound on us, it just made us rethink everything. Nothing from the arena rock experience. I think this is one of the things that made us embrace the movement even more. When the hardcore kids came out a few years later in the early ‘80s, they weren’t really rebelling against the old rock because they never knew it. In a way, we were much more reactionary than those guys.

MV: So when you started writing, you’d think of a title and go from there.

MW: If I got the title it would give me enough fucking focus that I could either bring the words in, or bring the music in, or bring them both in, so that—at least in my idiot mind—they would make some coherent sense. I say that because D. Boon would say that my lyrics were too spacey. [Laughs] You know that’s why on Double Nickels on the Dime I’m reading that landlady’s note (on “Take 5, D”). That was kind of—not a rebuttal, but me just having some fun with him. “OK I’ll try to be more clear here, more real, more real.”

At first we thought words were kind of like lead guitar or something in songs. It was mysterious what words were about. But when we saw the punk gigs … I remember D. Boon coining this phrase “Thinking out loud.” Ah – that’s what they’re for! You can actually use the music to express thoughts, feelings—that was totally new to us. Before that it was all about trying to copy some licks or something. The idea of using art—and I’m talking about poems, painting, all this stuff—to express stuff … It sounds naïve, but man that was a huge mind-blow for us in the ‘70s.

MV: You guys were also teenagers, that stuff blows a lot of teenaged minds.

MW: I also think that the stuff from the ‘60s had gotten forgotten already. Everything goes through these cycles it seems. I think we were in this time that was very much: “Well, we’ll take a couple people, they can be the elites and speak for us all.” And I think when the movement came, just like the Beat thing, and before that people like Woody Guthrie, before that people like the Dada people … It’s sort of like farmers and fertilizer—if you want a good crop, use a lot of shit. It seems like you need these things to inspire other kinds of reactions.

Even though it was a really fucking lame and stupid time, we were also very lucky. The Minutemen was in a very lucky place because no one knew exactly what to do with the movement, so you could help be part of that invention. Every time is a good time to be born, but for the Minutemen graduating high school in 1976 was just so lucky.

MV: Back then, how did you guys approach the musical side of things?

MW: Maybe us learning the Blue Oyster Cult and the Creedence helped us a little as far as getting licks together. But we thought that was really secondary. That’s what punk rockers taught us. Bands like the Urinals—the song’s all one chord! We thought that was so fucking econo … What’s the other word for it? Elegant, elegant. You just need enough. Like when you see a Vincent van Gogh painting there’s not too many strokes, there’s just enough.

Socially that opened us up to a whole bunch of wild people too. Those people in the early punk scene, they all were very deep. They were strange and weirdos, and that’s why they invented this parallel universe. But they were very interesting and inspiring. Now, down the road 35 years I’m talking to you. And it’s all because I was in a band with my buddy, and I was part of this movement. Actually, me and you probably have more common ground than a lot of my peers did in those days.

MV: Were you guys reading a lot back then? You mentioned poetry was inspiring.

MW: Yeah, yeah. As a teenager I was huge into the Divine Comedy.

MV: Already as a teenager?

MW: Yeah, I don’t know why. It was like some kind of puzzle to figure out. All the names, all the people, all the fucking weird-ass stuff, you know? Punishment, atonement, reward or whatever the fuck—trying to make sense of this shit. I don’t know how I stumbled onto it. It was in the 10th grade, so maybe 16, 17? So that was the first big poem I got into. Around the same time I got into Huck Finn. Before that I was reading a lot of science fiction. You know I’m born in ’57, so when I’m a boy it’s all about the space race, the Soviets and US. So I was reading a lot of this stuff, Ray Bradbury, Mr. Dick, even some [Robert] Heinlein, Frederik Pohl, and Roger Zelazny … these science fiction things.

The other thing was dinosaurs, I was into dinosaurs. So I think this was one reason … Well, what happened was my mom got me this World Book encyclopedia, the door-to-door guy sold us these encyclopedias. They start from A and go to Z. So when I got to the Bs I found this guy Hieronymus Bosch, I think that might have steered me toward Dante too. It was so bizarre, all these little creatures – which kinda reminded me of the dinosaur stuff.

And D. Boon got me into history, that’s what he read. I wasn’t that much into non-fiction, I liked fiction.

MV: He read more non-fiction?

MW: D. Boon read almost totally non-fiction. I can’t remember any fiction he read. So that influenced me. I got into that stuff because I wanted to talk about what he was talking about. He liked history a lot. As far as fiction, well because of the punk rockers teaching me, like Raymond Pettibon, I found out about Jim Joyce. So I got really big into Ulysses. In fact, almost all of my songs on Double Nickels on the Dime are inspired by Ulysses. Writers started to become a big source of inspiration for me. And the poet I was into at the beginning of punk was Rimbaud. “The Drunken Boat”, A Season in Hell, “Democracy”. I even put music to some of these things, even though he’s writing in fucking French and I’m reading translations. But this idea where he had colours for the vowels … I was just at a very impressionable time, that thing where anything goes. As I was saying the movement was profound. So I got into all this kind of literature, wild-ass stuff. A Bohemian kind of thing. The Beat people – Mr. Burroughs, Mr. Kerouac, Mr. Ginsberg’s Howl, Mr. Pynchon. I guess he’s more psychedelic, with Crying of Lot 49, and then Gravity’s Rainbow. The 60s thing …

See I’m a boy in the ‘60s. ‘69 I’m 12 years old. It was a strange place. I saw a lot of things. I saw Mr. Oswald shot to death on TV. I saw people on the streets for civil rights, taking things into their hands about wanting change with the war in Vietnam. I’m in Pedro because of Vietnam, ‘cause my pop’s a sailor. So I am kind of a product of those times. I’m not really a ’60’s person, but it did have a huge influence on me I think. Just as, in a weird way, I’m not a ’70’s person either, but the ‘60s and ‘70s really grounded me. Made all my sensibility. Made me really encouraged to go for something and refuse another thing. And wanting to get in on this, I don’t know … further, beyonder, you know, the Last Poets. [Laughs] I was really into Last Poets. It’s trippy how rap came out of that. It made total sense to me when that happened. Kinda like black punk.

One thing about being a ’70’s teenager, [it was a] pretty narcissistic generation. You didn’t want to know about stuff that was 5 years older. It was really weird. We were all about ourselves. When I look back on that now, it was ridiculous. Very self-satisfied. I think it was because some of the counter-culture of the ‘60s got co-opted by commercial things in the ‘70s. And I think some people thought this was some kind of victory. That all the work was done. So thank god there was this tiny little movement that me and D. Boon fell in with, and music was one of its components. A lot of the dudes you could tell were not musicians. A lot of them were artist people. They were provocateurs. They wanted to make points. They wanted to be a little adversarial, a little confrontational. And then you know, this was kind of pushing buttons from our earlier programming seeing this [civil rights] stuff in the streets on the TV. It’s very interesting. We couldn’t really articulate it, but I think it does come out in our work.

MV: Yeah, I can see that.

MW: You know, McCarthy--a band on a record in 1980 talking about McCarthyism … I mean, this is just bizarre. But that’s what we were feeling. The new boss was Mr. Reagan. I think you guys had Mr. Mulroney, and over there in England was Ms. Thatcher.

MV: That’s surprising to hear that your interest in both Bosch, who you used for your Hyphenated-Man album, and Dante, who you used for Secondman’s Middle Stand, stretches all the way back to when you were a kid.

MW: Yeah. Richard Meltzer says that I’m his favourite sentimentalist! [Laughs] Maybe it’s weird going back to little boy shit.

MV: Dante and Bosch isn’t really little boy shit.

MW: [Laughs] Well, I mean my boy experiences. I’m not saying the subject matter. In fact, I was told by a high school teacher that I shouldn’t be reading that shit. Some lady at San Pedro High. She wasn’t an old lady either. “This ain’t a story for a young man”. I said, I’m sorry, but I kept reading it, I wasn’t gonna stop. In fact, I read different people’s translations. The Ciardi was the first one, but then I found the Longfellow one. There’s different ways to try to do it – with blank verse, or to try to keep the little three-rhyme thing going. In a way, it was like playing with a fucking Rubik’s cube, you know? It’s very fascinating to me. I don’t know about the subject matter so much. But the work itself is really fascinating. Just looking at anything and taking it apart.

MV: With Hyphenated-Man, for example--I know that was also partly inspired by when you participated in We Jam Econo [a 2005 documentary about the Minutemen] and started listening to Minutemen songs again for the first time in many years.

MW: You’re right.

MV: Did the Bosch connection just kind of pop up again then?

MW: No … I was on tour with the Stooges in Madrid at the same time that I’m listening to the Minutemen, in 2004—actually it was the 400th Anniversary of Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote, another great book, they had a big festival. Anyway, the hotel we’re at is right next to the fucking Prado. Prado’s got 8 Bosches. I couldn’t find them at first because they call him El Bosco. But I found El Bosco and saw them in real life for the first time. And it’s not like a picture in an encyclopedia, man. In fact, he painted on wood, they’ve got no glass so you can put your face right up there and see. And it blew me away. For some reason having this experience of re-listening to the Minutemen, I thought man this [Bosch’s work] is like a Minutemen album, or Minutemen gig, a bunch of little things to make one big thing.

MV: That makes sense.

MW: You know what happened? When I started hearing the Minutemen, I wanted to play music like that again. But then I owed it to D. Boon and Georgie not to rip them off. So I thought to myself, what if I made another opera, and I’ll write about something the Minutemen would’ve never wrote about—being a middle-aged punk rocker! [Laughs] So that became the libretto. I felt OK about that.

I wrote the whole thing on D. Boon’s Telecaster. I’m not that much of a guitar player, but I did it on purpose so the bass would come second. I was doing all these things so it wouldn’t be too much Minutemen, because I was feeling guilty about ripping my old band off, you know? There’s too much of that shit going on already. I don’t have to be another one doing that. So what I did is I tried to use that as like an appropriated thing, to make a new thing.

MV: You wrote all the guitar parts first?

MW: I wrote the whole thing, all 30 parts on D. Boon’s guitar, his Telecaster. You know, symbolically, it was very emotional. Talking about yourself is a fucking scary thing. You gotta lay it out there, but it’s still gotta be a fucking song. So I wanted to bring things out, be brave enough to say ‘em, but still be artistic with it. And D. Boon was a painter, you know, besides a guitarist and a singer and a songwriter. So I thought that he would just somehow help me, by using his machine. I even have the demos, all 30 of them. I recorded them all.

I’m glad you brought that record up, because that’s a real important one in my mid-life. It’s one I never would have thought of as a younger man. I thought it was all downhill after Double Nickels on the Dime. [Laughs] I wasn’t trying to do another Double Nickels on the Dime. I was visiting some earlier place in my earlier music, but I was trying to talk about something very contemporary, my life right at the moment. I even wrote it in order. Though at the end of the day I took the middle song and put it at the end, because the last song [“Man-Shitting-Man”] turned out to be a real downer. The way the mind works – just like looking at those Bosch paintings, they read from left to right – people might think that “Man-Shitting-Man” is my kind of, I don’t know, conclusion or summation of the whole trip. It’s not. Middle age is about reconciling a lot of things, but there are some things you can’t reconcile, and a lot of that is man’s inhumanity to each other, the way we treat each other. There’s no good reason for it, ever. And I had acknowledge that or else I wasn’t telling all the truth. That’s why I had to have “Man-Shitting-Man”. But I didn’t have to have it last.

MV: Have you ever had writer’s block?

MW: Oh yeah, it can come. It’s one reason why I used other people’s words. If you look on Double Nickels, they’re not all Boon/Watt/Hurley. If I used other people’s words, all of a sudden I’d get different licks coming out of my bass. Writers’ blocks, they come. There was a period in the early 2000s after that sickness. I had to tour a lot to pay off … You know about our incredible, wonderful medical system? $36,000. So I had to do a lot of tours. And I was happy to pay it off, because I was alive. [Laughs] But I had to play gigs where I was doing lots of cover songs … I was going through a little blockage period. Between the first and second opera.

MV: So the Secondman’s Middle Stand was hard to write?

MW: Well, it was easy to write because it was about that fucking sickness that almost killed me. I used the Divine Comedy as a parallel. The sickness was the Inferno, the healing was the Purgatory, and getting to ride my bike and kayak and play bass, that was Paradise. I wrote it pretty quick, but in the meantime I had to pay off these debts and do a lot of touring. Two tours a year. Bands like the Jom and Terry Show, The Pair of Pliers … I mean these bands didn’t even make albums. I put them together just to tour, just to get the money. So the one good thing was, even though I had some writer’s block, I was still performing. That’s kind of treading water a little bit, but it’s better than doing nothing, like putting the bass down.

MV: Finally, if there’s one word you’re associated with, it’s "spiel". Where did that come from for you?

MW: It’s Yiddish. A lot of show business talk is Yiddish because a lot of these cats—well fuck, they created the culture! There was a time with no TVs and theatres right, and so cats had to travel town to town ... Vaudeville. And in a lot of ways I feel very connected to this culture. The touring life, you know? I play rock and roll music, but the touring and that part, that’s way more into vaudeville culture. So I use a lot of these Yiddish words—I think it was a mix of Hebrew and German, with Polish and Russian. It comes from Jewish Europeans who immigrated over here and worked in theatre and then movies and in music too. Entertainment culture.

I got to play with the Stooges in Tel-Aviv and it was trippy, the young people there didn’t even know what Yiddish was. They speak Hebrew. So it was specific of a certain kind of people at a certain time. But this idea of workin’ the towns—you could say Shakespeare was [doing that], I mean all kinds of people were in this tradition. So spiel comes from this. And shtick, and kvetch and kevel and schlep. All these words come from this tradition I see myself as part of.

MV: But “spiel” was a Minutemen word too. You guys were using it already back then.

MW: Spiel was like your pitch, trying to sell somebody something, not an item so much but a point of view. And it doesn’t have to be jive. Of course some spiels are jive, but some spiels have a lot of integrity. I think the Minutemen used it for a self-humiliation thing. I told you, we were pretty insecure about lyrics—we didn’t even know what they were for. So if you were already making fun of them, maybe you’d be a little more brave to do it. So that’s why we called our lyrics spiels. Also, interviews we called spiels. Every time you opened your fucking mouth that was a spiel.

MV: Well, it kind of goes with D. Boon’s “thinking out loud” idea.

MW: Absolutely, absolutely. These things were empowering to us. It was a form of expression, a kind of power for little guys like us. Not power over people, but power to be creative.

| On and Off Bass by Mike Watt Three Rooms Press, 2015 Description from the publisher Three Rooms Press is thrilled to announce long-awaited European distribution for MIKE WATT: ON AND OFF BASS, a book of photos, poems and tour diary snippets from Mike Watt, the world’s foremost punk rock bass player (Iggy & The Stooges, Dos, Il Sogno del Marinaio, missingmen, secondmen, minutemen, fIREHOSE and more). The New Yorker calls MIKE WATT: ON AND OFF BASS “unusual and beautiful.” The LA Weekly raves, “the photos are strikingly inventive, revealing yet another side of this modern-day Renaissance man.” MTV calls it “a charming, well-shot document of a the legendary punk rocker’s photographic dabbling.” |

RUSTY TALK WITH GREGORY BETTS

Gregory Betts

Gregory Betts Tom Cull: You are described as both an “experimental” and an “avant-garde” poet. Are these two terms interchangeable?

Gregory Betts: No, well at least not for me—and, furthermore, in some respects they are oppositional. For me, experimental means willing to try something totally new and risk failure. Avant-garde, on the other hand, refers specifically to writers who try to change the world outside their writing through their writing, who care enough about their society/community to want to lead it somewhere. “Come the revolution,” as Stephen Collis implores. The former looks inwards towards the form in relation to other kinds of writing and modes of expression and risks saying something that might well be incomprehensible. The latter looks outward towards the world beyond the page and takes a stand. To be clear, in most cases and for most people these terms are interchangeable and they get bandied about freely without much investment. They are used to refer to just about everything. So what I’m highlighting here is the thing that makes them both appealing to me especially in their difference.

Conversely, when “avant-garde” means something akin to “innovative” it’s just another boring substitute for capitalism. “Experimental” is too often synonymous with self-indulgence and poor editing. I’m not sure either term really applies to my writing: I don’t think I’ve been socially ambitious enough, as yet, to be called avant-garde, and though I fail and fail often I don’t think any of my failures amount to anything spectacular enough yet to really register on that other front. Kenneth Goldsmith recently failed in trying to make poetry out of police shooting victim Michael Brown’s autopsy report, and failed spectacularly. I’m not sure what he was going for exactly, but I condemn the casual cruelty of his appropriation of race. Like Frankenstein, it’s like he lost the human perspective in his pursuit of the experiment. The avant-garde and experimentation are interchangeable inasmuch as they are both well-littered graveyards of catastrophe and disappointment.

TC: Have you always written experimental poetry? What draws you to experimental poetry over more traditional forms of poetic expression?

GB: Hmmm… I suppose I see experimentation as part of the poetic tradition, indeed intrinsic to the kind of writing I care most about—and I don’t think “traditional” writers like Coleridge, Blake, or Byron or Atwood would disagree (though Tennyson would). When I work with permutations, for instance, I feel a connection to bpNichol and Brion Gysin and Robert Filiou and, more recently, to Angela Rawlings and Margaret Christakos. Is this so different from the ancient Sanskrit epic poem “Kiratarjuniya”, that contains loops, anagrams, repetitions and other language games? Perhaps the bigger split is between expressive and disjunctive writers. In Canada, ever since Phyllis Webb let air and space invade her page, silence has been thematized as an appropriate response to what the Situationists called “the present multiform crisis” of Western colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. M. NourbeSe Philip more recently highlights the necessary task of letting language collapse for different but related reasons.

I am interested in writers that explore language as a problem as a metonymy of the boundaries of human experience, and especially those who then experiment in search of new portals to find a way out or at least to find a new elsewhere. If we want to expand the possibilities of the human, we need first to confront the limitations of our primary technology. Language is not just our point of access to the world, and to other people (or creatures or machines), but it is our principal point of contact with ourselves. Poetic expression that does not register the limitations of the tool it is using to reflect or pontificate on the world always seems too comfortable within the present world.

TC: You wrote The Obvious Flap (Bookthug, 2011) in collaboration with the poet Gary Barwin. Your internet poetry is also highly collaborative. What appeals to you about collaboration?

GB: Collaboration is exciting—you give up the very thing that most limits poems, the I-self, and yet somehow still learn from within the fold of your own production. It’s the schism of voices that creates a fracture, an opening to something disturbingly new. And you have to take responsibility for saying something that you would never say on your own. How delightfully disturbing! This is especially true when you work closely with a writer as inventive and open as Gary Barwin. My other collaborator was Facebook. All of Facebook is more conservative an imaginative space than Gary Barwin.

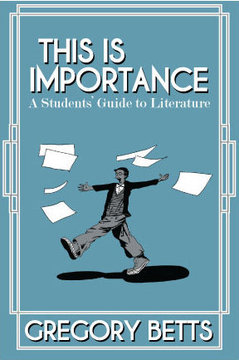

TC: I want to ask you about your two most recent books. First, This Is Importance (Poplar Press, 2013) is a collection of mistakes comprised from years of marking student papers. You preface the collection with an essay in which you celebrate mistakes as a necessary part of the learning process. Do you distinguish between mistakes that are born of trying and mistakes that are born of a lack of trying?

GB: In the context of an essay, while grading, that’s a rather subtle difference! In that project, especially, I was interested in inadvertent insights—errors that are so far off the mark that they reveal something completely otherwise (other-wise) by mistake. It’s the surprise and the misdirection that make them so appealing. What I realized, as I was grading papers filled with errors such as you’ll find in the book, was that I was not reading those papers with my poetry brain but with a rote, evaluative brain. How dull and limiting! And what a mistake! Keeping myself attuned to the poetry of the error is a way of making the grading process weird and wonderful. Also, I bring them into the classroom when I find them to talk about (after we have a laugh) what went wrong and how to learn from it. Humour and error are definitely a large part of my pedagogy, and how I learn things for myself too.

TC: Part of this process has to do with learning to laugh at our mistakes—to enjoy the humour of transgression. As an artistic form that champions transgression, why does poetry seem take itself so seriously?

GB: That’s a critique that Ryan Fitzpatrick and Jonathan Ball sought to address (and contest) with their recent anthology Why Poetry Sucks, a collection of very funny experimental poems. They make the subtle but important point that weird things have a pleasure in themselves, even before you get into all the serious stuff going on. Thinking about a fishchair or a carsoon or even completely made-up words (free words, my son calls them) is an invitation to imaginative play. The avant-garde is built on this kind of play. It becomes so so serious when that upriotous fun is aimed specifically against dominant values, but to me that just adds to the pleasure even as it grimly acknowledges the mess of the world.

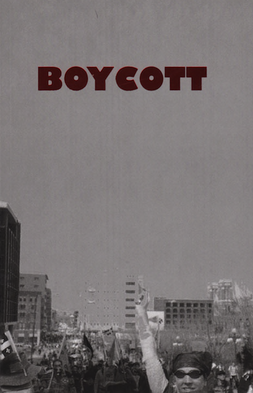

TC: Your most recent book Boycott (Make Now Press, 2014) samples and assembles statements taken from boycott movements from around the world. What interests you about the concept and practice of boycotting?

GB: Well, ever since I was a kid, I’ve been involved in boycotting. I learned, over a cigarette behind my high school, that McDonald’s sold “100% Canadian beef” but that “100% Canadian beef” was actually the name of a company that raised cattle in the Amazonian rainforests. Nauseated, I have never stepped foot in one since, even though they have reversed that particularly egregious abomination. I’ve picked up a few more boycotts over the years, and, twenty years later, finally decided to spend some time investigating the tool and what I was actually participating in by boycotting. What I discovered was disconcerting: boycotts are one of the most powerful tools of progressive social movements (which is how I learned of them), but they are also the expression of enormous power differentials that reinscribe things I’m much less comfortable with. The book, thus, starts with boycott movements against the big powers and the leading economies, things most people are comfortable with, but gradually addresses boycotts against increasingly marginalized groups. There is an American-led boycott movement against Haiti for fuck’s sake! Boycotting, I have come to realize, is an ambivalent tool that can be used for good and evil. Ultimately, the ability to boycott only reflects one’s ability to withhold capital, which of course privileges those with the most capital. I’m implicated in those realizations.

TC: This Is Importance employs a more standard typographical format—the lines have regular margins, spacing, and categorization. Boycott, however, employs a wide spectrum of typographical variations. Both books are comprised of found poems; how, in each book, did you decide upon the arrangement of the lines on the page?

GB: In This is Importance, the semantic unit was the sentence. These were logical chunks that were kept in the simplest form possible in the book. In Boycott, though, a much more challenging work because of its varied ideological content, the form attempts to respond to and bring out key dimensions of each statement. The twists and turns of the line breaks highlight different stress points in the statements, forcing pauses onto revealing ideas in the language of global boycott movements. It also, I suppose, registers my basic discomfiture with the language I was tracking and including in my own book. Some of the lines are very, very funny, but there is a basic advantage they are all based upon that I am happy to see broken up and disrupted.

TC: Is it true that actor Shia Labeouf plagiarized you in his defense of earlier charges of plagiarism? Have you ever plagiarized Shia Labeouf?

GB: Yes, rather brilliantly in fact, in the context of an interview in which he was expressing himself only through quotes. It was quite a performance, reminiscent of Echo struggling to speak in the words of Narcissus. Only, in this case, the part of narcissism was played by all of Hollywood itself. I have to admit that it was only after some editors on Reddit discovered the plagiarism that I learned who Labeouf was. The whole ordeal was strange and weird in the way that only LA/Hollywood can get. He flamed out, backtracked, and became an eccentricity in a lulled American moment.

Speed round!

Tom Cull: What is your earliest memory of writing creatively?

Gregory Betts: I mowed the lawn, but one day mowed around an especially tall dandelion. My parents made me go back and mow it too. I wrote a dirge elegizing the flower. Earnest, rhyming, and pitifully lost in expressing over-wrought emotion.

TC: As a child, did you read poetry? Was poetry a part of your childhood?

GB: Just the usual things—Dennis Lee, Shel Silverstein, Dr. Seuss. In grade 1, I discovered the Greek myths and consumed them voraciously. I preferred novels and devoured the works of Marshall Saunders, James Herriott, and especially Richard Adams. When I was about 8 I switched over to more adult fare and ripped through Ken Follett, Dick Francis, Stephen King, Peter Straub, and the like. It was Robert Hunter, when I was 14, who turned me on to poetry. Ginsberg and Shelley became big influences at the outset.

TC: How did you become a writer?

GB: By publishing a book.

TC: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process?

GB: I suspect I would do much better at this whole thing if I had a process. The only thing I focus on is the individual project and I try to do everything I can to fulfill its unique potential. I also make an effort to never write the same kind of book twice.

TC: What are you currently working on?

GB: Right now, I am just finishing up another collaboration with Gary Barwin, writing a book on the Vancouver avant-garde, editing a book of essays on Marshall McLuhan and Sheila Watson, finalizing a new scholarly edition of the first avant-garde novel in Canada, and digitizing the complete works of bpNichol.

RUSTY TALK WITH GREGORY BETTS

GREGORY BETTS'S MOST RECENT BOOKS

Gregory Betts

Wolsak and Wynn, 2013

Description from the publisher

Poet, novelist and teacher Gregory Betts has an ear for a well-turned phrase and an eye for captivating errors. In this highly amusing collection, Betts has pulled together some of the best misinterpretations of literature that he has come across in his years of grading papers. With an introduction on the importance of learning through error in education and a full complement of confusions on authors, styles and the point of reading literature, this book will delight English teachers everywhere.

Characters are all born in literary Canada.

Rising Action is the period before the climax where there is a build-up to prepare the reader

for the ultimate high.

The narrator is bias.

All literary devices die.

The average reader expects grammar and punctuality in every sentence.

Female protagonists take no heed to spiritual warnings.

The story is so complicated, so devious, that nobody could possibly understand it, let alone

me.

It is certain that there is no conclusion.

Writing is one way to control the truth.

An unreliable narrator is one whose recitation of the plot is strongly compromised because

of madness, blindness, or biasness.

The past tense represents an attempt to reflect on what has already happened to the narrator, such as future failure.

Realist writers have both feet grinding in the world.

Form causes everything.

The author speaks volumes in his novel.

The narrative is the experience of everything: everything that can happen.

A period in a sentence suggests death.

On Poetry

The poem begins with the poet’s language.

The poet attempts to salvage that which is beyond recovery.

Poetry has many complex dimensions: it can be revolting or disgusting.

Language makes the poem seem a certain way.

Seeing 4 lines per stanza makes you believe that it is a Quartrain.

Language is extremely useful to a writer.

A narrator is the unreliable voice inside a poem. We find this out at the very end.

On Reading

Reading is a painful experience, although pleasurable.

Reading creates a sinister impression of the imagination.

Readers tend to miss the deeper meaning of a text because they tend to focus on me.

Profound Forisms I

The author uses a forism to express a commonly held belief.

Beauty is temporary therefore one should procreate.

Mortality is the result of time.

The alphabet has been a major influence on many poets.

In general, poets are striving to generate taboos.

When lust presents itself as attainable, desperate bachelors act on the opportunity.

Reality is hard to live in.

School makes men dream of war.

Homeless people are undeniably alive.

Most people do not know that they fear what they do not know.

We know nothing of reality.

In conclusion, it is always important to know which work is being read.

Children are a stigma of innocence.

There is never a situation where coherency can exist.

Death can be viewed as a bad position. Perhaps the worst.

Exposition is the future before the flashback.

Literature is a very important mode of transportation.

Marxism theories the text.

I get a shady feeling from story telling.

Most people worry about customized babies.

It is difficult to bomb someone softly.

Gregory Betts

Make Now Books, 2014

The

word boycott originated in Ireland during the “Land War” from

the name of Charles Boycott, the agent of British absentee

landlord, Earl Erne, who was subject to social ostracism

organized by Michael Davitt’s Irish Land League in 1880.

We must send a clear message that human death, ecosystem

destruction, and collateral damage are unacceptable in the pursuit

of oil. We must use our dollars to vote against this type of

corporate behavior!

Gosh forbid they should provide full-time employment with benefits or a decent

wage.

I hate Ohio so much I made a website.

I'm not the

kind of gal

who cries

"boycott"

easily,

but staying in Thailand makes no sense for anybody.

I’ll take a great beer over cannabis any day, but I will boycott

Belgium-owned Anheuser-Busch. I’m not going to Belgium any

time soon.

I’m not going,

and I’m looking forward

to not going.

If you're from out of state, beware! Don't drive through Illinois.

It's a trap.

You Boycott Me

Will you boycott me upon reading this? will you boycott the response after reading

this?

I don’t care if you boycott me, or curse me and cause me supreme amounts of pain. If

you boycott me, you are only hurting me. I will be forced to suffer the consequences.

You throw me in the middle of the ocean, force me to live with tigers.

Where is my rights to express my freedomness when you boycott me? An average guy

on an average wage? How cartel of you.

Actually, I prefer it. But tell the truth: You hate Americans, period. Just be honest

about it.

If you boycott me, I will boycott isreal, and I am serious about this. think about that

before you boycott me. Tit for tit. This is collectivism. I will not send you any

electricity.

You boycott me. So at the end of it all. What really happens? Nothing.

Boycott Argentina for their sinful ways

Boycott Australia in retaliation for the country playing host

Boycott Austria and their tourist industry and buy your guns somewhere else

Boycott Bahrain? Boycott Oman? Boycott Iraq? Boycott Indonesia? Dream on... these

are American Client states. These are vital Customers

I say let's boycott Barbados altogether and all things Barbadian. And further

more, in protest, I refuse to even mention this nation by name

You say boycott Bolivia? How about the rest of the world boycott you?

I boycott you who boycott girls, without girls, you cannot exist

and I boycott you Canada!!!

Really, Pampers? Must I boycott you too?

I boycott you blog that is full of shit.

I boycott you because I hate ads that much.

I boycott you illiterate Facebook applications.

The reasons I boycott you? At first, it was simply because it was so hard.

Here’s my question: should I admire you for sticking to your unnecessary, overtly

sexual guns or should I boycott you because of, um, the same reasons?

How can I boycott you when I never darken your doors to begin with?

I boycott you Naomi Klein. This comment has received too many negative votes to

show. Click hide.

I boycott you because you are so ignorant that you are mixing art and politics

together. Get a crash course on Art 101!!

When Chavez is removed, then the boycott can end, but not

before. T-shirts till the end.

If heaven is a place on earth, hell is in Norway.

If it’s so great there, why do they speak Norwegian?

As Americans if we allow ourselves to be treated like offal by

these corporate tyranists then are we not also ready to accept

tyranny as our form of government?

RUSTY TALK WITH GARY BARWIN

Other recent books include Franzlations (with Hugh Thomas; New Star), The Obvious Flap (with Gregory Betts; BookThug) and The Porcupinity of the Stars (Coach House.) He was Young Voices eWriter-in-Residence at the Toronto Public Library in Fall of 2013 and he is Writer-in-Residence at Western University in 2014-2015. Barwin received a PhD (music composition) from SUNY at Buffalo.

Barwin is winner of the 2013 City of Hamilton Arts Award (Writing), the Hamilton Poetry Book of the Year 2011, and co-winner of 2011 Harbourfront Poetry NOW competition, the 2010 bpNichol chapbook award, the KM Hunter Artist Award, and the President’s Prize for Poetry (York University). His young adult fiction has been shortlisted for both the Canadian Library Association YA Book of the Year and the Arthur Ellis Award. He has received major grants from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council for his work. Recordings of his work can be found at PennSound.org and on his YouTube channel. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario and at garybarwin.com.

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Gary Barwin: I was a single cell. There was a flurry of macromolecules—DNA, RNA, a wad of proteins—and then I wrote another cell into being and I became two cells. I kept writing until I was millions. This was my mother tongue before I had a tongue. There was no editing, until my father cut my nails.

Unless, my first creative writing memory was when I was 6 and writing on little cue cards, making up a writing system that seemed to hold the largeness, the numinosity of what could be said. I wrote a bunch of strange little sentences that were spells or poems in this made-up script that didn’t “mean” anything. And I do remember writing “Cosmic Herbert and the Pencil Forest” a short story in Grade 5 and publishing it to sell at the school “White Elephant” sale. My first publication.

KM: You are probably one of the most diverse writers in this country. You are a poet, a fiction writer, a children’s author, a performer, an artist, and a musician—is there an art form that you have not tried but want or plan to? And how do you decide what genre or form a project will take?

GB: There are so many things I’d like to try. I can’t help wanting to try my hand at a variety of things. I feel that there are so many exciting and inspiring ways to imagine writing, how could I just settle on one?

I see a continuum of approaches to creative work. On one extreme, there are writers like Samuel Beckett who worked his entire long career on narrowing the focus of his writing until he arrived at the laser-like minimalism of his later work. And then there are the writers who explore many different modes of creation, all part of one big messy creative ecosystem. bpNichol was one of these. The composer/writer/visual artist/performer John Cage was another.