A REVIEW OF JILLIAN TAMAKI'S

SUPERMUTANT MAGIC ACADEMY

BY ADÈLE BARCLAY

The Rusty Toque | Issue 8 | Reviews | Graphic Novel | June 30, 2015

|

In graduate school I took a course on comics and graphic novels. The professor—recently tenured and thus newly empowered to stray outside the bounds of the English canon—assured us the course title would appear on our transcripts under the neutral designation “Literary Forms and Genres.” Apparently, we needed to be covert about our clandestine scholarly forays in the academy. Even so, comics are slowly becoming part of the literary establishment, garnering prestigious awards and receiving mainstream and scholarly attention. The pressing question isn’t whether comics are worthy of study, but, rather, what happens to the mutants and misfits when the Ivory Tower takes an interest in comics?

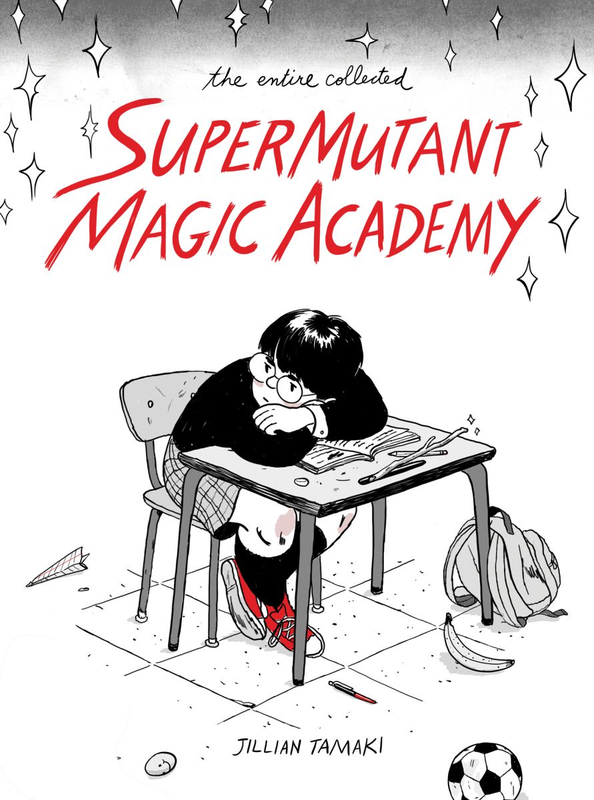

In the case of Jillian Tamaki’s SuperMutant Magic Academy, they get weirder. Originally a serialized webcomic, SuperMutant Magic Academy documents the micro-dramas of teenagers attending a prep-school for mutants and witches. A mix of familiar high school, magic, and superhero archetypes poured into six-panel strips, the collection brings together the online series in print. Reading the entire series in the new paperback edition confirms Tamaki’s skill for taking a recognizable world and imbuing it with its own defiantly irreverent wit. The bizarre realm of SuperMutant Magic Academy is tinged with the eeriness and pleasure of a lucid dream. Tamaki is the co-creator (with cousin Mariko Tamaki) of the bestselling, critically lauded graphic novels Skim and This One Summer, both stunning coming-of-age long-form narratives. While SuperMutant Magic Academy also focuses on adolescence, the comic bolts in the other direction, opting for episodic bursts of offbeat humour. Smart and bratty, SuperMutant Magic Academy tackles coming of age by cutting class and chewing up popular tropes. The cast is like the members of The Breakfast Club attending Hogwarts, trying to make it through the day instead of saving the world. Channeling Harry Potter realness, Marsha pines for her best pal, the popular and pretty Wendy, who is a fox (she literally has fox ears and routinely transforms into a fox to hunt small animals for lunch). The radical feminist Francine stages art happenings that shock and move her classmates, but fail to impress the teachers (“Guerilla performance art? A little… seventies, no?”). And the football jocks contemplate homosociality while Everlasting Boy endures the passage of time, repeatedly disintegrating and trudging back to life. These juxtapositions of barbed jokes and fantastical oddity permeate the collection. And through them the book takes jabs at sexism, racism and homophobia in unexpected and outrageously funny ways. In one example, a strip begins with a throwaway gay joke about an assigned reading of Oscar Wilde and unfolds into a life journey of domestic queer bliss. The kids’ superpowers are used to enact and take the piss out of stereotypes. Behind the cheeky stance, SuperMutant Magic Academy is empathetic in its depiction of ordinary ennui and anxieties, reaching out to the non-magical adult audience and fulfilling the back cover’s invitation—“The kids of the SuperMutant Magic Academy want to be your friend.” The kids are petty and marvelous as they navigate daily minutia. Tamaki’s treatment of their plight is caustic and, despite the supernatural backdrop, relatable: she uses magic to exasperate the mundane rather than escape it. While flying on broomsticks, Marsha tries not to perve on her best friend. In this fantastical world, superpowers still aren’t enough to summon the energy to make nachos nor can they supersede the influence of social media in making and breaking friendships. The comic-book teens fight and flirt, carrying out typical shenanigans. And, of course, prom coincides with a prophesied quest. But the real twist in this universe isn’t the magic: it’s the off-the-wall sardonicism. Tamaki wraps her characters in layers of satire, but the comic doesn’t smugly wear irony like a badge. Tamaki’s humour, like her line, is swift. The strips playfully bounce from sharp to wistful in tone and along a vast scale—from the cellular level to the cosmos. The drawing is dexterous too. Each character is simple yet distinct in appearance, rendered to effortlessly carry the weight of high school attitude and magical/mutant identity. The illustrations are black and white with the occasional splash of red for blood or lava, but Tamaki punctures the black-and-white routine with one particular strip that she casts in teal and mauve, using the change in colour to conjure Alice in Wonderland awe. While the strips vary in polish and a few are sketch-like, this inclusion of perfectly etched illustrations with fuzzier intervals conveys urgency and confidence. The warped wit emerges from precise and quick strokes alike. Tamaki is in possession of a fine talent for illustration and storytelling, which is obvious no matter if her work is categorized as graphic novel or comic. One strip in SuperMutant Magic Academy skewers the distinction between the two: a boy chides his date for reading superhero comics because of their blatant sexism, extolling the virtues of graphic novels that exude the candied-over misogyny of high art. With SuperMutant Magic Academy Tamaki proves her mastery of the comic, its highs and/or lows. |

ADÈLE BARCLAY’S writing has appeared in The Literary Review of Canada, The Pinch, Poetry Is Dead, Cosmonauts Avenue and elsewhere. Her debut collection of poetry was shortlisted for the 2015 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in 2016.