A REVIEW OF ALEX LESLIE'S

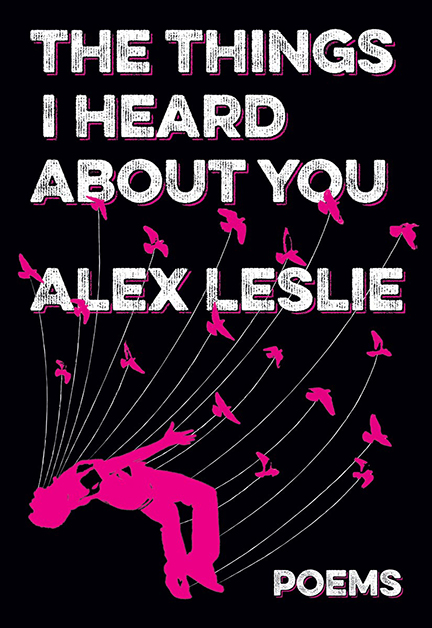

THE THINGS I HEARD ABOUT YOU

BY JUSTIN LAUZON

The Rusty Toque | Issue 8 | Reviews | Poetry | June 30, 2015

|

When it comes to good writing, many have emphasized the need for rigorous editing, but my favourite quote comes from Nick Hornby: “Anyone and everyone taking a writing class knows that the secret of good writing is to cut it back, pare it down, winnow, chop, hack, prune, and trim, remove every superfluous word, compress, compress, compress ...” Why he chose to use so many words to explain this concept is an irony I can’t explore here, but this clash between paring down and expressing meaning dominates any great piece of writing, just as it does Alex Leslie’s first collection of poetry, The Things I Heard About You.

In the pages of The Things I Heard, Leslie accomplishes the task of making art out of that painful editorial process. Each section of the collection is composed of four prose poems. The first of every section is a weighty prose block running from a half to a full page, sounding like an exquisite journal entry. Leslie attacks the heart of the sublime with pinpoint accuracy, and decides to present language in its rawest form. I don’t mean to say raw as in vulgar, or uncensored, but rather, her language assumes the quality of being unedited--erratic, stunted, and with little navigation. It is a welcome change. As each section progresses, the poems gradually diminish in size, using fewer and fewer words, extracting deeper and varying meanings. Each poem slips into a new form, transforming into a shorter expression of sublimity. As each four poem section is gradually edited--or as Nick Hornby would say, sharpened, mauled, compressed, pruned, reduced--it is also reorganized, ending with a piece sometimes no more than five words: “Bird in your chest, riptide.” But the magic of every poetic-quartet is highlighted in that liminal space between once section and the next. Once a poem ends, the word “smaller” is written below it, almost as an afterthought, and carries us on to the next poem. The word is ominous and alone, saying more by itself than any of the other words written by Leslie. It is that dreadful editor’s chant that makes every writer heave glassy-eyed frustration onto the keyboard--smaller. It is relentless and all powerful--smaller. It is writing. Even more impressive is how Leslie takes on this highly restrictive self-imposed editorial process. Leslie opts to forgo using any new words outside of those in the first piece of the quartet. It is as if Leslie, the master composer, has created a long playlist to tell us a story, and through the use of a broken shuffle button, shortens the list to a single song. More often than not, Leslie gets it right, and shows us that the same thing, if not more, can be felt without wasting our time. Take the second and final poems in “Archery for Beginners”: The sky opens and you sail through, speared. Arms binding your body--deux ex machina! Purpose like an object. Every object, the kite screamed, black. Escaping, I walked to you. Tipped into skipping breaths, climbing rippling ladders of thin eyes. Whistles in bones. I should have known you couldn’t be taken. I keep a silk kite, attack, your terror, my chest. Followed by this, two poems later:

I open you like a history of spears. Sublime and enchanting, The Things I Heard About You is perhaps the best writing lesson a young poet can get. Not only because of its insistence on the briefest of sentiments, but also because of its control over the long winded. I feel the entire collection screams that words can be reduced to a finer and stronger potency. “Smaller” the unnamed voice repeats--or demands--and, as the writer concedes and the poems diminish in size, resonance blooms in the silence that is left over.

But while every piece is broken down, reshuffled, and sharpened, don’t be too hasty to skip to the final poem of every section. In fact, while some of the one line vignettes may be breathtaking, they can and do, at times, fall short of meaning, elegant construction, and even beauty. The final poem in “Albert Bay to Port McNeill” conjures little of the awe found elsewhere in the collection: We the only. Flute, you, arms out, white loops for our ocean. It feels messy, like an uneasy bricolage of words left over, instead of words carefully chosen. This line, among others, seems out of place in a collection charging toward refinement. So it’s not always the shortest pieces of every section that will leave you gasping for more air. Many sections are dominated by the second or third poem of the quartet. Perhaps the standout piece in the entire collection is the second poem of “Builder”:

You are tourniquet, a bound river. A wrist in sunrise with a dried keyhole. In the morning, you walk the river, watch the army rise from the grass, birds in formation, a warrant out on your pulse. You are shorn, you frighten the joggers, a day in your hand, wasps organized around your eyes with ropes. The creatures are building for you at the river, a daylight newspaper in the birdgrass. Balanced beautifully between narrative coherency and exquisite poetic images, this evokes just the right amount of the haunting undertones of Gwendolyn MacEwen, pointing back at the reader, thrusting us into a scene adjacent to mythology, mixing the everyday with the sublime. It’s here where Leslie is at her best.

While The Things I Heard About You does falter at times, wary of what it really wants to be, there is an energy behind the work that guides a promising ingenuity and imagination. The collection must be experienced at a distance to take in the girth of its intention, and simultaneously, each word must be examined to discover the text’s subtle idiosyncrasies. Leslie knows that not all poetic beauty can be rendered down to a single line. Each section has a clear standout in which Leslie’s keen sense of pacing and balance is clear. Her voice is confident, and her approach tactful. It’s in this maturity that she’s been able to embrace the tenant of writing that so many often fear, editing. But because of it, Leslie finds the perfect length for poetic breath by experimenting with all the options, and never retreats from the almighty writer’s mantra: smaller. |

JUSTIN LAUZON is a writer, poet, and reviewer born and raised in Oakville. Working out of Toronto, he is currently the Literary Coordinator for Toronto's Hear Here Salon and was the Literary Events Coordinator for Windup Bird Café . Most recently, Justin has founded Lexical.ca, Canada's most comprehensive online resource for writers and publishers. His work has been published in untethered Magazine and was a frequent contributor to Descant Magazine’s Blog. Follow him on twitter @JLauzonwrites.