A REVIEW OF AMBER MCMILLAN'S

WE CAN'T EVER DO THIS AGAIN

BY SHAZIA HAFIZ RAMJI

The Rusty Toque | Issue 8 | Reviews | Poetry | June 30, 2015

|

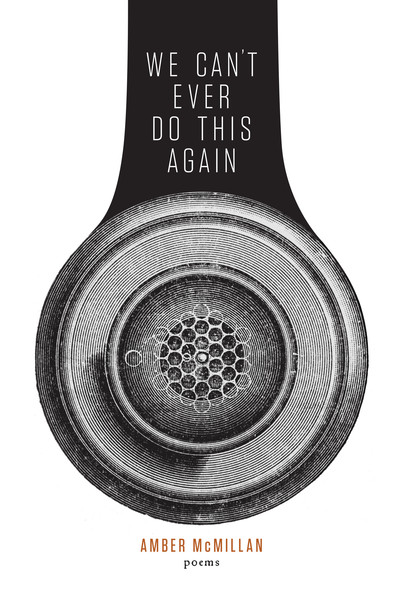

In the “Cover to Cover” feature for the March 2015 issue of Quill and Quire, designer Natalie Olsen discusses her struggle to create a cover for Amber McMillan’s debut book of poetry, We Can’t Ever Do This Again. Olsen says: “I still haven’t figured out why this collection of poems was so difficult. […] I realized a few things: I misconstrued the tone of what is actually a pretty dark and somber work; […] My solution was to simplify things.”

Olsen’s final judgment is spot on. We Can’t Ever Do This Again derives its strength not only from what is being said but from how it is being said. This defining subtlety is further energized by an intelligent and self-aware speaker who stresses the importance of the how--the tone. As well, Olsen’s decision to simplify is wholly in line with the tasks of McMillan’s poems that work toward confrontation, catharsis and acceptance. We Can’t Ever Do This Again is divided into four parts. The first half shapes a psychological landscape of taut interiority and silence, and is populated by family members and close friends. The second half moves outward into an engagement with grief and family history. The Agency of Imagination

|

SHAZIA HAFIZ RAMJI writes and edits in Vancouver. Her writing has been long-listed for inclusion in the Best Canadian Poetry anthology and has recently appeared in Frog Hollow Press’ Vancouver anthology, Lemon Hound, and Canadian Literature. She received the inaugural Yale Road Scholarship for The Writer’s Studio 2015 where she is pleased to be mentored by Meredith Quartermain, whose latest book is I, Bartleby.