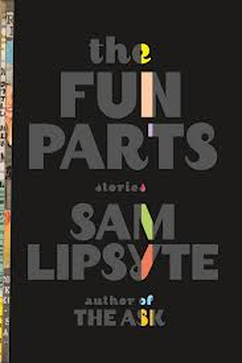

A REVIEW OF SAM LIPSYTE'S

THE FUN PARTS

BY DAVID HUEBERT

The Rusty Toque | Reviews | Issue 5 | November 15, 2013

DAVID HUEBERT is a PhD student in the English Department at The University of Western Ontario. His work has won the After Al Purdy Poetry Contest and appeared in journals such as Event, Existere, Matrix, Qwerty, Vallum, and The Literary Review of Canada. Recent work is forthcoming in The Antigonish Review, Grain, and CV2, and a first book of poetry is forthcoming from Guernica Editions.