A REVIEW OF REBECCA CAMPBELL'S

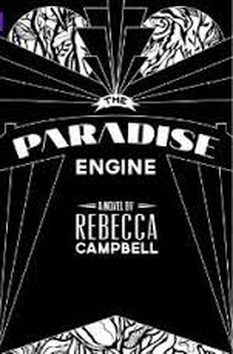

THE PARADISE ENGINE

BY JENNIFER QUIST

The Rusty Toque | Reviews | Issue 5 | November 15, 2013

JENNIFER QUIST's debut novel, Love Letters of the Angels of Death, was released in 2013 by Linda Leith Publishing. Based in central Alberta, she's a writer, poet, speaker, lapsed sociologist, and raiser of boys.