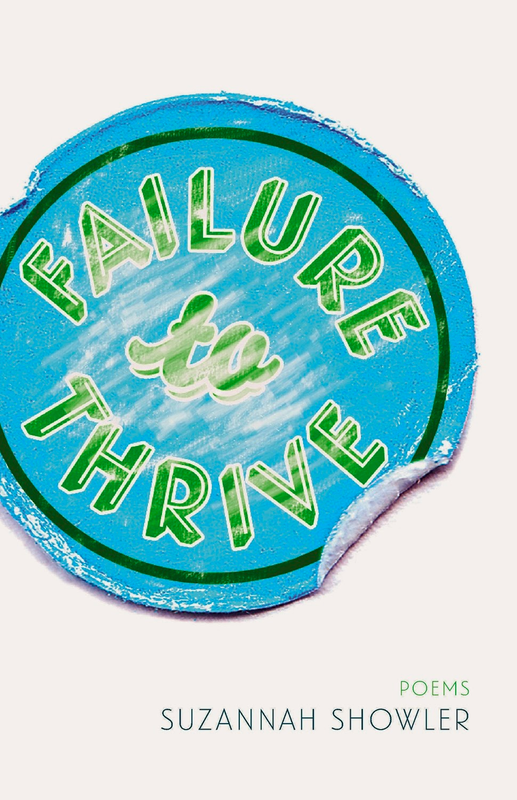

A REVIEW OF SUZANNAH SHOWLER'S

FAILURE TO THRIVE

BY KATERI LANTHIER

The Rusty Toque | Reviews | Poetry | Issue 7 | November 30, 2014

|

A quizzical voice rings insistently in the well-crafted poems of Suzannah Showler’s first collection, Failure to Thrive. The poems are at once sardonic and searching. It feels as if the poet is drawing us aside to ask, in a slightly self-mocking way, “Does all this add up?” Assertions are rapidly undercut by jokes. Philosophical musings must contend with intrusions by the quotidian, the mildly disgusting or absurd. The overall tone is one of bright melancholy. In tandem with resilient, even rambunctious humour, a restless intelligence is at work.

The intricacies of myriad surface textures and the sheer volume of stuff that surrounds us seem a preoccupation of these poems. Through a precision lens, Showler attempts to diagram this welter of detail in “The Reason,” the first poem in the book, which begins: Because you are the kind of person who It is easy to believe that the “you” of this poem “has a mantra (“there is too much of everything”)”, while at the same time detecting that the speaker has an ebullient interest in the too-muchness of what surrounds us. The poet veers frequently from descriptions of exterior surfaces, the challenges of perception and of simply trying to absorb and assess the evidence of the senses, to situating the self in a more abstract sense.“Sensory Anchors” is an apt title for the book’s first section, in which appears the finely observed poem “Pretty Good Time at the Olfactory Factory” with its vivid evocations of mainly unappealing smells: “Beach barbecue at low tide/ on the outskirts of a mid-sized city/ still flanked by industry// Cabbage sliced late at night/ with a steel knife. // Coconut-sweet wind laced with salt/ bending around the near-albino mesa/ of potash burped up out of the prairie.” Showler is adept at the conveying the passing shudder, as can be seen throughout the collection: “you reach into the viscera of a dust-green duffel”; “Look, I don’t have a strand in this hairball”; “like strung-out/ mulch at the bottom of a teacup.” She is a gleeful anatomizer of ick.

Tentativeness, a tendency to qualify or second-guess, is pushed to a comic extreme here, as can be seen in some of the titles: “Notes Towards Something Nearly Allegorical”; “One Possible Explanation for What Seems to Be the Case.” “The Reason” ends with a move that seem a signature one: “I take it all back.” And yet this poet can be also unflinching, as in “Why Don’t You Go Home and Cry about it?” from the sequence “Sucks to be You and Other True Taunts.” The poem begins with a grim scenario: “I have a feeling about a very slow/apocalypse where we are all drawn/ back to our hometowns by something/like a magnet that attracts whatever/inside us is most mediocre and true” and carries on to a graphic indictment of a lover’s loathsome tendency to describe the bodies of past lovers, then concludes with an amusing jab at Ottawa. The quick shift of registers and direction is surprising, deft and one of Showler’s strengths. The influence of Karen Solie can be seen in the self-questioning and bits of advice-to-self, which surface often. Take these lines from Solie’s “Mirror” (from Modern and Normal): “Evade your eye. Try to see as others do/ what is desired or refused. What went wrong./ Or right, then wrong. Objectively, what hangs. / Pull yourself together. You are neither kind/ Nor cruel. You drag on. The girl is gone./ Consider that it might be time to call in/ a professional.” Then consider these from Showler’s “Already Today You Have had Several Good Ideas”: “The film of resistance/ you’re wrapped up in:/ it’s mainly your own dead cells,/ the stuff that turns up under your nails/after scratching at the remains/of wounds accrued or conjured.// Once you start in that way,/ it’s pretty hard to stop.// Better to just wait it out, look at things.” Like Solie, Showler has a fondness for the found poem and the list poem. “Fun with Counterfactual Conditionals!” is an alternately entertaining and chilling variation on a list poem: “If there hadn’t been a condom-thin layer of ice on the road at the bottom of the bridge at the end of April// If you had invested in real estate// if you’d had a taste for spicy foods// If you’d drunk a box of wine// If you’d mentioned when you were seventeen you’d unsuccessfully attempted to hang yourself.” “Thirteen Subcategories,” in the first section, is both “list” and “found”: “Accidental deaths by location/ Victims of aviation accidents or incidents/ Accidental deaths by electrocution/ Accidental deaths by falls.” This might be thirteen ways of looking at a Google search but it leaves one wanting more—more twists or an element of artistry. While “Jeopardy,” with its evocative hanging answer-questions: "Where is the origin of the problem?/ What is authentic evidence of some unlikely thing?// What is nostalgia for something that never occurred?/ Where is the best place to hide evidence of wrongdoing?/ What is the direction in which we are currently headed?” is a rather more successful example of a found poem than "Thirteen Subcategories," it might be advisable for poets in the early stages of their writing life (or any stage) to consider the limits of this form. Perhaps this reviewer has simply read her quota of them, but it starts to seem as if the found poem, and its near-relation, which one could call the “research” poem--is a too-convenient way of demonstrating a literary eye and filling out a collection. (To take another recent example, the long prose poem “The Art of Plumbing” in Brecken Hancock’s impressive debut collection, Broom Broom, has its high points and connects thematically with the book. But while the snippets of history in it are fascinating, they have their longueurs. The poem lacks the fiery intensity of the two knockout poems that follow, “Evil Brecken” and “Once More”). When found material is a starting point, rather than an end in itself, poets show us their art. Showler’s playful philosophizing reaches its peak in “Bracketing Paradox”, which is quite a charmer: “It’s like if you had a thought/ that grew too large for its quarters, too much/ to bear up, and it needed to move out, find a job/ look for real estate/ start putting itself out there/ stop putting things on hold.” One could see the influence of Kevin Connolly’s mordant humour in Showler’s sensibility (just put Connolly’s “Audition Piece” from Revolver and Showler’s “Position: Monster” side by side) and yet Showler is perhaps more sly and slippery, a touch more mercurial. One of the strongest poems in the book is the eleven-line “Notes Towards Something Nearly Allegorical,” which ends: “Glass never forgets how it began: viscous, easily blown open.” This line delivers a satisfying resolution to the brief poem and stands well on its own, in contrast to the rather flat one-line section in “A Short History of the Visible”: “Glass. It’s important to mention glass.” One could argue that the latter is funny, but perhaps it isn’t quite funny enough. At her best, Showler gives us stand-up with a searching glance: “I’m pretty sure this guy I know is faking/ imposter syndrome.” Showler shines in the first-person “Confessions from the Driver of the Google Street View Car.” Here, as in other poems, she mixes realistic-sounding speech with poetic flourishes. The dry wit of the ending is nicely judged: “In the end, it won’t be them, exactly./ (Privacy protection is paramount, they told us.)/ A computer fixes each pedestrian face/ into a pixillated hash./ You might not even know yourself.// So, where do you live?/ I’ve driven lots of places.” One could wish more lines had the rhythm and assonance of these from “Remote Sharing”: “…now you’re roving the low// country in a PT Cruiser, ego/ bloating like a sourdough starter.” In general, a coaxing-out of music would be desirable to counterbalance the prose-y talkativeness. Showler shares this tendency with one of her mentors, Ken Babstock. Discursive chattiness can lead to confusing eddies or stall a poem in a cul-de-sac. Both poets are fun to get lost with, but perhaps this tangential tendency should be curbed more often to bring greater intensity and focus to individual poems. (Babstock has achieved this in the surveillance-station sonnets of his most recent collection, On Malice. It’s exciting to see how the discipline of the shorter form heightens the drama in them—no dodging and feinting or overwhelming with detail.) Randomness is an undeniable part of life, especially life lived online. Showler captures this well in the series of non-sequiturs that make up “Keep Scrolling”: “A three-legged dog chasing down a ball,/ pumping forward like a skier going over moguls// burnt calcium, knots where rocks/ erode a river/ time-lapse photograph/ of fireflies, misguided vacation purchase…// triptych of Nicolas Cage portraits/on black velvet, a model of/Euro Disney made to scale…” We hardly need to be told it’s in the realm of: “and so on/and so forth…” In an otherwise well-edited book, this is a rare instance of over-playing an ending. Failure to Thrive is an accomplished first book. The ominous title (a chilling one to any parent familiar with the term), is, in the end, both funny and a characteristically over-modest assessment. According to my diagnosis, this newborn is thriving. |

KATERI LANTHIER's work has appeared in numerous journals, including Green Mountains Review, Hazlitt, Great Lakes Review, Leveler and Best Canadian Poetry 2014. She was awarded the 2013 Walrus Poetry Prize. Her first book of poems is Reporting from Night (Iguana, 2011). Her new collection is forthcoming from Signal Editions, Véhicule Press.