THE WRITER TAKES SHAPE:

A REVIEW OF SHASHI BHAT'S

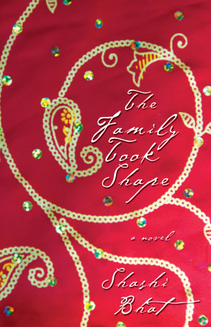

THE FAMILY TOOK SHAPE

BY LEE SHEPPARD

The Rusty Toque | Reviews | Issue 5 | November 15, 2013

LEE SHEPPARD is a writer, a

contributing editor of the literary magazine Pilot and a teacher at West End Alternative Secondary School in

Toronto where he has developed and currently teaches two project-based courses:

ReelLit a film-studies and video

production program and The West Enders,

a creative writing and illustrating program that produces an eponymous

illustrated literary journal.