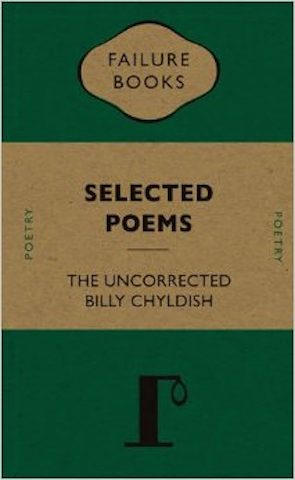

A REVIEW OF BILLY CHILDISH'S

SELECTED POEMS:

THE UNCORRECTED BILLY CHILDISH

BY ROSEMARY RICHINGS

The Rusty Toque | Reviews | Poetry | Issue 7 | November 30, 2014

|

Selected Poems: The Uncorrected Billy Chyldish, published 2010, does exactly what the title promises: it remains uncorrected and filled with unorthodox spelling and line breaks. Billy Childish’s choice to publish his poetry unedited has a surprisingly positive effect: it makes the content raw and uncensored. It’s autobiographical and contains spoken word/Rock n’ Roll, rhythmic conventions and is subdivided into sections about family, love and sex, animal and human nature, abuse, and the artist lifestyle. Billy Childish is a Dyslexic, Punk poet, painter, and musician. The anthology celebrates oddity, while reminding readers of the harsh consequences that come with being odd.

The first section, Insects And Small Crawlers celebrates creepy crawlies. What makes Childish’s nature poetry different than most is the following: his subjects aren’t a source of conventional beauty, metaphor, or personification; they’re a genuine reflection of fear, fascination, and self-reflection. A highlight is the first poem of the anthology, The Little Brave Ant, where the poet drinks beer and admires an ant’s bravery while the ant drinks a puddle of his spilt beer. The Little Brave Ant is a Punk reincarnation of John Donne’s The Flea, where the object of desire is the idea of drinking and merriment. Section two, Beasts begins less effectively with Some Kind Of Living and The Dog, which depict the not so flattering aspects of cat and dog instinct in an inconclusive and meaningless fashion. The Zoo is the highlight of the Beasts section. It describes the poet’s experiences visiting a local zoo, while humans passively watch the sexual activity of caged animals. The Zoo builds like a perfectly constructed joke, from observational commentary on animal sexual activity to a venomous concluding image that holds a mirror in front of the poet, humanity as a whole, and the reader: “I felt foolish being there/staring dumbly with the crowds/sucking on our ice creams”. The Love and Sex Section of the anthology was the one I found more difficult to finish because many of the poems are meandering rants about ex-girlfriends and sexual encounters that are too intimate to connect with readers. She Got It Up In The Air, 15 Quid, and No Reason have a fly on a wall effect, where the reader is the reluctant observer, watching from a distance the private lives of strangers that they’re not supposed to see. The anthology’s highlight is Chatham Town Welcomes Desperate Men, a poem about Childish’s hometown, which celebrates the everyday lives of the poor, the working class, and the oddballs of society. The poem successfully makes Chatham familiar to the reader, through constructing a nursery rhyme like rhythm, that names all the different groups that are welcome in the community. Chatham Town Welcomes Desperate Men is one of two poems in the anthology that focuses on celebrating eccentricity. In the Abuse and Forgiveness section there’s a poem called I Give Myself To Them All that describes social outcasts that Billy Childish has met in the bars while inviting them to be his companion and subject of his poetry. Both poems use a marching band staccato to invite social misfits, that don’t typically read poetry (and are rarely subjects of poetry) to celebrate their identity, read Childish’s work, and allow Childish to be a mouthpiece for their experiences and struggles. These two poems are the anthology’s glue that helps the reader understand the purpose of Childish’s poetic observations on the absurd aspects of human, insect, and animal instinct. The Abuse and Forgiveness section is a dense read that’s another highlight. The poems are intensely intimate, confessional, and rival Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton’s thoughtful, dense darkness. The section begins and ends with a cohesive, perfect unison A Mad Noise Like Birds and Bed Wetter, which perfectly parallel each other because the section begins with a poem that discusses the effect of the abuse: the poet’s regret about abusing their former lover, and the cause of the abuse: their role as a former victim. The Abuse and Forgiveness section successfully implicates the reader to become an active participant. Each poem is a poetic monologue where the reader becomes Childish’s former abusers, lovers, and friends, gathered in a quiet, intimate setting so that they can have a secret whispered in their ear. The intimate confessional quality that’s present in the Abuse and Forgiveness section is at its most effective in Poisonous Women, where Childish describes the poisonous relationships he’s had with women who are unable to love: “abused by your fathers/and thumbling men/mirroring my own/trampled heart.” Fathers and Sons is a perfect follow up to the Abuse and Forgiveness section. The memories of abuse smoothly transition to Childish’s poetry about his father and his son Huddie. The section begins with a poem about Billy Childish’s father, which describes a troubled misfit, a lot like the social outcasts that Childish celebrates and welcomes in Chatham Town Welcomes Desperate Men: “my father was a failer/my father was a criminal/my father was unhappy/my father was a mad man.” Unlike Childish’s Chatham Town Welcomes Desperate Men the father’s behavior isn’t a source of celebration but anger, physical violence, and a grotesque, concluding image of the father’s bruise, which Childish compares to a purple slug. This poem functions as the Fathers and Sons section’s unifying force that helps the reader understand Childish’s idealized portrayal of his son, Huddie. Primary School Tough took a few reads to appreciate and is an out of place addition to the Abuse and Forgiveness section. It begins with an image that paints a vivid picture of Childish’s memory: “there was frost on the tarmac/that December morning/and my cap was pillarbox red.” Although the imagery in the opening stanza is ripe with visual appeal the final stanza leaves the reader with a sensation of being excluded from an inside joke. This poem has the same fly on the wall distancing effect as many of the poems featured in the anthology’s Love and Sex section. A crucial contribution and highlight of Fathers And Sons are the poems about Childish’s son, Huddie. Every poem featuring Huddie transforms Childish into a willing participant in a child’s game. In Huddie 8.12.99, Huddie is described as a child that came into the world to teach his father love that’s also a pastoral figure. In The Man Who Thought He’d Never Be A Father Is A Father Huddie is depicted as an angelic figure surrounded by a golden light. Huddie is a crucial figure in Childish’s poetry that enlightens the poet’s worldview. The In Nature section begins in a way that contradicts the anthology’s celebration of grotesque human and animal nature. Although Fat Nature meanders in a circular direction it sets up the section’s dominant tone of anger towards nature’s effect on others. It also cleverly deflates the romanticized perspective on nature that’s commonplace in poetry. In Fat Nature Childish lists the grotesque and cruel parts of nature while reminding the reader that nature isn’t always beautiful and delicate. Fat Nature smoothly transitions into Poem, where Childish reminds the reader that something as simple as a Kleenex is often better than a delicate rose. In very few words the poem makes the reader question the value of non-practical objects with no other purpose beyond conventional beauty. The With And Without God section focuses on the horror and beauty of human nature both in Childish’s life and in the lives of strangers he passes on a daily basis. Childish excels at depicting the horror that humans are capable of and experience on a daily basis an overwhelming level of honesty and complexity. The most vivid, memorable example of Billy Childish’s complex honesty towards human nature is the section’s first poem, Old Woman Downtown, where Childish describes a homeless woman as: “wite face n purple lips/with some bloke snogging her/blowing life in or out”. Childish’s perspective on a homeless stranger is neither an attempt at pity nor a didactic verse on consequence, it’s a cold dose of reality, where the reader is taken by the hand and shown human nature’s follies that people try to ignore. In the anthology’s final section, Emotional Secretions, the final stanza of the poem, I am The Uncorrected accurately summarizes what it’s like to read Billy Childish’s poetry: “I/am gloryiously/ un corrected/ and will/be coming for you/next.” Although some of the poems featured in the anthology move in a repetitive circle, bordering on oblivion, Childish’s uncensored, unedited, fearless approach to poetry is a refreshing addition to the contemporary poetry landscape. |

ROSEMARY RICHINGS is

a freelance, Toronto based writer and blogger who has been actively freelancing

since she graduated from university back in June 2014. She’s written articles for Adone Magazine,

Trueblue Magazine, Fame Culture Blog, and is trying to score an interview with

Archie Comic CEO John Goldwater for a blog entry she was asked to write for

Bitch Magazine’s blog. Her review in the latest issue of The Rusty Toque is her

first published book review. Two other book reviews will be featured in

upcoming issues of Public Arts Journal and Winnipeg Review Of Books. In the summer of 2014 her first published

poem appeared in Estuary Literary Magazine and she is working on a poetry

anthology called “Then He Held Out His Hand”, that she’s submitting to the 2015

Robert Kroetsch Award For Innovative Poetry. She’s done readings and

performances of her poetry at Paprika Festival, New Waves Arts Festival,

Smashmouth, BAM Youth Slam, and various open mics and poetry slams in her

community. She also does freelance blogging and writing work for local, small

businesses, and Not For Profit Organizations. Her blog is www.rosiewritingspace.ca.