SPECIAL FEATURE:

AN EXCERPT FROM JOHN PAIZS'S "CRIME WAVE"

BY JONATHAN BALL

The Rusty Toque | Special Feature | Film Essay | February 20, 2014

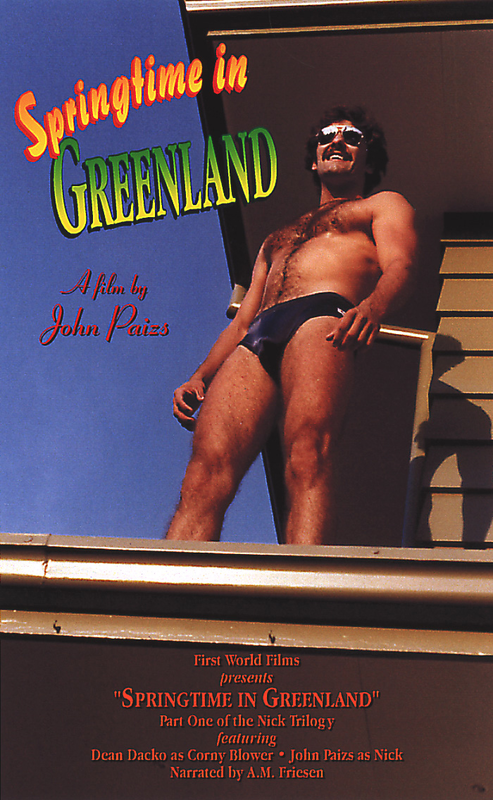

JONATHAN BALL ON "SPRINGTIME IN GREENLAND (1981)"

|

"Springtime in Greeland (1981)," an excerpt from John Paizs’s “Crime Wave” (University of Toronto Press, 2014).

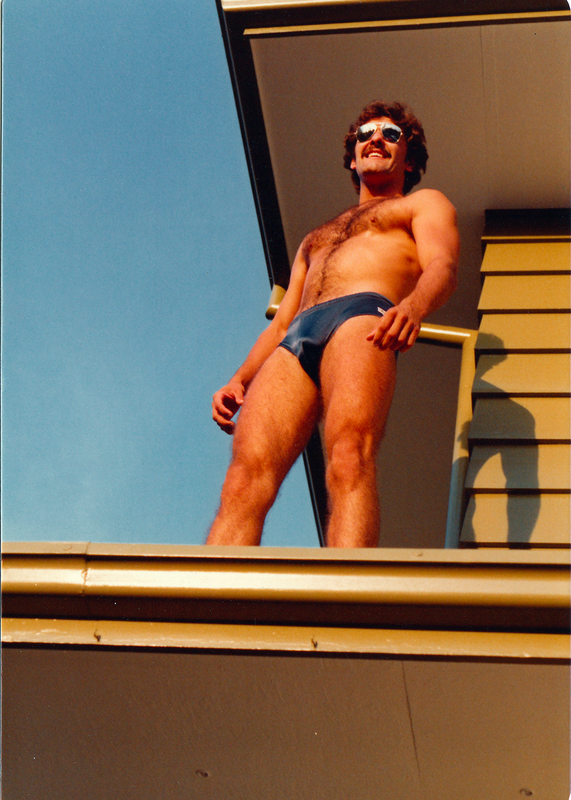

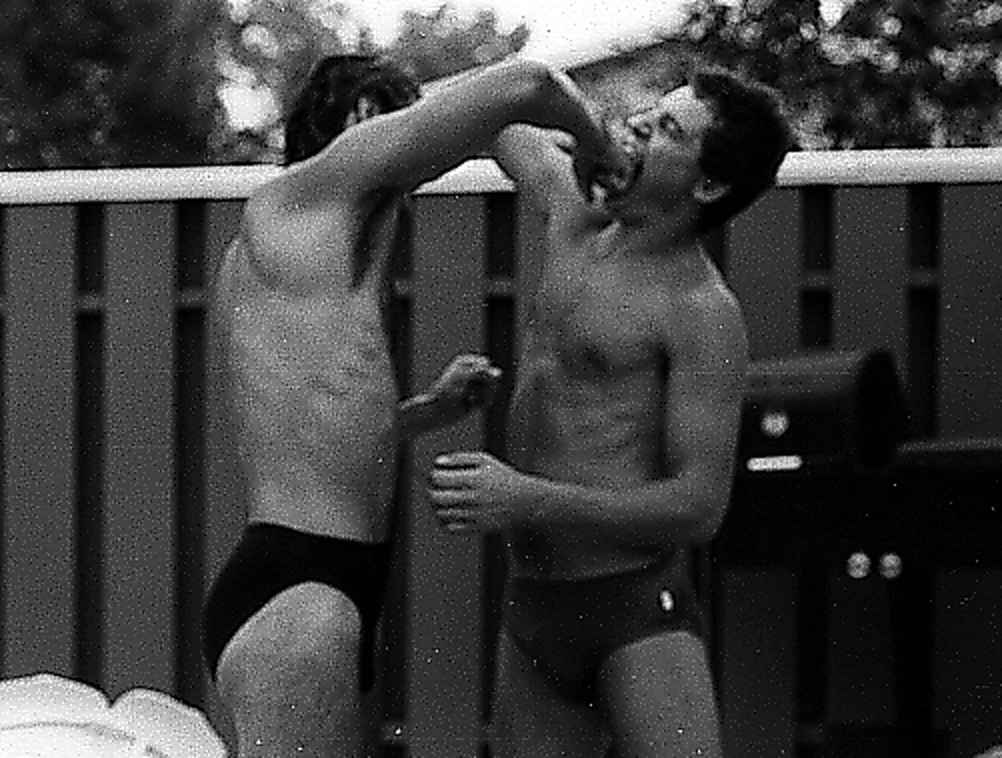

In Paizs’s next film, Springtime in Greenland, he again plays the “quiet man,” now named Nick after Hemingway’s alter ego in his coming-of-age stories. Nick appears in three films, later screened together as the feature-length program The Three Worlds of Nick. Paizs has stated that “[I] always meant [these films] to be a trilogy–a feature, actually, that I could finance and make in manageable stages.”[1] Each film announces itself as part of a larger series, through opening title cards: in order, they read “The First World … Nick at home” (Springtime in Greenland), “The Second World … Nick learns something” (Oak, Ivy, and Other Dead Elms) and “The Third World … Nick finds love” (The International Style). The Three Worlds of Nick might be considered Paizs’s avant-garde feature film debut, and deserves rediscovery as much as Crime Wave. Beginning similarly in a documentary style, Springtime first differs from Obsession through its third-party narrator (and his bizarre intonations). Unlike Billy Botski, Springtime’s narrator is not also a character in the film, and he has no special access to Nick’s interior world of thoughts and feelings. This development separates the viewer from the silent Paizs character, to hide Nick’s inner life. The creation and refinement of the “quiet man” character, who appears in various incarnations across Paizs’s five 1980s films, marks these works as particularly postmodern through the figure’s ironic anachronism, intertextual transformations, and destabilizing presence. At first, playing the protagonist of his own films was a matter of necessity for Paizs: because he could only shoot erratically due to his schedule and finances, Paizs cast himself as a lead actor who could be available whenever he was, at a moment’s notice, without pay. The character’s silence developed pragmatically: because Paizs didn’t like his voice and didn’t think he could act, he decided on silence and blank expressions.[2] Although initially a matter of convenience, Paizs’s manner of building films around his own on-screen appearance, as a figure who is marked and isolated by silence and blankness, has distinctive postmodern qualities. In McHale’s terms, “the fictional world now acquires a visible marker” of its created status due “to the artist’s paradoxical self-representation.”[3] Although in the films Paizs presents himself as “Nick” and not as an author-figure (a distinction that collapses in Crime Wave), by appearing as “Nick” in a mannered way that marks his appearance as artificial and performative, Paizs draws attention to his performance as performance. Thus, as with the self-presence of the author, “the artwork itself comes to be presented as an artwork.”[4] However, Paizs always seeming to be Paizs yet never claiming to be Paizs allows the film’s narrative world to retain a certain stability despite the auteur’s destabilizing presence. The “quiet man” figure becomes all the more strange through his transmutations from film to film (all differing in their styles and genres) and name to name (from Billy to Nick to Steven). Thus Paizs’s 1980s films allude to one another as they signal their own artifice. Discrete and self-contained, while also parts of a larger set, Paizs’s “quiet man” films draw attention to Paizs’s own status as author of their filmed worlds. Paizs has incorporated, alongside elements from popular culture, elements from his own productions–even his own self (a gesture that suggests the unnatural nature of the postmodern self). Yet unlike most similar postmodern appearances of the author, Paizs does not draw the audience close in a demystification of narrative processes (something Paizs later does in Crime Wave); rather, he uses his own body to further inscribe emotional distance. Nick, as acted blankly by Paizs, is unknowable. When narration appears, or other characters speak directly to (or of) Nick, it does not serve to enlighten us. Others have no insight into Nick’s character, and the viewer’s position lacks privileged access to Nick’s private moments. The resulting figure serves as a screen upon which the audience can project Nick’s imagined personality (like the fantasy space of the cinema screen itself), yet they cannot identify with Nick since Paizs refuses to affirm any such projections. Nick (like, later, Steven Penny) seems fated, therefore, to become a social outcast. This misfit position is supported in formal terms through the anachronism of the “quiet man” character. Nick’s underdog or outsider status does not make him lovable by default. He appears self-conscious, even haughty, and his victimization seems at once deplorable and appropriate. Nick’s antagonist in Springtime is Corny Blower, who, Cagle observes, “like ‘Connie’ in Obsession, is a collection of gender stereotypes.”[5] Nick is cheated and teased by the brutish Corny in a backyard diving competition, and instigates a fistfight. We may not be surprised at Nick’s violent lashing out, and may even sympathize with him in this moment. But afterwards, when all have gone home, Nick remains: crouched over the pool in the night, pulling black water onto his face like something inhuman (hardly a figure with whom we’re asked to identify), some primal creature at the edge of the ocean from which it just crawled. Springtime is notable for its unusual structure, which falls into five rough acts. The first “act” is styled like a documentary about the bucolic suburb of Greenland, with Nick and his family introduced by a drawling, erratic narrator. In what we might consider a second act, the documentary and its narration give way to a disturbing night scene styled more cinematically. Nick awakens during a thunderstorm and steps out on the front lawn. Inscrutable in his motivations, Nick stares at his family’s home from the outside (perhaps to confirm his outsider status). As if unable to bear Nick’s scrutiny, the film escapes to a third act, this time a bizarre commercial sequence during which a new narrator trumpets the technological wonders offered by “The House of Tomorrow.” Springtime returns, in its fourth act, to the pool party and its masculine competition between Corny and Nick. After the fallout of their brief brawl, a fifth act provides a coda, as our first drawling narrator returns to celebrate Greenland’s spring parade (which Nick skips, although his dog settles in for the spectacle). Springtime’s structural symmetry confirms the central position of the “House of Tomorrow” segment and its consumerist ideology. At the film’s heart lies the commercial “The House of Tomorrow,” nestled between two cinematic sequences about Nick; in turn, all of this is framed between two documentary sequences about Greenland. Cagle notes that this commercial “segment is an exact replica, played with deadpan earnestness, of countless promotional films aimed at housewives and newlyweds. The message of these short subjects was as unvarying as it was clear: domestic bliss can be attained only through conspicuous consumption.”[6] Thus, in copying the style of commercials and promotional films, Paizs also reproduces their ideological assumptions. When decontextualized in this way, these assumptions are laid bare and their absurdity is plain to see: an implicit critique develops through ironic appropriation of these surfaces. Yet Paizs seems, at the same time, to love these surfaces. He copies their style in imitation rather than copying the original texts whole–for example, instead of stitching together already existing clips in the manner of films like The Atomic Cafe (1982). Copying in The Atomic Cafe manifests itself in ironic montages of American propaganda films, assembled to present a nuclear attack on the United States: the implication is that the logical terminus of militaristic foreign policy is boomerang-style annihilation. Paizs’s approach, although it still fuses irony with critical undertones, is less biting, less directly political, and more ambivalent. “The House of Tomorrow” segment features a much more vibrant narrator than the first segment of Springtime, and this second narrator (Douglas Syms) will later return to lead us through the beginnings and endings of Steven Penny’s failed screenplay in Crime Wave. Neil Lawrie, the actor playing the patriarch of this “House of Tomorrow,” will also return in Crime Wave as the deranged serial sex murderer Dr C. Jolly. Connecting the two figures, or even considering them identical, seems a tempting although radical reading, given Paizs’s other metafictional games and the pathology that informs this commercial segment. The viewer cannot possibly be as excited about “The House of Tomorrow” as the characters in the film, who orgasmically respond to banalities like thermostats, electric lights, toasters, and lawn sprinklers. Lawrie’s appearance in Springtime as proud patriarch of a consumerist paradise, and his reappearance in Crime Wave as the murderous Dr Jolly, suggest a natural evolution from one figure into the other, although little in Crime Wave connects Dr Jolly to consumer culture. However, Jolly does lure his victims by claiming to be a Hollywood script doctor, and thus he serves as a stitch that sutures Crime Wave’s thematic obsession with violence to the capitalist ambitions and colonial reach of the American cinema. Without explanation or context, “The House of Tomorrow” segment prefigures (in its tone of deadpan irony) the sketch comedy of The Kids in the Hall, a show for which Paizs later directed. This “House of Tomorrow” commercial, not unlike the angular plots of sketch comedy, seems like a digression more than a progression, in that it has no explicit connection to Greenland or Nick. However, as Pevere has written, the commercial segment “effectively provides a kind of pop-ideology context for the absurd middle-class melodrama being played out around the sun-baked backyard barbecue … A dialectic of sorts is established between the expository mock-documentary passages and the poolside showdown that effectively suggests a cause-and-effect relationship between them: mindless media messages make for mindless behaviour.”[7] Pevere’s insight is apt but fails to account for the structural symmetry of Springtime and its two levels of mock-documentary (the erratic narration concerning suburban Greenland, which opens and closes the film, and the earnest narration concerning “The House of Tomorrow”). It is not simply that media messages have distorted reality: reality itself is coextensive with media fantasy. In the world of Springtime, it is senseless to seek cause-and-effect relationships between suburban reality and commercial fantasy. One does not produce the other, to then feed back in a series of dialectic exchanges. In his analysis, Pevere argues that only in the later Nick films does this “distinction between the world of the drama and the world perpetrated in and by the media”[8] collapse. However, as the pseudo-documentary frame of the opening and closing segments makes clear, this distinction has already suffered a postmodern collapse in Springtime, where suburban “reality” is itself a commercial fantasy. The framing narration attempts to sell us on the virtues of Springtime in Greenland, as if Springtime as a whole were a promotional film for suburban development. That is, a commercial housing another commercial, since within just such a middle-class milieu we find “The House of Tomorrow” (although most of the story’s action takes place outdoors, around the backyard pool, and no significant attempt is made to suggest that Nick’s house is a technological wonder). The only person who isn’t convinced of these values, who isn’t buying (at least, not yet), is Nick. However, in The International Style, the final Nick film, a coda reveals that Nick has retired from international spydom to a quiet domestic life in Greenland. He stands in the place of his father, by the backyard pool that was the site of his clash with Corny–now assimilated into the new world order. His new wife and baby sit nearby. Nick’s face is expressive, for once, contorted in discomfort as he struggles to light the barbecue. [1] Robert L. Cagle, “Persistence of Vision: The Wonderful World of John Paizs,” Cineaction 57 (2002): 46. [2] BRAVO, On Screen! Episode devoted to Crime Wave, BRAVO, 16 March 2008. [3] Brian McHale, Postmodernist Fiction (New York: Methuen, 1987), 30. [4] Ibid., 30. [5] Cagle, “Persistence of Vision,” 46. [6] Ibid., 46. [7] Geoff Pevere, “Prairie Postmodern: An Introduction to the Mind & Films of John Paizs,” Cinema Canada (1985): 13. [8] Ibid., 13. |

John Paizs's "Crime Wave"

By Jonathan Ball

Canadian Cinema

University of Toronto Press

Scholarly Publishing Division (2014)

Description from University of Toronto Press

John Paizs’s "Crime Wave" examines the Winnipeg filmmaker’s 1985 cult film as an important example of early postmodern cinema and as a significant precursor to subsequent postmodern blockbusters, including the much later Hollywood film Adaptation. Crime Wave’s comic plot is simple: aspiring screenwriter Steven Penny, played by Paizs, finds himself able to write only the beginnings and endings of his scripts, but never (as he puts it) “the stuff in-between.” Penny is the classic writer suffering from writer’s block, but the viewer sees him as the (anti)hero in a film told through stylistic parody of 1940s and 50s B-movies, TV sitcoms, and educational films.

In John Paizs’s "Crime Wave," writer and filmmaker Jonathan Ball offers the first book-length study of this curious Canadian film, which self-consciously establishes itself simultaneously as following, but standing apart from, American cinematic and television conventions. Paizs’s own story mirrors that of Steven Penny: both find themselves at once drawn to American culture and wanting to subvert its dominance. Exploring Paizs’s postmodern aesthetic and his use of pastiche as a cinematic technique, Ball establishes Crime Wave as an overlooked but important cult classic.

By Jonathan Ball

Canadian Cinema

University of Toronto Press

Scholarly Publishing Division (2014)

Description from University of Toronto Press

John Paizs’s "Crime Wave" examines the Winnipeg filmmaker’s 1985 cult film as an important example of early postmodern cinema and as a significant precursor to subsequent postmodern blockbusters, including the much later Hollywood film Adaptation. Crime Wave’s comic plot is simple: aspiring screenwriter Steven Penny, played by Paizs, finds himself able to write only the beginnings and endings of his scripts, but never (as he puts it) “the stuff in-between.” Penny is the classic writer suffering from writer’s block, but the viewer sees him as the (anti)hero in a film told through stylistic parody of 1940s and 50s B-movies, TV sitcoms, and educational films.

In John Paizs’s "Crime Wave," writer and filmmaker Jonathan Ball offers the first book-length study of this curious Canadian film, which self-consciously establishes itself simultaneously as following, but standing apart from, American cinematic and television conventions. Paizs’s own story mirrors that of Steven Penny: both find themselves at once drawn to American culture and wanting to subvert its dominance. Exploring Paizs’s postmodern aesthetic and his use of pastiche as a cinematic technique, Ball establishes Crime Wave as an overlooked but important cult classic.

Jonathan Ball

Jonathan Ball Photo by Mandy Heyens

JONATHAN BALL holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Calgary, and is the author of four books: Ex Machina (BookThug, 2009) considers the relationship between humans, books, and machines; Clockfire (Coach House Books, 2010) contains 77 plays that would be impossible to produce; The Politics of Knives (Coach House Books, 2012, and winner of a Manitoba Book Award) explores the violence of language, narrative, and spectatorship; and John Paizs’s “Crime Wave” (University of Toronto Press, 2014) examines the 1985 cult film classic as an important example of early postmodern Canadian cinema.