SPECIAL FEATURE:

AN EXCERPT FROM

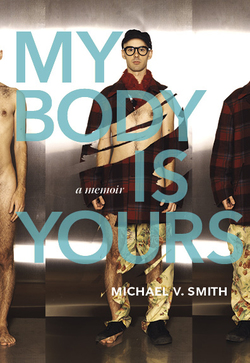

MY BODY IS YOURS: A MEMOIR

BY MICHAEL V. SMITH

The Rusty Toque | Special Feature | Memoir | June 9, 2015

Excerpt from My Body is Yours: A Memoir

THE OMG OF OCDLesson #4: It’s never a bad idea to be completely honest about the facts.

- Alan Downs, The Velvet Rage Compulsion is a mild form of temporary lobotomy. Sexual compulsion is a lobotomy with orgasms. When the machinery of sexual compulsion is turned on, part of the brain shuts off. Like a blind person leaning against a touchpad light switch, you don’t even know you’ve hit it. As the body turns on, the critical rational brain dims.

Sometime in my early thirties I swapped out cruising the park for surfing online sites, because at least with the latter, there was some conversation beforehand and a means to contact tricks afterwards, provided they hadn’t deleted their profile. Those automatic nights at the keyboard, I surfed porn for at least an hour, usually an average of about three, masturbating. At the same time I’d be on two other websites for hooking up, one with a chat room and one with a list of other users near me who were also online. I could have my cam on in a room, watching a half dozen other folks masturbating. I could be chatting in private windows with a handful of men, jerking off on cam, obviously, plus cruising porn, plus texting someone local that I might have happened onto, plus browsing new profiles as people logged on. In more recent years I’d also be on two different GPS-based apps on my phone, like homing devices for gay guys. Altogether, they made a great immersive distraction, way better than TV. I could have eight or more different options running at once. Vibrant, interactive channel surfing. A mediated frenzy. When really focussed, I could hit the refresh button over and again, about forty times a minute, waiting for a new profile to materialize at the top of a list when a user came online. I might spend most of two hours doing nothing more than that. I could take short breaks to read a profile, or watch some porn, but would be quickly back to checking for new log-ons. I got to know the other compulsive users well, so that if they created a new profile I’d likely recognize them by their height-weight statistics (they often logged differing ages) and their collection of interests. Rarely was someone online any given night that I didn’t already ‘know’. Obviously, if it was rare to find someone new, the chat you find on cruising sites, and the too-familiar profiles found there, are beyond boring. Compulsion is not sustained by novelty, but by its ability to turn off the conscious mind, to distract. The less you have to think, the more automatic, the easier it is to disengage from the present. Having a dozen different sites going at once doesn’t offer the new, but just enough distraction to work. Ninety-nine percent of all my chat conversations were routine and predictable. We shared statistics of height, weight, dick length, sometimes girth (idiosyncratic, I guess, considering everything else I got up to, but girth just seemed like overkill), age, sexual interests, and, for the sophisticates, hair and eye colour. I often changed profiles in that time, or I’d have two different sessions going using my other profile. I kept one that was more a dating lure and one for sex (which had consistently more bites). Eventually in the evening it got late enough and I’d been masturbating long enough that I’d give up on being fussy and agree to meet some guy who didn’t want to kiss, or had a wife, or didn’t like condoms but wrote that he only wanted oral (which was in theory, not practice). We’d meet at my place, or in the small lot of a cemetery, or a dog park, a bird sanctuary, alongside the highway at a specific intersection, under a bridge, beside a building, in an alley, in his truck, in a parking lot of a fruit packing plant, in the park beside his house, or, on rare days, at his place, if the family/roommate/parents were out of town. One single-parent father used to invite me over while his fifteen-year-old son slept upstairs, but that just weirded me out. Anyone who says you have to be quiet when you come over should raise flags. Save yourself trouble and always decline. On the best nights, the hottest nights, from the moment I signed off with a rendezvous until we met up, my body trembled. It was an odd mix of deliciousness and fear, like licking the sugar off a witch’s cabin in the woods. Yummy, with a pound of peril in the recipe. (My best friend Colin had a similar experience when he was acting out. “My trembling was more like walking towards the guillotine and pretending it wasn’t there,” he told me, which is also apt. The fear made the thrill more thrilling, and the automaton more necessary.) My legs would shake like I’d run a marathon in heels; they felt barely able to hold me up. My hands were late Katherine Hepburn. My arms, Jell-O. Even my stomach felt strapped into a body vibrator, shaking the cellulite. Sometimes my teeth rattled so hard my jaw began to hurt. Much of the compulsion was in response to stress, obviously. The more stress, the deeper I wanted to slip inside the automaton. They were proportionate. If you know anything about addiction you likely understand the perfect loop of compulsion, a snake swallowing its tail—the stress of fucking up from acting out causes you to want to act out. The more you screw up because you disappeared, the more you need to disappear again. The more sleep you lost last night the more likely you are to lose sleep tonight too. Compulsion has long been a means to cope with a fucked up life. Gary The Therapist tells me that you can’t get rid of your compulsive lizard-brain, but you can choose which things you get compulsive about—the lizard won’t disappear but it can be channelled. Into writing, for example, or playing board games, or sport, or crafting. When I was young, it was reading. I could stick my nose in a book for an entire morning, afternoon, and night, preoccupied with finishing. Nothing could penetrate that imaginary world—the parents disappeared, the chainsaw next door, the slamming doors, my sister calling my name or the phone ringing, all gone. I read two or three books a week, on top of doing schoolwork. When I was done reading my books I read my sister’s next, two grades ahead. TV used to disappear me too. You could try talking to me when a good drama was playing, but you’d be lucky if I noticed you’d walked into the room, let alone spoke. My attention has always had the potential to be immersive. It’s a great device for finishing novels. It can really help put you ahead of the pack at work. It means you rarely lose things, because you tear the house apart five or six times until you find it. In my early years as an adult, compulsion wasn’t much of a problem. I poured my attention into school and books. Dana and I lived together for two years, then I lived with Paul. But when I stopped drinking, I kept up cruising, in full force, because I had more time. Many days I walked home at dawn with the birds chirping madly overhead. They were comforting. Dawn is a gorgeous time of day. I rationalized how lucky I was to be able to see the sun peaking over the city and smell the air before the exhaust thickened, despite what might have transpired in the hours prior. When I got home, I went to bed, happy to be safe in it. In the morning I’d vow not to waste so much time, do so many men, put myself at ever-increasing risk. In a day or two, I’d do it all over again. The depth to which I clued out was proportionate to the risk—if the risk wasn’t high enough, I was too conscious. For a time it was thrill enough to meet people anonymously. Sex with strangers turned my critical thinker off. When that got to be routine, it was fooling around with someone in a park. Then it was a cluster of men in a park. When parks got too routine, it was peep shows, and too-public bathrooms. Peep show rooms were great because they were a public establishment—technically only one person per booth was permitted, though nobody, not even staff, paid attention to that. The narrow aisles made it easy to watch all the drama (this, too, was better than TV). When the aisles and booths got boring there were glory holes for peeking through. Then using. It took years to get accustomed to any particular environment. The clientele changed enough from one night to the next that the lustre of the illicit remained intact until both the behaviours of a place were recognizable and my own response was predictable. I recognized that this or that behaviour would prompt a particular response in me. When I grew very adept at recognizing the patterns of a place, and its clientele—because I studied the rules—my automaton stopped taking over. It was boring, I guess. In some ways cruising was an elaborate testing lab of human nature. I’d spent my childhood learning how to read people to keep me out of harm’s way, and now I was using all those skills to put me back there, to curate an experience. Although the compulsive mind was at the helm when I was cruising, it could check in with the critical mind for advice without releasing control. It would dip into knowledge when necessary—how to avoid being mugged, how to avoid being arrested, how to avoid being molested by someone undesirable, how to avoid being penetrated without a condom. It was like the compulsive mind had enough wherewithal to not put me in too much harm’s way, just enough to do its work. Too much harm would have threatened my ability to continue the behaviour. Everything about cruising is an exercise in reading and control. If you’re in a public place and want to be groped by only the people you find attractive, where everyone might have their dicks out, that environment requires a great sensitivity to the subtleties of reading other men, as well as keen strategy for how to manipulate a situation. Where to stand, what to touch, when and how to bend over or stand up, what body language to send out or retract. You aren’t just working the people around you, but are also keenly attuned to the guy you’re with. Is he into this third or fourth guy too, and if so, or not, how to accommodate that request? As an adult child of an alcoholic with a classic preoccupation with people-pleasing, cruising meant a master orchestration of making everyone happy. Sometimes I curated the men around me—I could ensure I’d keep the interest of the man I wanted by hitching a competitor to some compulsive cocksucker I’d seen earlier. I’d literally face one guy towards another and let them play out their furtive dramas. Grab a dick and point it at a hole. That usually worked reliably, though much went into making sure I got the right people facing the correct direction, to ensure what I wanted was left available. In my attempt to be more careful, I’d try to set rules for myself—only blowjobs, only men who kissed, only one man at a time, only three men a night, only someone whose features I could see by the light of the moon—but each time I grew more comfortable in a particular scene, the rules dropped away to ramp up the stakes. Nerves were the tool by which I disappeared. Like a button being pressed, nerves locked my anxiety behind a heavy wooden door. One late night, I drove across town to meet up with a twenty-something straight guy at a garage where he worked. The building was classic small business auto repair. The exterior was run down, with an office for the shop on the far left and a half dozen beater cars parked in the lot.

I was told to knock on the door to the workshop itself, next to the two large garage doors. From the exterior, it was impossible to know if anyone was inside. There were no windows on the front of the building to show any light. When I knocked, the door opened on a young ox in a ball cap. He was barrel-chested, about five foot eleven, with arms thicker than my thighs. He had to have weighed well over two hundred pounds. He could have bench pressed me with one arm. He didn’t say anything right away, so I said, “Hey,” and gave a nod. All he did was step back to make way for me. The door didn’t open flush with the floor, it had a foot-high lip, so I had to step over it to get in. When I passed through, he closed the door and I noticed that he locked it with a key that then went in his pocket. That was my second clue. The garage interior was filthy, of course, with a mess of tools and car parts. A Corolla with its hood up was parked on the right of the room. The back wall was lined with hubcaps; the floor had pieces of the bodies of what looked like three different vehicles. On the left of the garage was an exposed second level, full of junk, and underneath that were counters stocked with more tools and car parts, the walls lined with stuff. The only window in the place was along the left-side wall there. It was barred. I asked how he was doing and he nodded, with the smallest of grunts, which I thought might have been, “Good,” but I didn’t hear it properly. He regarded me a second, then looked to the floor, staring straight ahead. I waited for him to say something, but he wasn’t snapping out of it. “Everything okay?” I asked. “Nervous,” he answered. When we’d been chatting online, he’d said he was straight and this was a new thing, so it was no surprise he was uncomfortable. “Do you want to change your mind?” He shook his head no, without taking his eyes from the spot on the floor he was staring at. “I’ll be fine,” he said. “Just relaxing.” We stood like this for some time, a couple minutes, maybe, while I watched him struggling inside himself. He was a handsome enough guy. A round face, blue eyes. His muscles seemed unreal packed into his shirt, like thick pillows wrapped in a sheet. Five minutes must have passed. He barely moved. “I can go if you’re not comfortable,” I said. He shook his head no again, and lifted a few fingers up, gesturing “stay.” “It’s the coke, I did some coke, it…messes my speech.” He spoke like he had three large marbles in his mouth. He was having trouble pronouncing his words. There were pauses in his phrasing, like his tongue went wild for a second and he had to rein it in. “Okay,” I said. “Just nervous.” He looked at me a second. “Never done this before.” “Ever?” I asked. “Just one guy but we…didn’t do much. Jerked him off.” “We don’t need to do anything,” I said gently. “We can just talk.” He sort of nodded again, slowly. There was another long pause, where I looked around the room, trying to be casual. “We can just make out, if you want,” I suggested. When I glanced back at him, his lips were moving. He was talking to himself. I waited another minute, for whatever debate to subside, but it didn’t. The room began to feel wired with electricity, like everything was buzzing. The smell of rubber tires grew more intense. The fluorescent lights were brighter. The oil on the floor more black. “We can just talk,” I said. “We don’t have to do anything.” His head didn’t move but his eyes snapped to me. “I want to. I’m ju-just relaxing. Wired.” He glanced back to the floor for a second, then sprang forwards, walking to the left of the room, to the nook with shelves and tools. Rummaging in the pockets of a jean jacket hung on a nail, he pulled out a pack of cigarettes, removed one, and lit it. He smoked, staring at the floor, mumbling to himself. I felt invisible, like he was ignoring the fact that I was there. And at the same time, too visible, like I shouldn’t be witnessing this guy’s crisis. I shouldn’t be within it. The door was locked. He had the key. Nobody knew where I was, at midnight. When you’re in a situation that is potentially dangerous, it’s easy to try to convince yourself it isn’t. Maybe I’m imagining things. Maybe I’m assuming the worst. I can’t know what’s going on in that guy’s head. He’s just weirded out. He’s probably not crazy. It’s the coke making him talk to himself. That could be normal. You don’t know what coke can do, except that in movies it makes people violent. Maybe movies are lying. Maybe this guy who is so big he doesn’t have a neck isn’t violent. I tried talking to him about what he might like to do, thinking that if I got him out of his head, he’d be fine. Often the fear of a thing is far greater than the doing of it. But his answers to my questions were again brief. Or he just didn’t answer. He barely looked at me, preferring to stare at a spot on the floor ten feet ahead of him. He took a drag on his cigarette and asked me, still looking at the floor, “What’s your dick like?” When I answered, he nodded. He continued mumbling, this time more intensely. His lips were speeding. A sort of visceral, animal fear crept up my limbs. I’ve only experienced that Spidey-sense one time before, in Hawai’i when local friends convinced me to walk on a silver-coloured lava field to see a glowing hole—all of which thoroughly freaked me out—before we travelled around to the other side of the opening and realized we’d been standing on a wide foot-thick shelf over top of a creek of yellow flow. Fear like that is instinct. A cold sweat crept behind my ears. If he was going to freak out, it seemed wise to be prepared. My phone was in the car. There was no back door. I looked around to see if there was anything particularly good to use as a weapon. A saw, a rubber hammer, long bolts, a tire iron on the wall about eight feet away. What did he have near him? Dozens of metal objects he could pick up and use. I looked to the door of the garage, as if I could confirm it was as locked as it seemed. Getting the key from him would be impossible, so where in the garage could I go if he came at me? Was there some way to climb to the second floor and barricade that door? How might I push him off the ledge if he tried to climb after me? What would be the best tool? If I pushed myself under the car, would he be able to pull me out? Would I fit? If I locked myself in the chassis, would he have keys? Would the doors lock? Could I lock them all before he got one open? And then what would I do? Wait him out? Because I’d already mentioned I could just go home and he’d replied that he wanted me to wait him out, I didn’t want to say I was leaving in case that pissed him off. Somehow I had to get him to unlock the door. “I might like some pot,” I said, “to calm me down too. Do you smoke weed?" He nodded. “Yeah.” “I’ve got some in the car. In the glove box. We could smoke that.” “C-can’t smoke in here,” he said. “I can smoke in my car. We can, if you want some. Nobody will see us.” “Don’t want any,” he said. “Okay, but I’d like some. I’m just gonna go get it. I wanna relax too.” “The door’s locked,” he said, turning his head to look at it. “Sure. I’ll be right back. Just need a little toke.” He nodded again, then walked to the door. I watched him pull out his key, insert the teeth, turn the latch, then swing the door open. Streetlight fell onto the oil-stained asphalt in the garage. Calmly and decidedly I walked past him, stepping over the lip. Unlocking the door to my car, I opened it and crawled in, reached across the driver’s seat, as though into the glove box, then came back out. He was standing outside, next to the door, ten feet away. “You know,” I said, “I’m bagged, Buddy. I should go. It’s probably better we try this another time, when you’re less nervous.” “Okay,” he said. His face, which had been pretty expressionless up to this point, seemed to fall. He suddenly looked innocent, a kid who didn’t get ice cream as promised. “I’ll see you around,” I said, trying to sound light and jovial. Not until I was on the highway did I think I was free of him. I looked in my rear-view mirror to see if he was getting into a vehicle, but the door was closed again on the garage, and there was no sign of him. Only when I arrived at my condo did I notice my hands were aching from my grip on the steering wheel. |

My Body is Yours: A Memoir

by Michael V. Smith

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015

Description from Arsenal Pulp Press

In this, Michael V. Smith's first work of nonfiction, he traces his early years as an inadequate male―a fey kid growing up in a small town amid a blue-collar family; a sissy; an insecure teenager desperate to disappear; and an obsessive writer-performer, drawn to compulsions of alcohol, sex, reading, spending, work, and art as a means to cope and heal. Drawing on our preconceived notions about the body, this disarming and intriguing memoir questions what it means to be human. Michael V. Smith asks: How can we know what a man is? How might understanding gender as metaphor be a tool for a deeper understanding of identity? In coming to terms with his past failures at masculinity, Michael offers a new way of thinking about breaking out of gender norms, and breaking free of a hurtful past.

by Michael V. Smith

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015

Description from Arsenal Pulp Press

In this, Michael V. Smith's first work of nonfiction, he traces his early years as an inadequate male―a fey kid growing up in a small town amid a blue-collar family; a sissy; an insecure teenager desperate to disappear; and an obsessive writer-performer, drawn to compulsions of alcohol, sex, reading, spending, work, and art as a means to cope and heal. Drawing on our preconceived notions about the body, this disarming and intriguing memoir questions what it means to be human. Michael V. Smith asks: How can we know what a man is? How might understanding gender as metaphor be a tool for a deeper understanding of identity? In coming to terms with his past failures at masculinity, Michael offers a new way of thinking about breaking out of gender norms, and breaking free of a hurtful past.

MICHAEL V. SMITH is a writer, comedian, filmmaker, performance artist and occasional clown. He teaches creative writing in the interdisciplinary program of the Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies at UBC's Okanagan campus in BC's Interior. Vancouver Magazine has considered him one of its city's 25 most influential gay citizens whereas Loop Magazine named him one of Vancouver’s Most Dangerous People. Website: www.michaelvsmith.com

Author photo: David Ellingsen

Author photo: David Ellingsen