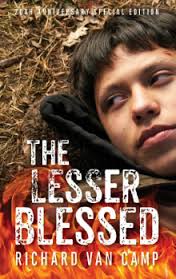

Carleigh Baker Reviews the 20th Anniversary Edition of Richard Van Camp's THE LESSER BLESSED7/18/2016  Richard Van Camp Richard Van Camp The Lesser Blessed: 20th Anniversary Edition Douglas & McIntyre 2016 Yes indeed, it’s been 20 years since The Lesser Blessed, Richard Van Camp’s powerful and compelling debut, found its place in Canadian fiction. In the introduction to the 20th anniversary edition, Van Camp reminisces about the first time he held the book in his hands: “There it was and I couldn’t take it back: I had fired an arrow of flaming light into the world and I had no idea who it would find.” As it turns out, the book would find a wide and receptive audience, including director Anita Doron, who adapted the story into a film in 2012. Straddling the market between YA and adult fiction, and blurring the boundaries of the “Indigenous lit” grouping, this book is hard to categorize, and that’s a good thing. The Lesser Blessed is a high school coming-of-age story set in the remote Canadian north. Though based on Van Camp’s hometown of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, he dodges an issue faced by writers who come from tight-knit communities by creating the fictional town of Fort Simmer. By doing this, Van Camp says his family and friends were able to let their guard down and engage in the narrative. It’s clear that abuse, addiction and depression have marked this community. But, as Van Camp says, this is a story of healing. And that spirit is embodied in the character of Larry Sole. Larry is in many ways a typical teenager. But he is also a second generation residential school survivor, a term for children who didn’t attend the schools themselves, but who suffered greatly due to inter-generational trauma. Many of those who experienced abuse at residential schools went on to become abusers themselves. This is certainly the case with Larry Sole’s father, whose posthumous presence casts a long shadow over the narrative. However, the impact of residential schools is not a major theme in the book—Van Camp chooses instead to focus on the familiar teenage realms: school, house parties, and smoky coffee shops. Kids hang out, make out, listen to music and get into fights. But the sights and sounds curated by Van Camp remind the reader that this is not an urban “Everytown.” Often these reminders are comical— Larry’s mom harping on him first thing in the morning to go shoot them a moose for the winter—but often they’re dark and disturbing. While thinking about a summer from his youth, Larry recalls: “We used to play in the sand way down the beach. We’d take some toys down and build houses. We’d also sniff gas. I wasn’t too crazy about it at first, but after seeing my dad do the bad thing to my aunt, it took the shakes away.” Like most of the characters in The Lesser Blessed, Larry doesn’t fit into the good/evil binary of mainstream literature. He is immediately endearing for his upbeat, sassy attitude and his honesty. So endearing, in fact, that it’s difficult to process the violent fragments of his past that Van Camp slowly reveals. The Larry we think we know is a beacon in a community that even the youngest kids call “a warzone.” The teens spend most of their time trying to escape their reality via typical teen avenues, but Larry has no interest in drinking and drugs. That is, until he befriends Johnny Beck, a swaggering Métis boy who has recently moved to town. Johnny is handsome and tough, and protects Larry from bullies, but he’s also a conduit to parties and girls. One girl in particular holds Larry’s interest—the aptly named Juliet Hope. Larry remains loyal to Johnny despite Johnny’s relationship with Juliet. While this loyalty isn’t necessarily rewarded, a certain transcendence on Larry’s part helps him to meet the pitfalls of friendship with good-natured stoicism. As Van Camp says: “Larry’s story is so dark, so brutal, so raw, so real, but ultimately a story of hope and resilience and how love can save lives.” If that sounds a little cheesy, let me reassure you, this book is anything but. In The Lesser Blessed, Van Camp focuses mostly on male relationships. Larry and Johnny’s friendship dominates the narrative, and provides a great deal of the novel’s humour. Larry’s relationship with Jed, his mom’s boyfriend, is a close second. Having suffered greatly at the hands of Larry’s father, Verna Sole balks at the thought of another serious relationship. But Larry thinks Jed is solid, and wants a positive male presence in his life. Readers receive very little insight into the subtleties of Jed and Verna’s relationship, or into Verna at all. While there is an implied reverence and respect for the adult female characters, they are, for the most part, background. Even Larry’s backstory with the school bully offers more nuanced details than his relationship with his mom. Though she’s the centre of Larry’s teenage universe, the character of Juliet is a damsel in distress archetype, with a dash of angel/whore. On the road to maturity, this is arguably as far as most teenage boys have gone with their perceptions of women. Larry often refers to Juliet as the town slut in between his aching expressions of love, but never with obvious malice. If anything, he’s a gushy romantic: “I had it bad for Juliet. I wanted her for my secret, my prayer. I wanted her as my sweet violence of seeds and metal. I wanted to spill candles with her, to hold hands and walk around in gumboots with her. I wanted to do everything with her.” Larry’s emotions may veer toward the melodramatic—as one would expect from a teenage boy—but Van Camp is steadfast in his avoidance of narrative sentimentality. Despite the poetics, the sum total of Larry and Juliet’s interactions appear to offer little more than a spark in a moonless night. But it’s something. In fact, in the context of Larry’s life, it’s pretty epic—the culmination of his quest to lose his virginity to Juliet. And speaking of poetics, The Lesser Blessed offers a subtle but engaging look at language and dialect. Van Camp himself does not speak Dogrib, and Larry’s use of the language is confined to a few words. Many Indigenous languages have been in decline for years, so a character like Larry might not speak his own language fluently, but he still recognizes its importance. At times this makes him somewhat of a teacher. Through Larry, Johnny learns that “Edanat’e” means “how are you?” and in a funny exchange that follows, Johnny relates this knowledge to his sassy younger brother: “Edanat’e?” I asked. Again, these moments are infrequent, but what we see more often in the text is what Larry calls “Raven Talk.” This local dialect appears to be mostly made up of slurred English. However, its significance shouldn’t be overlooked. Raven Talk is essentially a shared language between all the characters of Fort Simmer, despite their cultural background. Here’s an example: “You bet!” I [Larry] called out. “I’ll do that. Sol later.” “Sol later is Raven Talk. It’s “See you later” said really fast. The correct response is “Sol,” but Johnny didn’t say it. A James Dean-esque loner, Johnny’s initial failure to pick up on this dialect could be seen as indicative of his inability to integrate with the community. Interestingly, Johnny’s younger brother gets the hang of Raven Talk pretty quickly. These brief cultural exchanges are used sparingly, but to great effect, if only in their ability to remind the reader of the cultural divide in the town of Fort Simmer. As Larry says: “I’m Indian and I gotta watch it.” The importance of storytelling is also explored here. Stories are often used as a form of medicine. Though Larry has problems with his memory, particularly in recalling the traumatic events of his past, he is recognized as an excellent storyteller. Van Camp doesn’t confine himself to traditional Dogrib or Dene mythology in The Lesser Blessed. Early in the novel Larry recounts a somewhat hallucinatory tale, originally told to him by Jed. The story, which takes place in India, is about Jed and his friends smoking hash and then being attacked by a gang of neighbourhood monkeys. These evil monkeys become re-occuring characters in Larry’s fevered dreams and drug trips—their symbolic presence often precluding a painful memory. This may be bitter medicine, but it’s necessary for Larry’s well-being. Between the flashbacks, the stories, the myths and the present, reading The Lesser Blessed is a little like watching an episode of Robot Chicken. Instead of formal chapters Van Camp uses titled sections that vary in length from a paragraph to several pages. Overall, the snapshot-style narrative isn’t difficult to follow, but it occasionally slides around with little warning. Sometimes flashbacks occur without a section break, but intense imagery (like the evil monkeys) or change in Larry’s language—which becomes quite cryptic and poetic—lets us know we’re in for some time travelling. Considering the current success of sketch comedy shows, it’s probably safe to assume that readers’ abilities to follow along have increased since the novel was first released. Interestingly, Van Camp claims that, even twenty years later, he wouldn’t change a word of The Lesser Blessed. Has a writer ever made such a claim? Maybe, but it’s uncommon. In Van Camp’s case it feels less like egotism and more like a sign of his reverence for Larry, for the purity of his character’s journey. Dark, graphic, and emotionally intense, this is still a story of healing. Despite the dated music references (Timeless classics, some might argue) The Lesser Blessed is still very current, which is at once a testimony to Van Camp’s writing and a poignant commentary on how little has changed for some Ingenious communities in Canada. Healing takes time, but Larry’s resilience is a trait that will easily inspire readers for another twenty years. CARLEIGH BAKER is a Cree-Métis/ Icelandic writer living on unceded Coast Salish territory. Her work has appeared in subTerrain, PRISM International, Joyland, and Matrix. She won the Lush Triumphant award for short fiction in 2012, and is a two-time Journey Prize nominee. She writes reviews for The Globe and Mail, and is the current editor of Joyland Vancouver. Bad Endings, Baker's debut short story collection, is forthcoming with Anvil Press in spring 2017.

1 Comment

|

Rusty ReviewsMonthly reviews of poetry and fiction. Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed