Shot-Blue Shot-Blue By Jesse Ruddock Coach House Books 2016 Jesse Ruddock’s powerful debut, Shot-Blue, is at once charged with lyrical energy and grounded in a complex, human understanding of trauma, desire and loss. Set in a northern landscape of lakes and forests filled with miners, loggers, vacationers, and the people who eke out a marginal existence at the edges of the tourism and resource extraction industries, the novel follows Tristan, the son of Rachel, a waitress and occasional prostitute, through the loss of his mother and a summer working at a resort on one of the lakes. Shot-Blue is divided into two sections. In the first, Rachel quits her job and retreats to her father’s cabin on an isolated island. Ruddock keeps a narrow focus on Rachel, Tristan, their relationship, and Rachel’s attempts to care for both of them. The section ends when Rachel, having moved closer to civilization for the winter, learns that she has never had title to her father’s island, and that it is being taken over by men who are building a resort; she wanders out into the winter, dying of exposure on the lake ice. In the second, substantially longer section, the novel opens out, including the staff and guests at the now-finished resort where Tristan lives and works. Although the cast of characters is larger, the second section shares the same concerns as the first, revisiting and expanding on the same themes, and using the same incandescent language. And it is Ruddock’s language that is perhaps the most striking feature of the novel. Ruddock has an eye for detail and a gift for metaphor. Take for example this description of the boarding house that Rachel and Tristan leave behind when they move to her father’s cabin: It was painted white a long time ago and now the paint shed in chunks like receipts. The place was famous for this: it was a miracle the siding wasn’t bare. If you lived there, flaking paint was part of your weather. It fell like snow when the wind had fingernails. On still days, it floated down like leaves and melted on the ground, forming pools of warm blue-silver. When tourists casting off the dock at the resort catch fish, they “rise to the surface throwing up wan, shredded, half-digested minnows, little pieces of flesh that [look] like [they’ve] been run through a washing machine.” Ruddock gives even mundane moments resonance and depth. This description of Tristan staring out over the lake in the late evening is rich with echoes of his relationship with his mother and that still raw loss: Tristan walked to his lookout on the far side of the island facing west, where the sunset would be most indelicate. But he was late, the sky had already bled colour like dried flowers. There wouldn’t be more sunset now, only a fading of light. He thought about watching it happen, but he felt such unrest he couldn’t stay. He looked across the mulled water and thought about climbing down and getting into it and going all the way out. But he would never do it. He didn’t want the deep water and didn’t care if it wanted him. He didn’t even want to remember what it felt like. It was her lair now. Ruddock’s adroit and revealing diction, such as the use of “indelicate” and “mulled” here, complements her eye for detail and her use of metaphor. Ruddock’s language is consistently, often unexpectedly, beautiful, but this is not a pretty book. Shot-Blue is set in an environment permeated and defined by violence, its menace, allure and traumatic consequences. Rachel has a facial scar: “It nicked her left temple then ran down her jaw, tent-covering a depression where a full, round cheek should have been.” Its origins are never explained, but it marks her out as a victim, and suggests a past that has left her as emotionally wounded as she is physically scared. The burning of Rachel’s father’s cabin by the men building the resort is a kind of violence, and is perceived as such by Tristan who vows to burn the whole island in revenge. In the second section of the novel, the boys who work at the resort play a game in which they take turns punching each other. Tristan himself invites violence, letting the other boys punch him without attempting to defend himself. Tristan’s desire to be beaten, to be disfigured, is also the desire to connect with his dead mother by becoming, like her, the object of violence, by inviting it to mark, transform and erase him. The novel mixes love and mourning together with self-annihilation in a complex amalgam that testifies to the centrality of violence to the lives of its characters. As part of this violence, bound up with it and happening alongside it, is the transformation of people, particularly women, into objects to be exploited. Rachel remembers prostituting herself as a teenager: Rachel would sell herself to a friend. She didn’t think of it as selling sex. They were not good friends, but he would pay her, and they went like that, having sex in his bedroom, even when his parents were home, for about a year until he got a girlfriend. Another time, it was one of her brother Sheridan’s friends, who’d heard about what she’d done. He asked her, said he liked her, he wouldn’t tell Sheridan, and he would pay. At fifteen, she had no other way to get money. She knew those boys, and she wasn’t afraid of herself. Friendship and sexual exploitation overlap, suggesting that even close relationships are defined by a casual brutality. This pattern is repeated when Rachel realizes she needs money to buy the few extra supplies she and her son need to survive on the island. She starts an affair with Keb, a man who ferries tourist around the lakes in his boat. Like her friendships, the affair has emotional content, but is defined by Keb paying her for sex. In the second section, Stella and Emiel, two guests at the resort, toy with Tomasin, a young girl working there for the summer. Their games are more refined than Rachel’s exploitation, but they still, at their core, involve the reduction of the girl to an object, to a plaything that can be manipulated, possessed and then discarded at the end of the summer. This pattern is not limited to female characters. When Rachel dies, Keb feels responsible for Tristan, and finds him work and a place to stay at the resort. This is at once an act of kindness—Keb has no duty to protect Tristan: he is not the boy’s father and he was only the mother’s john—and an example of this pattern of exploitation: Keb keeps all of Tristan’s pay, cutting his kindness with selfishness, effectively saving the boy by selling him into servitude. Although this pattern is not limited to female characters, it is primarily limited to them, and Tristan is a special case. He is the only male character to love, first, his mother, and, then, when she arrives at the resort, Tomasin, without participating in their exploitation, as human beings rather than objects. Through Tristan, Ruddock registers the collateral effects of trauma, exploring how it spreads out from its focal point along lines of emotional connection, wounding those attached to it along these lines as surely as those who experience it directly. From one perspective, Tristan, with his defensive interiority and his desire for self-annihilation, is the effect of damage done first to his mother and then to Tomasin. This understanding of trauma, its impact, legacy and capacity to transform even those it does not immediately touch, speaks to the novel’s penetrating emotional sensibility. On the back cover, Rivka Galchen praises it as “a genuinely wise novel,” and she is exactly right. This is not to say that the novel does not have its flaws. Although Ruddock’s supercharged writing makes for some of the Shot-Blue’s best moments, it is not always a strength. In the second section, the novel widens its scope, introducing a handful of new characters. Of these, only Emiel, one of the resort’s guests, is given a detailed background, and these characters’ relationships to each other and to the concerns of the novel take some time to develop. When not sufficiently grounded in character and plot, Ruddock’s metaphor-driven and imagery-laden language can sometimes fall flat. And the novel drags somewhat through this middle portion. But the second section does slowly begin to echo and expand on the themes of the first section, and it picks up momentum as it moves towards a closing handful of pages that gather together the threads of the narrative into a spectacularly written and wrenching finale that is well worth the reader’s patience. I began this review by saying that this novel is about trauma, desire and loss. This might suggest that Shot-Blue is a poetic meditation, that it is, like too many novels that are poetic and meditative, easy, even anodyne, but this is book is not that at all. Its beautiful language is bound up with violence. Its poetry is gritty. Its truths are difficult, uneasy. And, although it is not flawless, it will reward you with some genuinely great closing pages. AARON SCHNEIDER is a Senior Literary Editor at The Rusty Toque. His stories have appeared in the danforth review, Filling Station, and The Puritan.

3 Summers 3 Summers By Lisa Robertson Coach House Books, 2016 Contrasting her previous titles, such as Debbie: An Epic or Cinema of the Present, with the newly released 3 Summers, Lisa Robertson—in conversation with Charles Bernstein—suggests that her latest title veers away from the “book as a unit of composition.” Rather than pursuing a particular query for the duration of the book, Robertson implies that 3 Summers is more of a poetic “grab bag.” As a collection of 11 long poems that are each independently gorgeous—and commissioned for diverse, but often fine arts contexts—the idea that these are single poems operating as freestanding agents rings true. At the same time, however, key words, thought processes, creative involvements and concerns repeat, pulse, loop back and insert themselves persistently into the texts, and the collection is further unified by the emotive artwork by Hadley+Maxwell that appears throughout. For me, 3 Summers as a book-length work comes together to articulate a cohesive, poetic feminism: “the total refusal of each existing narrative of femininity” (“The Middle”); it incorporates fleeting rewritings of myths, reappropriations of derogatory terms, and fluid, nonlinear glimpses of form. (It should also be noted that the lines I quote and build my analysis on are culled from a cross section of the book; typically, the lines derive from a reading of 3 Summers as a whole and an enjoyment in linking the common concerns that draw together the distinct poems.) * A major concern throughout 3 Summers is the reversal of the traditional dialectic division between intellect and sensuality. Robertson topples the philosophical entitlement of mental exertion and the scientific prerogative of linearity on its head. She embodies thought and infuses creativity with the rigor of cognition, reversing the established dichotomies, embracing the possibility of a collaboration, an oscillation, between intellect and the senses instead. This book opens with the poetic speaker “lying in the heat wondering about geometry / as the deafening, uninterrupted volume of desire / bellows, roars” (“The Seam”). Immediately, there is not so much a juxtaposition as an inclusion of a highly abstract form of mathematics and the pulse of arousal. “Now it’s time to return to the sex of my thinking” (“The Seam”), Robertson writes, projecting the coexistence of intellectual stimulation with physical pleasure: “I made my muscles into thoughts.” (from “A Coat”) An offshoot of this valorization, or intellectualizing, of sensuality is an ongoing project throughout 3 Summers, which takes the form of an ideology of hormones. Traditionally, hormones go hand in hand with an excess of emotion, the irrational counterpart to logic. The hormonal is often a depreciatory code word to diminish female experience in a vague, offhand way—oh, she has her period, oh, she’s pregnant, oh, she’s menopausal. Robertson channels the uncontainability of hormones or the nondefinitive, fluid context of hormones away from their negative connotations, embracing its ubiquity and allowing it to suffuse her text. The omnipresence of hormones throughout 3 Summers is a fine counterexample to the supposed “grab bag” structure of the book; hormones periodically slip into the poems as a thematic thread running through them. The reader would be hard pressed to escape from hormones as they reside in and progress through the poems, and the promise lingers that “Everything will be a hormone” (“The Seam”): “What I witnessed was But hormones are more intentional than a verbal tic or recurrent allusion. For Robertson, they exceed the boundaries of the letters that spell out the word to become the vessel for poetic expression itself as she celebrates: “The poem is a hormone” (“The Seam”). The reinscription of stereotypically feminine volatility as a form of creative omnipresence is one of the strongest feminist statements I’ve come across in poetry. If hormones serve as a container for poetry, then, at a structural level, poetry points away from rigidity and linearity and towards fluidity, openness, and formlessness as form. “You could say that form is learning,” a process of acquisition (“On Form”). Form is not content, but rather that which forces the content to adjust, that which makes it uncomfortable. If hormones are a factor of disturbance biologically speaking, then in poetry, they can motivate agency and transformation: “is form / a dog as a horse as a deer as a / fish and a bramble a grater rapacious / the second cervical vertebra” (“On Form”). Form is continual transmogrification. Attending a recent public conversation and reading with Johanna Skibsrud hosted by Concordia University’s Writers Read Series, I made a note to myself on my phone, wanting to remember the phrase, “truth procedure, not truth claim.” Although I attributed the words to Alain Badiou, I can’t remember, unfortunately, whether they are a direct quote or Skibsrud’s interpretation of his work. Either way, these words resonate, for me, with Robertson’s writing, for in the process of reversing the hierarchy of intellect and sensuality, she never positions her new mode of thinking as an absolute. While there is a reverent inclusion, or reinvigoration, of hormones, Robertson never crowns hormones as a new ultimate: “there is actually no binary – just the juiciness and joy of form otherwise known as hormones” (“Third Summer”). The instant that one imagines understanding, this semblance of truth melts and a new truth, an ongoing, fluid truth procedure, emerges. * Thematically distinct, but theoretically adjacent to the role of hormones in this book is the preponderance of trees throughout. The Ovidian myth recounts Apollo aggressively pursuing Daphne, a water nymph. As the chase got heated and he was about to overtake her, rape her, she invoked the gods, an act that both saved her and transformed her into a tree. Although this myth is never directly alluded to in 3 Summers, it lingers at the peripheries of my reading experience. Trees, a woman’s relationship to or interaction with trees, the woman as tree, “the / philosophy of the tree” (“Toxins”) combine as another dominant thread that winds through and weaves the poems together:

Trees, in their lush, green vitality, in their gnarled materialization of wisdom, adopt significance, in these poems, as the locus of regeneration and strength. Arboreal aspiration becomes a catalyst for creative expression. Given that in the instant that Daphne shouts out to the gods and voices herself she becomes a tree, it can be argued that utterance as self-activation inspires metamorphosis—metamorphosis into an organism, a tree, that, by definition, never stops growing. Robertson unfurls her speaker. Through a process of verbal photosynthesis, she breathes, speaks and, expressing herself, grows, so that soon her “skin is treebark” (“On Form”) and her words emanate from a sylvan physique: “I had thought In an organic turn of phrase, the poetic speaker has transformed both into a tree—a highly regarded, almost mystical transfiguration—and a dog. In complete contradiction to all cultural programming that condemns calling a woman a dog, a bitch, as one of the lowest possible insults, the dog’s bark resounding gruffly in Robertson’s poem is amplified and enriched to the vibrancy of poetic expression. Barking, here, is the verbalization of tree bark as skin; it is the transformation, the process; it is a primordial mode of expression that doesn’t exit through the throat, but emanates from the entirety of the body’s surface. In this context—reclaiming the figure of the female dog and aligning it with the potency of the tree—it makes complete sense that Robertson strategically positions “the total refusal of each existing narrative of femininity” as “explained to the dog” (“The Middle”). * Robertson autographed my copy of 3 Summers with the words “a tiny draft of coolness” (“The Middle”). Comparing notes after the fact, three or four friends noted that they had received the same inscription. Now that I’ve discovered this line on page 57, I can’t stop wondering whether repeatedly choosing that particular phrase to sign her book was a deliberate authorial nudge, whether the poem on that page includes some kind of specially synthesized message about the book as a whole. Even as I mock my own attempt at manipulating poetry into an exegetic conspiracy theory, I circle the words “in hormonal forest” centred on that same page. Whether Robertson intentionally led me to these words or not (probably not), the obvious confluence of these two concepts—hormones and trees—strengthens my analysis of the collection, at the very least, for myself. * 3 Summers is an incredibly rich text and, of course, I am unable to cover all the material that I had intended to. In particular, I regret not developing on the notion of the feminist goddess; the thematization of the reading process; the triangulation of the collection with the title’s temporality—three summers’ seasonal stasis, recurrence and unrest. Finally, in the spirit of full disclosure and my decidedly subjective stance, Lisa Robertson’s is the book that has moved me most in recent years. Its poetic extremities heighten and sharpen a gentle torsion of nerve endings. It is philosophical, not in the sense of predicating itself on existing theories, but in its honest, necessary articulation and assertion of new, radically contemporary thought. KLARA DU PLESSIS is a poet and critic residing in Montreal. Her chapbook, Wax Lyrical—shortlisted for the bpNichol Chapbook Award—was released from Anstruther Press, 2015, and a full-length collection is forthcoming from Palimpsest Press. Poems have recently appeared in Asymptote, Canthius, CV2, PRISM, Minola Review, among others. She curates the monthly, Montreal-based Resonance Reading Series, and writes reviews and essays for Broken Pencil Magazine, The Montreal Review of Books and The Rusty Toque.

Carleigh Baker Reviews the 20th Anniversary Edition of Richard Van Camp's THE LESSER BLESSED7/18/2016  Richard Van Camp Richard Van Camp The Lesser Blessed: 20th Anniversary Edition Douglas & McIntyre 2016 Yes indeed, it’s been 20 years since The Lesser Blessed, Richard Van Camp’s powerful and compelling debut, found its place in Canadian fiction. In the introduction to the 20th anniversary edition, Van Camp reminisces about the first time he held the book in his hands: “There it was and I couldn’t take it back: I had fired an arrow of flaming light into the world and I had no idea who it would find.” As it turns out, the book would find a wide and receptive audience, including director Anita Doron, who adapted the story into a film in 2012. Straddling the market between YA and adult fiction, and blurring the boundaries of the “Indigenous lit” grouping, this book is hard to categorize, and that’s a good thing. The Lesser Blessed is a high school coming-of-age story set in the remote Canadian north. Though based on Van Camp’s hometown of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, he dodges an issue faced by writers who come from tight-knit communities by creating the fictional town of Fort Simmer. By doing this, Van Camp says his family and friends were able to let their guard down and engage in the narrative. It’s clear that abuse, addiction and depression have marked this community. But, as Van Camp says, this is a story of healing. And that spirit is embodied in the character of Larry Sole. Larry is in many ways a typical teenager. But he is also a second generation residential school survivor, a term for children who didn’t attend the schools themselves, but who suffered greatly due to inter-generational trauma. Many of those who experienced abuse at residential schools went on to become abusers themselves. This is certainly the case with Larry Sole’s father, whose posthumous presence casts a long shadow over the narrative. However, the impact of residential schools is not a major theme in the book—Van Camp chooses instead to focus on the familiar teenage realms: school, house parties, and smoky coffee shops. Kids hang out, make out, listen to music and get into fights. But the sights and sounds curated by Van Camp remind the reader that this is not an urban “Everytown.” Often these reminders are comical— Larry’s mom harping on him first thing in the morning to go shoot them a moose for the winter—but often they’re dark and disturbing. While thinking about a summer from his youth, Larry recalls: “We used to play in the sand way down the beach. We’d take some toys down and build houses. We’d also sniff gas. I wasn’t too crazy about it at first, but after seeing my dad do the bad thing to my aunt, it took the shakes away.” Like most of the characters in The Lesser Blessed, Larry doesn’t fit into the good/evil binary of mainstream literature. He is immediately endearing for his upbeat, sassy attitude and his honesty. So endearing, in fact, that it’s difficult to process the violent fragments of his past that Van Camp slowly reveals. The Larry we think we know is a beacon in a community that even the youngest kids call “a warzone.” The teens spend most of their time trying to escape their reality via typical teen avenues, but Larry has no interest in drinking and drugs. That is, until he befriends Johnny Beck, a swaggering Métis boy who has recently moved to town. Johnny is handsome and tough, and protects Larry from bullies, but he’s also a conduit to parties and girls. One girl in particular holds Larry’s interest—the aptly named Juliet Hope. Larry remains loyal to Johnny despite Johnny’s relationship with Juliet. While this loyalty isn’t necessarily rewarded, a certain transcendence on Larry’s part helps him to meet the pitfalls of friendship with good-natured stoicism. As Van Camp says: “Larry’s story is so dark, so brutal, so raw, so real, but ultimately a story of hope and resilience and how love can save lives.” If that sounds a little cheesy, let me reassure you, this book is anything but. In The Lesser Blessed, Van Camp focuses mostly on male relationships. Larry and Johnny’s friendship dominates the narrative, and provides a great deal of the novel’s humour. Larry’s relationship with Jed, his mom’s boyfriend, is a close second. Having suffered greatly at the hands of Larry’s father, Verna Sole balks at the thought of another serious relationship. But Larry thinks Jed is solid, and wants a positive male presence in his life. Readers receive very little insight into the subtleties of Jed and Verna’s relationship, or into Verna at all. While there is an implied reverence and respect for the adult female characters, they are, for the most part, background. Even Larry’s backstory with the school bully offers more nuanced details than his relationship with his mom. Though she’s the centre of Larry’s teenage universe, the character of Juliet is a damsel in distress archetype, with a dash of angel/whore. On the road to maturity, this is arguably as far as most teenage boys have gone with their perceptions of women. Larry often refers to Juliet as the town slut in between his aching expressions of love, but never with obvious malice. If anything, he’s a gushy romantic: “I had it bad for Juliet. I wanted her for my secret, my prayer. I wanted her as my sweet violence of seeds and metal. I wanted to spill candles with her, to hold hands and walk around in gumboots with her. I wanted to do everything with her.” Larry’s emotions may veer toward the melodramatic—as one would expect from a teenage boy—but Van Camp is steadfast in his avoidance of narrative sentimentality. Despite the poetics, the sum total of Larry and Juliet’s interactions appear to offer little more than a spark in a moonless night. But it’s something. In fact, in the context of Larry’s life, it’s pretty epic—the culmination of his quest to lose his virginity to Juliet. And speaking of poetics, The Lesser Blessed offers a subtle but engaging look at language and dialect. Van Camp himself does not speak Dogrib, and Larry’s use of the language is confined to a few words. Many Indigenous languages have been in decline for years, so a character like Larry might not speak his own language fluently, but he still recognizes its importance. At times this makes him somewhat of a teacher. Through Larry, Johnny learns that “Edanat’e” means “how are you?” and in a funny exchange that follows, Johnny relates this knowledge to his sassy younger brother: “Edanat’e?” I asked. Again, these moments are infrequent, but what we see more often in the text is what Larry calls “Raven Talk.” This local dialect appears to be mostly made up of slurred English. However, its significance shouldn’t be overlooked. Raven Talk is essentially a shared language between all the characters of Fort Simmer, despite their cultural background. Here’s an example: “You bet!” I [Larry] called out. “I’ll do that. Sol later.” “Sol later is Raven Talk. It’s “See you later” said really fast. The correct response is “Sol,” but Johnny didn’t say it. A James Dean-esque loner, Johnny’s initial failure to pick up on this dialect could be seen as indicative of his inability to integrate with the community. Interestingly, Johnny’s younger brother gets the hang of Raven Talk pretty quickly. These brief cultural exchanges are used sparingly, but to great effect, if only in their ability to remind the reader of the cultural divide in the town of Fort Simmer. As Larry says: “I’m Indian and I gotta watch it.” The importance of storytelling is also explored here. Stories are often used as a form of medicine. Though Larry has problems with his memory, particularly in recalling the traumatic events of his past, he is recognized as an excellent storyteller. Van Camp doesn’t confine himself to traditional Dogrib or Dene mythology in The Lesser Blessed. Early in the novel Larry recounts a somewhat hallucinatory tale, originally told to him by Jed. The story, which takes place in India, is about Jed and his friends smoking hash and then being attacked by a gang of neighbourhood monkeys. These evil monkeys become re-occuring characters in Larry’s fevered dreams and drug trips—their symbolic presence often precluding a painful memory. This may be bitter medicine, but it’s necessary for Larry’s well-being. Between the flashbacks, the stories, the myths and the present, reading The Lesser Blessed is a little like watching an episode of Robot Chicken. Instead of formal chapters Van Camp uses titled sections that vary in length from a paragraph to several pages. Overall, the snapshot-style narrative isn’t difficult to follow, but it occasionally slides around with little warning. Sometimes flashbacks occur without a section break, but intense imagery (like the evil monkeys) or change in Larry’s language—which becomes quite cryptic and poetic—lets us know we’re in for some time travelling. Considering the current success of sketch comedy shows, it’s probably safe to assume that readers’ abilities to follow along have increased since the novel was first released. Interestingly, Van Camp claims that, even twenty years later, he wouldn’t change a word of The Lesser Blessed. Has a writer ever made such a claim? Maybe, but it’s uncommon. In Van Camp’s case it feels less like egotism and more like a sign of his reverence for Larry, for the purity of his character’s journey. Dark, graphic, and emotionally intense, this is still a story of healing. Despite the dated music references (Timeless classics, some might argue) The Lesser Blessed is still very current, which is at once a testimony to Van Camp’s writing and a poignant commentary on how little has changed for some Ingenious communities in Canada. Healing takes time, but Larry’s resilience is a trait that will easily inspire readers for another twenty years. CARLEIGH BAKER is a Cree-Métis/ Icelandic writer living on unceded Coast Salish territory. Her work has appeared in subTerrain, PRISM International, Joyland, and Matrix. She won the Lush Triumphant award for short fiction in 2012, and is a two-time Journey Prize nominee. She writes reviews for The Globe and Mail, and is the current editor of Joyland Vancouver. Bad Endings, Baker's debut short story collection, is forthcoming with Anvil Press in spring 2017.

The Wake The Wake By Paul Kingsnorth Unbound 2015 The Wake is a thoroughly English book. The English writer and thinker Paul Kingsnorth has written Real England, a book about the impact of globalization on the cultural identity of the English. The Wake is his first novel, and it is set in England during the 11th century Norman invasion, a turning point in English history. Yet this book has something to say about modern Canada and our struggle to reconcile our colonial past and present. Likely, it has something to say about any nation that has colonized or been colonized, but Canada, as a nation that was colonized by the English and the French, should pay particular attention to a story about the English being colonized by the French. It is controversial to suggest we need yet another account of colonization from the English point of view, but The Wake is an important novel in much the same way as Joseph Boyden’s The Orenda. The Orenda is one of Canadian literature’s first balanced accounts of first contact between Indigenous peoples and Europeans, including French and Indigenous points of view, and importantly, multiple Indigenous points of view (it is quite common that Indigenous peoples and their perspectives are presented as a monolith, despite the plural “peoples.”) The Orenda won the 2014 Canada Reads competition, and has been recommended as required reading for all Canadians. The Wake should also be required reading for Canadians, not for its balanced perspective, and only partially for the old “those who don’t know, doomed to repeat” reasons, but mostly because learning that the Norman invasion was itself a colonization and that English people are no more a monolith than Indigenous peoples are and that the way we label people “Anglo-Saxon” is almost as misguided as the way we used to label Indigenous peoples “Indians” is very much in the spirit of reconciliation. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s mandate states that “The truth of our common experiences will help set our spirits free and pave the way to reconciliation.” The Wake addresses the themes of common experience, colonization, violence, and even cultural genocide. If that doesn’t grab you, The Wake is also a hell of a story, told by the unforgettably unreliable Buccmaster of Holland, in his own words, and in his own language, a “shadow tongue” which the author invented to immerse the reader in Buccmaster’s “angland.” The main things a reader should know about this “shadow tongue” are that Kingsnorth manipulated Old English to be (mostly) intelligible to modern readers, that The Wake contains few words or letters that aren’t rooted in Old English, that it takes about thirty pages to get the hang of it, and that, yes, there is a glossary. The breakdown of Anglo-Saxon England is mirrored in Buccmaster’s spectacular personal breakdown, and, while the shadow tongue roots the story in the past, a Canadian reader can’t help but notice the contemporary relevance of Buccmaster’s tale. But who in Canada even knows about this period in history? Cultural references are few and far between, and most of what we do know is simply the date, 1066. Thinking across a thousand years of history can be overwhelming. Here in Canada, we’re just starting to wrap our heads around 500 or so years of colonization. In The Wake, we see the Normans (i.e. the French) invade England, effectively ending the Anglo-Saxon way of life, one thousand years ago. But why stop there? Go back another 500 years or so and those Anglo-Saxons are migrating to England and becoming Christians. Five hundred years before that, the Romans occupied England. Each of these events are marked by violence, loss, and oppression. Reconciliation in Canada is often centred on Indian Residential Schools. Residential schools are specific, unambiguous, and within living memory, which allows them to remind people that reconciliation is a vital thing. But it’s important to recognize how far back the history of colonization goes, too. The Wake shows us that the history is staggering, and still relevant. During some of his rants about the “fuccan frenc,” (which means just what it sounds like,) Buccmaster sounds remarkably like the online comments section of any modern news article about immigration. And like those commenters who won’t budge about “their land” and “their way of life,” Buccmaster is both swaggeringly confident and paralyzingly insecure. Buccmaster has spent much of his life building up a facade of control and power. Raised by an angry, erratic father, he finds respite in a special bond with his grandfather. Grandfather follows the “eald ways” (old ways,) meaning he doesn’t recognize Christ, but, rather, follows the ways and rituals brought by the Anglo-Saxons when they first arrived in England, hundreds of years earlier. Grandfather teachers Buccmaster of Woden (Odin,) Thunor (Thor,) and Erce, who is mentioned just once, but shows how, to Buccmaster, the old ways and the land (the fenn) go hand in hand: and ofer all these gods he saes ofer efen great woden was their mothor who is mothor of all who is called erce. erce was this ground itself was angland was the hafoc and the wyrmfleoge and the fenn and the wid sea and the fells of the north and efen the ys lands. Grandfather is at least 200 years behind the times. Almost everyone in Anglo-Saxon England was Christian by 1066, including Buccmaster’s father, who is not happy about Grandfather’s insistence on teaching little Buccmaster the old ways. Things come to a head when grandfather dies, and Buccmaster fulfils his promise to give grandfather a traditional funeral, which enrages his father. Buccmaster has been stuck between the old ways and the new his whole life, and those old ways are about to be struck a fatal blow, in what amounts to a cultural genocide for Anglo-Saxons. When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report came out in 2015, many Canadians heard the words “cultural genocide” for the first time, or at least, for the first time as applied to Canada. From the report: States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next. Though England didn’t have an English-speaking ruler for hundreds of years after the events in The Wake, obviously, the English language wasn’t lost. It was drastically changed—the shadow tongue shows the reader how much. It was never endangered, though, as many Indigenous languages in Canada are. But The Wake does portray a form of cultural genocide. Buccmaster’s land is seized. He loses his family, his position, and his possessions. He witnesses his grandfather being stripped of his spiritual practices. He sees the disruption of cultural values in his own family. No wonder Buccmaster is not surprised that he, and he alone, sees mysterious omens of trouble to come, including Halley’s Comet, which really was visible in 1066. Grandfather taught Buccmaster that “angland” has been slowly slipping away for years. Buccmaster refers to England as having its “sawol eatan” (soul eaten) by “ingenga god and cyng” (foreign god and king): my father raised me in the circe of the crist as all did in those times for all was blind lic the frenc is now macan us blind. anglisc folcs has had their sawol eatan i saes eatan first by ingenga god and then by ingenga cyng and now what is angland but an ealong in the mist seen when the heafon mofs but nefer reacced again. Grandfather also gave Buccmaster “Weland’s sword” to remember him, and the old way by. Weland is a legendary blacksmith who is said to have made Beowulf’s sword, among others. After Buccmaster sees omens in the sky, he starts to actually commune with the spirit of Weland. This signals the beginning of Buccmaster’s personal breakdown, but Weland also acts as Buccmaster’s conscience, and as a kind of Greek chorus. In Weland’s first appearance, he introduces himself to Buccmaster as a forger of weapons and a killer of kings: i is forger of wyrd and waepen Weland is alternately encouraging and dismissive of Buccmaster’s ability to resist the invaders, and as moody as Buccmaster himself. As Buccmaster starts to amass a small following of resisters, his insecurities, and Weland’s increasingly erratic instructions, lead to several eruptions of violence. Post-invasion, Buccmaster leads his ragtag group of resisters, or “greenmen” through the woods, where they plot against the French and dream about meeting up with legendary freedom fighter (and actual historical figure) Hereward the Wake, so they can really take a stand. Well, actually, Buccmaster dreads this meeting, because it means he would no longer be in charge. They never find their way to Hereward, and ultimately fail because they are fractured, and because Buccmaster can’t give up control. Anglo-Saxon England as a whole fails in the novel because the people have become disconnected from the land. Because they can’t reconcile the old gods with the new. Because they can’t remember that they came from somewhere else too, that the “frenc ingengas” (French foreigners) are as foreign as they were five or six hundred years earlier, when the Angle and Saxon tribes migrated to England in the first place. That Buccmaster and his greenmen sound remarkably like the “renegade tribes” that resisted colonization in North America 600 years later, and like parents and children who defied Canadian residential school laws during the twentieth century, is both reason to despair and reason to hope. Despair because resistance to colonization has historically been futile; reason to hope because surely, one of these times, we’re going to learn something. Speaking of learning: if only The Wake were Canadian, it would certainly end up on Canada Reads, breaking barriers and changing Canada and all that. If Canadians read this book, and learn about colonization in England, it might go a long way to bringing people around to the concept of reconciliation. But wouldn’t the Canada Reads panelists argue that The Wake isn’t accessible enough? Its language is too challenging. No one will read it. The shadow tongue could make the text impenetrable, or feel gimmicky. It’s a fine line to tread. Kingsnorth believes the shadow tongue was necessary because people in the eleventh century wouldn’t talk like we do now, and that even taking away obvious anachronisms, you can’t just word-for-word translate old into modern English. In “A Note on Language” at the end of the novel, he says, “The early English did not see the world as we do, and their language reflects this… Our assumptions, our politics, our worldview, our attitudes - all are implicit in our words, and what we do with them.” Contrast this with many other historical fiction writers, Canadian and otherwise, who use plain (or plainer) modern language to tell old stories. Australian historical fiction writer Geraldine Brooks spoke on just this subject at Book Expo America last year, and her perspective was in sharp contrast with Kingsnorth’s. In her view, people haven’t changed that much over the years in terms of the way we think, or our motivations; the things that have changed are just “window-dressing.” It’s impossible to deny the effect of the shadow tongue in The Wake, though. Reading about a lost culture in a lost language is chilling. The Wake is more that its experimentation with language, though. It’s a character driven novel, and we are fully in Buccmaster's head. He has to carry the story and a thousand years of history. He is somehow both utterly convincing and deeply unreliable, both compelling and unlikeable, and both prophetic and completely lacking in self-awareness. His delusions of grandeur, persecution complex, jealousy, and defensiveness tempt the reader to diagnose him with any number of psychological problems, none of which would make a bit of sense to him. All Buccmaster knows is that “sumthin is cuman.” Actually, Buccmaster knows more than he’s letting on, and his demons are more frightening than the Normans that burn down his house, killing his wife and servants, early on in the story. Buccmaster knows all about destruction and betrayal, and he learned it before any Norman walked on his land. Buccmaster shows us violence and degradation on a grand and a personal scale. At one point, as those around Buccmaster finally begin to realize what’s happening (they’re not going to resist the invaders), someone laments that “a bastard will be our cyng and angland will weep for a thousand years.” We’re closing in on a thousand years now, several hundred of which England spent colonizing the rest of the world. When will the weeping stop? In her review, Carolyn of Rosemary and Reading Glasses asks, “How far back does this chain of suffering extend? What does it mean to be English, French, any one people?” These sound much like the questions Canadians ask about reconciliation: how far back does this pain extend? How many generations have suffered, will suffer? What does it mean to be Canadian? Kingsnorth doesn’t have the answers, but he shows us how people have grappled with these questions for millennia, including the English, colonizers of the modern era. Kingsnorth has created a historical fiction experience that goes so far beyond “immersive” that it’s essentially its own genre. Whether you have British ancestry or not, if you live in Canada, The Wake is part of your history. And no matter who you are, it is essential reading. LAURA FREY is a book blogger at reading-in-bed.com. She lives in Edmonton with her husband and two children. She is on Twitter at @LauraTFrey.

Double Teenage Double Teenage By Joni Murphy BookThug March 2016 Dear Sarah, I am sitting in a café in Vancouver trying to write a review of Joni Murphy’s Double Teenage. Kayla and I are procrastinating by dreaming up a literary reading series and courting the affection of the establishment’s resident cat. Other writers keep coming by the communal wood table we’re seated at and adding to our discussion. I can’t help but feel like everything I’ve read or experienced up until this point is potent and enmeshed. And today it makes a good web, and I can see a way forward, but I know there are days when this intertwining of experience, history, and theory conspires darkly, when I feel conscripted to perpetuate and witness oppressions, and when I am confused about how to survive it. I am concerned about how art raises questions I cannot answer. These are the issues Murphy addresses in her novel about two curious women whose trajectories remind me of our own. I keep meeting folks who know you, who speak highly of your dedicated friendship and activism, who tell me how you are this beacon of queer, radical light in your community. I’m not surprised that they adore you like I do. I only wish that our lives overlapped in real time rather than twinning obscurely through graduate school and the queerness we’ve pursued from different sides of the country. I’m proud of how we survived growing up in the same, awful small town, how we endured its material and psychic violences. And, while we share this history, what is more amazing is how what we’ve built for ourselves as adults yokes us together even now. How art, survival, and violence interact on local and global stages is the tension that underpins Murphy’s novel. Allegorical yet timely, Double Teenage tells a dark and beautiful tale of two childhood best friends, Julie and Celine, who grow up together in the Southwest in the 1990s. They drift apart while studying art and theory as adults in their adopted homes of Vancouver and Chicago. But their lives remain intertwined because of their shared desert incubation and the struggles they face when they enter the academy and the art world. Murphy captures how women navigate both subject and object positions—how they flicker between experiencing the world and observing themselves in it. And this is what brings Celine and Julie together in addition to their childhood friendship and philosophical pursuits. Murphy writes: “They learned so much; they learned to think about themselves as if from the outside.” Murphy tracks how this subject-object position plays out broadly in the culture, and in the minutiae of the everyday and the interpersonal, demonstrating how Julie and Celine subsume and attempt to resist the limitations imposed on them through their art, writing and relationships. The novel charts the intricacies of a formative friendship as it converges and diverges over time. Julie and Celine first bond over their mutual love of local theatre where they learn about performance on stage and in real life. As teenagers, they witness the intimate links that bind people together, in productive and violent ways, in the microcosm of a desert college town. As adults, they follow different but similar paths into the broader world where they grapple with the saturation of routine and systemic gender-based violence. From their privileged positions within grad school, Murphy shows the progressive philosophical bubble to be fraught with contradiction and its own patterns of oppression. In response to this challenge, the women arm themselves with language—Julie writes critical essays about the portrayal of dead girls’ bodies; Celine creates performance art that processes a hometown tragedy; and they both write tender, complex love letters to partners and sometimes to each other. Murphy suggests that art can magically rally and heal and just as easily obscure and harm. Julie’s experience in graduate school gets at this complex relationship between language and experience: Julie kept encountering the figure of the cutter; philosophers seemed to love these crazy girls. Though she read about it and recalled vividly Celine with blood running down her arms and Band-Aids under her dresses she would not speak up in class. Julie hated the women in the women’s studies classes who described their own experiences in relation to the text but she remained silent about that as well. She hated the girl in her program writing a thesis on sex positivity. She made her face a mask. Julie actually preferred reading European men who clearly had female troubles. Murphy chooses a difficult, conflicted stance for the novel as it thinks through the North American obsession with violated and dead feminine bodies. There is no clear way forward because critical thought can connect people, but also alienate them from each other. The text integrates the Ciudad Juarez femicides and Robert Pickton’s murders of women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside into its plot, mirroring white middle-class engagement with gendered, racialized, class-based violence. Murphy shows how we learn about these kinds of atrocities from the media often in a shabby but safe kitchen and then mull them over in unresolved discussions at parties. Importantly, Murphy chooses to not deploy the murders as ominous, distant hauntings: they are integrated with urgency into both the plot and form of the novel. For example, while in the Pacific Northwest, Julie writes about Laura Palmer’s specter in Twin Peaks and notices “philosophers [who] seemed to love these crazy girls.” In the middle of this academic task, she reflects on an example of gender-based violence from her hometown. Murphy then juxtaposes Julie’s academic life in Vancouver with the emerging details of the Pickton murders—his family’s social and economic rise and his targeting of vulnerable women on the margins of society. Later, in a more formally innovative section of the novel, the author reprimands Canadian indifference by quoting former Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s comments that the rampant murder of First Nations women is not a sociological phenomenon. The overlapping layers are dizzying, but necessary. The text bears witness and refuses to forget. In the final portion of the novel, Murphy experiments with form, weaving Celine and Julie’s narratives together with media and theory. In the concluding numbered sections of the novel, the text relinquish its adherence to verisimilitude and becomes pithier as well as more poetic, incantatory, associative, and combative: The girls were getting to that point where they felt almost able to grasp what was happening but it made no difference. They still felt crazy. Knowing would not be enough and pinning something down was impossible. The violence they first thought of as geographically specific was actually miasmic. Its specific hue was bound up with their place and time. But even still, the hues of these violences were in the same family, red fading to black, black fading to brown. 90. No one is to blame Or blame goes round and round […] This is a play about the bloody spotting of system, the ruined panties of the state. The progression from realistic, beautiful narration to a looser collection of sprawling meditations is effective—Murphy commits to telling the story in plain terms and then scrambles the narrative to ask larger questions. She earns our trust before opening the novel up to its glorious and challenging irresolution, inviting readers to investigate their own relationships to the representation and processing of oppression through art. Murphy’s novel is a fairytale set in real places that have their own mythologies and histories—the surreal desert, the rainy Pacific Northwest, the chilly and gritty Northeast. In her depictions of these settings, Murphy demonstrates how reality and metaphor superimpose to form a place: Celine felt the desert was a science fiction. This kind of landscape doesn’t appear in the real world or TV except as the setting for alien planets and westerns. The novel takes the lives of young women seriously. Murphy shows how danger is often nearby, known, mundane. Double Teenage doesn’t quite feel like a coming-of-age novel, although that is a fine genre. It’s more properly in line with Chris Kraus’s theory-as-novel genre. In its exigent dialogue with popular culture, high art, and theory that connects to women’s experiences and desires, Double Teenage is reminiscent of I Love Dick. However, in Murphy’s novel, the distant love between two women proffers the site of projection onto which the two characters hurl their thoughts and feelings. And Murphy seems to suggest this interpersonal connection that endures despite external and internalized misogyny is magic and is its own dizzying and overlapping network of survival and creation. In a culture mostly interested in the spectacle of dead girls, Double Teenage is a formally provocative counter spell to the facts of violence. Anyway, Sarah, I couldn’t help but knit you into this narrative. I know you’d have your own interpretation of the novel, nuanced and different from mine. I think we could have a discussion about race that makes explicit some things Murphy touches on implicitly. I don’t think the novel is direct and urgent because I relate to Julie and Celine. While the trajectory of my life resonates with theirs, I still felt a cool distance from the characters—maybe that’s the queerness or my age. But there are channels of ferocity and tenderness in the novel that I laud. You know about the ongoing labour of fierceness and empathy. When I hit the final lines of Murphy’s novel, in which Julie lovingly addresses her estranged friend Celine, I immediately thought of you: I miss you with my whole heart. And so Murphy’s novel is compelling me to write to you in the hopes that my message will create a wormhole, that it will fold the continent so that I can reach out to you in Montreal and share this affirmative spell. ADÈLE BARCLAY'S writing has appeared in The Literary Review of Canada, The Pinch, PRISM, The Fiddlehead, and elsewhere. Her debut collection of poetry, If I Were In A Cage I'd Reach Out For You, was shortlisted for the 2015 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in fall 2016. She is the Interviews Editor for The Rusty Toque.

Legacy Legacy By Waubgeshig Rice Theytus Books August 2014 Recently I was railing to my patient partner against some writer whose short stories were too consistent from sentence to sentence, by which I meant that there was no variety of style. Consistency of quality is, however, an obvious virtue. Still, who gives a shit if a few of the sentences in Waubgeshig Rice’s Legacy are clumsy and distracting? For one thing, there are other sentences that are beautiful and powerful. Also, some of the dialogue is written with language and cadence so perfect that it sounds in your head like the characters are speaking there, like the words they are saying never really needed the page anyway, it’s just that the page was the only way to get them to you. But the real reason we, Rice’s readers or potential readers, should not give a shit about the inconsistent quality of Rice’s sentences is the importance of Rice’s story. There are two sentences I think of when I think about story. One is Joan Didion’s assertion that, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” The other sentence is Thomas King’s “The truth about stories is that that’s all we are.” If “the truth about stories is that that’s all we are,” then we are limited by the stories that we have heard about other people and each person is and all peoples are limited by the stories that are told about them. What is the story that I, a white settler who has spent his whole life on the Traditional Territories of the Mississaugas of the New Credit, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat, grew up hearing about Indigenous people? What is the story that I, a settler whose mother’s family arrived in the Greater Toronto Area circa 1815, grew up hearing about First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples? Trouble with drinking. Poverty. Victims of racism and structural racism. The cultures were dead, or nearly dead. Almost all of them. I’d read The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, a play about an Indigenous woman written by the son of Ukranian immigrants. I’d read some Thomas King books other than The Truth About Stories. I’d read Joseph Boyden and I’d taught, pretty ineffectively, Thompson Highway’s plays Dry Lips Oughta Move To Kapuskasing and The Rez Sisters. When students asked me about Native experience in Canada, I had to acknowledge my titanic ignorance. King’s 2012 book The Inconvenient Indian was a gift in this department. So were all the other books that I mentioned above (with the possible exception of The Ecstasy of Rita Joe), but I didn’t have the foundational knowledge to allow me to really take much from them other than a feeling of empathy for the peoples who shared this land with me. Around April or May of 2014, I was asked to teach a Native Studies credit, a grade 9 class called “Expressing Aboriginal Cultures.” I had a lot to learn before September. At the first professional development session I attended, I got a complex lesson. Elder Dr. Duke Redbird was explaining to me the relationship between the Seven Grandfather Teachings and the fruit forest and I didn’t get what he was saying, but I thought I did so I was interjecting eagerly. Patiently, he pushed past my misunderstanding. Eventually, I was quiet enough to listen properly and to understand that I had, at first, misunderstood and that therefore my earlier interjections had totally missed the mark. I started wishing to apologize, but I couldn’t find the courage. That exchange taught me to tread carefully, and reminded me that I knew nearly nothing. I started listening and learning. I am still listening and learning and I have a long long long way to go. A lifetimes worth, at least—centuries worth—that I would like to learn. Look, I know I’m supposed to be talking about Legacy. One thing I have learned, though, is the importance of situating yourself, of self-identifying, and giving other people the chance to do this. I need you, Waubeshig Rice, and you, Dear Reader, to know that I am a babe in the woods here. I’ve been told, Mr. Rice, that my ancestors were taught by your ancestors to live on this continent, to live in the Great Lakes Region specifically--miigwetch to your ancestors. Funny that here I am now learning from you, or at least your book. So maybe babe in the woods is a useful cliché looked at from that perspective. As long as you understand, Reader, that by woods I do not mean to imply an untended, wild or unknown woods, just a woods unfamiliar to me, now, and at one time unfamiliar to my ancestors. Legacy is about the Gibson siblings, Eva, Stanley, Maria, Norman and Edgar. The book starts with Eva in Toronto in 1989. The narrative reveals that three years earlier her parents were killed in a car accident, hit by a drunk driver. Eva is studying at the University of Toronto, an act that requires considerable resilience. She is homesick for Birchbark, a fictional reserve off the highway between Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie, but she also faces harsh prejudice and a feeling of alienation: “Eva was a foreigner on these streets. Although people like her ancestors had navigated the rivers, streams and hills around what came to be known as Lake Ontario for thousands of years, she always felt uncomfortable and out of place in the city.” Eva has resolved, however, “to only return home for good once she got her Law degree.” We go with Eva to an Introduction to Canadian Politics class and the instructor seems like a parody of both a bad instructor and a racist Canadian, so extreme are his perspectives. Because Eva is “one of the few brown faces in the class and the only Native student, as far as she knew,” the professor sees her as “a resource he could exploit to verify everything in the books from which he drew all his course material.” The day’s lesson, looking at “some of the fringe groups that benefited from” the Charter of Rights and freedoms—“immigrants, Natives, and other people not necessarily at the forefront of building this country”—is obviously problematic, at least in its framing. The professor is upset about Section 25, which he quotes: The guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any Aboriginal treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada including any rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 17, 1763; and any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired. Rather than using Section 25 as an opportunity to acknowledge the fact that all Canadians are “Treaty People”—an idea that I don’t remember enjoying much vogue in the late ’eighties—the day’s lesson is an attack, an obvious act of violence. The instructor badgers Eva about the “advantages” she has had, including not having to pay taxes and receiving financial support to attend university. He asks if it isn’t just time for her people—by which he means all First Nations, Metis and Inuit people—to “get over it.” This instructor is one of the many teachers a reader will meet on their way through Legacy, but he is the only one that bothers me. I am torn between feeling like he is too extreme to be possible, that he is too much your racist uncle to be an instructor at a University, and the feeling that his racism seems too likely and too accurate. This instructor commits the first act of violence against Eva, and it is awful. The second act of violence Eva faces is at the end of the first chapter when a man Eva meets in a bar murders her. So, the remaining Gibson siblings are left to deal in their different ways with two tragedies: the loss of their parents and the loss of Eva. Eva’s younger brother, Stanley, resolves to follow in Eva’s footsteps and succeed where Eva was not allowed to. Eva’s younger sister, Maria, has issues with substance abuse, but begins to learn traditional knowledge from an aunt, which helps her change directions. Norman has drinking problems and is unemployed, but his life is saved by his eldest brother Edgar, who not only pulls Norman from the lake Norman is trying to drown in, but starts Norman’s recovery by sharing his knowledge of traditional Anishinaabe practices. Edgar, father, husband and patriarch of the Gibson family after the loss of his parents, is the furthest along the road to reclaiming the traditions that were threatened by Residential Schools and other mechanisms of the Canadian colonial project. Edgar is a youth worker in Birchbark and at a detention centre in Sudbury. Rice’s story of the Gibson family’s resilience and healing is a much more complex story than are statistics or the dominant narratives that were available to me as I grew up. “The truth about stories is that that’s all we are.” Legacy is one of an ever-increasing number of stories that reminds settlers of the consequences of colonialism for the first peoples and first cultures of this continent that many of us love. It demands our empathy and is, therefore, part of the project of reconciling the colonizers of this continent and our hosts. What about, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” though? Every culture I know is built on stories. The Judeo-Christian tradition has a book or two from which people draw stories vital to the lives of various cultures. The Anishinaabe people in Legacy share Anishinaabe stories and Anishinaabe knowledge between generations, and they do it despite attempts by colonizers to replace their stories and knowledge with Judeo-Christian stories and knowledge. It is not surprising to say that if you can prevent a culture’s stories and knowledge from being shared, that is if you kill the stories and knowledge, you kill the culture. There are many stories, the stories in Legacy are among them, that suggest that if you kill a culture, you may also kill some of the people of that culture. In Norman’s case, Anishinaabe teachings are life saving. In a less direct way, they are probably life saving for Maria, too. In Edgar’s case, the ceremonies he learns help him to live in a good way in the face of so much grief and tragedy, never mind the deep frustration of seeing Eva’s murderer let off with a sentence that seems criminally lenient. Stanley is the only surviving sibling who, by the beginning of the book’s final chapter, seems without substantial connection to Anishnaabe ceremonies or other traditional practices. He does have a Master’s Degree, though, and is on contract with the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa. Each character’s life and choices, anyone’s life and choices, are tied up with the stories they are telling to and about themselves. Hold on. I want to talk about the ending, so I suppose that this is your spoiler alert. I’ll try to talk about it so that I make my point but I don’t take from you the potential pleasure of reading the end yourself. Deal? Each of the first five chapters follows a Gibson sibling for a day or two, and each of their stories is augmented by flashbacks. The chapters are, in order: “Eva: Winter 1989”; “Stanley: Summer 1991”; “Maria: Spring 1993”; “Norman: Fall 1995”; and “Edgar: Summer 1997.” The sixth and final chapter of the book is titled “Mark: Winter 1998.” Mark is the man who murdered Eva in the first chapter. What is done to Mark in the final chapter and who does it is, I would argue, intimately connected to which narratives each of the Gibson siblings has chosen as the dominant narrative in their life. The ending of Legacy, as is so often the case, hints at what the author believes about the narratives we “tell ourselves in order to live.” I’m in the middle of reading Indian Killer by Sherman Alexie and there is this line in that book that is relevant to what I’m talking about. A settler character in Indian Killer, Aaron, is trying to find a lost brother, a brother who he suspects is dead. The narrator says of this searching settler, “He needed some kind of ceremony in which to express his grief, but he was without ceremony. Without the ability to mourn properly, Aaron could only steep in his anger.” LEE SHEPPARD publishes fiction weekly on his blog, Not Know, Notice. He is a teacher at West End Alternative Secondary School in Toronto where he has developed and currently teaches two project-based courses: ReelLit a film-studies and video production program and The West Enders, a creative writing and illustrating program that produces an eponymous illustrated literary journal. He was a contributing editor of the literary magazine Pilot and he writes book reviews for The Rusty Toque.

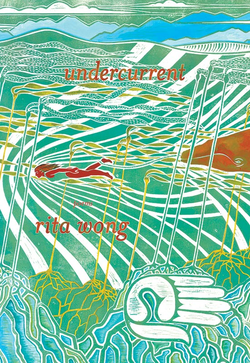

undercurrent, by Rita Wong undercurrent, by Rita Wong Nightwood Editions April, 2015 “let our societies be revived as watersheds” writes Rita Wong in the poem “Declaration of Intent” in undercurrent, her third book-length work of poetry. “not tar but tears,” the poem continues, “e inserts a listening, witnessing, quickening eye.” The poem—and the book— advocates for an affective and immersive engagement with the water systems that support life, a view through water towards a response to the uneven colonial control of resources by state and industry, and the uneven damages to individuals and communities. The poems in this collection propose a poetics and politics of water that acknowledges the ubiquity of water issues—from when we flush to the waste waters of industry. The personal is universal in one’s contact with water, and Wong’s poetry puts itself at the service of water and those who fight to maintain its sovereignty and safety. While reading undercurrent for the first time, I moved from Vancouver back to Ontario, where I stayed in my childhood home in Bright’s Grove on the shores of Lake Huron, and finally moved into St. Catharines on Lake Ontario. My partner and I left B.C. during a period of prolonged drought, in which wildfires filled the city with smoke, and, at the time of writing, continue to threaten inland communities. The need for water has ushered in municipal water restrictions, and raised awareness of and resistance to the province’s dealings with Nestlé over prices and rights to groundwater for bottling. Near Bright’s Grove, Ontario the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, who have seen the so-called Chemical Valley’s petrochemical industry totally surround their community, continues its fight against state and corporate environmental racism for proper air and water testing. I list these personal proximities and interactions with the politics of water because this is what Wong’s book prompts: an attention to the ways in which water rights, sovereignty and purity affect ourselves and those around us. It also highlights a complicity with the methods by which water is controlled and employed unequally under capitalist and colonial power: “calm in chronic pollution, kindred water is a secret player reflecting industrial flaws back to us” (“bisphenol ache”). Through an attention to environment in these poems the calm of consumption becomes unsettled in its reflection in water and water poetics. The poem “immersed” lists many pollutants, life forms, and experiences brought together through water systems: immersed in chlorinated water The poem moves between ubiquitous contaminants and the life-support of water in a meditative mode that lulls with repetition, but unsettles in its reflective criticism. immersed in carbon dioxide As “carbon dioxide” finds a connective consonance in “the colonial present” and is then disrupted by the calm of “loonsong,” which in turn is affected by “endocrine disrupting dust” the list ebbs and flows in waves of critical attention. Water may be polluted and made hazardous through capitalist management, but it also presents a subversive undercurrent that, as the book’s epigraph by Bruce Lee suggests, is “formless, shapeless,” but can “flow, or it can crash.” So too does poetry in this collection. It flows between forms, allowing the language to shape an embedded critique. undercurrent’s most noticeable formal trait is the intermittent printed waves that occupy the bottom of the page throughout the collection in which quotes appear. These quotes play a role similar to epigraphs (which the book also employs occasionally), but extend beyond the poem to give the sense that this poetry arises from a dialogue with other authors, other words. Below “declaration of intent,” the words of Wes Nahanee, from the Squamish Nation, flow: “water is unstoppable.” Rather than using the words as epigraphs to directly situate the concerns or contexts of the poem, these aquatic footnotes give the sense of an engaged poetics that seeks dialogue and response. This technique is similar in some ways to Wong’s use of marginalia in her previous collection, forage, in which handwritten quotes border many of the poems. Both techniques foreground the dialogic activity of poetry, and the poems become conversations with others that subvert the logics of an “I”-based lyric. undercurrent’s poetic forms include recurring sections of prose spoken by a “we”: Who are we? We are beings who need clean water in order to live a life of dignity, joy and good relation. Maybe you are part of “us” without even knowing you are. Maybe we are the ones who are too often taken for granted or ignored, the quiet witnesses to atrocities, greed, mean-spirited hierarchies, hostages of capitalism. The immersive pronouns flow in a repetitive, though always critical, attempt to sum up the impossible complexities of water’s reach. “We” are complicit, “we” are victims, and Wong’s poetics here makes room for the seemingly contradictory relations that water enacts. Such fluidity, though, does not preclude a crashing response in these poems: “Dripping & and spitting, we rise.” And later: “we are undercurrent.” Such sections sometimes arise, in Wong’s collection, from documentary prose paragraphs (also marked by italics), in which the poet’s experiences as an environmental activist and ally are described. As with the undercurrent of quotation, these sections highlight the poems’ political focus and service to a cause. This resists a decadent logic that would see poems function as isolated experience, and instead instigates a poetics that, like water, flows beyond its boundaries, always towards the rivers, lakes, and oceans that support life. One such documentary section describes the Healing Walk for the Tar Sands, in which the poet walked with the first nations communities affected by Alberta’s tar sand and other activists, giving witness to “the brutality that has been normalized through massive industry.” At times, the poetry becomes an almost overwhelming immersion in the language of contamination: broken earth torn hole caterpillar Here, the poem “motherboard” presents a language and water contaminated, refusing all but a few semantic connections. Meaning instead bioaccumulates in the poem. The aural resonances of the chemical “-ine”s and “-ene”s slow reading, which allows the surrounding familiar words to take weight. Wong highlights the histories and biases carried in the familiar as we are “immersed in English” (“immersed”), and highlights that as much as the industrial contaminants sound unfamiliar, so too is English a colonial linguistic contaminant that erases the languages of the land’s first peoples. Wong returns these poems of water to aboriginal languages. The poem “immersed” ends with the line, “immersed in q’élesxw.” “Q’élesxw” is a verb meaning “to return” and “give back” in the Halq’eméylem language of the Stó:lō group of first nations peoples who inhabit B.C.’s Fraser Valley (www.firstvoices.ca). Further on in undercurrent, a poem entitled “q’élesxw” appears, in which “the city paved over with cement english cracks open Halq’eméylem springs up” The poem replaces the familiar language and artifices of the city and its dominant language with the traditional, ancestral words of the Fraser Valley. In this the poems gesture towards a hopeful return to the immersed, and, for many, forgotten, language of the stó:lō – in English: “water.” Through a poetics of “q’élesxw” and water, the poetry of Wong’s collection resists indulging in despair, and instead it offers cracks in capitalism, industry, English and the language of colonialism in which alternative narratives and social relations may be written and imagined. The collection concludes with “epilogue: letter sent back in time from 2115.” The prose poem offers a future history in which “spontaneous compassion sprouts in the cracks of collapsing systems,” and “people…watch water’s journey the way they used to watch the dow jones.” The poem describes a speculative fiction that offers an alternative to capitalist pollution and linguistic contaminants, and propels the poetics of water beyond despair and inaction. In this way, undercurrent offers poetry that is engaged in critical hope for the power in the watersheds of language and political resistance. ANDREW MCEWAN the author of repeater, a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award, and the chapbooks Input / Output, This Book is Depressing, and, Conditional. His work has recently appeared in Canadian Literature, Lemon Hound, Poetry is Dead, The Puritan, and Avant-Canada: More Useful Knowledge. His next book, If pressed, is forthcoming from BookThug. |

Rusty ReviewsMonthly reviews of poetry and fiction. Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed