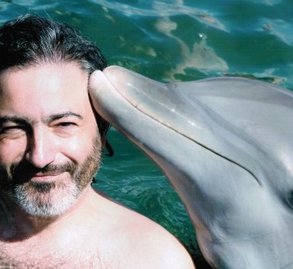

RUSTY TALK WITH GARY BARWIN GARY BARWIN is a writer, composer, multimedia artist, and the author of 18 books of poetry and fiction as well as books for kids. His most recent collection is Moon Baboon Canoe (poetry, Mansfield Press, 2014.) Forthcoming books include Yiddish for Pirates (novel, Random House Canada, 2016), I, Dr Greenblatt, Orthdontist, 251-1457 (fiction, Anvil 2015) and Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry of Paul Dutton (WLUP, 2015). Other recent books include Franzlations (with Hugh Thomas; New Star), The Obvious Flap (with Gregory Betts; BookThug) and The Porcupinity of the Stars (Coach House.) He was Young Voices eWriter-in-Residence at the Toronto Public Library in Fall of 2013 and he is Writer-in-Residence at Western University in 2014-2015. Barwin received a PhD (music composition) from SUNY at Buffalo. Barwin is winner of the 2013 City of Hamilton Arts Award (Writing), the Hamilton Poetry Book of the Year 2011, and co-winner of 2011 Harbourfront Poetry NOW competition, the 2010 bpNichol chapbook award, the KM Hunter Artist Award, and the President’s Prize for Poetry (York University). His young adult fiction has been shortlisted for both the Canadian Library Association YA Book of the Year and the Arthur Ellis Award. He has received major grants from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council for his work. Recordings of his work can be found at PennSound.org and on his YouTube channel. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario and at garybarwin.com. Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Gary Barwin: I was a single cell. There was a flurry of macromolecules—DNA, RNA, a wad of proteins—and then I wrote another cell into being and I became two cells. I kept writing until I was millions. This was my mother tongue before I had a tongue. There was no editing, until my father cut my nails. Unless, my first creative writing memory was when I was 6 and writing on little cue cards, making up a writing system that seemed to hold the largeness, the numinosity of what could be said. I wrote a bunch of strange little sentences that were spells or poems in this made-up script that didn’t “mean” anything. And I do remember writing “Cosmic Herbert and the Pencil Forest” a short story in Grade 5 and publishing it to sell at the school “White Elephant” sale. My first publication. KM: You are probably one of the most diverse writers in this country. You are a poet, a fiction writer, a children’s author, a performer, an artist, and a musician—is there an art form that you have not tried but want or plan to? And how do you decide what genre or form a project will take? GB: There are so many things I’d like to try. I can’t help wanting to try my hand at a variety of things. I feel that there are so many exciting and inspiring ways to imagine writing, how could I just settle on one? I see a continuum of approaches to creative work. On one extreme, there are writers like Samuel Beckett who worked his entire long career on narrowing the focus of his writing until he arrived at the laser-like minimalism of his later work. And then there are the writers who explore many different modes of creation, all part of one big messy creative ecosystem. bpNichol was one of these. The composer/writer/visual artist/performer John Cage was another. As for me, I am currently working on a multimedia piece that will involve sound poetry, spoken text, computer processing, live music, recorded music, video, visual poetry and dancing giraffes. Ok, I’m lying about the giraffes. They won’t be dancing. Unless, of course, they want to. The whole shebang is inspired by the work of iconic Canadian writer of “borderblur,” bpNichol and uses archival recordings of his performances. So I guess the answer is, I’d like to explore ways to further combine my various interests. I’m also also really interested in exploring film. I’ve made a few short videos by myself and in collaboration and I’ve found it very inspiring. And I’d like to work with various kinds of computer processing of text—I mean beyond spell check. There are so many fascinating things that can be done with even simple programming tools to create interesting texts or interactive text-experiences. I’ve done a few, but I’d like to explore this more. I find these kinds of projects really amazing and attractive. I’m also planning an art exhibition of my visual poetry work, which is something I’ve wanted to do since crayons. In terms of how I decide what genre or form a project takes, it is like cell division. I start with one tiny bit of something and then try to follow what it wants to develop into, trying to be open to what it might be. Or sometimes, I consider a form or a genre and think, “Hmm. I wonder what I could do with that? What possibilities does it offer? How would it make me create something that would surprise me or take me away from myself and my usual way of doing things?” KM: You’ve been very involved in the small press and chapbook scene as a writer and publisher. Can you tell us a little bit about how you got involved and how that community impacted your writing and publishing life? GB: It’s probably terribly gauche to do this, but I’m going to shamelessly plagiarize an answer to this question that I gave in an interview with the writer/scholar Alex Porco a few years ago in OpenBookToronto.com. I could, like a student once told me he did with stolen essays, run it through Google translator, first changing into Chinese, then Urdu, then back to English so that it becomes an “entirely new essay,”—actually I do do that with some poems to see what interesting changes occur—but here’s my original answer in the original language, rejigged just a little bit: I’ve been involved in the small press since 1985. In a creative writing class at York University, our professor, the brilliantly laconic and insightful Frank Davey [who then went on to teach at Western], told us about this event downtown called "Meet the Presses", a gathering of small presses devised by Stuart Ross and Nicholas Power. He encouraged us to create books and get a table. I did, and ended up attending both Meet the Presses and independent book fairs for the next thirty years publishing a series of broadsheets, chapbooks, and various ephemera for each event. Stuart, Nick, plus some others of us, re-formed Meet the Presses several years ago in order to create the Indie Literary Market. These kind of community-based writer/publisher events, along with readings and the online world have been a constant and important part of my writing and cultural life. They’ve really contributed significantly to my development as a writer and have been responsible for introducing me to many writers, publishers, friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and readers, and much writing which has been important to me. All of which made my last thirty years of engagement in the literary scene inspiring, collegial, pleasant, welcoming, intellectually engaging, and fun. I see small press publishing and related events like the [Toronto] Meet the Presses Indie Literary Market as responding to, and facilitating community around literature and publishing. The technology of the book is not one merely of information technology, but interactive technology. Readers, writers, and publishers come together to share their joie de livre in a context that is outside the strictures of predominantly market-driven publishing. In the small press, we can turn on a dime because we don’t need thousands of dollars to continue. Our share-holders are people who share in our work by holding our publications in their hands, and share our mutual appreciation of independent literature and publishing. Publishing is not a neutral act. It is implicitly political and aesthetic. The publishing is part of the aesthetic of the work, in terms of its look, its distribution, and how the audience interacts with the work, both in terms of reading it, engaging with its writers and publishers, and in how it finds its audience. In the small press, there is a reason, a conscious decision, to publish the works in the way that they do. The presses choose to publish in this form not because they have to, but because they want to. In this kind of publishing, success is defined as an authentic interaction between engaged writing, publishers, and readers. It’s good to be reminded that we can choose to shape how our writing is and not only be driven by market-, media-, or other social forces. And we don’t have to wait for these outside forces in order to begin to publish and create audience and to make the writing and the community that we wish to see. KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use? GB: bpNichol (who I’ve now mentioned several times) told us in writing class, “to keep writing.” I think that’s wise. Implicit in this, though, is to keep being curious and exploratory in one’s writing. Not to keep writing the same thing or the same way, but to keep trying to get better, to keep actively considering what makes writing exciting and interesting, what works and what is possible. And one can’t write without being an active and engaged reader, and, for most of us, unless we’re Emily Dickinson, an active participant in a literary community. I also remember asking Lillian Necakov, the first one of my friends to have a book published, how she did it. She said, “You write one page and then you write another until you have a hundred pages. Then you have a book.” Also good advice! KM: Collaboration seems to be a big part of your writing and creative life. You’ve collaborated with Craig Conley, Hugh Thomas, Gregory Betts, Derek Beaulieu, Stuart Ross and others. What draws you to collaborative writing? I’m sure it depends on the project, but how do you approach it? GB: I first make it clear that I’m the better, more experienced part of the collaboration and that everyone should take their cues from me. And bring me coffee. Also, I’ve got this itch just an inch below my right shoulder blade and … But, really, the excitement and fun of collaboration is being open to doing something different, to this strange hybrid, hydra-headed process that is collaboration. It is both and neither of the participants’ work. It is very freeing. It is my work, but it isn’t, so I feel even more empowered to try things, to go with the process, to go outside my own sense of self, or my sense of my identity as a writer or even, my sense of what works as a writer. I try to trust the process that happens between me and my collaborators. And the great secret of writing is that you can always change things—tweak, modify, revise. Sometimes collaborations involve some planning ahead by discussing what the project will be; sometimes, it involves just jumping in and seeing what results. Sometimes, it is like playing tennis. One person serves up something that the other has to return. This can be a line, a paragraph or something else. Then the other person answers it. The answer may involve reframing the entire question, surprising, challenging, or confounding the collaborator. Sometimes we proceed line by line, stanza by stanza, or paragraph by paragraph. Sometimes each of us goes back and changes what has been written before. One thing I love about collaboration is that the act of collaboration (the ‘rules of engagement’) are created collaboratively and can change at any time. KM: In addition to being one of the most diverse writers in Canada, you are also one of the most prolific. In 2014 you published the poetry collection moon baboon canoe with Mansfield Press, you have collection of short fiction, I, Dr. Greenblatt, Orthodontist, 251-1447 coming out in 2015 with Anvil Press, and you have a novel Yiddish for Pirates forthcoming in 2016 with Random House. How are you able to write so much? Can you give us a sense of your process and how you move between so many different projects? GB: I was going to write a self-help book “Making Procrastination Work for You!” wherein I describe how one can harness the power of avoiding working on one project by working on another, but I didn’t get around to writing it ... I do find that I get energy from jumping from one kind of writing to another. Prose reminds me what poetry can do and vice versa. Sometimes, though, I do need to burrow deeply into something to give it time to develop—this was certainly was the case with the novel—but then after a long writing session, or sometimes intermittently in the middle of one, I’d write something else as a palate cleanser, on a lark as a diversion, or as a kind of footnote to the main project. I think I write a lot because writing serves many purposes for me. It is a way of figuring things out, a way of working through things, a way of knowing, of experiencing things, of exploring. It is an entertainment, an obsession, a mode of social engagement, of doodling, of spiritual practice, of trying to become a “better” (more thoughtful? more compassionate? more observant?) person, a way of creating, experiencing, and responding the energy and possibility around me and in language. In terms of process, I don’t know that I have a single mode of creation. Often it is the slow accumulation of work, chipping away at ideas or larger forms. I don’t know where I’m going. I have a place where I start writing, but I always consider that the writing knows more than me so I trust the process of writing itself and where it is taking me rather than my ideas for the project. I try to listen to where it is going. I means lots of revision and recalculating. For example, I had some ideas about the novel and where it might go. I even had charts! But they were flexible. I’d head to where seemed the most promising direction. Then when I got there, I looked around to see where next: which was the most interesting direction from this new perspective. And so I kept moving forward. You know that nursery rhyme, “The Bear Went Over the Mountain to See What He Could See?” That’s how I imagined it. I’d walk to the mountain to see what I could see. And then when I got there, I’d look to see if I could see the next mountain from where I’d be able to see what I could see. Until 115,000 words later, I felt I was done. KM: For readers who are first introducing themselves to your work, moon baboon canoe might be a good place to start because it’s a great example of the scope of your writing. The poems in this collection are humorous, nonsensical, profound, personal, absurd, political, and experimental. It’s a goodie bag of poems where each one offers a new surprise. How did this collection come together? Was it written over a long or short time span? GB: Thanks for your kind words. Though I do like books organized around a central idea or theme, I also like books that are, as the pirates say, a salmagundi, a mish-mash. In moon baboon canoe, I hope that the various kinds of poems offer an energetic and/or supportive contrast. I had lots of different kinds of poems kicking around, but Stuart Ross, the editor, and I discussed what kind of a book this might be and so I gathered the appropriate poems together. I shaped the book into sections so that it wasn’t just a big blob of stuff, but rather several smaller more shapely blobs. (That’s like choosing what clothes to wear…) It is a bit like creating set-lists for a band. You shape each set so that it has variety, coherence, and a certain shape or direction. And then you smash all the instruments and jump into the audience. And destroy your hotel room. Oh sorry. That was only when I was in that string quartet. Most of the poems in moon baboon canoe were written in the few years preceding the book and then intensely revised, both before I submitted the book and after consulting with Stuart. Knowing that it would be Stuart who would be looking at the book gave me ideas about revision. I could internalize some of what I thought he might say which enabled me to see the poems with fresh eyes. And then, of course, when he did actually did see it, he did have some comments and suggestions that I hadn’t thought of. I actually love the process of working with a good editor. It is a productive dialogue and a chance to not only fix problems, but to learn of opportunities to make the writing do more. I didn’t always take Stuart’s exact suggestions, but I did listened carefully when he pointed out weaknesses or flabby bits which I could rework, revise, and generally improve. As I said, most of the poems were written in the last few years, however, there are a couple that come from a long time before that. One of them I wrote as an 18-year-old undergrad. I was quite chuffed at the retroactive validation, that, at least, as far as that poem went, I wasn’t as entirely clueless as I thought I was back then. KM: One of the things I enjoy most about your poetry is your sense of humour. In the poem “inside” which starts with the lines “inside Stephen Harper / there’s a little dog” you marry humour and politics into a thematically satisfying and entertaining poem. Poetry often has a reputation as a serious art form. When I talk to writers and readers new to poetry, they are surprised when poetry is funny. Can you discuss your thoughts on humour and poetry? Who are some of your influences? GB: I don’t know why poetry and humour should be thought of as antithetical. Or why humour and “profundity” or depth should be thought of like oil and waiter, Angelina Jolie and Don Cherry, or iPhones and the duodenum. I think of humour as one of the great resources of communication. To surprise, confound, reconfigure, challenge assumptions, to enable lateral thinking, and more complex perspectives. Many traditions recognize this. For example, the spiritual masters who wrote Zen koans, Sufi parables, or Three Stooges shtick. And English: what a delightful narrative of confounding syntactic jokes, slippery orthographic pratfalls, and historic and lexical legerdemain. two roads diverged in a yellow wood I took one it doesn't matter which I'm not giving it back Thinking specifically about humour in poetry, my influences from contemporary poetry include David W. McFadden, James Tate, Stuart Ross, Ron Padgett, Lisa Jarnot, Mark Strand, Steve McCaffery, and I’m going to have to mention bpNichol again (and here, I’m thinking of his sly visual work.) I think I’d also have to include John Cage and Wallace Stevens, More recent influences would include Anne Carson, Gabriel Gudding, Mary Ruefle (do you know her amazing lectures, Madness, Rack, and Honey?) Heather Christle, and Dorothea Lasky. KM: You’re the 2014-15 Writer-in-Residence at Western University. You’ve been very present on campus with various initiatives such as Flashbang—a speed-editing event and Reclaiming the Corridor of Excellence: A Public Performance in which you will be exhibiting curated works in the new Arts and Humanities building. What have you got planned for your second term? GB: I plan to sleep in my office under a pelt made from actual Irving Layton. Unless it’s Naugahyde. And then, I’m doing a few readings including at the London Open Mic, another Flashbang event at the Weldon library which will involve text performance and music, and a multi-media event in conjunction with Josh Lambier’s Poetry Lab. I’ll also do another Flashbang speed-editing event (like last time, with student-writer-in-residence Steven Slowka), and some kind of live performance as part of the Corridor of Excellence project, though I haven’t figured out exactly what yet. As part of the London Public library part of the residency, I’ll also be doing a speed-editing event there, and workshops for seniors, for street-involved youth, and at the London Writers Group. This is in addition to visiting various classes and holding individual consultations during non-Layton-coated office hours. KM: What is your favourite or funniest literary moment, if you have one? GB: When one of my sons was about three (N.B. Ryan: don’t worry I won’t say which son), I took him with me to a reading that I was giving. As I went up to the podium and opened my mouth to read, he ran up, grabbed all of my papers and threw them across the room. Then he exclaimed, “No. I am the writer!” After I gathered my papers, I began to read again. Then he squatted in the corner and shouted, “I HAVE TO POO!” I actually thought the whole thing was quite funny. Why? Was it my Dadaist-Fluxus-anarchist son destabilizing the conventions of the bourgeois reading via a Freudian intervention, or just whacky madness that reminded me not to take things so seriously? Either way, the mostly university-age non-parents were pretty shocked, though the parents thought, “Oh yes, just another Thursday night.” I didn’t bring my son along to another reading until he was much older. Now he’s a musician in Toronto, but I haven’t staged a similar intervention during one of his performances … yet … my son and I have performed together quite a lot in a variety of situations, both literary and musical. And then there was that time that I was driving across the border to read in Buffalo and the border guard, on hearing that I was a poet, read me her (really awful) poetry for ten minutes as the cars lined up for miles behind me. Thanks very much for the questions. I really appreciate it. For our London, Ontario readers who would like to make an appointment with Gary Barwin at Western (between now and April 2015) contact Vivian Fogloton in the Department of English and Writing Studies. GARY BARWIN'S MOST RECENT POETRY BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed