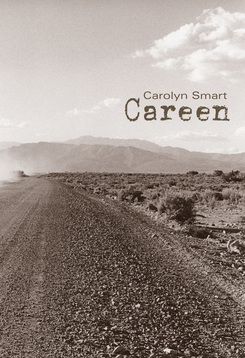

RUSTY TALK WITH CAROLYN SMART Carolyn Smart. Photo credit: Bernard Clark Carolyn Smart. Photo credit: Bernard Clark Carolyn Smart's collections of poetry have been Swimmers in Oblivion (York Publishing, 1981), Power Sources (Fiddlehead Poetry Books, 1982), Stoning the Moon (Oberon Press, 1986), The Way to Come Home (Brick Books, 1993), Hooked - Seven Poems (Brick Books, 2009) and Careen (Brick Books, 2015). Her memoir At the End of the Day was published by Penumbra Press in 2001, and an excerpt won first prize in the 1993 CBC Literary Contest. She has taught poetry at the Banff Centre and participated online for Writers in Electronic Residence. She is the founder of the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers, poetry editor for the MacLennan Series of McGill-Queen’s press, and since 1989 has been Professor of Creative Writing at Queen's University. Hooked has become a performance piece, featured at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2013 and at Theatre Passe Muraille, Toronto, in 2015. I wanted to write about people on the margins of society, and it is important to me that I saw them clearly, with respect and a lack of judgment [...] to widen the gaze, and let the characters breathe. Adèle Barclay: When I first met you, you introduced yourself as a confessional poet. The two collections you’ve published since then, Hooked (2009) and Careen (2015), however, are historical poetic accounts in monologue form. The voices certainly make use of the emotional intimacy and nuance of confessional poetry. What is the relationship between the confessional poetry and these poetic retellings of history? Can these historical voices invite us to revisit the confessional mode with more sensitivity to its masks, personae, and poses? Carolyn Smart: After writing my memoir At the End of the Day (Penumbra Press, 2001) I was tired of telling my own story and longed to lose myself in something new. When Myra Hindley died in November of 2002 I found myself staring at the very different photographs that appeared in two obituaries and wondering who this woman really was. At that same time, I had been invited to read my poetry in a performance poetry series and leaped into writing a new poem specifically for performance purposes, something very different from what I had written before in tone and content. I immersed myself in the life and history of Myra Hindley, and tried to imagine life through very different eyes. And yet, to make her story (and the stories in the six poems that eventually followed and became Hooked: Seven Poems) feel authentic, I accessed my own emotional life, my memories, my experience, and translated them to the page as I had done with all my previous work. If a poem doesn’t feel emotionally honest to me, I know it’s not working. In the end, I found that Hooked was more revealing of my own emotional truth than anything I had written before. For that reason I find it hard to watch the stage versions of the poems, as I feel so exposed. It is very much a collection about vulnerability, about choices and danger and addiction and love, and I wanted to write about these things in the context of women who fascinated me, and could maintain my full attention for as long as it was necessary to translate them to the page. I demand a lot for full engagement; I have a short attention span and am somewhat fickle. I searched and discarded and found what I needed, and I am still in love with some of the seven women to this day. AB: Careen tells the story of Bonnie and Clyde. What drew you to this dusty, bloody pocket of history? Why did you choose to tell this story? CS: To reveal previously untold truths has been an obsession in my writing for nearly two decades, and the story of the Barrow Gang is simply a continuation of this. Many people of my age watched the 1967 film of Bonnie and Clyde and believed it factual, but reading the first person accounts of the gang (Blanche Barrow and W.D. Jones both told their stories) or the recent biography Go Down Together (Simon & Schuster, 2009) by Jeff Gwynn, it’s clear that the film was far off the mark. To know that both Clyde and Bonnie were physically handicapped and mainly lived in their car was a game-changer for me. And more personally, my maternal grandfather Harry Van Tress was a failed gunrunner who lived out his last years in penury in Laredo, Texas, and I have long wondered about him, about the Texas of the depression and the dustbowl, about hunger and the desire to break free from poverty by any means at hand. I wanted to write about people on the margins of society, and it is important to me that I saw them clearly, with respect and a lack of judgment. This is something I was adamant about in the writing of Hooked—to widen the gaze, and let the characters breathe. AB: Careen carries many characters with distinct voices as they tell the beginning, action, and aftermath of the story of Bonnie and Clyde and their gang. How did you manage the vast cast of voices? How did you keep track of them as discrete entities and yet know when to bring them together to create a coherent atmosphere? CS: When thinking about the Barrow Gang I realized there was so much to tell about the time and place they were living in that it had to be revealed by multiple voices. As in any group, the characters were markedly different and I tried to reveal their realities and backgrounds through their own tales. It was easy to differentiate them as many of their individual stories are fascinating. They had to be resilient and resourceful to survive all they did: the fear and the restlessness, the hard scrabble of daily life. AB: Archival newspaper articles and Bonnie Parker’s poetry both anchor Careen amidst the cacophonic stream of voices. The newspaper clippings let the dramatic monologues breathe, almost like a Greek-chorus, and Parker’s poetry lends the collection a mythical, almost prophetic valence. I’m curious about the process of culling from the archives. How did you know what to include? What were hoping to achieve by integrating the historical material into the collection? Also, what do you think of Parker’s poetry? What struck you about it? CS: I used the newspaper reports for two reasons: to clarify the narrative, and to give some sense of how the general public followed their exploits. Bonnie and Clyde were made famous and then torn down by the press; their fame was very bright and short-lived; the nuances of realism were lost in the dust. The fact that Bonnie never killed anyone, that they fell on their knees every single night to pray, that they starved and lived in terror, that the last six months of Bonnie’s life Clyde often carried her in his arms as she could no longer walk, that they loved their mothers dearly, that they travelled with a saxophone, a Remington typewriter, a rabbit, and a dog—these facts don’t jive with how we imagine them: wearing fancy clothes while leaning on a stolen car, cigar in mouth, pointing a long gun, sneering at death. I loved the fact that Bonnie wanted to be a famous poet. The brief time she was locked in jail alone, held on a robbery charge, she wrote a long poem and smuggled it out to Clyde. She craved more from life than she was faced with—as Clyde puts it in one of the poems—‘…in a hole like Cement City when yer yearnin for more & nothin ever happens’ – and she made it happen when she met Clyde Barrow. They broke out. As they careened wildly around the country she sat in the back of the car cleaning and loading the guns, typing poems. Her poems are packed with energy and humour, tight rhymes, clever. You can almost hear her mind tick as you read them. AB: In my first creative writing class with you, you read “Written on the Flesh,” a dramatic monologue from the point of view of Myra Hindley, from Hooked. It was brilliant and chilling. The subject of infamy underpins both Hooked and Careen. Why is this subject so interesting to you poetically? CS: Infamy is an endlessly fascinating topic for me—for anyone—to excavate. Levels of enquiry into character and motive have allowed me greater self-exploration, which has been both surprising and personally rewarding. The astonishment of the writing process amazes me. AB: Hooked was adapted as play, performed by Nicky Guadagni and directed by Layne Coleman. How did that come about? What it like having your poetry transposed into another medium? CS: When I was deep into the writing of Hooked I could see its potential for a dramatic rendering, and had only one actor in mind for the production. Nicky Guadagni and I have been friends for more than 30 years and I recognize her as one of the finest character actors in Canada. I knew she could move into these women and claim them like no one else. Layne Coleman felt the same way—the three of us worked the adaptation out over a period of several years, in different productions and in many different venues. It is both thrilling and terrifying for me to watch it—my imagination come to life before my eyes—and Nicky is simply superb. AB: You’ve been publishing and teaching creative writing for a while now. How has CanLit changed over the years from your perspective? What are you most excited about in the poetry world these days? CS: I’ve been publishing for more than 35 years and things have changed radically—so many very fine poets, well-curated reading series, slams, hiphop, performances, many small and excellent presses. I am disappointed in the paucity of reviewing and the lack of ink on poetry, but I am thrilled by the quality and breadth of material out there these days, and by the stream of very fine students who have passed through my classrooms at Queen’s over the decades. I am constantly delighted, year by year, by the eagerness and drive, the originality and creative risk-taking that I see and encourage year by year. AB: What other writing projects are you working on and dreaming of? CS: After a decade of writing about other people I have come back to my own life for material. This one really surprised me: I began writing about the year 1963, a pivotal year in my life. I lived in three different locations that year: Ottawa, the Gatineau Hills, and then a boarding school on the coast of Sussex, in the UK. At the very end of the year, just before returning to my parents in Ottawa, I was told that the woman who had raised me from birth and whom I loved dearly had died very suddenly. Because my mother was a Christian Scientist, death was never discussed and it was as if it had never happened. This secreted grief suddenly resurfaced for me 50 years later, and I began to write about it. AB: What is your earliest memory of writing creatively? CS: 1963 is a strangely mixed time: not the 60s as we think of them and yet no longer the stiff 50s. We all teetered on the edge of change. I wanted to write about all that. It was also the year when I realized I wanted to be a writer, began writing short stories and biography to ward off loneliness in boarding school. And once, the writer Nicholas Monserrat came to my parents’ house in Ottawa for a party. He looked so confident and smooth; a lovely woman was his companion; he drove to the party in his Rolls Royce. I thought: this is the life. CAROLYN SMART'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed