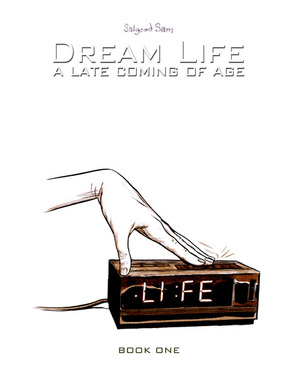

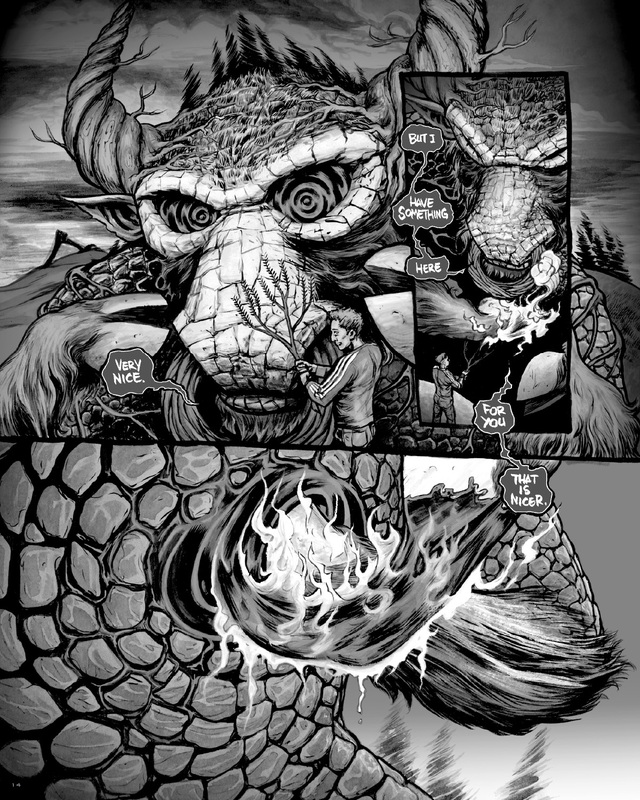

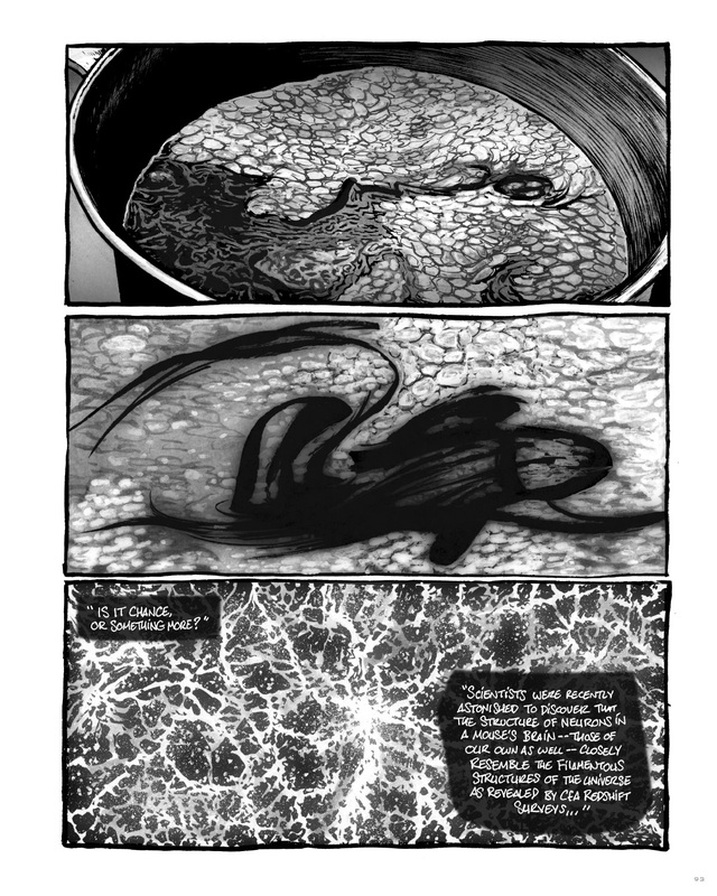

RUSTY TALK WITH SALGOOD SAM Salgood Sam Salgood SamPhoto by Niall Eccles SALGOOD SAM is Max Douglas, born 1970. Since approximately 1996 he’s worked under the nom de plume derived from a reverse spelling of his name. His recent books include the graphic novels Dream Life: A Late Coming of Age, Therefore, Repent! with Jim Monroe, Wonder Woman versus The Red Menace!, a holiday Ghostbusters special “Tainted Love” with Dara Naraghi, a story with Mark Sable in the Eisner-winning Comic Book Tattoo, another of his own in Popgun 4, and work in both Awesome 2: Awesomer and Sea of Red. He lives and works in Montreal with three cats and his partner. He teaches art and blogs about comics. Trevor Abes: What’s your earliest memory as an artist and storyteller? Salgood Sam: For me there isn’t a conscious time before art, because my mother did it. She did illustration, commercial design and a little cartooning, and today she does storyboards for animation. My stepfather and two of my great uncles were also cartoonists. The idea of being a comics artist happened in high school. I walked into my home room, and a friend of mine, George Todorovski, was inking a comic on a light table. That was the moment when I said, “Yeah, I can do that.” I didn’t consider myself a storyteller yet, because I was dyslexic and I avoided the manual exercise of writing, but it’s part of my personality to have my own stories. I was in my mid-twenties when I came into my own as a writer and realized I wasn’t happy just drawing a picture. TA: You got your start in comics in the 1980s by publishing zines and you’ve crowdfunded to great success. What advice do you have for budding artists with stories they want to tell on their own terms? SS: If you want it bad enough and you’re willing to do the work, go for it. Don’t expect anything to be handed to you. Grants are less stressful than crowdfunding, because you fill out the application, send it and forget it. You don’t have to worry about delivering a finished product to customers. The flipside is crowdfunding is better for a storyteller to build a readership. If you’re getting started, I’d recommend both with those caveats. The new kid on the block I’ve been researching is Patreon. It’s a subscription service and you pay either monthly or per post. You have to have reasonably substantial content on a regular basis for people to pay a monthly fee, but Patreon lends ongoing support, not only financially but as a publisher. Personally, I’ve never treated my creative work as an option. Since my early teens, I’ve approached it as work, no conditions. There’s a lot of pressure, it’s more stressful than I would like, and I think that’s what drives a lot of people away. They like to just enjoy art and hopefully someday it makes money, but for me that’s a foreign idea. I never made art only for fun. I definitely liked it better when it was just for fun, but it was never done with only that intention. It’s always been art and commerce. It’s a tougher road, but it’s the only way to go if you want to do it all the time. TA: You began freelancing at Marvel Comics in the early 1990s, a period when the company kept its doors—though not so much its mind—open to new artists and new characters. How did this working environment help you become the artist you are today? SS: Marvel was hunting for young talent. They’d done really well with people like Rob Liefeld and Todd McFarlane, and when I came along, those guys had just broken off to start Image Comics. I think Marvel liked a young person coming in who was more malleable and had less ideas about what they wanted to do. I didn’t fit that profile, which is why there was friction. They wanted fresh blood in theory, but in reality they didn’t want to change how they did things. They pushed more toward action sequences. Every time I tried to have a conversation, I’d be told I didn’t know what I was talking about. One of the problems that came up was with the first issue of Saint Sinner. They stuck gimmicky foil embossed covers on it, and I had a series of arguments with editors about how this wouldn’t attract a dedicated readership. They told me not to worry, we know this’ll work. Almost a year later, I received a gratuity cheque for four thousand U.S. for the sales of Saint Sinner #1. Then, six month later, I was working on a job I hadn’t been receiving cheques for. When I called Marvel accounting to see what was up, I was told I owed them money. It turned out that the gratuity cheque, which was given out based on issue sales, had been pre-emptively sent to me, and all of the newsstand copies of Saint Sinner #1, which are returnable, were returned. Marvel decided I’d been erroneously paid these gratuities and was clawing them back without contacting me. I ended up swearing off working for the company until the early 2000s when Joe Quesada came in as Editor-in-Chief, though it was still a very top-down environment. TA: You’ve collaborated with some great writers over the years—with Rick Remender and Kieron Dwyer on Sea of Red, with Jim Munroe on the graphic novel Therefore Repent!, and with Ty Templeton on Revolution on the Planet of the Apes, to name three—what did these experiences teach you about your craft? SS: The main thing is problem-solving. On Therefore Repent! with Jim Munroe I did a lot of structural work adapting his writing, which was closer to straight prose, into a comics form. Myself and Mark Sable—the person I’m currently working with on Dracula: Son of the Dragon—we have regular back-and-forths about what works and what doesn’t, and I get a lot out of that. With other projects my say as an artist is limited to a set script and how I express it. What stands out and what I’m always hungry for are strong editorial relationships. A.J. Duric taught me a lot about writing. At Marvel, just before I stopped working there, I got some constructive feedback from Joey Cavalieri. I find them invaluable in terms of personal growth in storytelling. TA: Could you sketch out a day in your creative life? SS: Often I get up by responding to email and the feedback from stuff I’ve been posting on Sequential and social media. Then comes the morning coffee and I usually spend the first quarter of my day preoccupied with the scuttle work of self-publishing. The big thing I’m trying to get the hang of now is composing tweets that don’t sound repetitive and annoying. Most days I’m drawing, inking or working on layout pages, but each job has different demands. When I’m doing breakdowns, I’m very analytical going through the script to figure out all the shots, angles and rough compositions. On days when I’m pencilling, it’s a lot more fun but still very structural. Finishing is probably the most fun; I can see the end in sight and sometimes I’ll work really late, because if I do a little more, the page will be finished. In the end, I’m spending less than a quarter of my time genuinely being creative. TA: Book One of Dream Life: A Late Coming of Age, your first solo graphic novel, is about five friends’ search for identity in their late twenties and early thirties. They struggle, with varying degrees of success, to inhabit the middle space between how they view the world and how the world really is. In your own words, please explain your fascination with how people go about figuring out who they are. SS: The search for identity is a universal human experience. We’re all trying to figure out how we fit in the world, and whether or not there’s meaning in that is up to the person. In my own case, I’m know who I am on a gut level, comics is what I want to do with my life, but my comfort with where I am in the moment constantly changes. If it didn’t, life would be pretty boring. TA: In the afterword to Dream Life, you mention that empathy and active imagining are essential to understanding the characters’ emotions, most of which are expressed indirectly through actions and gestures. What’s the reasoning behind this narrative choice and what does it say about being an adult in the 21st century? SS: The former is a personal choice to do work that’s interesting to me as a reader. Many comics spell out feelings in text and explain more than is necessary to get at the widest possible audience, and I want to shift control of interpretation, or of the reading experience, back to the reader instead of hitting them over the head with characters’ internal states. Certain filmmakers influenced me too. Jim Jarmusch is one who talks about people’s thinking without rehashing it. You might get a hint or foreshadow for context, but in the moment you are just watching. With Forest Whitaker in Ghost Dog, for example, it takes a while to discover what his thing is. The joy of the story is finding out who he is, not having the story handed to you. In Dream Life I’m interested in finding a balance between an engaging story and one that’s a bit of a puzzle for the reader. I’m not sure about the latter part of your question, but there’s an easy assumption that this is a more mature way of telling stories, which I’m not comfortable with. It’s certainly more of a challenge and takes a more patient audience than one looking to shut off and watch a show, but that’s all by design. TA: In that same afterword, you say writing is more pleasant and less complicated for you than drawing. Could you elaborate on that? SS: I have less study about how to write than I do art. It’s a simpler process for me because the act of writing isn’t burdened with as many technical ideas. Also, mechanically, I can write a sentence, “A character walks into a room,” and it’s done. Drawing that involves thinking about what room, from which direction, what camera angle, lighting, the character’s anatomy, and you could keep on going. Drawing with intention for commercial art carries more constriction than there is with putting words on the page, because once you choose a style you can’t deviate from it. TA: When can we expect Dream Life Book Two? What can you share about it to hold us over until then? SS: You reminded me of a David Lynch quote. There was this video of someone asking him to talk about one of his films, and he said, “I hate talking about a film, that’s what I made the film for.” I’ve been trying to not say much about the story in Dream Life because the book is so character-driven. In Book One we get to know this group of friends and the conflicts in their lives, whereas in Book Two their storylines collide. You’re going to see what happens to Charlie and his dog Scrappy. I’m getting tweets now saying, “Please don’t kill the dog!” I wonder how many people noticed that box in the car P.J. gets into. That’s kind of important. My hope is to begin art for Book Two in early 2015. SALGOOD SAM'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed