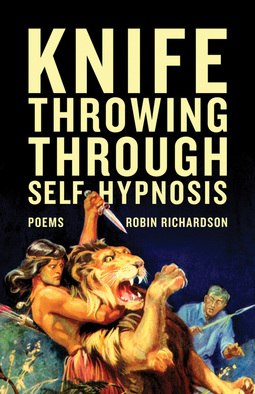

RUSTY TALK WITH ROBIN RICHARDSON Robin Richardson Robin Richardson ROBIN RICHARDSON is the author of Knife Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis and Grunt of The Minotaur. Her work has been shortlisted for the Walrus Poetry Prize, CBC Poetry Award, Lemon Hound Poetry Prize, and ReLit Award and has won the John B. Santorini Award and the Joan T. Baldwin Award. Her work has appeared in many journals including Tin House, Arc, The North American Review, and Hazlitt of Random House and is being interpreted into song by composer Andrew Staniland for the Brooklyn Art Song Society in New York. She holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and BA in Design from OCAD University. She resides in Toronto. Richardson’s latest collection, Sit How You Want is forthcoming with Signal Poetry. There’s no flirting here, no hinting at a thing [...] There is blunt exploration of the subjects I have been working my whole life towards the ability to clearly express. Whiskey Blue: How was Sit How You Want born? I want to know how you conceived of your latest collection, the origin story if you will. Robin Richardson: First off I want to thank you for taking the time to read the book and for asking questions I’m excited to answer. Okay, so Sit How You Want came to me the same way almost all my projects do. A few strong poems come first, then the realization that I’m on to something I want to pursue, followed by a close examination of the themes and tone, central preoccupations of the poems. They point and I carve a path from there. I had moved back to Brooklyn for a spell and was sharing an apartment with a friend from grad school. I was very happy, and very single. My energy levels were through the roof. I’d stay out late exploring every inch of the city, experiencing as much as I safely could. A lot of these experiences had to do with men, whom I was very much eager to dissect, to fully realize my relationship to power-wise. I was getting messy, making mistakes, and learning. After these late nights, I’d wake up early, as is my routine, and write for about five hours at the only café in our rather off-the-beaten-track neighbourhood. That’s when I wrote the poems that launched Sit How You Want. The first few poems I wrote for the collection were “Earthquakes Are My Favourite Way to Make Islands,” “This Year’s Going to be Different,” “Sushi Date,” and of course, “Sit How You Want, Dear; No One’s Looking.” These poems told me what I wanted to write about: sex, power, anxiety, and the shifting relationship I as an individual had with all of the above as I moved through my experiences towards understanding and inner strength. All of this is set to the backdrop of a world of anxiety and terror; broad-scale issues surround the speaker in the poem as she moves through intimate preoccupations. I don’t believe one can learn what it is to occupy one’s self as a human without having been broken a little, having struggled through the darker, more difficult elements of being alive. WB: Sit How You Want is your third book. What can you tell me about the experience of writing your first book--The Grunt of the Minotaur—and your second--Knife Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis—and your latest? Has your process changed? Have your expectations changed? Does it get easier from one book to the next? RR: Each book, and likewise each experience, was so vastly different. Grunt of the Minotaur was about learning to use language. I still hadn’t reached the level of craftsmanship and philosophy to perfectly merge the two, so what I did instead was explore a small inner world with a music I was just learning to make. It was fun and free in that regard, more concerned with experimentation and beauty than anything else. Knife Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis was my thesis at Sarah Lawrence College. It is a dense grab bag of every influence and preoccupation I had at the time, which was a lot. The world was rushing towards me at an alarming rate and Knife Throwing was my way of wrangling it all into something tangible, sharable. Sit How You Want is the first collection that succinctly explores a personal theme through progression. In this regard, it is the most exciting and most terrifying collection of the three. In terms of shifting expectations and levels of difficulty, I’d say it gets more complex and requires more as I go, but that’s because I’m becoming capable of more. In this regard, I can’t say it gets more difficult or easier. I work as hard as I can every year, and every year that capacity is simply greater. WB: Looking at Sit how You Want, how would you characterize your greatest departure from Knife-Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis? RR: A friend of mine, and fine poet, Michael Prior, said it best and I’ll paraphrase him here. In Sit How You Want, he said, “the aviators come off.” There’s no flirting here, no hinting at a thing as there often was in Knife Throwing. There is blunt exploration of the subjects I have been working my whole life towards the ability to clearly express. WB: How would you describe your selection process? How do you choose which poems make it into a collection? How do you curate your own work? RR: At this point in the game, my focus and level of preoccupation with the project itself leaves little room for unrelated or weak poems. I am obsessive and won’t produce anything that doesn’t work fully towards the end I envision. There is, however, a large document on my desktop called Scraps filled with bits and pieces I feel are strong but haven’t been able to incorporate into a working piece. They get pillaged now and again, some get turned into a side project I have of illustrated lines called Daily Creations. Some merely sit in that document destined for deletion. WB: How long do you typically spend working on a collection? RR: I’d say two years to get the meat and another year or so to tinker after the publisher takes it on. I’ve become skilled at being poor so that I rarely have to take on a full-time job. This means that during those three years I clock a minimum of four, often many more, hours a day towards writing and research. WB: What’s your writing process like? Morning writing and black coffee; afternoons and herbal tea; late nights with a whiskey? RR: Coffee is a great aid as are crowded public spaces and warmth. As of February of this year I’m no longer a whiskey drinker, or a drinker of any alcoholic beverage for that matter. The changes this abstinence, along with a spiritual practice, has brought about have been miraculous. WB: The tone of Sit How You Want is just pitch-perfect! How do you do this? How do you imagine then execute tone? How do you make it consistent? Where does this seedy, fleshy, Tom Waits-quality come from? If I’m misrepresenting the tone, please feel free to debunk. RR: Thank you! I imagine it’s a result of the themes I’m exploring here. Sex and power harken back, for me, to old film noir and pulp novels. In “Day Noir,” in particular I take on a really pulpy tone. It’s meant to reflect the way the hapless heroes of noir dictate their own impossible circumstances by adapting these removed tough-guy personas in order to combat perhaps the inevitable powerlessness of their situations. I move from this nihilistic noir to the posturing bravado of rap stars as my relationship with power shifts in the collection, growing out of one affectation into another in order to grapple with delicate revelations without fading away into that delicacy. WB: What are some images and ideas you find coming up over and over in your work and imagery? RR: There are a lot of disasters: plane crashes and automobile mishaps, derailed trains. The book is about getting somewhere and getting there in a convoluted, danger-filled way. Terrorism plays a role in there too, as do dangerous men, and frightening sicknesses. I’ve basically booby-trapped the book so that the reader must constantly be on guard. Sex, of course, comes up a lot, mainly because I find it inevitable in the discussion of power and in life in general. Also, oddly, there are a lot of Sundays. WB: I was enchanted by the poem “Eventuality.” There’s burlesque, “there’s bending over for a man who makes believing hot,” there’s a naked narrator lying on the couch next to whoever the poem is addressed to. Who is the “you” in “Eventuality”? How does this moment of nakedness on the couch overlap with sex, performance, power? RR: That scene in “Eventuality” is a pretty big key into one of the underlying preoccupations of this book: to procreate or not to procreate? The “you” in the poem is a meekly disguised “I”, too afraid to admit that it’s the subject of the poem until the final stanza. It’s a disorienting gimmick, I know, but the other possible interpretations of it, that the you and I are this basic interchangeable female archetype, is also more than welcome and somewhat intentional. I think it’s a great thing when multiple interpretations and functions coexist. That’s one of the rare capacities of poetry and should not be shied away from in an attempt at having complete control over a reader. WB: In “And no, we don’t go easy,” the final two lines read, “The wars / are so damn civilized these days.” Can you talk to me about this? The line really struck me. RR: Yeah, that’s a big part of the book too. Sit How You Want is in a lot of way about the conflict between primal instincts and emotions: rage, fear, lust, etc., and the “civilized” world we are being asked to function within the confines of. Another poem reads “We fight classy like the queen fights her pneumonia”. I imagine the poems as the wild inner life of this heavily adored, closely monitored queen who must repress her nature in order to maintain the efficacy of her role in the public eye. We, especially in North America, live in a culture of restraint. Sex is to be reserved for love and commitment, anger to be held in or excised in journals or at the gym. We fight literal wars with drones, safely distanced from any empathy-inducing proximity to those we are fighting. We declare our feelings via text message and email, avoid eye contact. We are told to have control, conceal our vulnerability, downplay pain and fear. I don’t believe we were designed to hold so much in. We are animals and for several reasons, many of which admittedly make good sense, we make a conscious effort to escape our animal instinct. But repressing a thing doesn’t make it go away. With this book I chose to exorcise the demons. I get naked and a little dirty, roll around in the muck. WB: In “Always end up trusting Cary Grant,” a line reads, “I’m addicted to discomfort.” What I know about Cary Grant is that he really went from rags to riches in the classic American way. I’m curious if this informs the line. Can you speak to the overlap between discomfort/displacement and success in the creative arts? Again, if I’m inferring erroneously, please debunk! RR: That’s an interesting theory, but the Cary Grant connection to the idea of discomfort comes less from his biographical self and more from the function his characters generally play in relation to his female counter-parts. He is always the suave, smooth talker who plays across über women like Katherine Hepburn, Sophia Loren, Ingrid Bergman, Rosalint Russell, and so on. In almost every one of these films, he slowly woos the woman toward her stronger self. It’s an uncomfortable process, and I’m constantly at odds with the way these films work. While it’s thrilling to see women coming into their own, taking the reigns at the newspaper, or throwing caution to the wind to have a wild affair and dodge what would have been a crippling marriage, it’s always under the persuasion of the ever-manipulative Cary Grant. I’m so conflicted. It’s the same in so many of the poems: the lessons learned, the growing done, is through the filter of experiences with men, for better or for worse. In the past few years I’ve really moved away from this dynamic, which is difficult in a world written and directed primarily by men. The trick now is to seek out works for and about women who come into their own on their own. I’m thinking of Broad City, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Volver and so forth. Cary Grant can be a good influence, but he is always acting in his own self-interest and that’s far from ideal. In the world my poems aspire to women come into their stronger selves unaided by blokes like Grant. WB: There’s a brusque humour in a lot of your work. How important is it to you to write funny? RR: The humour provides a necessary balance. I find most of the subject matter of this collection to be scary and difficult. As a magic realist writes in plain language so as not to overdo the disorientation effect, so must a poet dealing with serious subject matter lightens her load with humour. The fool gets away with sharing truths not even the highest of advisors do. This is because the fool stands in pitiful territories, saying, “here are the facts, they are absurd and you have the option to take them to heart or laugh them off as the absurdities they are.” If you tell someone what to do her impulse will be to rebel. However, if you show her what to do, humorously, in the fashion of Cary Grant, she is likely to adapt the idea as being entirely her own and go along with it. God, I sound manipulative here, but that’s the job of the poet, to infiltrate the readers mind and take effect. WB: Sex and sensuality are prominent characteristics of your work. How important is sex in literature? In your work? Is it powerful? Is it taboo? Is it just another part of life that I’m needlessly calling attention to? RR: It’s like I said in regards to civilized wars: I think sex is this really big part of who we are and what we want as animals and is too often overly controlled or repressed. I, in this collection, refuse to exercise restraint when it comes to subject matter. I think about sex, I partake in it, therefore, I write about it. There is this trend in poetry, especially in Canada, to choose subject matter based on fashion and political correctness. I think this tendency has a crippling effect. The point of poetry is to strip away the bullshit and show what it is to be human, whether to be related to or to expand empathy, combat madness through exposure of one human to another. If you’re going to veer away from your truths in favour of fashion, or be driven by a fear that your preoccupations will be judged, found offensive or lame, then you may as well stop writing. False writing can be mediocre-to-interesting at best. Do we really need more of those qualities in our art? WB: The titles of your poems are extremely striking and imagistic. How important are titles to you? Do they come easily? RR: Thank you. Titles are tremendously important to me. They’re the backbone of a poem really. I’m always amazed at how often the possibilities of titles are overlooked. A title is like a face and should be as telling about the nature of a poem as a human’s face is of her nature. I wish I could describe some painstaking process by which I come up with my titles, but I’d be full of it. They come very much instinctively after the writing of the poem as if divined and I’m happy enough not to ask too many questions about that particular gift. WB: What’s your greatest obstacle when it comes to writing? What demons try and keep you from sitting down and filling blank pages? RR: Again, I wish I could say here that there is a great struggle, but in truth there is very little that keeps me from the page. I love the act of writing. It’s better than sex, food, sleep, dance. I look forward to it every morning when I wake up and think about it as I fall asleep. It’s what lends structure and meaning to my life and is in no way a slog. I don’t want you to get the idea here that it’s easy. It’s incredibly difficult and often leaves me drained and very much in physical and mental pain, but I love that about it. I love the battle and the battle wounds. WB: Who do you read for inspiration? RR: The two poets whose works I went to again and again while writing this collection were Robert Frost and Frederick Seidel. You’ll find a lot of Frost in the collection in particular. Outside of those granddads, I focus on a lot of female poets and writers like Louise Gluck, Angela Carter, Virginia Woolf, Mary Ruefle, Susan Sontag, Flannery O’Conner, Emily Dickinson, Leslie Jamison, Tavi Gevinson and so forth. WB: What should readers expect from your new collection? RR: In Leslie Jamison’s Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain, she exclaims to her therapist in the midst of a breakthrough, “My wounds are fertile!” Sit How You Want is a documentation of the creation, conquering of, and ultimate fertility of gaping wounds. It’s about being broken in order to rebuild better. It’s about way power develops through powerlessness. Readers can expect discomfort and disorientation. They can expect a psychological narrative that strengthens as the collection progresses towards a state of freedom. There is nothing safe here or consoling. I don’t pretend to have any answers but rather open the lid on the world as I see it and dissect it in intimate high-def. WB: Do you have any writing rituals? Superstitions? RR: Not really. I believe in hard work and tenacity. I think self-examination is crucial, as is participation in and curiosity about the world around you. I do spend a lot of time watching music videos and indulging in the feelings they give me. I feel I learn a lot about my own emotional responses and priorities this way. Lorde got a lot of play during the writing of this collection, as did Rihanna, Beyonce, Lykke Li, Madonna (80s), and Sia. I try to stick with women who are either candid about their emotional experiences or unapologetically grandiose in their presentation of the self. They all informed the collection. WB: I was hoping you might tell an anecdote about growing up with a pool shark mom and a gambler dad. Can you share? Am I misconstruing your mom or your dad’s work? If you care to share a story (I feel like this relates to the honkytonk quality I was describing, and the rich sense of place that colours many of your poems, so that’s why I’m reaching. If you don’t want to go into this, please feel free to overlook. The same goes for any questions you don’t care to answer.) RR: You’re not too far off, though my mother moved from billiards to law and is now a part time judge in small claims court. I feel like, for her sake, that needs saying before I go on with the anecdotes. Most of the tone and setting of the book, particularly in the beginning, can be attributed to my father. The poems “Woodbine by the 401” is fairly literally about my weekend outings to the racetrack with him when I was a kid. I spent a lot of time in pool halls and on road trips, learned to bluff well and read someone’s best attempt at a poker face. There was much talk of how to pull off a good hustle and what it took to be better than or at least more strategic than any given opponent. I spent more time with pool sharks through my early teens than I did with other children and imagine that had a lot to do with how quickly I gained insight to the world of a particularly left of centre side of adulthood. WB: What is your first memory of writing creatively? RR: The first creative writing assignment I remember was in grade two. It was Halloween, and we were asked to write and illustrate a poem about some seasonal object. I wrote a pumpkin poem in the style of Blake, unknowingly I believe. It went something like “Pumpkin, pumpkin burning bright,” and so on. I fell in love with the process instantly and knew I wanted to work with works and music for the rest of my life. Ironically, I failed that year of school and was shortly after diagnosed with dyslexia. It would be another six years or so after that before I could properly read or write. ROBIN RICHARDSON'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed