RUSTY TALK WITH PAUL DUTTON

This communication was conducted by email between John Nyman and Paul Dutton. John Nyman: At Rusty Talks we often ask writers about their first memory of writing creatively. Your career, however, has focused at least as much on your signature oral performance technique of “soundsinging” as it has on “writing” in any traditional sense, and you have said on several occasions that you see your work as “a continuum; pure music at one end of the spectrum and pure verbality at the other end” (Somerset). Considering this, what is your first memory of engaging in any creative activity, whether musical, verbal, visual, or something in between? Paul Dutton: In my preschool years, when I got pissed off about something, I’d stomp up the stairs, blistering the air with the foulest language I knew: “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Stinkers and Bums!” That, at any rate, is how I have always remembered it, but my eldest sister recently insisted, quite adamantly, that what I shouted was, “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Bums and Stinkers!” And that has made me wonder if I perhaps reconstructed, from abiding family lore, my personal memory of my oft-repeated display of pique, complete with a mental image of my miniature self pounding up the staircase. Whether the memory I hold is truly mine or borrowed from accounts heard from family members, it’s clear that, somewhere along the way, I exercised a bit of aesthetic initiative, reversing the last two terms to create a skippier cadence. JN: What would you say are the similarities and differences between your sound performance and your written work? PD: Oh shit, I don’t know . . . [3 days later (because let’s admit it: I’m writing this, not speaking it)]: Okay. I’ve thought a lot about this. First of all, my work doesn’t in fact readily divide into “sound performance and written”: there are all kinds of gradations and overlaps. As well, there are plenty of similarities and differences within those two categories, not just between them: for one thing, I write print poems in no one style but throughout a wide range, including formal, free verse, minimal, narrative, with line breaks, run-on, found poems, etc. My sound poems range through a variety of styles as well. And then there are the visual poems, which are arguably as much drawn as they are written—if typing a bunch of punctuation marks, as in my Mondriaan Boogie Woogie sequence (two of which appear in Sonosyntactics), can even be called writing. I like to refer to the whole field of visual poetry as “drawing with the alphabet.” So, we’re getting into distinctions and categorization here, which always make me feel uncomfortable. In so much of my work—and in almost everything else in the world—categories overlap or merge. Anyway, there are no consistent similarities and differences between my soundworks and poems for reading (to substitute terms for your two categories). I have linguistic and non-linguistic poems in both of those categories. I have sound poems with words and fluid syntax, and “written works” with no words (single letters or phonemes instead) and fractured syntax. A number of poems fall into both of your categories, some with performance notes, some without; and some whose written versions have shortened passages of what would be extended repetitive material that works fine in performance but would be oppressive in print. Since the late 1990s all my newly created soundworks have been totally improvised and almost exclusively nonsemantic, unlike the painstakingly worked-over poems composed for reading and recitation. I still perform repeatable repertoire works, which are likewise worked over, but I have long since stopped producing new works in that mode. One consistent feature across the various categories that can be applied to my creations is that the individual works proceed out of themselves: I begin with some generative notion—a word, phrase, image, sound, whatever—and find my way by following the poem (or fiction), sensing its direction and development rather than imposing any preset idea of where it will wind up. In a pure-sound improvisation I of course move more rapidly through the process than when I’m working over something in a repeatable form. Another consistent feature is concentration on the sonic qualities of language and of human utterance in general. This is reflected in the titles I’ve given some of my books (Sonosyntactics, Aurealities, and Right Hemisphere, Left Ear) and my two solo CDs (Mouth Pieces and Oralizations). JN: How do you convey your creative efforts to the listener/reader when you have access to only one medium or the other? PD: I’ve partially answered that already in the third and fourth paragraphs of my response to your previous question. Some of my sound poems are thoroughly worked out—what in music is sometimes referred to as “through composed,” though that typically means notating pitch, rhythm, phrasing, dynamics, and tempo, whereas I never specify pitch, rarely specify volume, and generally, both in sound poems and poems specifically for the page, leave various of those elements to be inferred, implying them by punctuation, line breaks, and distribution of the text over the page. I’ve one printed poem for which I’ve provided idiosyncratic diacritics, briefly explained; and several for which, as already stated, I’ve provided explicit performance notes. JN: You often write about numbers—not mathematical equations, but numbers as quirky and surprising participants in dramatic situations. Why this fascination with the numerical? PD: Maybe its compensation for my general innumeracy. You know, a fascination with one’s disability, or an obsession with an unrequited love. JN: Your work contains many poignant references to time, especially in relation to performance and the body. For example “Milk-Cart Roan” opens with breath breathe JN: How does the idea of time connect, or differentiate, the kinds of writing and genres of artwork you engage in? PD: Hmmm. Time. Well, my readings and my musical performances of course operate within time constraints, either very tight (“No more than five minutes, okay, Paul?”) or very loose (“Take as long as you want”). Does that qualify as a connection? Well, here’s a for-sure differentiation: improvised soundworks are created within the time it takes to perform them, but a poem (whether a sound poem or a conventional print poem) that took me months to compose can be read in a matter of minutes or even seconds. And then there’s content: an awful lot of my bookable poems deal with multiple aspects of time, either referring to or reflecting on various temporal conundrums, ambiguities, possibilities, illusions, and incongruities, among other time-related phenomena (like memory, for example). I’ve got a semantically based sound poem entitled “Time” that starts out with that word and moves through a developmental process to arrive at the word “untime”—which is another obsessive notion for me. But I’ll be damned if I can see a way to get any of that kind of content across within a nonverbal sound improvisation. JN: Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry of Paul Dutton is the newest entry in the Laurier Poetry Series, collecting some of the best poems from your nearly 50-year career with an introduction by Gary Barwin and an afterword by you. How did Sonosyntactics come about, and what did you hope to accomplish with the collection? What was it like working with Barwin (who also selected the collection’s poems)? PD: It’s an invitational series, initiated by the publisher or an independent editor, and Gary proposed it to Laurier—without my knowledge, of course, sparing me the disappointment of a possible refusal. Both Gary and I wanted it to be a collection that fully represented the multimodal character of my work and we’re both satisfied that it is. The concept of the series is to present 35 poems by any given author, which we considered unworkable at the outset, so just went our merry way but kept it within range of the more-or-less average page count in the series. I mainly left it up to Gary to choose, but twisted his arm over a few poems I felt had to be in there for one reason or another. He has either a supple arm or a high tolerance for pain, cuz he didn’t cry out too loudly. To switch the metaphor, we saw eye to eye on almost everything. JN: For me, one of the most striking parts of Sonosyntactics is “Lines on a Line of Kurt Schwitters,” a multidirectional matrix of typewriter lines riffing on Schwitters’s “Decide for yourself where the poem begins.” The collection as a whole presents us with a variety of reading challenges whose solutions we do have to “decide for ourselves”: branching paths nested in long footnotes (“Uncle Rebus Clean-Song”), extremely dense and repetitive prose (“A Little Light Love,” “Thinking”), and performance notes far longer than the “poem” they annotate (“Mercure”), to mention just a few. What role does choice play in your writing, both for you as a writer and for your intended or imagined reader? PD: A choice I make with each poem I write is to compose it either with line breaks or as run-on text—what is usually called prose poetry, a term I frankly find pointless. I myself would never designate such works as “A Little Light Love” or “Thinking” as prose. They are poems, plain and simple, and a qualifier such as “prose” is neither necessary nor helpful. Surely what makes a literary work poetry is the character of the writing, not the way the words are laid out on the page. There’s an awful lot of prose getting published that’s written with line breaks. Writing is, of course, very much a matter of making consecutive choices, either instantaneously or over the course of minutes, hours, days, even years. Yeats somewhere (in a poem, I believe) characterizes poets as staying up all night in pursuit of a single word, which is a circumstance I can relate to. Even in this little exercise, I’ve gone back and forth between alternate words or phrases, or else have revised words or passages that days later I found unsatisfactory for one reason or another. As for the reader’s part in this equation, well the first choice is, obviously, to read or not read the material at all. Then a reader can choose to read silently or aloud, to imagine or attempt a performance of poems I’ve provided descriptive notes for, to heed or ignore my line breaks, to interact creatively with the text or let the words glide past, and in the case of “Uncle Rebus Clean-Song” to read the first thread straight through or else wander off down one of the side-trails. I wish I’d not used footnotes for the various narrative branches in that little fiction (which I don’t actually consider to be a poem, by the way), because the footnote implies a secondary status. Nichol used a more satisfactory method in The Martyrology Book 5, where superscripts offer the option of turning to another section of the book in the same font size, so there’s no hierarchical implication. JN: “The Eighth Sea” stands out in Sonosyntactics, both for the range of its performative strategies (from matter-of-fact cataloguing to full-on improvisational soundsinging) and for the political force of its themes: colonial violence, environmental destruction, and the collision of settler and indigenous languages in the Great Lakes region. What do you think the creative techniques you have pioneered throughout your career can contribute to deeply political conversations such as these, both in Canada and abroad? PD: Yikes! I’ll have to leave that for others to say. I do know that my good friend John Beckwith adapted some of the devices used in “The Eighth Sea” for structuring his 2015 oratorio Wendake/Huronia, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Champlain’s arrival in Huronia. I can’t imagine how to calculate the effect such works might have in the social or political spheres, but I suspect that it’s not significant. I prefer direct activist involvement as a more effective and appropriate avenue of influence in those areas. I’m not a fan of what I call propagandart—didactic or utilitarian works—however much I might applaud and revere the causes espoused. I’m out to create, not preach. I prefer to leave any political stances implicit in the artwork, and focus my attention on the aesthetic and spiritual realms, aiming for a subtler influence, more at the level of principle than of advocacy—you know, leading the horse to water and letting it drink or not (aha! another choice for my readers to make). JN: What are you working on now? Where do you want to take your creative practice in the future? PD: The immediate thing I’m trying to get to amid the welter of clerical tasks I have to fulfill in getting my work out either through publication, recording, or in-person performance, is a follow-up to Sonosyntactics, entitled The Poet’s Revenge: UNselected Poetry of Paul Dutton, which will consist of poems excluded from Sonosyntactics , but that I think are worth having out there again. Next will be organizing into a new collection the print poetry I’ve written since my 1991 collection Aurealities. And I’m hoping to, along the way, get my teeth into some fiction that’s struggling to the surface from somewhere within me. And then there’s my soundsinging, solo or in collaboration. My main band, CCMC (the initials stand for whatever you’d like), continues to play within and beyond Toronto. And I’m pursuing concert opportunities for two or three duos I’m in with instrumentalists. Source: Somerset, Jay and Paul Dutton. “Towards the Ineffable: A Conversation with Paul Dutton.” Musicworks 99 (2007). 30-37. <http://doyouconcur.com/articles/PaulDuttonMusicworks.pdf> PAUL DUTTON'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

| Description from the publisher: Sonosyntactics introduces the reader to over forty-five years of Paul Dutton’s diverse and inventive poetry, ranging from lyrics, prose poems, and visual work to performance texts and scores. Perhaps best known for his acclaimed solo sound performances and his contributions to the iconic sound poetry group The Four Horsemen, Dutton is a surprising, witty, sensitive, and innovative explorer of language and of the human. This volume gathers a representative selection of his most significant and characteristic poetry together with a generous selection of uncollected new work . Sonosyntactics demonstrates Dutton’s willingness to (re)invent and stretch language and to listen for new possibilities while at the same time engaging with his perennial concerns—love, sex, music, time, thought, humour, the materiality of language, and poetry itself. |

A Little Light Love

RUSTY TALK WITH FRANCISCA DURAN

Francisca Duran

Francisca Duran Michael Vass: When did you first become interested in filmmaking? What were your first films like?

Francisca Duran: I became interested in making films at Queen’s University, which has a film studies program with some production courses interspersed throughout. It was the late 80’s, and I remember looking at a lot of Canadian and American experimental and documentary work, as well as more expressive European and American fiction films. We were encouraged to be very open in our approach to making films—I don’t remember being taught a lot of conventions to follow, or if we were, I did not feel compelled to follow any.

In 1991, during my last year at Queens, I made an experimental documentary called Tales From My Childhood on 16mm, which recounts my family’s flight from Chile after the 1973 military coup led by Augusto Pinochet that ousted president Salvador Allende. Visually the film is made up of images of daily life, mundane images of Kingston, Toronto, and a trip I took with my family to Chile, as well as optically printed found footage from the time of the coup. The soundtrack is composed of memory fragments and stories. The visual and structural style references the work of Phillip Hoffman, Ann Marie Fleming, Patricia Gruben, Mike Hoolboom, Barbara Sternberg, Midi Onodera, filmmakers whose work I was drawn to at the time.

Tales has a companion piece, Boy, from 1999. It’s an autobiographic piece about the visual poetics of Vancouver and the birth of my first son. The film was shot on 16mm and contains optically printed footage of Vancouver and of Jacob’s birth. I also made a couple of found footage films taken from 1980’s movies directed by women, She Was So Young Back Then and Does This Mean We Are Going Together?

My films are sometimes autobiographical documents and they always (attempt to) explore the intersection points between memory, history, and technology and how these relate to the media that represent them.

MV: What led you to make a film about Thomas Edison with Mr. Edison's Ear?

FD: I set out to make a documentary about some early wax cylinder recordings of aboriginal voices that the ROM had but that belonged to the Six Nations reserve. The ownership and copyright was being negotiated to the point that the ROM was only allowed to display the wax cylinders, not play the audio. It became clear very early on in the research that making this film in the way I wanted to was going to be very difficult because it would involve mediating interests between the ROM, the Reserve and me.

While researching the Six Nations cylinders, I investigated the mechanics and history of the early phonograph and became fascinated by the simplicity of that machine. I am always interested in the tactile qualities of media that are thought of as ephemeral, and I want to give a graphical representation to what is perceived as invisible, for instance, light, sound and memory. Edison was actively involved in the development of early sound recording technology. While the history of the phonograph of course extends far beyond Edison, he does hold the first patent. I learned that Edison was (mostly) deaf and that became an important emotional through line for an exploration of the phonograph or for the impetus to capture sound, that Edison wanted to hear so he develops a way to hear (and to try to ruthlessly control the political economy of recorded music and possibly the world).

MV: What was the most surprising thing you discovered in your research?

FD: I keep coming back to the early paper film prints that the Edison Company made as a way of copyrighting those works. They are beautiful. I love that when these films are restored some of the “originals” are paper.

MV: Mr. Edison’s Ear is composed of numerous different formal elements--interviews, archival footage, archival sound recordings, animations, Edison’s diary writings. What was your process like as you assembled all of these elements?

FD: I made the film over three years, and I did not work from a script but rather from a series of idea-threads, which would have their own visual or aural treatment, and included animation techniques, layering, optical printing etc. Eventually these components were structured into a finished movie.

I think of Mr. Edison’s Ear as a bit of a ghost story. There are over 5 million pieces in the Edison archives. When I was making the film, I would imagine Edison wandering among these archival bits, picking them up, revisiting them, contemplating the bad (and good) he might have caused as he helped to usher North America into modernity. This thought helped me to shape the film.

Almost everything in the film has been downloaded from Internet Archives. I spent a lot of time looking at, reading and listening to archival material and also contemplating the technical make-up of the original, and of the archival “copy”.

The interviews with theorist, Lisa Gitelman; sound archivist, Robert Hodge; and scientist, Kenneth Norwich were shot on video and then filmed off the screen onto black and white 16mm or de-saturated to give them an archival feel.

The animated type sequences are excerpts are from a book I found called The Diary and Sundry Observations of Thomas Alva Edison. Apparently, this book is regarded as being marginal and irrelevant by Edison scholars.

Notes on Mr. Edison’s Ear – Proof

By Franci Duran

The video establishes the following:

1. Thomas Edison is deaf.

2. Thomas Edison wants to hear

3. Thomas Edison’s desire to hear led to the invention of the phonograph.

And,

4. Edison is a capitalist.

5. Control over sound establishes mastery over technology and commerce.

If we associate these,

6. Edison’s desire to hear is about regaining his body.

7. Control over his body is manifested by his efforts to capture and control sound.

And if we admit a measure of madness,

8. He wanted to take over the world.

This darker element comes to the forefront in the final scene, which shows the Edison film of the “man killing” elephant being electrocuted. It’s a brutal and disturbing ending, made all the more haunting by the fast that you decline to comment on it directly within the film. Can you talk about achieving this mixture tones, and can you comment on the choice to end the film with the elephant?

FC: I needed to convey specific historical, theoretical and technical information, and that is what the interviews do. The diary sections are my attempt to give Edison a kind of poetic or reflective inner life. The original book text was very wordy, and often humorous, more like the writing of Mark Twain. These type sections in the movie have been radically distilled, and I took many liberties when I edited it down. Theorist, Lisa Gitelman, told me The Diary and Sundry Observations of Thomas Alva Edison by Dagobert Runes can’t accurately be called Edison’s diary entries, rather they are a series of written observations made while Edison was on vacation in 1885. Edison didn’t keep a diary, except for the texts in Runes' collection, although apparently he did write many notes in the margins of his books. Much of the “information” within the observations is discounted by historians. Their “marginality” is exactly what drew me to them. The material was very different from other material I was looking at.

I love elephants. They have rich and complex social relationships and rituals within their herds, and very long memories. They are also physically large, heavy, and I think they move beautifully. Electrocuting an Elephant (1903) is a documentation of the execution of Topsy the elephant on Coney Island. Topsy was executed because she had killed one of her trainers and seriously injured at least one other. Topsy had been abused during her life in captivity and consequently mistrusted humans. Edison suggested that electrocuting Topsy was an efficient alternative to other methods suggested (such as hanging). Conveniently for Edison, it allowed him to prove the efficacy of his AC distribution system over his competitors (mainly Westinghouse I believe), and this is why the execution was filmed.

I wanted the ending to be "open" but I am always asked why I did not contextualize this footage, so perhaps it is too open. Metaphorically it functions as symbolic of the collateral damage of progress, of our entry into the modern condition, of the price of progress, the death of an era. It is also a tribute to Topsy, and to all the creatures and categories of people considered lesser by the people behind power structures, those making choices, decisions and how those decisions affect other beings.

The insects and animals represent that marginality that exists and rises to the surface anyway despite dominant discourses and power structures. An obvious analogy would be tiny plans that grow out of cracks in concrete surfaces. In addition to making a film about the emergence of early sound technology, I was interested in exploring what lies behind the desire to control nature, time and space (physical spaces). The mid 1800 to early 1900s was a time of great change, and transformed people's internal maps, the way people conceived of space and time and themselves within time and space.

MV: What are you working on now?

FD: I am finishing up a one year contract as Education and Outreach Coordinator at LIFT (the Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) and working on two projects:

Cold Food is an expressive documentary anchored around a book of poems written by my father, Claudio Duran, which was published by poet bp Nichol's press Underwich Editions in the 1980's. The film explores poetic typographic forms, the history of the representation of downtown Toronto, and the limitations of translation. Cold Food is a visual and aural collage consisting of hand-drawn illustrations, type, archival maps, original footage shot on 16mm and HD, archival recordings, sound composition and original interviews. (In post-production)

AK47 is the fourth film in a series, “Retrato Oficial”, all based on the legacy of Chile's former dictator Augusto Pinochet. The works are constructed entirely of archival elements including declassified CIA telegrams, found footage audio and images. This component explores the stories that surround the AK47 that was given to Chilean president Salvador Allende by Fidel Castro, and which Allende used to commit suicide on the day of the 1973 military coup. (In development)

MR. EDISON'S EAR BY FRANCISCA DURAN

32 minutes / experimental documentary, animation /16mm, DV / 2008

WATCH THIS FILM IN ISSUE 6 OF THE RUSTY TOQUE

Michael Vass is a regular contributor to The Rusty Toque.

Chelsea McMullan

Chelsea McMullan RUSTY TALK WITH CHELSEA MCMULLAN

Sarah Galea-Davis: How did you first get into filmmaking?

Chelsea McMullan: I don't think I've found a way to say this yet that doesn't set off my precocious detector, but I wanted to make films from a young age. There's no great story or anything, just a progression from my parents' camcorder to studying film at York University in Toronto straight out of high school. Part of me wishes I'd came to film later because I think it would have been great to study something like philosophy or psychology first. At the same time though, I still work with the same people I met in my undergrad.

SGD: Was there a writer or filmmaker that had a big impact on you?

CM: On a personal level Jennifer Baichwal has been hugely influential. I interned with her and her husband Nick de Pencier right out of film school and despite being a thoroughly wretched production coordinator/researcher, they've both been so patient and generous with me over the years. I was occupying a corner of their office rent-free for like four years. I used to sleep on their couch, in the editing suite, when I was up late writing a grant. Also they are fucking awesome filmmakers, and over the years I've been able to watch their process and learn from them, while deeply engaging with pragmatic, ethical, and philosophical issues around the films I'm making. My absolute favourite filmmaker is Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Hands down, end of discussion, to a very obsessive extent. A few years back in Berlin, I bought a book, which is comprised of a still image of every frame in Berlin Alexander Platz. It's like 50 lbs, and my baggage was obscenely overweight, but it was totally worth it. I would say it's one of my most cherished possessions. Actually, the mayor of the town I grew up in was his cousin. I asked him about it once, and he told me a wild story about spending time with Rainer. I think it was supposed to be a cautionary tale.

SGD: What is your favourite part of the filmmaking process?

CM: I find that I'm sort of anxiety ridden through the whole process. Though if I have to choose my favorite part, it is probably watching rushes. There is still so much promise and nothing has gone wrong yet, but you’re past the soul-destroying production hump. It's a nice purgatorial state before you have to pull your baby apart and sacrifice it to keep the gods happy.

SGD: What is the best filmmaking advice you've received?

CM: Once something really bad had happened to the main subject of one of my films. His wife had a horrible brain aneurism and was in the hospital. I was young, so I thought the film was over and was ready to throw in the towel. I phoned Jennifer and told her about the situation, and she was like "Chelsea, this is your job. This is what being a documentary filmmaker is." I've never forgotten that. The times it feels most difficult and awkward to shoot are the times when usually it is most important because those are the moments of people's lives that we don't really share enough. Also more often than not people want their tragedies documented. They want to feel like people are experiencing with them, that there's value in their loss.

SGD: Your work spans the genres of documentary and experimental filmmaking. Do you approach the writing/creation process differently when it comes to your non-fiction work?

CM: I never set out to make documentary, fiction, or experimental films. A subject just crosses my path, and I follow it down the rabbit hole. I also feel like my work usually sits in some space of hybridity. I've never sought out a subject for a film, it always comes to me, and then I just try to tell the story in the best way I know how. The genre, the length, the style for me are all dictated by the subject matter.

SGD: Tell us about your current documentary that is being released in November?

CM: The NFB hired an actual writer to explain it in a concise and inviting fashion. Know that it is a passion project that Rae and I have been working on for the past four years or so together. Rae is a good friend and this was an important project for me.

SYNOPSIS: MY PRAIRIE HOME

In Chelsea McMullan’s documentary-musical, My Prairie Home, indie singer Rae Spoon takes us on a playful, meditative, and at times melancholic journey. Set against majestic images of the infinite expanses of the Canadian prairies, Spoon sweetly croons us through their queer and musical coming of age. Interviews, performances, and music sequences reveal Spoon’s inspiring process of building a life of their own, as a trans person and as a musician.

TRAILER:

Jacob Wren

Jacob WrenPhoto by Brancolia

RUSTY TALK WITH JACOB WREN

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative?

Jacob Wren: I don’t know if I have a first memory. But I do know around age thirteen I started suffering from terrible insomnia. Some nights I didn’t sleep at all, while most nights I slept very little. And basically I just filled the endless, sleepless nights with reading and writing, for more or less ten years, until I realized that the simple cure for my insomnia was rigorous physical exercise. Still, to this day, I associate writing with the strange, hallucinatory state that comes from having barely slept for weeks on end, as a kind of unreal trance, almost like a dream. It was during those nights, lying awake, almost too tired to move, that I first trained myself to write.

KM: Why did you become an artist/writer and what keeps you going?

JW: To be honest, the only thing that has ever really interested me was art (in all its many forms.) I wish I could become interested in something else, since I feel, as a human being, at times this overemphasis on artistic interests makes me a bit narrow, as well as making my interactions with other people often rather difficult. (I mean, I do my best.)

At the same time, I find it very hard to maintain any interest in art and often don’t know exactly what keeps me going (except that I have no idea what else I could possibly do). Sometimes I remind myself a bit of this apocryphal story of a Russian who moved to New York but never learned English. Gradually, over the course of his life, he forgot how to speak Russian, yet still never learned English, so in the end he spoke no language at all. Gradually I am becoming less and less interested in art, while not really becoming interested in anything else, so in the end I’m kind of nowhere. Like a priest who has lost faith. But that makes it all sound more dire than it actually is. Still, I think it’s important that we talk about these things, since hardly anyone ever does.

I have often said that I don’t particularly relate to people who make performance, or write, or make art, but I do relate to people who make performance / writing / art who think about quitting every fifteen seconds. Those are really my people. I call us the ‘boy who cried wolf set’. Because, for me, if you really look at art today, at what it means, at who it reaches, at what is considered successful or important, it often seems like a complete waste of time. If I had any talent for it, or drive towards it, I would definitely quit art and become an activist, since the world’s problems are now so overwhelming, immediate and tragic. But, for better or worse, I can’t seem to get myself to do anything else: all I can really do is write. (Well, I also make performances, but that becomes harder and harder as the years roll on.)

KM: How would you describe your writing process? How does your blog A Radical Cut in the Texture of Reality fit into this process?

JW: I mainly feel like I don’t really have a process. I just have ideas and write them down to the best of my ability. Often I try to write every morning, but then, at other times, I am stuck for months on end and write very little. I usually do a first draft in a notebook, and then type it up as I go. Sometimes there is a little bit of re-writing as I type it into the computer, but mainly the second draft just allows me to think more about what I’m doing.

I definitely started my blog, in 2005, because I had almost completely stopped writing and was looking for a way to start again. It’s always been difficult for me to get published—I suppose what I write doesn’t quite fit anywhere (maybe it’s a little bit easier now, I’m not sure)—but at the time being able to just post what I was writing on my blog, as I went along, gave me more of a feeling that I was actually doing something. I would tell myself: just write one paragraph and post it, then at least you will have written one paragraph. It kind of made me feel like writing was possible again, after having felt it was basically impossible for many years. (Mainly due to too many rejection letters, or more precisely to the fact that I’m a little bit too sensitive to such things.) Now my blog gets about 2,000 hits a month, so that must mean someone is reading it, but I don’t really have any sense of who is reading it, why, or what they think. There are hardly any comments.

I spend so much time on the internet (mainly on Facebook and listening to music), and I know this has deeply affected how I think about art, about writing, and also how I practice it. It is difficult for me to really analyze what this change might be, it has all been so natural and intuitive, but I know there is something about the shuffle feature on iTunes, and about the seeming randomness as one clicks from one link to the next, that has been completely folded into my aesthetic.

KM: What or who influences your writing?

JW: I keep an ongoing list of favourite books: Some Favourite Books

And recently I have added a list of visual artists: List of Artists

But mainly I just want to devour everything. I want to have an overview. I want to know what is happening in art today, and everything that has ever happened in art before, and I want to use all of it while at the same time making it my own. I want to speak about the world, about the world today and about history, about ideas, thinking, philosophy, theory, and about my own subjective experiences. I want to struggle with it, admit to failure, be upset that I am not as good as the artists and authors I love but keep trying. I wish the mainstream was more open and more interesting.

KM: Can you discuss the relationship between writer and reader or audience? Who would be your ideal reader? I’m interested also in terms of your blog and its readership. Does that audience inform your work in any way?

JW: I have a sort of double life, half writing, the other half performing. When you perform the audience is right there in front of you, and all of my performance work is about trying to honestly deal with the fact that the audience is right there in front of me, about the paradox of trying to be yourself in the deeply unnatural situation of a room full of strangers watching you.

I’ve always like the Gertrude Stein quote: “I write for myself and strangers.”

When I was revising my last book, I showed it to a bunch of friends for comments, and I listened to all of their comments, and later, when the book came out, realized I had completely ignored basically all of their suggestions. I had asked for their help, and then completely ignored everything they said. (Well, I’ve always been stubborn.) And I feel this is so often the way between me and readers, I listen to every comment I get, think about it, try to take it in, fully absorb it, but never directly respond to anything anyone says. Nonetheless, I very much hope it is all in there anyway, somewhere in my head, affecting what I think, how I see what I’m doing, in some completely indirect way making the work better.

KM: What is the best piece of literary advice you’ve gotten that you actually use?

JW: As I’ve already suggested, I’m so bad with taking advice. But I really liked reading what Alain Badiou once said in an interview. He said the only rule for activism is: keep going. And I guess that’s mainly what I try to do now, keep going, which also means not making too many compromises, trying to offer up something different enough from everything else out there, trying to see the world a different way and put it into words. But, then again, I also constantly want to quit. Which is maybe why the advice is so important. Keep going.

KM: What is your favourite or funniest literary moment, if you have one?

JW: I actually can’t think of anything at the moment. Hopefully that means there are many favourite, hilarious literary moments to come. Maybe the future will be full of them.

KM: What are you reading at the moment?

JW: I just started reading The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal by Sean Mills. I believe I must be reading it because I live in Montreal. So far it’s fascinating.

KM: What projects are you working on in 2013?

JW: I am writing a new book entitled Polyamorous Love Song. Here is a short synopsis: It is a book of many different narrative through-lines. For example: 1) A mysterious group, known as The Mascot Front, who wear furry mascot costumes at all times and are fighting a revolutionary war for their right to wear furry mascot costumes at all times. 2) A movement known as the ‘New Filmmaking’ in which, instead of shooting and editing a film, one simply does all of the things that would have been in the film, but in real life. This movement has many adherents. Its founder is known only as Filmmaker A. 3) A group of ‘New Filmmakers’, calling themselves The Centre for Productive Compromise, who devise increasingly strange sexual scenarios with complete strangers. They invent a drug that allows them to intuit the cell phone number of anyone they see, allowing phone calls to be the first stage of their spontaneous, yet somehow carefully scripted, seductions. 4) A secret society that concocts a sexually transmitted virus that infects only those on the political right. They stage large-scale orgies, creating unexpected intimacies and connections between individuals who are otherwise savagely opposed to one another. 5) A radical leftist who catches this virus, forcing her to question the depth of her considerable leftist credentials. 6) A German barber in New York who, out of scorn for the stupidity of his American clients, gives them avant-garde haircuts, unintentionally achieving acclaim among the bohemian set who consider his haircuts to be strange works of art. And yet each of these stories is only the beginning.

And we are also beginning a new, ongoing internet/performance project entitled Every Song I’ve Ever Written. Here is a description:

From 1985 to 2004 Jacob Wren wrote songs. Lots and lots of songs. At the time not very many people heard them. Every Song I’ve Ever Written is a project about memory, history, things that may or may not exist, songwriting, the internet and pop culture. On the website everysongiveeverwritten.com you can listen to, and download, these songs.

In a way, because hardly anyone heard them, these songs don’t yet exist. If you are reading this, we would like you to consider recording your own version of one of these songs, changing it, making it your own, then sending it to us. We will post every version we receive.

There will also be performances and events. Solo performances will feature Jacob performing all of the songs in chronological order (it takes about five hours.) Band Nights will feature a series of local bands in different cities performing one of Jacob’s songs each. After each version, Jacob will interview the band about what it was like to cover the song, and the band will interview Jacob about what it was like to write it.

We are not doing this because we think these are the best songs ever (we hope at least a few of them are good.) We are doing this because hardly anyone heard them at the time, and we are wondering if there is some new, strange way to bring them out into the world. In doing so we hope to raise a few questions about what songs mean on the internet, about what songwriting is actually like today, and also take a sidelong glance back at the recent past.

LINKS

Radical Cut in the Texture of Reality

Every Song I've Ever Written

PME-ART

Tumblr

Goodreads

Le Quartanier

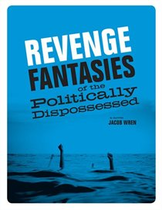

Pedlar Press, 2010

Description from Pedlar Press:

Set in a dystopian near-future, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed is a novel - a kind of post-capitalist soap opera - about a group of people who regularly attend ''the meetings.'' At the meetings they have agreed to talk, and only talk, about how to re-ignite the left, for fear if they were to do more, if they were to actually engage in real acts of resistance or activism, they would be arrested, imprisoned, or worse. Revenge Fantasies is a book about community. It is also a book about fear. Characters leave the meetings and we follow them out into their lives. The characters we see most frequently are the Doctor, the Writer and the Third Wheel. As the book progresses we see these characters, and others, disengage and re-engage with questions the meetings have brought into their lives. The Doctor ends up running a reality television show about political activism. The Third Wheel ends up in an unnamed Latin American country, trying to make things better but possibly making them worse. The Writer ends up in jail for writing a book that suggests it is politically emancipatory for teachers to sleep with their students. And throughout all of this the meetings continue: aimless, thoughtful, disturbing, trying to keep a feeling of hope and potential alive in what begin to look like increasingly dark times. Revenge Fantasies asks us to think about why so many of us today, even those with a genuine interest in political questions, feel so deeply powerless to change and affect the world that surrounds us, suggesting that, even within such feelings of relative powerlessness, there can still be energizing surges of emancipation and action

RUSTY TALK WITH LISA ROBERTSON

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative?

Lisa Robertson: I think my earliest creative acts were acts of deception and truth bending—petty theft, rebuttal, cover-up. This led directly to writing.

KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.)

LR: Everyday I sit in an armchair and write in a notebook as I read. If somebody gives me resources I leave the armchair and travel to read in an exotic library. Writing on trains and airplanes on the way to and from these libraries is a special pleasure, because so much anticipation and repletion is involved. Talking to my friends usually shows me how to work with the material I have gathered. My dearest friends are the ones I simply obey.

KM: How would you define experimental writing?

LR: I wouldn't define experimental writing. It would cease to be experimental then.

KM: What influences your work?

LR: Unanswerable questions. Unanswerable to me that is. Right now I am trying to understand the movement a triangle sections, and I am trying to understand the humoural system of medicine. Put more simply, desire influences my work.

KM: What have you read recently that excites you?

LR: I just spent a month reading at the Warburg Institute in London, for 6-8 hours a day, six days a week. Everything excited me. I was reading about the relationships between geometry, astronomy, optics, and medicine in the ancient world, until the baroque era and Johannes Kepler's work on the elliptical orbits. I wanted to understand the dynamics of the ellipse, and I wanted to understand science as a relational query into the structure of the cosmos, rather than a recitation of the mechanics of cause and effect. Plato's Timeaus is hallucinogenic in that respect. So is Kepler's The Six-Sided Snowflake. So is medieval Arabic optics. These studies are enticing me to draw more, and that is a pleasure.

In terms of recent poetry—Erin Moure's translations of Galician poet Chus Pato, Aisha Sasha John's new work, Angela Carr, the American poet Chris Nealon, and Francis Ponge. I read Ponge as a contemporary.

KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you've heard or been given that you actually use?

LR: Writing is the good use of boredom. I try to have a boring life. I don't socialize, and I eat nine servings of vegetables a day.

KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one.

LR: When Jam Ismael read at KSW in 2002 she sat a tape recorder on a windowsill and played a cassette recording of New Delhi crows. Vancouver crows came to the open window to listen and respond. Every emotion cracked open at once.

KM: What are you working on now?

LR: I am simply reading and learning, and making the occasional paragraph or drawing as record and exploration.

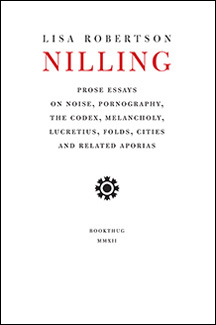

Nilling, Bookthug, 2012

Description from the publisher:

Nilling: Prose is a sequence of 6 loosely linked prose essays about noise, pornography, the codex, melancholy, Lucretius, folds, cities and related aporias: in short, these are essays on reading.

Excerpts from Nilling:

EXCERPT 1

I have tried to make a sketch or a model in several dimensions of the potency of Arendt's idea of invisibility, the necessary inconspicuousness of thinking and reading, and the ambivalently joyous and knotted agency to be found there. Just beneath the surface of the phonemes, a gendered name rhythmically explodes into a founding variousness. And then the strictures of the text assert again themselves. I want to claim for this inconspicuousness a transformational agency that runs counter to the teleology of readerly intention. Syllables might call to gods who do and don't exist. That is, they appear in the text's absences and densities as a motile graphic and phonemic force that abnegates its own necessity. Overwhelmingly in my submission to reading's supple snare, I feel love.

EXCERPT 2

In the facsimile Oblongus Codex, at the bottom margin on the page containing lines 1140-1159 of the fourth book of De rerum natura, I saw what at first appeared to be the photographed image of a small oval hole about the size and shape of my thumbnail, tidily cut from the vellum of the original. Bordering this ellipse, I saw a faint drawing that added a labial ornamental border around the shape. It seemed that some sort of monkish pornographic doodle had been censored. At closer examination I realized that the elliptical absence had in fact not been cut from the page by some historical censor--it was rather a flaw inherent in the structure of the vellum; the trace of a wound perhaps. Several of these photographed images of material mise-en-abimes appeared as I leafed through the codex. In each case the page was cut from the larger skin so that the scar found its place in a margin, so as not to interfere with the scribe’s work. But here in book four, the scribe had decorated the flaw in the skin with this mildly and endearingly erotic doodle. The tiny absence was animated: a lacework.

Photo by Joy Masuhara

time was sent 2 erth on first childrns shuttul from th at that time

trubuld planet landid in halifax moovd 2 vancouvr at 17 moovd

2 london wher i was part uv luddites alternativ rock band thn

toronto wher ium poet in residens at workman arts & recording

with pete dako wanting alwayze 2 xploor words n sounds n

image in th writing n painting showing paintings at th secret

handshake art galleree toronto most recent book novel from talonbooks

rusty talk with bill bissett

I asked bill bissett these questions about his writing process:

- What is your first memory of being creative—in terms of writing creatively or making art or music?

- Why did you become a writer and artist? What writers/poets/artists were influential to you when you first started out? Who are you reading now?

- Can you describe your writing process?

- Have you ever experienced a creative block and what did you do to get out of it?

- You work in a variety of genres and mediums, and your work has been described, among other things, as defying genre. How do you see your relationship between medium and genre in your work? Does the subject dictate the genre or vice versa? Or does it develop naturally?

- What are you working on now?

He responded by email over the month of September 2012:

dere kathryn th first 2 qwestyuns 4 rustee talk mor as it cums in

th first creativ work i remembr was in grade 3 or 4 b4 going in2 th hospital 4 a coupul uv yeers was a pome i wrote abt sail boats in th watr n th feeling in my brain n heart was veree thrilling 4 me an elixr reelee

thn a littul whil latr aftr mor thn a few operaysyuns i was in th oxygen tent n realizing i wud nevr b a dansr n or a figur skatr my first reel ambishyuns i cud write n paint i thot n that way feel th line mooving thru space n that way as well feeling th taktilitee uv life being physikal th enhansment from th abstraksyuns uv th skripts we wer ar all living thru i wrote my first storee thn in th oxygen tent wher i was deliting 2 drink orange crush n see th brite orange liquid cumming out uv my bodee immediatelee thru mor tubes i lovd that n that orange runway made me laff n feel veree poignant as well as my home planet lunaria was veree orange b4 all us childrn were remoovd from that troubuld planet n sent 2 erth

my first storee wch i wrote in th oxygen tent was abt a boy who didint want 2 follow rules n wantid 2 find his own way n swam out past th undrtow wch oftn was both a physikal risk n a metaphor 4 sew manee othr things in nova scotia n at great dangr he ovrcame th fors from th watr n made it 2 shore n thn vowd he wud dew it agen n agen sirtinlee if life wer as friabul as it seemd sew definitlee 2 b why not take th risk

my fathr had th storee typd out in several mor copees that was my first publishd work i feel veree warm abt him now in ths moment that he did dew that 4 me n evn tho i didint reelee start writing agen until aftr my mothr went 2 spirit evn a few yeers aftr that 16 n reelee agen full time until i got 2 vancouvr 17 my yerning 2 b always writing evr sins i was in th oxygen tent at 10or 11 has nevr left me

influenses medium genre hungree throat mor as it cums in

th subjekt 4 me is th genre n th genre is th subjekt iuv alwayze wantid 2 put books 2gethr that hold or contain diffrent genres as iuv also writtn pomes that contain difrent genres iuv oftn calld such pomes fusyun pomes my most recent work novel my first novel made me mor aware uv th medium is th genre n th genre is th medium n th medium slash subjekt is th genre mor aware thn evr how we write is can b what we ar writing abt mor thn an approach 2 mor thn creating th nuans uv it is th uv in my first novel calld novel abt 2 yeers ago brout out by talonbooks its a collagist work prob also calld post modernist in that th linear flow storee line is part uv th whol work is not th whol work th whole work inklewds th modernist storee line th serch 4 a trew love elements uv gangstr espionage n th serch n what happns evn tho veree labyrinthean also inklewds essays sum abt peopul we know in th known fakshul world introdusing ideas uv ficksyun fakt identitee dew we reelee know them can we n wch them is it a fact n pomes also like th essays hiliting theems that ar in th storee line th charaktrs mooving thru space n time n situaysyuns n thr is a hi degree uv th elements uv randomness wch th strukshur uv th work novel conveys inklewds n is conveying

my first biggest n still biggest influens is gertrude stein who showsd n shows me espeshulee in stanzas in meditaysyuns that words need not onlee 2 represent but ar in themselvs konstrukts wch fold unfold n refiliing fold in2 n out uv each othr ar in fakt puzzuls made uv each othr sew they can b on theyr own not representing bcumming n being what whats dew our grammars cum from our emosyuns n or dew our emosyuns mostlee reelee cum from our binaree based grammar thees unsolvabul qwestyuns prsist n ar oftn endlesslee interesting yes

othr huge erlee influenses allen ginsberg robert duncan denise levrtov bob cobbing diane di prima sew manee infinitlee manee d.a. levy bpNichol martina clinton maxine gadd judith copithorne influences with also sew manee n now 2day peopul othr poets i dew reedings with

sew impressd with adeena karasick kai kellough sheri- d wilson ivan coyote richard van de camp david bateman naomi laufer jill mcginn toshio ushiroguchi-pigott chadwick juriansz ar names uv amayzing poets that jump 2 mind helen posno

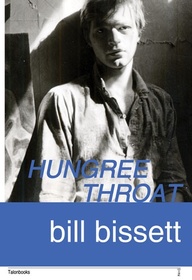

hungree throat my nu book my second novel is mor a novel in meditaysyun 2 charaktrs alredee found each othr trying 2 let each othr farthr n furthr in wun afrayd uv intimasee from his memoreez being 2 chargd n not let go uv how hard that is getting ovr trauma his bad memoree attacks drag him away from whom he loves evn from himself in th present n ths collagist post modernist work tho not as much prhaps as novel inklewds essays pomes seeminglee unrelatid help th reedr n th work 2 reflekt on all th key issews in ths work that cum in2 wun whil reeding hungree throat

thees 2 books ar sew importnat 2 me kathryn n i wud reelee like what yu dew with what ium sending yu 2 focus on hungree throat as it is cumming out in th spring 2013 from talonbooks n th nu book ium working on now is in no way a novel sew thees 2 books ar my 2 novels se far altho th charaktrs ar diffrent peopul thees 2 books cud complement each othr th collagist form works veree well 4 me with th way uv working that can inklewd randomness qwestyuning identitee fact ficksyun 4 me thrs an interesting bredth n spekulaysyun in ths kind uv working th tropes n trajsktoreez longings changes growing n ungrowing lyrik n diffikulteez n treetment uv th konstruktiv urges what we konstrukt what is konstruktid what we can build 2gethr n what we can build n how what we build is building us othr important 2 me writrs hart crane e.e. cummings

latelee ium reeding davisadora by michael ondaatje his comeing thru slaughter is wun uv my all time favorit books

evr p.d.james nu book death comes to pemberley man about town by mark merlis have yu red anne carsons autobiography of red anothr uv my all time most adord books also among th erlier listings touchd on heer erleer in my life that is john rechy city uv night also colm toibin wrote an amayzing book i red coupul yeers ago almost that same titul as john rechy s brilyant city of night colm toibin s book titul is the story of the night camus sartre debeauvoir gide wer huge influenses on me as i was growing in my erlee teens n issac singer shirley ann grau truman capote tenessee williams william inge eugene oneil diane di prima this kind uv bird flies backwards shakespere in school th first sound poetree recording i herd was edith sitwell facade blew me away helpd start me out fr sure as did n dew all thees peopul n sew manee mor

sew hungree throat is a novel in meditaysyun th meditaysyun is abt letting go letting go uv attachment 2 traumatik memoreez n how can yu moov on or 4ward if yu ar klingnig 2 solv or whatevr bad n or haunting memoreez uv th past in wuns life how thees 2 peopul try 2 love each othr thru th dilemma they ar living n what happns

intrspersd thru ths meditayshyun discussyuns conver

saysyuns pledges collapses n regroupings ar pomes song essays its not a book uv doom but it contains sum doom n like all us writrs have n dew talk abt thru th ages how hard 2 love 2 find it n follow thru with it its politiks n sankshuaree part n parts uv th way my throat is hungree 4 breething my throat is hungree 4 eeting my throat is

hungree 4 singing my throat is hungree 4 yu

wrap up qwestyuns n answrs 4 rusty talk hope evreethings great w yu Kathryn

maybe 2 wrap up heer 4 th rusty 4 now aneeway from th beginning i always wantid 2 b writing reelee in approx 7 approaches 2 writing poetree my main wuns being sound n vizual words spred all ovr th page using th space uv th page as whol blank canvas not onlee using a porsyun uv that availabul space as square or rektangul th shape n size uv th copee size n th book size th ekonomeez uv n othr considraysuns have brout th writing in2 lettr size 81/2 x 11 inches drastikalee n finding th wayze thru th availabul transmitting vehikuls n xpanding wuns repertoire 4 inspiraysyun i follow th vois es uv th work at hand or th writing godesses n gods who i sew beleev in guide me 2 write with novel whol passages wer literalee diktatid 2 me sumtimes thrs a lot uv editing as in th pome 4 hart crane in time sumtimes thrs almost no editing th tiny librarians pome in novel went thru seemd ike manee rewrites othr parts uv novel came instantlee iuv nevr xperiensd a writrs blok i cant imagine evn how painful that wud b

i just finishd proof reeding RUSH what fuckan theory a book on theory i wrote n publishd in 72 wch is now being refreshd n reissewd by book thug in toronto my second novel hungree throat will b out in spring 13 n what ium reelee working on now is my nu book mostlee dewing a lot uv lettr texting in it

yu can find a wide range uv my work in you tube n also my web site th offishul bill bissett web site www.billbissett.com

oh thr ar mor thn a few cds out uv my work chek th cv in th website th most recent cd is nothing will hurt with pete dako xtraordinaree musician n arrangr n composr n gary shenkman n ambrose pottie

cest sa i gess thats all 4 now thanks sew much 4 yr interest thees intrviews ar kinduv hard 2 dew sumtimes a prson dusint want 2 bcum 2 self conscious but they reelee help me as well thanks veree much

hungree throat veree recentlee compleetid out spring 2013

hungree throat is a novel in meditaysyun 2 peopul getting 2gethr wun afrayd uv continuing intimasee bcoz uv what has happend 2 him th othr not bewilderd n anxious is eagr 4 nu xperiences with his nu partnr th meditaysyun is partlee abt letting go how hard that is n sumtimez how seminglee eezee th struggul letting go can b owing 2 th obsessing paralyzing n shaping burdns uv our pasts th obstakuls that trauma creates 4 our presents n futurs layrs n layrs ficksyuns n realiteez wch ar peopuls throats ar hungree 4 breething 4 speeking digesting saying singing eeting tasting giving kissing sew much uv th worlds throats ar hungree not onlee 4 evreething also 4 food watr air wun uv th last stages b4 passing uv peopul with parkinsons is whn th throat no longr swallows millyuns uv peopul with sleep apnea sleep with masheens pushing air in2 theyr throats all nite long 2 prevent closure th throat chakra being well is a condishyun uv our life th throat is hungree also 4 acceptans uv what is n what has bin n what is beleevablee possibul thru song sound poetree narrativ n non narrativ analysis meditaysun words n meenings oftn dissolving hungree throat looks at all thees dynamiks 2 share greev celebrate uplift love n moov 4words play with th word growing its parts sylabuls n th mouth n throat shaping each in our times gr ow wo ing wing s

hungree throat by bill bissett, Talonbooks, 2013

Description from the Publisher:

Written in his non-hierarchic, phonetic orthography, bill bissett’s second novel-poem, hungree throat, recounts the relationship of two men – one bold and unafraid, the other burdened by terrible memories and unable to trust. In this uplifting “novel in meditaysyun” about love, in which we witness ten years of a shared life, we are reminded of the overlapping, sometimes conflicting multitude of “hungers” common to us all:

all our throats

r hungree 4 breething being sing

ing eeting digesting speeking

saying food kissing watr love

air ficksyun fakt memoree

th present what is nu all ovr

lapping imbuing change

th throat chakra being well

is a condishyn 4 life

RUSTY TALK WITH SACHIKO MURAKAMI

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Sachiko Murakami: I would write fake diary entries about what me and my friends did after school. I would write these after school alone in my room (often hiding behind a piece of furniture), as I had no friends.

KM: Why did you become a poet?

SM: Um. See: friendless and hiding behind furniture, above. Clearly I was not going to be a professional soccer player.

KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.)

SM:

Step 1: Find something that hooks a thought into a line. Most often I find this happens while walking in an unfamiliar neighbourhood, reading a poem, waking in the middle of the night, etc.

Step 2: Scribble line down (usually on a smudgy receipt, as I am rather bad at keeping notebooks on hand).

Step 3: Bring line to page.

Step 4: Keep going.

Step 5: Revision is an evolutionary process. I wrestle around with the poem for a while, take a break, return, repeat. Then I bring the poem to someone else and watch as they politely break its beautiful legs. Then I begin again.

KM: Rejection or criticism can often stop writers before they start. Do you have any advice on how to deal with rejection?

SM: Stay open! Prepare yourself for the gifts criticism and rejection are going to give you: resilience, yes, but also a curiosity about your work, and better writing. Invite in editors who will politely break your poem's limbs (the key word being politely). Take a workshop. Start a writing group. Get used to criticism, and use criticism. Listen to the questions that are being asked of your poems. Take the serious questions seriously.

Rejection from publishers and literary journals is, for the most part, a numbers game. When I read for literary magazines, there would be a hundred poems submitted for every one page available.

If publication is your goal, then try your best to write publishable material. If writing is your goal, then keep writing.

KM: You used to co-host the Pivot Readings at The Press Club in Toronto. Do you have any advice or tips for new writers about performing their work in front of audience?

SM:

Don't: pre-explain your poems, get drunk beforehand, or go over your allotted time.

Do: Talk to your audience. Look at them. Invite them in to your poems. Go under time. Then thank your hosts and the bar.

KM: From your perspectives as an editor and poet, how would you describe the writer/editor relationship? What should a new writer expect once his or her manuscript is accepted by a publisher?

SM: See above re: breaking of limbs, asking serious questions. As an editor, I think I develop a stronger relationship with the manuscript than with the writer.

In terms of the publishing process, a first-book author can expect to develop the quality of patience. A manuscript passes through many busy hands before it becomes a book.

KM: Can you tell us about your collaborative poetry projects? What got you interested in collaborative poetry? What has the response been?

SM: ProjectRebuild.ca began when I invited some poets into a poem about a Vancouver Special (a type of house in Vancouver). I was interested in seeing how they would interpret my invitation to renovate it as they saw fit. I then had a friend, Starkaður Barkarson, create a website in which any of the poems can be "moved into" and "renovated". There has been a tremendous response to this project—over 200 poems on the site from contributors across the world. The source poem, "Vancouver Special", resides in my second collection, Rebuild.

PowellStreetHenko.ca is an online renga commissioned by the 2012 Powell Street Festival. A renga is a collaborative Japanese form in which each stanza is written by a new person. This renga expands outwards, as you can respond to every stanza in the poem (not just the last one written, as in a traditional renga). Powell Street Festival is a Japanese-Canadian festival held in Vancouver. They asked me to create something like Project Rebuild for them, and this is what I came up with (along with Starkaður). I travelled to Vancouver this summer to launch the project at the festival, and since then the poem has slowly grown as people reflect on change ("henko"), the theme of the poem.

Why do this? I like the idea of putting writing out there that can be taken and messed around with and misinterpreted and reused and repurposed. I like the discomfort it brings. I like prying my writing from my ego's fist. I like conversations.

KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment that you've experienced.

SM: Jacob McArthur Mooney leaving the stage during his reading at Pivot to buy the audience cotton candy from the street vendor passing by on Dundas. No wonder he's the new host.

KM: What are you working on now?

SM: Poems about airports/the struggle to stay present. A novel about fake orphans.

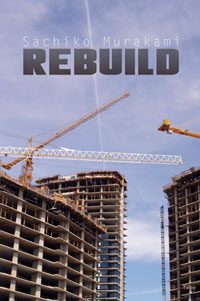

Description from the publisher:

In a city ironically famous for its natural setting, the roving subject’s gaze naturally turns upward, past the condo towers which frame the protected “view corridors” at the heart of Vancouver’s municipally- guaranteed development plan. But look for the city, and one encounters “a kind of standing wave of historical vertigo, where nothing ever stops or grounds one’s feet in free-fall.”

Murakami approaches the urban centre through its inhabitants’ greatest passion: real estate, where the drive to own is coupled with the practice of tearing down and rebuilding. Like Dubai, where the marina looks remarkably like False Creek, Vancouver has become as much a city of cranes and excavation sites as it is of ocean and landscape. Rebuild engraves itself on the absence at the city’s centre, with its vacant civic square and its bulldozed public spaces. The poems crumble in the time it takes to turn the page, words flaking from the line like the rain-damaged stucco of a leaky condominium.

The city’s “native” residential housing style now troubles the eye with its plainness, its flaunting of restraint, its ubiquity. What does it mean to inhabit and yet despise the “Vancouver Special”; to attempt to build poems in its style, when a lyric is supposed to be preciously unique, but similar, in its stanzas or “rooms,” to other lyric poems? What does it mean to wake from a dream in which one buys a presale in a condo development—and is disappointed to have awoken?

In the book’s final section, the poems turn inward, to the legacy left by Murakami’s father, who carried to his death the burden of the displaced and disinherited: the house seized by the government during WWII, having previously seized the land from its native inhabitants—a “mortgage” from which his family has never truly recovered.

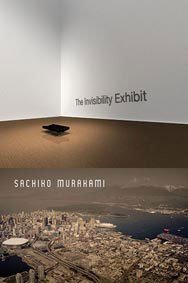

Description from the publisher:

These poems were written in the political and emotional wake of the “Missing Women” of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Although women had been going missing from the neighbourhood since the late 1970s, police efforts were not coordinated into a full-scale investigation until the issue was given widespread public visibility by Lori Culbert, Lindsay Kines and Kim Bolan’s 2001 “Missing Women” series in the Vancouver Sun. This media coverage, combined with the efforts of activists in political and cultural sectors, finally resulted in increased official investigative efforts, which have so far led to the arrest of Robert Pickton, on whose property the remains of twenty-seven of the sixty-eight listed women were found. In December 2007, Pickton was convicted of six counts of second-degree murder in what had become one the highest-profile criminal cases to take place in B.C.’s history; yet this is not the focus of this book.

As the title suggests, the concern of this project is an investigation of the troubled relationship between this specific marginalized neighbourhood, its “invisible” populations both past and present, and the wealthy, healthy city that surrounds it. These poems interrogate the comfortable distance from which the public consumes the sensationalist news story by turning their focus toward the normative audience, the equally invisible public. In the speaker’s examination of this subject, assumptions and delineations of community, identity and ultimately citizenship are called into question. Projects such as Lincoln Clarkes’ controversial Heroines photographic series and subsequent book (Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2002), news stories, and even the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Winter Games circulate intertextually in this manuscript, while Pickton’s trial is intentionally absent.

Irritated by complacency, troubled by determinate narrative and the relationship between struggle and the artistic representation of struggle, Murakami is a poet bewildered by her city’s indifference to the neglect of its inhabitants.

RUSTY TALK WITH RACHEL ZOLF

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Rachel Zolf: I wrote my first poem at a workshop with Di Brandt in Winnipeg in 1990 or thereabouts. Everyone else brought poetry and I brought a failed essay on John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress that stopped short at the moment Christian became a travailer. The travailer part stuck, though. The point not to get somewhere, but to keep slogging.

KM: Why did you become a writer?

RZ: My dad hit me with his foolscap when I was a kid.

KM: What influences your work the most?

RZ: My menstrual cycle.

KM: Could you describe your writing/artistic process?

RZ: I read. I think. I gather things. I make.

KM: In your recent Jacket2 article you mentioned that your work is included in a conceptual writing anthology by women but you don’t consider yourself a part of the contemporary conceptual writing movement. How would you describe your artistic or writing practice or how would you attempt to define it?

RZ: Someone called me a conceptual-materialist, which may be mutually exclusive, or not. Like Lisa Robertson, I am a feminist writer, which encompasses a fair bit, but not everything. The label never fits.

KM: You often work with pre-existing or found texts. What draws you to creating work in this way? And is it ever a problem in terms of copyright and, if so, how do you get around that?

RZ: I am a gleaner (e.g., see Agnès Varda’s film The Gleaners and I), just am. Libel law has scared me more than copyright law so far.

KM: What writers would you recommended to an aspiring writer? Or what writers were influential to you when you first started out?

RZ: I make work from what I read, and it is a different constellation for each book. I don’t want to name names here because the list is always exclusionary. But I do name a lot of names in my books.

KM: What is the funniest moment that you've experienced as a writer or in the literary world?

RZ: The poetry world is unfortunately not that funny. It could do with a dose of levity.

KM: What are you working on now?

RZ: A book of poetry that looks at ongoing colonization in Canada, and a book of essays on philosophy and poetry and the poetics of witness.

Neighbour Procedure, Coach House Books, 2010

Description from Coach House Books:

Rachel Zolf’s powerful follow-up to the Trillium Award-winning Human Resources is a virtuoso polyvocal correspondence with the daily news, ancient scripture and contemporary theory that puts the ongoing conflict in Israel/Palestine firmly in the crosshairs. Plucked from a minefield of competing knowledges, media and public texts, Neighbour Procedure sees Zolf assemble an arsenal of poetic procedures and words borrowed from a cast of unlikely neighbours, including Mark Twain, Dadaist Marcel Janco, blogger-poet Ron Silliman and two women at the gym. The result is a dynamic constellation where humour and horror sit poised at the threshold of ethics and politics.

Photo by Karis Shearer

RUSTY TALK WITH ERÍN MOURE

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative ?

Erín Moure: Biting my toe in the crib and finding out that the waving thing was intimately connected to me. Ouch!

KM: Why did you become a poet?

EM: From the time I read Mother Goose when I was 3 or 4, I thought poet was a valid career choice and no one ever really managed to talk me out of it. It interested me more than my next hotly desired direction, which came later: restaurant owner.

KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.)

EM: Hard to describe. I write most days. I write in pencil in notebooks, I move words, I collect words and bits of text from the Web and elsewhere, I translate and use automatic translators, I generate funny sentences, try to write things down before I forget them. I research a lot too: read philosophy, history, buy plane tickets and go to places: Lisbon, rural Galicia, L'viv in Ukraine. Immerse. Usually by myself so I feel utterly lost. Get really lonely. Revise a lot. Move, cadence, check, read aloud, set aside, read again, move. Read a lot of good poetry while I am working and then cut where mine falls short...no mercy, but lots of fun. I write wherever I am but favourite places are while on my bike (I have to stop to scribble), while on trains, while on the roof deck, while at my desk...but anywhere will do really. I change places so that the work can be read differently. Inhabit language and let it inhabit me. I think. Thinking is a kind of writing too.

KM: How did you get interested in translation? How do you view the role of the translator?

EM: I've told this story before...it's because my mother—Ukrainian born but fiercely always an unhyphenated Canadian, her way of coping with history—always told me there were two languages in Canada, French and English. As a tyke in Calgary, I knew we spoke "English" so I thought French was spoken on the north side of the Bow River. I thought my grandparents spoke French. Then I found out they spoke something that was not French. And I knew there were three languages in Canada.

Then I read Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs. At the back there is a three page bilingual dictionary of Ape-English. So I tried to write in Ape. No English-Ape dictionary though, and no connecting words, so it was impossible. I was maybe 7.

The role of the translator? To transfer joy from one idiom to another. Somehow.

KM: What poets would you recommended to an aspiring writer? Or what poets or writers were influential to you when you first started out?

EM: Read poets in other languages as well as in English: try to read them even if you can't, look intensely at their language. Poets that helped me: Yannis Ritsos, Cesar Vallejo, Federico García Lorca, Clarice Lispector, Nicole Brossard. Early important poets to me: Phyllis Webb, Miriam Waddington, Robin Blaser, Al Purdy, Baudelaire. And Chus Pato, more recently, because, to tell the truth, I am always first starting out.

KM: How do you think the early poet in you would view the later poet? Have you become the writer that you thought you'd be when you first started out in terms of the kind of work you produce, your views, etc.

EM: I am still the early poet! I still love the surprise of exploring in language. I don't know what I've become, to tell the truth. I leave that to other people to define. I am still trying to bite my toe. Though, I guess, early on, I could have never predicted Elisa Sampedrín. Or that I would one day speak Galician.

KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one.

EM: Don't really have one...most things are funny, if you ask me...My favourite would be reading, just reading, always reading, and the feeling of incredible beauty and joy I get in my mouth and throat and chest when I am reading. And going to Vylkove to the Danube Delta with Chus Pato and Manolo Igrexas and swimming in water salt and fresh at the same time.

KM: What are you working on now?

EM: Am working with monologue and chorus texts that could potentially I hope be staged. Poetry but theatre too...delving deeper into that. It's in English and French at once. And is called Kapusta, which is Ukrainian for cabbage.

The Unmemntioable, House of Anansi Press, 2012

Description from House of Anansi

The Unmemntioable joins letters that should not be joined. There is, in this word, an act of force. Of devastation. The unmentionable is love, of course. But in Moure's poems, love is bound to a duty: to comprehend what it was that the immigrants would not speak of. Now they are dead; their children and grandchildren know but an anecdotal pastiche of Ukrainian history. On Saskatoon Mountain in Alberta where they settled, only the chatter of the leaves remains of their presence. What was not spoken is sealed over, unmemntioable. There is no one left to contact in the Old Country. Can the unmemntioable retain its silence, yet be eased into words? Can experience still be spoken?

Photo by Clare Yow

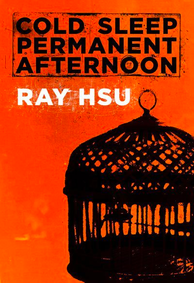

RUSTY TALK WITH RAY HSU

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of being creative or writing creatively?

Ray Hsu: In grade 2 we had to make a book. I wrapped corrugated cardboard in felt for the covers. For the plot I ripped off the storyline for Omega Race:

RH: They seemed to be having so much more fun than novelists, or at least I thought so as an undergrad.

KM: Could you describe your writing process?