RUSTY TALK WITH DANIS GOULET  Danis Goulet Danis GouletPhoto by Clay Stang Award-winning filmmaker DANIS GOULET'S short films have screened at festivals around the world, including Sundance, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Berlin International Film Festival, imagineNATIVE and Aspen Shortsfest. Her film Wakening (2013) had its world premiere before the opening night gala film at the 2013 TIFF, itsinternational premiere at Sundance and went on to win the Outstanding Canadian Short Film Award at the 2014 ReelWorld Film Festival. In 2012, her film Barefoot premiered at TIFF and was also recognized with a Special Mention from the 2013 BerlinInternational Film Festival Generation 14plus international jury. Her work has been broadcast on ARTE, CBC, Air Canada, and Movieola. She is an alumnus of the National Screen Institute’s Drama Prize Program and the TIFF Talent lab. Danis (Cree/Metis) was born in La Ronge, Saskatchewan and now resides in Toronto. Michael Vass When did you first become interested in films, and how did you get into filmmaking? Danis Groulet: I've been interested in film since high school, and I started off working in casting on films like Mean Girls and Love That Boy. After a few years, I began to experience a growing disillusionment with the projects that I was hired for. As a young Cree/Metis woman, I was becoming more and more aware of how pervasive the misrepresentation and under-representation of Aboriginal stories and characters on screen was in all aspects of the screen industry. Shortly after I moved to Toronto from Saskatchewan, I found myself in an audition room for a big US television pilot. The opening scene was an Indian Princess who silently sacrifices herself over a waterfall. That day, the most talented Aboriginal actresses in the city, who I greatly admired, were called in to audition. One by one, they walked into the room, and instead of being given an opportunity to shine, they were literally silenced, reduced to a re-enactment of a noble sacrifice. I still remember the powerful image of their faces in silence. As the casting session continued, I sunk deep into my chair in shame at the thought that I was the person behind the table, supposedly representing part of the team putting this out into the world. Spurred by that experience, the penny dropped for me: we had to make our own films. I wish I could say that directing had always been a calling. But it was more of a sense of feeling implicated to try because there were so few Indigenous filmmakers out there around that time. In 2003, I made my first short film spin and absolutely loved everything about the process. I also attended my first imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival. By the next year, I was running the festival and was immersed in the Indigenous film community. MV: Is there a filmmaker or writer (or more than one) that has been a particularly significant influence on your work? DG: I think for Barefoot, I was profoundly influenced by the films of Andrea Arnold. I still remember completely freaking out after seeing her short film Wasp at Sundance in 2005. Her films are brave and uncompromising, led by female characters who also seem to be enigmas onto themselves. I loved Red Road as well. MV: What is your favourite part of the filmmaking process? DG: The adrenaline of shooting. I love the choreography of all of the elements and the immediacy of it. It demands that you completely face every moment with your eyes as open as possible. The closest experience that comes to it for me is being in labour! MV: Where did the idea for Barefoot come from? DG: I saw my little cousin's Facebook update that said: "At 21 weeks, your baby is about the size of a carrot." This is how I found out that she was pregnant, and she was in her last year of high school. The film is set in northern Saskatchewan where I was born and spent my childhood. My cousin's update got me thinking about how normal it is for many Aboriginal women to have kids at a younger age. There are very few options for girls growing up on the reserve and they face incredible challenges. It is logical to me that motherhood would be seen as a great option for a young woman. It was important for me to situate the film from the perspective of a girl who wants a baby more than anything else and sees this as her future, and outside of the values of a more mainstream middle class perspective that might judge teen pregnancy. MV: In Barefoot, and in other films, you have used non-professional actors—can you talk about why? How is the process of casting, rehearsing, and directing non-professionals different from working with experienced actors? DG: I started in casting, so have always had an enormous respect for actors and the importance of performance to any film. However, at some point, I decided that I wanted to move away from all of the filmmaking "shoulds" to just experiment with the process and see what might happen. Working with professional actors was a golden rule for me, so deciding to work with non-professional actors was a way to break one of my own golden rules to see what would happen—and it was incredibly liberating. With non-professional actors, you still ultimately need to find performers, and I can honestly say that all of the non-professional actors in my films (including some members of my own family) are fantastic performers. In Barefoot, we also built a huge amount of rehearsal time into the schedule. We did five days of rehearsal and five days of shooting—which is a huge rehearsal ratio for film. We chose ten teens out of 200 from northern Saskatchewan to work with us for five days, and we cast the leads on the 4th day of rehearsal. I worked with a couple of experts in Forum Theatre, Warren Linds from Concordia and my mom Linda Goulet who works at First Nations University. They used theatre methods to work with the kids for the first three days, and it was incredibly powerful. I ran quite a lot of improve—we didn't really rehearse any scenes from the script but focused more on opening up and becoming comfortable with the process and with one another. We also had an Elder present for the whole rehearsal, Ida Tremblay who plays the grandmother role in the film. The kids went through a lot over those five days, and they all had a lot going on at the time. Her presence was important to the film, it made the kids feel safe, and they could talk to her at anytime if they needed to. MV: What are you working on now? DG: I'm writing my first feature, which is set in a dystopian future. I'm hoping to get my next draft off before Christmas. I'm also planning to shoot another short film set back in my hometown (same as Barefoot), but this time in the 80s at the rollerskating rink. It's based on my summer grade five crush on the skinny guy from the far reserve. I'm not sure how much hairspray will be used in the making of the film, but I'm pretty sure that it will be a lot. WATCH DANIS GOULET'S FILM BAREFOOT |

| About Barefoot In a tight-knit Cree community in northern Saskatchewan, sixteen-year-old Alyssa’s plans to become a mom begin to unravel. To learn more about this film visit the Barefoot website. |

Michael Vass is filmmaker and writer and a regular contributor to The Rusty Toque.

Chelsea McMullan

Chelsea McMullan RUSTY TALK WITH CHELSEA MCMULLAN

Sarah Galea-Davis: How did you first get into filmmaking?

Chelsea McMullan: I don't think I've found a way to say this yet that doesn't set off my precocious detector, but I wanted to make films from a young age. There's no great story or anything, just a progression from my parents' camcorder to studying film at York University in Toronto straight out of high school. Part of me wishes I'd came to film later because I think it would have been great to study something like philosophy or psychology first. At the same time though, I still work with the same people I met in my undergrad.

SGD: Was there a writer or filmmaker that had a big impact on you?

CM: On a personal level Jennifer Baichwal has been hugely influential. I interned with her and her husband Nick de Pencier right out of film school and despite being a thoroughly wretched production coordinator/researcher, they've both been so patient and generous with me over the years. I was occupying a corner of their office rent-free for like four years. I used to sleep on their couch, in the editing suite, when I was up late writing a grant. Also they are fucking awesome filmmakers, and over the years I've been able to watch their process and learn from them, while deeply engaging with pragmatic, ethical, and philosophical issues around the films I'm making. My absolute favourite filmmaker is Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Hands down, end of discussion, to a very obsessive extent. A few years back in Berlin, I bought a book, which is comprised of a still image of every frame in Berlin Alexander Platz. It's like 50 lbs, and my baggage was obscenely overweight, but it was totally worth it. I would say it's one of my most cherished possessions. Actually, the mayor of the town I grew up in was his cousin. I asked him about it once, and he told me a wild story about spending time with Rainer. I think it was supposed to be a cautionary tale.

SGD: What is your favourite part of the filmmaking process?

CM: I find that I'm sort of anxiety ridden through the whole process. Though if I have to choose my favorite part, it is probably watching rushes. There is still so much promise and nothing has gone wrong yet, but you’re past the soul-destroying production hump. It's a nice purgatorial state before you have to pull your baby apart and sacrifice it to keep the gods happy.

SGD: What is the best filmmaking advice you've received?

CM: Once something really bad had happened to the main subject of one of my films. His wife had a horrible brain aneurism and was in the hospital. I was young, so I thought the film was over and was ready to throw in the towel. I phoned Jennifer and told her about the situation, and she was like "Chelsea, this is your job. This is what being a documentary filmmaker is." I've never forgotten that. The times it feels most difficult and awkward to shoot are the times when usually it is most important because those are the moments of people's lives that we don't really share enough. Also more often than not people want their tragedies documented. They want to feel like people are experiencing with them, that there's value in their loss.

SGD: Your work spans the genres of documentary and experimental filmmaking. Do you approach the writing/creation process differently when it comes to your non-fiction work?

CM: I never set out to make documentary, fiction, or experimental films. A subject just crosses my path, and I follow it down the rabbit hole. I also feel like my work usually sits in some space of hybridity. I've never sought out a subject for a film, it always comes to me, and then I just try to tell the story in the best way I know how. The genre, the length, the style for me are all dictated by the subject matter.

SGD: Tell us about your current documentary that is being released in November?

CM: The NFB hired an actual writer to explain it in a concise and inviting fashion. Know that it is a passion project that Rae and I have been working on for the past four years or so together. Rae is a good friend and this was an important project for me.

SYNOPSIS: MY PRAIRIE HOME

In Chelsea McMullan’s documentary-musical, My Prairie Home, indie singer Rae Spoon takes us on a playful, meditative, and at times melancholic journey. Set against majestic images of the infinite expanses of the Canadian prairies, Spoon sweetly croons us through their queer and musical coming of age. Interviews, performances, and music sequences reveal Spoon’s inspiring process of building a life of their own, as a trans person and as a musician.

TRAILER:

Bob Kerr

Bob KerrPhoto by Craig Brown

RUSTY TALK WITH BOB KERR

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Bob Kerr: As a fan of Letterman, I would write my own Top Ten Lists and read them to my fellow kids at the back of the bus. I also wrote stories that were a direct inspiration of movies I was into. I wrote a story that was about a baseball team that was trapped within a (Jurassic Park-type) jungle and the star pitcher was bitten by a "gypsy hamster" that turned him into a (Pet Sematary 2-style) zombie. Really dumb.

KM: When did you first start writing for film/TV and how did you get into it?

BK: I was a member of a comedy troupe called The Sketchersons, and we did a weekly show called Sunday Night Live which heavily borrowed from the format of Saturday Night Live. I had done the Weekend Update part of the show for a large part of the time. Producers who saw the show asked me to submit things. My first writing gig was a for a late-night talk show pilot that didn't go anywhere and that was followed by my first trial run at This Hour Has 22 Minutes.

KM: Was there a writer or filmmaker that had a big impact on you?

BK: It was mainly performers, actually. David Letterman and Conan O'Brien were big influences. They do what they want to do. And a lot of it's really weird, and I like weird things.

KM: How does the writing room work for This Hour Has 22 Minutes?

BK: Early in the week, we pitch sketches and spend the whole day and night writing them. After the table read, sketches are picked and then the following days are focused more on copy jokes (a.k.a. news jokes...y'know, the set-up-punch stuff) and things called ledes, which is writing jokes around actual news footage. We sometimes pair up on sketches, but there's a lot of independent writing. My favourite days are writing copy jokes because we have table reads of those jokes amongst the writers and we have a couple laughs. Sometimes even more.

KM: For someone looking to get into TV or comedy writing, a writing room—especially a comedy room—can seem intimidating. Do you have any advice for how to get over feeling like an idiot if your joke fails or no one likes your ideas in the room?

BK: Trust me, I know what it's like to feel like an idiot. I've had plenty of stuff bomb in the room. An important thing to remember is that you're in good company; everybody bombs. Bombing is a very key part of the writing process. Because you learn from it. Mainly what works and what doesn't. So ultimately, don't dwell on feeling like an idiot. Because you will miss the bomb lesson. It's not about you! Get over yourself! Move on! (I feel like I'm talking to myself now.)

KM: What is your writing process like for your other projects—other collaborations or solo projects?

BK: Typical; go to coffee shop, order an Americano and stare at my computer screen. Collaborations can be fun if you're doing it with the right person. Someone that you feel comfortable bouncing ideas with.

KM: What is the biggest difference between writing for film and writing for TV?

BK: You spend way more time with a film script than a TV script. There's pros and cons to both. With TV, you don't have all the time in the world to make "the perfect script", so there's not much time for rewrites. You are also forced to write a lot and quickly and that kind of pressure is good. I think you get better stuff from that. Plus, there's a whole writing room that will punch up your ho-hum material. Again, it's not about you.

KM: When getting notes from producers/story editors/show runners—what do you do when you get a note that you don't like or don't agree with on your script?

BK: Well, there's two ways to go about it. You either don't make the change and pray they don't notice (which they usually do), or you talk it out with said note-giver. That being said, pick your battles. One thing I've learned in TV is that I can't be too precious with anything I write. With 22, there's not a lot of time, because I'm most likely onto something else. Plus, it's hard to feel precious about something I've worked on for a couple of hours the night before as opposed to something I've been working on for weeks or months.

KM: Do you have any advice for someone aspiring to write for television? What is the best way to break in?

BK: I don't know what the best way is. I only know my way. I was tenacious and I wrote a lot of stuff. I was out there performing with a great troupe every week on top of doing stand-up and I was getting myself seen. It's a lot of work to get a job. There's also the standard advice: Write spec scripts, get an agent, write more spec scripts.

KM: What are you working on now?

BK: I'm going to be returning to Halifax for the 20th season of This Hour Has 22 Minutes. I'm currently working on a spec pilot as well. I'm also trying to think of a funny tweet.

| Short Film: The Funeral |

Michael V. Smith

Michael V. SmithPhoto by David Ellingsen

In recent years, Smith won Vancouver's Community Hero of the Year Award and the inaugural Dayne Ogilvie Award for Emerging Gay Writers. He's also won a Western Magazine Award for Fiction, scooped two short film prize categories at Toronto's Inside Out festival, and was nominated for the Journey Prize.

His videos have played around the world, in cities such as Milan, Dublin, Turin, London, New York, Toronto, Paris, Geneva, Berlin, Glasgow, Lisbon, Beirut, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Buenos Aires, SF, LA and Bombay. Smith is an MFA grad from UBC’s Creative Writing program.

Vancouver Magazine has considered him one of its city's 25 most influential gay citizens whereas Loop Magazine named him one of Vancouver’s Most Dangerous People...

His first book of poetry is What You Can’t Have (Signature Editions, 2006), short-listed for the ReLit Prize. In 2008, he published a hybrid book of concrete poems/photographs, Body of Text (BookThug), created with David Ellingsen.

RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL V. SMITH

Kathryn Mockler: What keeps you going as a writer?

Michael V. Smith: I’ve always loved a puzzle. My novels have felt like long complicated puzzles that I tried to figure out. Really, every book is a mystery novel, right? You read to the end to find out the whodunnit, in whatever shape that takes. How is this book going to end? Even, how is the poem going to end? How does it work? So writing is the best way to enjoy making puzzles (long ones like novels, short ones like a poem) and still get paid.

Okay, I use teaching to get paid.

What keeps me going is a fine alchemy of things. There are many pleasures in creating: simple ego-stroking, the thrill of feeling like I’m discovering something, a satisfaction in accomplishment, being generous with myself, the feeling that I’m creating a conversation with someone about a collection of ideas (or characters) I’m very fond of, and the pleasure that comes from being engaged with the world. I’ve never thought of writing as a solitary act. I don’t know where that idea comes from. Writing is a very long one-sided conversation, but I’m always aware that eventually an audience will hear it, and listen, and join in.

Kathryn Mockler: What is the revision process like for you?

Michael V. Smith: With novels, after I have a first draft, I take out all the parts of the flab that aren’t plot. Just cut it all away. If there are bits of information I particularly like, or can’t do without, then I find somewhere to slip that back in. Usually, that first draft, cleaned up, is a solid skeleton.

Then I do drafts that look at fixing specific things: I go through the whole manuscript, for example, and look at tying the events more closely together, so that one event is the cause of what comes next, or I do an edit to ‘psychologize’ the characters, meaning I add in some of the unwritten emotional life of the character, or flush out a bit of background, to fill out our sense of character. It’s a great way to edit for me, because it gives me focus on a particular skill.

I always do other work at the same time, of course. One type of change triggers five others. But if I’m just approaching the novel as a whole, it’s overwhelming, and hard to see it clearly, so I love going in there with a tool in hand and digging around, which makes the whole process more manageable.

Kathryn Mockler: How did you deal with rejection when you first started out?

Michael V. Smith: Rejection is all part of the business, so if you aren’t rejected, you aren’t in the business. I take rejections as a good sign—I’m being a writer.

Kathryn Mockler: What are you working on now?

Michael V. Smith: I'm working on two projects: a series of tribute videos to friends and family who are ill, and a collection of essays titled Men.

Progress, Cormorant Books, 2011

Description

Since her fiancé’s death at eighteen, Helen Massey has spent her life avoiding it. Change comes when her town is only months away from being thirty feet under water. A government agency, The Power Authority, is relocating the entirety of her hometown to make way for a power dam project. What can’t be moved will be torn down. Even the cemetery is to be dug up and reinterred nearby.

While visiting her lover’s grave, Helen witnesses a man fall to his death on the power dam worksite. “He fell like a sack, straight down, with one arm waving in circles. He fell past the other workman strapped into a harness who must have been surprised to see him pass. Mocking the air. It seemed he fell without a sound.”

That same day, her brother returns unannounced after a fifteen-year absence. Robert Massey was a runaway. The construction made his homecoming a “now or never” decision, he tells his sister. “I didn’t want to have to come back in a boat to see the family home.”

When Robert discovers his parents kept the reasons for his departure a secret—too little has changed—he confesses, hoping his sister might bury the past. So begins their transformations. The siblings must negotiate their shared history, and their differences, if they are to find themselves a future.

In his essay, "A Memoir of Progress," Matthew Rader offers a brief memoir about his experiences with Michael V. Smith's latest novel Progress. This essay is published by AngelHousePress.

Read an excerpt of Cumberland.

For more information about Michael V. Smith go to his website.

Ivan E. Coyote

Ivan E. CoyotePhoto by Eric Nielson

RUSTY TALK WITH IVAN COYOTE

Sara Jane Strickland: What is your first memory of being creative?

Ivan Coyote: I am not sure if I have a memory of this or not, or if I feel like I remember it because there is an old old photo of me doing this, but I have a memory of setting up pots and pans like a drum kit on the front deck of my parent's first house and playing the drums on them. I would have been about two or three.

SJS: How would you describe your writing process?

IC: Deadline driven. I set or get goals and dates, and I try to follow them. I have thousand word days. I make myself write a thousand words, good or bad, not perfect words, just out there. Out of my head and onto the page. Also I make lists of scenes or chapters or stories or ideas and then I just try to write them and cross them off.

SJS: What are you working on right now?

IC: A novel and a survival guide for tomboys. Also two live shows, both collaborations with musicians.

SJS: What is the revision process like for you?

IC: I just grin and bear it.

SJS: What influences your writing the most?

IC: Life. Other books. Other writers. The sky. The weather. How much I have been to the gym lately. Music. Dance. Painting. Movies. Things I overhear on the bus. Kids I meet. People I meet. Loved ones. Loved ones dying. New ones being born. Life.

SJS: How did you deal with rejection when you first started out?

IC: The first book I was a part of writing, we got asked by the publisher for a manuscript, so I have an unusual story. I didn't have to deal with a lot of rejection right out of the gate.

SJS: What keeps you going as a writer or why do you write?

IC: I write because I love it more than anything else in my life. I write because I don't know or remember how to be anything else anymore. I write to pay the bills. I write to change the world. I write because I have a deadline. I write because not writing is no longer an option for me. I write because it is the only way to navigate this life, for me.

SJS: What is the best thing about being a writer and the worst thing?

IC: The best thing? Working alone from home with no pants on. The worst thing? Working alone from home with no pants on.

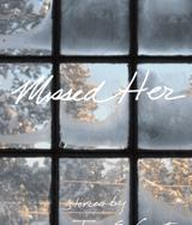

Missed Her, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010

Description from Arsenal Pulp Press:

Ivan E. Coyote is a master storyteller and performer; their beautiful, funny stories about growing up queer in the Canadian north and living out loud on Canada's west coast have attracted big audiences, whether gay, straight, trans, or otherwise. In their passionate and humorous new collection, Ivan takes readers on an intimate journey, both literal and figurative, through the experiences of their life: from their year spent in eastern Canada, to their return to the west coast, to travels in between. Whether discussing the politics of being butch with a pet lapdog, befriending an effeminate young man at a gay camp, or revisiting a forty-year-old heartbreak around her grandmother's kitchen table, Ivan traverses love, gender, and identity with a wistful, perceptive eye and a warmth that's as embracing and powerful as Ivan themself.

Reviews

What happens when a woman with "dykey clothes" confronts a man with a bushy beard about the lesbian book he's reading? Is life easier for a butch or a lipstick lesbian? Is it better to be queer in Whitehorse, where you're subjected to direct questions, or in Vancouver, where PC politeness masks embarrassed confusion? Missed Her, a collection by Vancouver writer and performer Ivan E. Coyote, conveys these lifestyle collisions with thoughtful humour ... Thematically, Coyote's writing has grown in complexity and depth.

--Rabble.ca

These vignettes read as though they've been freshly torn from a wanderer's notebook, where they were immediately jotted down so as not to lose the vibrancy of the experience. The result is refreshing and tearfully real--Coyote has a gift for blending the tragic and comic in a way that renders a reader gobsmacked ...The writing in Missed Her is direct yet lyrical, poetic yet unadorned, reaching simultaneously for the heart and the gut with brevity and power.

--Quill & Quire (STARRED REVIEW)

Read More

Photo by June Pak

RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL VASS

Kathryn Mockler: How did you first get into filmmaking?

Michael Vass: I’m not completely sure. As a child I think I was drawn to performing—for instance, I loved stand up comedy at what now seems a weirdly young age (I couldn’t possibly have understood most of the jokes)—but I don’t think I was ever completely comfortable performing myself, at least not after a certain age. So I started writing stories then making videos, probably initially as a way of performing out of sight. When I was 11 or so, I started making little home movies with my friends and my sister. We’d make parody sequels for movies that were popular at the time. I think we made Home Alone 2 and Die Hard 3 (which we called Die the Hardest) before either sequel really existed. Since then I’ve just kept making things. As a teenager my interest in film intensified, then I went to film school where I was exposed to all kinds of films that fascinated and excited me.

KM: Was there a writer or filmmaker that had a big impact on you?

MV: There are too many too name, and it tends to shift somewhat depending on what I’m working on. For my most recent project, Vancouver #1-13 (Notes for a report…), I was influenced mostly by filmmakers working in the somewhat amorphous genre that’s sometimes called the essay film, which has long fascinated me. The term itself isn’t that important, it’s just a way of grouping together a kind of film that’s always been around, which combines elements of fiction and documentary, and which tends to have a significant writing component—usually in the form of a first person voice-over. It’s generally a more self-reflexive and personal way of using various cinematic techniques, and it often addresses somewhat political themes, directly or indirectly. Film/video-makers like Chris Marker, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Jean-Luc Godard, Harun Farocki, and John Smith had a particularly strong impact on me as I was working on the film, as did the writers Robert Musil, W.G. Sebald, Thomas Bernhard, and Roberto Bolano.

KM: Can you describe your current film project that's screening in Philadelphia?

MV: It’s called Vancouver #1-13 (Notes for a report…) and, as I mentioned, it’s a kind of essay film, which mixes documentary and fiction to examine security and protest in the society of the spectacle. It uses documentary footage from the 2010 Vancouver Olympics and the G20 debacle in Toronto, and adds a voice-over by a fictional intelligence agent analyzing the footage. It is currently screening as an installation in the group exhibition “First Among Equals” at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Philadelphia (April 11-22). My participation in show came about because of my involvement with the Philadelphia-based gallery Marginal Utility and the Machete Group which jointly puts out the publication MACHETE, for which I’ve been writing about film for the past couple years.

KM: What is the best thing about being a filmmaker and the worst thing?

MV: The best thing about being an artist of any kind is that it lets you structure your life around engaging with the world and your experiences and interests on your own terms, or at least on terms of your choosing—creatively, critically, reflectively…however you want. The worst thing is that this kind of activity rarely pays the bills, so usually you have to find some other way of making a living. Sometimes this can be something tangentially related to your activities as an artist (like teaching), or sometimes it is something completely unrelated, but either way it tends to eat up a lot of time and energy you’d rather be spending working on your own projects. This financial downside is exponentially worse as a filmmaker because filmmaking is so expense, logistically complicated, and time consuming, so if you want to make your own films, it can obviously be quite difficult. But artists shouldn’t whine too much about jobs and money – almost everyone hates there job and would rather not be doing it, at least we have something we want to be doing.

KM: Your funniest filmmaking moment.

MV: I directed a film at the Canadian Film Centre in 2006 called Skinheads. The film is a dark comedy and isn’t exactly about actual skinheads in any real way, it just appropriates some of the iconography of skinhead culture for other purposes. We put a trailer on YouTube to promote the film at festivals, etc. However, we didn’t anticipate that there are a lot of actual skinheads all over the world searching online for skinhead related stuff. The trailer has received a ton of views in the past year, along with some affronted comments by Neo-Nazi types. Somehow the trailer must have gone viral in some minor way recently on skinhead sites or something and has generated some negative attention. Maybe that’s not ha-ha funny, but I find it kind of amusing—as long is there is an ocean between the offended skinheads and me.

As a director resident at the Canadian Film Centre, Shum developed her first feature-length film Double Happiness, which premiered at the 1994 Toronto International Film Festival, receiving the Special Jury Citation for Best Canadian Feature Film and tying in third place with Kieslowski for the Toronto Metro Media Prize. Double Happinessgarnered Canada’s highest film honours, winning Genie Awards for Best Actress (Sandra Oh) and Best Editing (Alison Grace) with additional nominations for Best Picture, Best Direction, Best Screenplay and Best Cinematography. It also won 1995 Berlin Film Festival prize for Best First Feature, as well the Audience Award at the Torino Film Festival in 1994. After it’s US premiere at Sundance, it was released theatrically in the U.S. by Fine Line Features in 1995. Her second feature Drive, She Said premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in 1997. The film was invited to the competition section of the Turin Delle Donne Film Festival in 1998. Shum’s third feature film,Long Life, Happiness and Prosperity premiered at the 2002 Toronto Film Festival and played to sold out audiences at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival. It won a Special Citation for Best Screenplay at the Vancouver Film Festival. It will be released theatrically in Canada by Odeon Films and in the U.S. by Film Movement.

Shum has written and directed several short films, including Picture Perfect, which was nominated for Best Short Drama at the 1989 Yorkton Film Festival, Shortchanged, Love In, Hunger, Thirsty and Me, Momand Mona which won Special Jury Citation for Best Canadian Short at the 1993 Toronto Film Festival. Her 2011 web short, Hip Hop Mom has garnered thousands of hits and can be viewed for free at www.minashum.com.

Shum directed the television movie, Mob Princess for Brightlight Pictures/W Network. Her episodic directing work includes: About A Girl, Noah’s Arc, Exes and Oh’s, Bliss, TheShield Stories and Da Vinci’s Inquest for which she was nominated for a Director’s Guild Award. Her episodic work has been seen on CTV, Global, Nickelodeon, CBC, N, Logo/MTV, Showcase and Lifetime.

She is currently writing and developing her next feature film, Two of Me, with Brightlight Pictures, as well as writing and developing other feature projects including, The Lotus (co-written with Dennis Foon).

RUSTY TALK WITH MINA SHUM

Kathryn Mockler: How did you first get into filmmaking?

Mina Shum: When I was 7, I got down on one knee, spread my arms wide like Al Jolson and declared "I want to be in show business." At 12, I started my first journal and wrote everything I thought, felt, and heard down. I would copy things I'd overheard on the bus ride home, word for word to examine the patter of speech and the subtext of a banal conversation between two ladies about a cupcake recipe. In grade 9, I was failing my knitting class and transferred to Drama and that was the beginning of my official training as a filmmaker. I went to theatre school at UBC, got a film diploma after my BA, and continue to study and practice the craft.

KM: Where do you get your ideas from or what or who inspires you? MS: I am a voracious consumer of ideas, movies, art, theatre, music, dance, fiction and non-fiction. I read interviews with people I've never heard of. And I listen to both friends and strangers speak. I live entirely, throw myself into situations, get my heart broken, soar with infatuations. And somehow all that gets funneled through my guiding intention, which is to reflect and reveal how we can be happier. How to live more authentically, how to make the most out of this one life.

So, how does this hodge-podge of thoughts gets distilled through my next feature? Two of Me is an irreverent romantic comedy about an overworked 35 year old super woman (two kids, live-in-mother-in-law, husband, high pressure job, trying to get promotion) and she's granted a wish for "two of me" except the other "me" is ten years younger when she was a no-good indie rock musician. It's a film about who you once were and who you've become and the disconnect that often occurs when we're busy living life! At its heart, it's about surppressing our true nature (which I think all my films are about).

KM: What is the writing process like for you?

MS: I get hooked on an idea, a question and I write.It starts in the title which I believe should say what's the essential theme/idea behind the movie; it starts with a good title. Then I write the three-sentence pitch. If I can do that, I move on to a proposal that is half director's vision and writer's beats. But after that I work on my treatment, which is beating out the film pretty well. And at this point it's the writer's hat I'm wearing. The writer has to deliver on the promise to the director. Being both writer/director, I have to know when to wear which hat. The director in me is a heavy taskmaster and will continue to make me (the writer) work the script until it sings and I take it over as a director. And then when I direct the film, I will continue rewriting bits even in the sound mix of the film.

KM: How do you approach revision?

MS: I rewrite until you are watching the movie in a theatre. When I say that, I mean in marketing, in my interviews and in my q and a. I assume that all the notes I get, is just gonna make the film better. I do reject notes. But if the same note is coming over and over, I take notice.

KM: Writers/filmmakers often have to face a great deal of rejection, especially when they first start out. Do you have any advice for aspiring filmmakers on coping with this?

MS: Nothing is ever lost when you practice. I like to think of all of life as a practice. Malcom Gladwell says it takes 10,000 hours to get really good at something. Clock your 10,000 hours. Keep working on it. I write and direct everyday even if it's just in my mind, toying with concepts or even a note to a friend.

Trust the path.

KM: What is the best thing about being a filmmaker and/or writer and the worst thing?

MS: Best thing about being a filmmaker, making a film.

Worst thing: waiting for the funding to make a film. But even as I write that, I know that I have to "practice" making that part fun, part of the process.

At best it takes fours years to go from thought to you seeing it on the big screen. That's four years of living, breathing and waiting. Or should I say "practicing"?

Photo by Matt Lyons

Check out Mina Shum's latest 4-minute short Hip Hop Mom.

Synopsis

When two alpha moms fight over a parking spot, they reveal their secret identities, and it's a hip hop battle royale!

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed