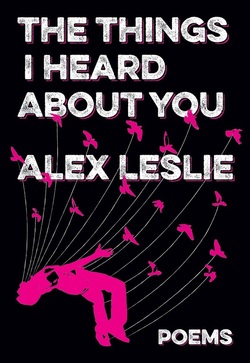

RUSTY TALK WITH ALEX LESLIE Photo by Lorraine Weir Photo by Lorraine Weir ALEX LESLIE has published a collection of prose poems, The things I heard about you (Nightwood, 2014), a collection of stories, People Who Disappear (Freehand, 2012), shortlisted for a 2013 Lambda Award and a 2013 Relit Award, and a chapbook of microfictions, 20 Objects for the New World (Nomados, 2011). Alex's writing has won a Gold National Magazine Award for personal journalism and a CBC Literary Award for fiction and was shortlisted for the 2014 Robert Kroetsch Award for innovative poetry. Their poetry will be included in Best Canadian Poetry In English 2014 (Tightrope Books). Recent projects include editing the Queer issue of Poetry Is Dead magazine, which brought together different approaches to Queer poetics from across Canada. Website: alexleslie.wordpress.com. Sara Jane Strickland: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Alex Leslie: In kindergarten, there was an assignment to write a riddle. For whatever reason, this assignment became a kind of obsession for me. I remember writing more than the required number of riddles and then having to choose between the riddles. This was a Sophie’s Choice situation for five-year-old me. One riddle I wrote was “What travels all over the world but is always in the same place under foot?” I was very adamant that underfoot was different than under foot and I remember the arguments from my classmates that I was “cheating” and that this was “unfair.” It stays under your foot. The answer was the sole of your shoe. Apparently, the sound/word under foot could not be used in this tricky, ungrammatical way and I was a cheater. I have memories of hiding under a table. One other riddle involved a gun; I don’t remember the riddle, just that it involved a gun and that this was “disturbing” and that this riddle was quickly disqualified by the teacher. No weapons; no messing with portmanteaus. After this, I began to write stories about our neighbours as caricatures, for example “Liora the Witch.” I had no mercy. I also was convinced that I was the most hilarious person on the planet, which helped. Then I wrote longer and longer things, all fiction. I was always working on writing projects through elementary and high school. But thinking back, the riddles were the beginning. I was going to write the best riddle. I just wanted to write a really hard riddle so that I could have the opportunity to tell everybody about my clever word game. I do not recommend this social strategy to today’s kindergarten students. The world needs you to survive. SJS: What is your writing process like? (How often do you write? Where? When? Etc.) AL: My life is currently deeply split between graduate school and my writing practice. My degree is not in an artistic or literary field, so there is some measure of separation there, which is good. My writing process is that I write things in series, to sustain momentum and motivation; writing things in series is very helpful when there are other forces in your life. It gives you a thread to hold onto through everything else. I carry around a notebook that I write helpful ideas and phrases in. I also tend to write myself emails on my iPhone, so I receive lots of emails about scenes and phrases from the Gmail sender “me.” Me sends me lots of cryptic random stuff. If “me” were not me I would be concerned. When a piece reaches a certain stage, I print it out and carry around a copy that I mark up with notes. I only work well when my process is very organic and disorganized and I have succumbed to the fact that this is just how it goes and eventually I get somewhere without really noticing. I don’t have a specific time of day when I write; late at night works and in the summer I often wrote in the morning, when I didn’t have classes (but who are these schedule-less writers who can write all the time at their ideal time?). I do have a workspace in my home, which helps. I would like to add that other writers are part of my process. I’ve been workshopping with poet Adrienne Gruber for several years. Her next book is out with BookThug and her chapbook Intertidal Zones is just out with Jack Pine. SJS: How do you approach revision? AL: Revision is my favourite part. I print it all out. I carry it around and cross things out. I write things in. I prune. I fiddle. It is like having a bonsai tree in your backpack that only you can see. I obsess. I remember reading an interview with Michael Ondaatje (whose early experimental fiction such as Coming Through Slaughter is very important to me) that writing a novel is like building an imaginary city in your backyard. Yes, that’s what it’s like. Revision is great but there is a sense of loss when the book is done. Then you go on to the next thing. SJS: When you started writing your latest book, The things I heard about you, did you write each poem with the intention of making it into a collection or did it happen more arbitrarily? AL: This project began because of the line “I know how small a poem can be” by John Thompson from Stilt Jack. At that point, maybe three or four years ago, I was struggling with the short fiction form—the need to “conclude” and have an “arc” and what I can see now as the usual post-first-book anxiety about the form that created you—and the phrase “I know how small a story can be” came to mind. It took me a while to arrive at how to begin this process but I started to write vignettes or prose poems around certain intense experiences/events/scenes; these pieces were based on photographs. I then did a “blackout” process whereby I wrote increasingly “smaller” versions of these pieces of text. So the method always was what connected the pieces in my mind. No, I didn’t intend to make a collection of these pieces. It was a project that interested me on a technical level as a writer of stories/poems/cross-genre things. I wrote these pieces until the process lost its purpose or interest for me. The technical process of literally breaking down texts helped me to find language in my descriptions that I hadn’t been aware of, to become more aware of my own rhythms of writing, and to uncover connections in the pieces that I hadn’t seen before. This process taught me a lot about myself as a writer. SJS: The poems seem to deal with a monumental sense of loss juxtaposed with a sense of freedom and hope. How did these themes, or others, influence the stylistic decisions for the book? AL: Thank you for that reading. I didn’t consciously choose those themes for the book. I think that many of the pieces explore space in a layered way, in particular the coast and the structure allowed me to reflect different aspects of environments. I would also say that relationship is a theme in the book; there are several pieces about taking apart another person, or considering the different parts of them. I do think that the pieces that deal with loss, in particular grief, move to a place of release (the word I would swap in for “hope”) partly through the structure, because the structure demands that the original text shrinks, has the heavier parts lessened, discovers the more concentrated parts of itself. I’m glad that produced a sense of freedom or hope in your reading. SJS: How did you approach the poems as a collection? Did you mean for them to have a narrative or was it purely coincidental? AL: In the end, I ordered the pieces for pacing, both in terms of more intense pieces being spaced out. I am curious what narrative you found in the pieces overall? Do you mean a story narrative? Or a narrative created by the evolving form of the pieces? SJS: The narrative I am referring to is definitely emphasized by the evolving form of each piece (which is actually quite beautiful, I might add). I think perhaps the kind of narrative I am talking about is more of an "emotional narrative" that runs through the book. In my interpretation, it is this back and forth between things, or people, that are lost and found. Where do these ideas come from? What inspired you to write these poems? AL: I like that idea that it is a movement between things that are "lost and found," because I like to read the poems as fluid components rather than being something static, like different steps on a staircase. Several of the poems that centre around loss do speak out of losses in my life over the past five years. In particular, the piece in the collection "Knockin On Heaven's Door" is about the intense, initial period of grief and the (I think common) coping strategy of immersing oneself in music, placing technology as a barrier between oneself and the world during a time of grief. The way that the structure of the poems, moving from large or "monumental" as you put it to small or specific or minute for me mirrors in a way how this can be the experience of loss or grief—that there is something huge/intangible/incomprehensible but in the end what we remember is the specific sound, place or detail. I think that remembering detail is a way that we cling to our experiences; it was *this specific* shade of colour, it was *this specific* kind of laugh*, it was cold out, it was a Tuesday. Once I described this project to a friend and she said, "Oh, I don't think those are miniatures, those are needle biopsies" and I found that very apt. It can be a painful process to extract or uncover. SJS: In the notes and acknowledgments section of the book, you mention that there was a last minute title change from I know how small a story can be to The things I heard about you? What prompted this change? AL: (a) I know how small a story can be is a cumbersome title (b) I was embarrassed by how self-important it sounds (c) Smug? (d) Sometimes a title is the name of the Microsoft Word Document you made and it isn’t actually the title of your book. It is important to know the difference. (e) A title can take you through a process as a touchstone for your process, but you need to move on from it when you need to, like a name that doesn’t fit you anymore. SJS: What are you working on now? AL: How to stay balanced while a full-time grad student and a writer. How to not be overtaken by institutional environments. I’m working on two projects. My collection of stories People Who Disappear was published by Freehand a couple years ago and I’ve been working on short stories since then. One, “Stories Like Birds,” you can read online at Lemon Hound. Another, “The Sandwich Artist,” will be in Prairie Fire soon. The collection is coming together. It’s called We All Have To Eat. Stories take me a long time. I’m also working on a collection of prose poems/experimental prose pieces called Vancouver For Beginners. These are pieces that look at Vancouver, my hometown, from many fractal perspectives. It’s inspired by texts like Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino and feria by Oana Avasilichioaei in terms of how they approach the city as an imagined space. Some pieces from that project have been in EVENT, The Capilano Review, filling station’s issue devoted to experimental writing by Canadian women, Dreamland, and Descant. A piece from the project will be in Best Canadian Poetry In English 2014, edited by Sonnet L’Abbee, with Tightrope Books, an anthology I’m proud to be part of. It’s out in November. I’m also working on another fiction project that at this point is mostly research; that one will take a very long time. ALEX LESLIE'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed