RUSTY TALK WITH STEVE RODEN dark entries 1, 2015 dark entries 1, 2015 STEVE RODEN (Los Angeles,1964) lives and works in Pasadena, California. His work includes painting, drawing, sculpture, writing, sound, film/video and performance. Much of his work begins with something someone else has made: be it a postcard from Walter Benjamin’s archives, a 1964 Domus magazine or issue 85 of Green Lantern Comics. His working process includes both found and self-made systems that influences the process of making. Recent activities include: DAAD residency at the Walter Benjamin Archives in Berlin; group exhibition “Silence” at the Menil Collection, Houston; “Rag-Picker”, CRG Gallery, NY; “In-Between a 20 Year Retrospective” at The Armory Center for the arts, Pasadena, CA; Chinati Residency, Marfa, TX. Civitella Ranier residency, Italy. In 2008, Roden directed a re-visioned version of Alan Kaprow’s “18 happenings in 6 parts” at LACE in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles (LACE). From 1978-1982, Roden was the singer for the LA punk band, “Seditionaries”. Since 1993, he has released over 40 solo recordings on various independent record labels. Rodenhas representation with gallery Susanne Vielmetter LA Projects, Los Angeles, and CRG Gallery, New York. DAVID POOLMAN: You’ve been involved in a variety of projects since the early 1980s and were part of the LA punk scene in the late 1970s with your band, Seditionaries. How did you come to work in music, sound, and visual art? Steve Roden: well, it’s hard to say. i mean as long as i can remember i have wanted to make things - be they images or sounds, etc. as a kid, i was always drawing, and my mom made stained glass windows with a friend in our garage, and my father was also very artistic. i was lucky that my parents gave me once for my birthday a small super 8 film camera and once also a small portable cassette recorder - so at a young age, i was working with machines and “technology". after getting the super 8 camera, my friends and i made a film about a time machine … it was a simple thing, but we spent a lot of time creating it. so overall there was some atmosphere of making things - being creative. my parents were relatively progressive, in that they let me follow my own path. when i became part of the punk scene, and started a band with some friends, there was no tension with my parents and no fights about my blue hair! a lot of my friends’ parents had fights with their kids because of how they dressed, etc. but i never had those kinds of fights with my parents. certainly drawing and painting as a child was very important for me - and really i never wanted to do anything else … and truthfully my practice is just an extension of my childhood - with a need to have a lot of “play” and to roam (now more mentally than physically). i don’t think i was ever made for doing practical things. it is kind of a cliche’ but the punk scene resonated through my young life so richly because we weren’t looking for fame and “fortune”. we were, at age 14 or so, looking to have a voice. along with being immersed in an alternative culture, this was during a time the government was thinking about reinstating the draft, so we had songs (i wrote the lyrics and sang - i should say, shouted!), one about anti-religion, one about ronald reagan, etc. we weren’t super political, but we were aware of things … it was an accidental plunge into the early los angeles punk scene that got me and my friends starting a band. again ... we had no interest in perfection, we simply wanted to find our voices as young teenagers, trying to create something different than our parents, or popular music. for us, it was about finding ways to create without boundaries. we never worried if our music was good - it was more important that we experimented in many facets of our lives. a lot of people look down at amateurs, but amateurs make decisions differently than someone trained. dubuffet’s ideas and his works come out of a similar place - with art brut - and i’ve always felt a resonance with things that have rough edges, as they feel, to me, more “real” so to speak than, schooled things. a big part of punk was anti-technique, more visceral, raw, etc. in truth, over the six years i spent in art school, i never learned any real practical techniques, and i think the lack of practical techniques, helped me … it sounds funny, but i do think that my lack of “proper” painting, color wheels, etc. i never connected to it, because i felt i was using someone else’s method. a lot of people who make things are worried about whether a thing is a good thing or a bad thing, but the resonance for me is the process … what do i learn? how can i learn? and which is more important - the making or the made …? for me that is an ongoing conversation, and even now, i still don’t know how to mix colors based on color charts, etc. i’m an improviser in general, and also i am interested in chance (obviously john cage is a huge influence), and what i see in cage’s practice, is finding different ways to do some something … and a real deep inner conversation about how to create strategies to debunk one’s personal taste … but when people talk about personal taste, it tends to be about the objects (or words, or moving images, etc.), but for me, cage’s ideas are about how one can work with materials creatively - meaning to create situations for yourself, to do something in a different way … for example, every once in a while, i walk from my house to my studio backwards. it’s a stupid thing, but on those mornings, i am seeing the view backwards. it changes my perception, and i see things i don’t see when i walk to the studio “normal”. i’m not very creative with total freedom, and i need rules to break, something to bounce off of. i think that’s why so much of my works tend to be a conversation with an object or a sound or an idea that is related to something in the world made by another human - i mean i am a total geek about certain artists’ works (and by the term artist i mean not just painters, but filmmakers, music makers, architects, etc.). DP: In looking at the diverse range of work you have produced over the last 25 years, collage, sampling, and repurposing materials is paramount. How do you go about choosing source materials for your various projects? I’m thinking, for example, about your use of sheet music in your deconstruction-reconstruction collages (2013) and the use of Walter Benjamin’s notebooks in your 3-channel video installation, shells, bells, steps and silences (2012)? SR: the truth is that i’m an art geek, and as such, a lot of my work has been inspired by other people’s work. i don’t mean that i make paintings about other paintings, but using something like walter benjamin’s notebooks, where i can sort of converse with the spirit of his works, or even with cage’s 4’33” i used the score to determine measurements of physical things, instead of times … and translating inches into seconds) DP: Who are some of the artists, writers, and musicians that have influenced your work? SR: whoa that is a large list … off the top of my head … arthur dove, john cage, myron stout, jess, wallace berman, robert bresson, guru dutt, alvin lucier, fluxus, rilke, alfred doblin, georges perec, yasujiro ozu, nick drake, brian eno, gego, can (the band), jack kirby, neal adams, stan brakhage, arvo part, r.m. schindler, john lautner, hans jenny, fred sandback, helen mirra, ruth asawa, hank aaron, vin scully, roscoe holcomb, par lagerkvist, frederick hammersley, oskar fischinger, harry bertoia, gary panter, joseph cornell, mary bauermeister, allan kaprow, john coltrane, my friends, my parents, and a lot of bands … a really lot of bands … ha! DP: In your article beginning and ending with trains on a table (2008), you discuss the ability of certain images to remain in our minds unconsciously and continue to have an effect on us. In particular, you mention a photograph of toy trains you purchased at a flea market. Are there other images that have stuck with you and influence the work you produce? SR: yes, of course. i’m a “picker”. for many many years with my friend dan goodsell, we would go to the flea market at 5 am, to look for things to re-sell, but also to pad our collections. it’s funny, because i started buying old photographs of people holding instruments or making music or sound, mostly from the early 1900s. for me there is always this weird moment where a single object or image opens a door. the first photo was a picture of a guy sitting next to a coyote, and i realized that while i was looking at it, i wanted to hear it. so i started collecting images, mostly from the early 1900s and this is a kind of way for me, to find a “nugget” and to see if it has “wheels” so that it might offer a conversation … hopefully long term. and my discovery of that one photo, was the beginning of a long gathering of photographs, and eventually that collection became a book, published by dust to digital, called i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces - in an attempt to create an atmosphere of sound in photos, and also with two discs of old 78 rpm records. but this is how things happen for me. to be open to a possibility - to find an image, put it on my shelf for awhile and over time it suggests a move or a reading or an idea, and over time … it became a “thing”, in this case in book form, and a sharing of things that resonate for me, and to offer such things to others. i’ve been a collector of things my whole life, and again, i’m probably closer to most objects than most people … DP: How does chance play a role in your work? SR: it is always present ... in decision making, and also to recognize that any situations offers choices, no matter how “bland" or “stiff” or “empty" or “dry” … and so for me, chance is a way of reading or reacting to a situation that i did not set into motion. necessitating moves that would not have come to be without them … chance for me is about making decisions without knowing the outcome. in my practice, i have a hard time with 100% freedom, so chance offers me a kind of disruption - more like a problem, than a good fit … it is also about working with parts that don’t seem compatible, or resolvable. i guess, i’m trying to say that i don’t look for situations that are determined from the start … to create something in mind and execute it. for me, that is of no interest. i need a kind of struggle, and chance or using scores, or systems, they offer me different ways of engaging with materials (some that are friendly and others difficult). DP: You have collaborated with artists such as Steven Vitiello, Frank Bretschneider, and Steve Peters. Can you comment on some of your collaborations and the collaborative process? SR: collaboration can be symbiotic or very tense. with the three folks you mentioned, well, the three you mentioned were full of ease. and many of those works seemed to kind of evolve on their own. of course, all three of us are improvisers, so there never really was no need to protect territories or who is in charge. certainly i’d rather work with folks who don’t have huge egos, but tension in collaboration can be really powerful as well. i would say that my aesthetic, certainly with stephen and steve peters, it was like an extension of family … and with frank it was the same … i think stephen and steve and i actually move in a similar pace, our work, our humanness, etc. even though frank’s music tends more towards beats and electronics, and my own tools are more analog and object based, there was, as always, an openness, and when we started playing (without talking much), it was the same … i mean it isn’t about who is using what language or what tools, but how do we find a place within our works and to respond to each other. i’ve had some bad collaborations, but that was mostly because of ego, rather than the actual works. that’s why i’ve worked with stephen and steve peters, several times, and if i lived in berlin, i would certainly want to work with frank more often as well. the process of improvising with friends is incredible, as if we speak our own languages and they start to morph into each other’s. again, it tends for me it works if everyone leaves their ego at the doorstep. DP: What was your motivation/interest in returning to painting? SR: really the motivation came out of a feeling that i was on top of my game, and felt that if i stopped painting for at least a year that things might change and my work might change. i know a lot of artist’s protect their brand or their visual language etc. for me, i didn’t want to feel like i knew what i was doing, and, i needed more difficulty … to feel more like an amateur, trying to find my way. i joke with friends a lot about “pulling a guston”, which is what i hope to manage to do at some point. i love the stories of when morton feldman saw philip guston’s late works, feldman felt that guston had betrayed feldman … i mean if you look at guston’s early paintings you can literally hear feldman’s work while looking at those canvases, but when you see giant heads with clan hoods, and cigars, and eyes, and flashlights, etc. the shift was so strong, that people were pissed off. what’s super great is that the uproar wasn’t about language or pornography or various “edgy” materials, but guston wanted or needed to say something that would shatter what he had been doing. it was pretty darn brave … so my motivation is to attempt to climb a similar mountain where the work can feel visceral and human but at the same time, to remain an improviser and to follow a thread … no matter how thin it might seem - especially at the beginning. so i’m trying to make paintings differently. i feel that if i disrupt the process, the works will change. DP: What are you currently working on? SR: two things: one is that over the past three years or so, i have been making sound with a modular analog synthesizer. it came to me through some friends, who suggested i play around with it. what’s great about it is that after three years of puttering, i still have very little knowledge of what i’m doing. but also, it’s complicated enough that i regularly have to watch demos on youtube or ask friends, what a such and such will do … stephen vitiello and i started around the same time, and we did a gig together in france, and as we started the gig, we both plugged in cables and turned knobs, and at one point stephen tapped me on the shoulder and quietly let me know that my synth was not making a sound!!!!! and it took me a while to get it running, and i was petrified, but it was proof that this seemingly “stiff” machine could offer some serious accidents. and so, the use of new tools, without much learning, there’s a lot of frustration, but there are also moments of great understanding. in some ways, my earlier works were a bit precious, certainly intimate, but always quiet … so i’m also making loud things … as it is the nature of the machine. as for painting, i’m just beginning again. my last show of the first paintings made over a year and a half away from painting, i’m slowly trying to push some of the ideas of those first paintings without a year of painting, and so it is slow going, which is great, and every time i feel something that is familiar, i push it back. and i hope in some way people will find them different, hopefully quite different, so that i can use these works as evidence as a human attempting to grow through the ins and outs of a medium that continually kicks my butt. David Poolman is the Visual Art Editor for The Rusty Toque.

RUSTY TALK WITH VICKI LEAN

|

"Canadians like to think we have this loving, egalitarian wealthy society. But we don’t. We have communities that have the highest suicide rates in the world." |

Victoria Lean: I was making bizarre home movies with my neighbors from when I was about eight, and I wanted to be a professional documentary filmmaker ever since I was a preteen. My parents are environmental scientists, and I spent a lot of my childhood at their field station (on a lake) where many other scientists and grad students would visit. The rest of the time I was in downtown Ottawa. Growing up in the country’s capital, I felt there was a profound disconnect between academics, politicians, activists and the general public on the kinds of environmental issues my parents and their colleagues were studying.

Believing that film and media held the key to dialogue and change, I pursued an undergraduate degree at McGill that straddled film studies, international development, and environmental studies. Through this more activist approach to filmmaking, I fell in love with craft. Living in Montreal for my undergrad, I was shooting and editing music videos and live shows, including an experimental short for the NFB.

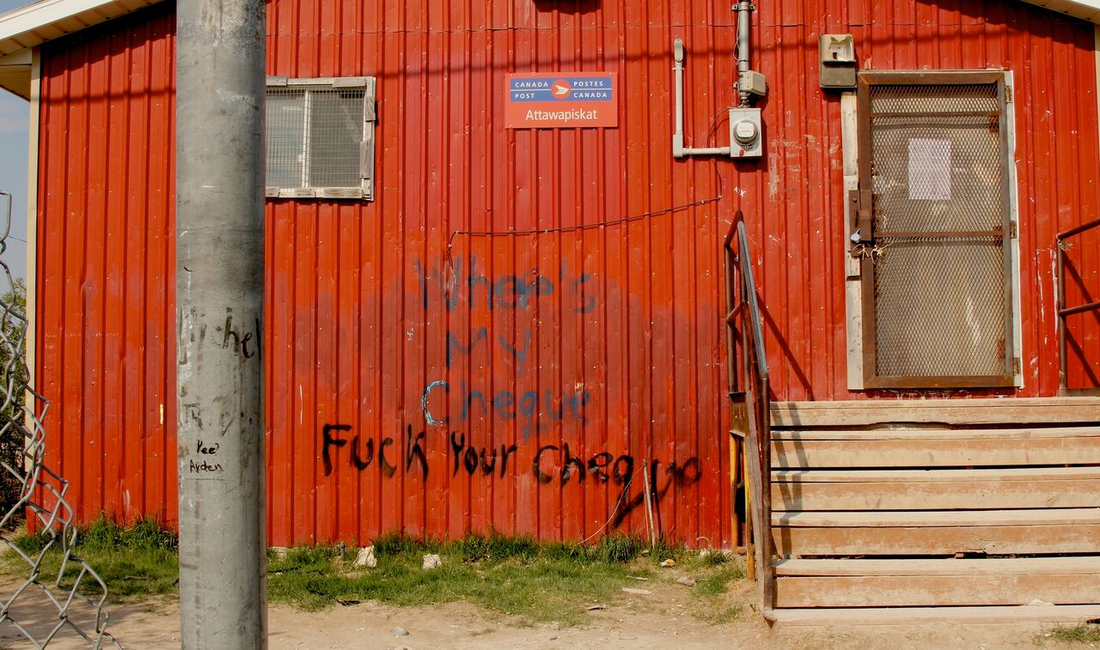

Soon after completing my undergrad, my dad brought me along on a visit to the remote First Nation’s community of Attawapiskat in Northern Ontario. After witnessing the tremendous injustices facing the reserve, I decided to assist in the community’s efforts to raise awareness of their situation.

I embarked on an MFA in Film Production at York University to develop what would become After the Last River. It is pretty much my first film as I have not submitted anything else to a film festival before. I had no idea what a challenging, but hugely rewarding, journey it would be.

MV: So you first became aware of the Attawapiskat community through your father’s work?

VL: Yes, that’s right. My father, David Lean, is an ecotoxicologist and freshwater scientist who specializes in mercury release in wetlands. Over a decade ago now, he started raising concerns about the De Beers Victor Mine, which is still Ontario’s first and only diamond mine, and how it would be draining large amounts of water from the wetland, resulting in potentially higher levels of mercury in the fish eaten by the local community.

Around 2008, he was going to be an expert witness in an Application for Review filed under Ontario’s Environmental Bill of Rights that challenged the De Beers project—but it didn’t go forward. The pro-bono environmental lawyers involved at the time explained to me how hard they found it to represent people in the far north—both because of geography and language barriers. Two weeks after the mine opened, I went on that first trip to Attawapiskat with my dad and two environmental groups, EcoJustice and Wildlands League. Concerned community members had invited them to discuss potential environmental impacts from the De Beers mine, especially those involving mercury levels in the local fish.

MV: What drove you to make a film exploring these issues?

I made After the Last River because I wanted to help bridge a large gap between different groups of people—driven far apart by geography, language, culture, histories and experiences of colonization.

In the early days of the project, I was specifically drawn to investigating the environmental issues surrounding the Victor Mine. Before the diamond mine opened, the Attawapiskat River formed part of the largest pristine wetland in the world. The deep layers of peat in the James Bay Lowland store 26 billion tons of carbon, which contributes to roughly one tenth of the globe’s cooling benefit. This was also one of De Beers’ first mines outside of the African continent, so that was interesting to me given the company’s troubled history.

When the mine opened in 2008, I witnessed the Victor project receive little media attention and arguably inadequate government review, and so I returned in 2010 to document the impacts of the mine on the community—both the negative and the positive.

However, upon arrival, I realized the deeper story was beyond my environmental lens. It was rooted in the vast disconnection between the reality of Attawapiskat and the myth of Canada. Attawapiskat struggled to benefit from economic development opportunities such as the De Beers Victor Mine because of factors beyond what a mining corporation can address—a lack of housing and social services such as family counseling, health care, youth programming, and education.

MV: What was the first step in terms of getting the film going?

VL: My first step in 2010 was getting permission of the Chief at the time, and then finding a place to stay and finding a local contact and activist working on these issues.

In creating the film, I spent over 80 days in Attawapiskat before the community shot into the national media headlines during the housing crisis of 2012 and again during Idle No More in 2013. I was deeply troubled by some of the coverage of Attawapiskat and Idle No More. The reaction of many Canadians, including Prime Minister Stephen Harper, was effectively to blame the community for its misfortune. Meanwhile, significant structural and historical explanations, such as the inability to share in resource revenue and chronic government underfunding, were hardly touched on.

One of the goals of the film is to highlight what was overlooked in the mainstream media and to draw attention to the intersection of various problems: for instance, how housing issues are also educational, health, mining, and political issues. The ultimate goal of the film is to encourage greater understanding of Attawapiskat, and to encourage southern Canadians to think about how their own wealth relates to remote First Nations communities like Attawapiskat. I wanted the film to hold up a mirror: After the Last River is not simply a portrait of Attawapiskat but a portrait of how Canada treats Attawapiskat and places like it.

MV: Were people from the Attawapiskat community reluctant to trust you as an outsider?

VL: They were receptive—but I think maybe a bit skeptical—I was this 24-year-old student when I started the film, I was there by myself—what did I know? what could I do?!

But there was a lot of warmth. People welcomed me into their homes, and Rosie and her family (who are featured in the film) certainly took me under their wing. Keep in mind when I started the film, I believed--

like many community members—that if only Canadians knew what was really going on then things would be different. People were very eager to spread awareness regardless of the medium or who was doing it.

I also had the unique privilege of spending some significant time in the community. Beyond working on my film, I joined in several traditional ceremonies, staffed the door at the high school dance, and helped distribute food donations. This activity was driven, in part, by an awareness of a long history of non-indigenous people coming to indigenous communities, asking about people’s lives, documenting their stories, leaving and then never being heard from again. As such, my filmmaking approach was rooted in investing time in making the film (five years) and living in the community (over 80 days). Before breaking out my camera, I spent time learning about Attawapiskat and participating in events and daily activities.

I believe that sharing filmmaking skills is an important means of giving back to the community. On my second trip to Attawapiskat in summer 2010, I assisted with video workshops surrounding youth suicide prevention and a garbage cleanup. During this experience, I met and hired a local youth named Trina Sutherland as a production assistant. I also organized a sharing circle between local elders in Attawapiskat and elders in Toronto over Skype as part of the Earth Wide Circles project. For the third visit, I assisted my thesis supervisor, Ali Kazimi, in collecting video and editing equipment and I led a video workshop along with my cinematographer, Kirk Holmes, to train local youth on the equipment.

MV: Is there a filmmaker or writer (or more than one) that has had a particularly significant influence on your work in general and/or on After the Last River in particular?

VL: For After the Last River, there’s been a few. While the storyline of After the Last River evolved over the years, my approach remained influenced by Susan Sontag’s last published book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). Sontag argued that when photographing dire circumstances of human suffering, the goal of the photographer should not be to elicit the sympathy of the viewer, but to encourage the viewer to contemplate how their own privilege is complicit in that suffering.

As I made the film, I thought a lot about how often images and stories relating to First Nations poverty appeared in mainstream media, but how little impact they seemed to have. Sontag proposed that "for photographs to accuse, and possibly alter conduct, they must shock,” but that shock can become familiar, people do not want to be horrified, and they simply change the channel.

In reviewing online comments on Attawapiskat news stories, it seemed that for some people, compassion was already stretched to the limit. It was my challenge to try to engage audiences that may have already tuned out, and this meant not focusing heavily on imperatives or moral obligations, but highlighting the community’s stories of resistance and strength with also some pretty awesome humor from up there.

The cinematography of Todd Haynes’ fiction feature, Safe (1995) also served as inspiration as it visually explores the presence of environmental toxins in human spaces.

MV: Your first person narration to ties together the complex intersection of issues the film is dealing with while also relating your own connection to Attawapiskat (through your father). Was it always a part of your conception of the film, or did it come later in the process?

VL: I definitely did not plan to do first person narration when I started. But after Attawapiskat hit the news, I came to recognize that a general account of Attawapiskat’s situation would not contribute much, especially given the many journalistic pieces that already existed on the community.

My own gradual recognition of the extent and complexity of Attawapiskat’s (and Canada’s) problems became a vital thread. The point of departure for story development was more about my intimate experience of the community in order to encourage a more relatable connection with the people in Attawapiskat. It was also important to foreground who I was and why I was telling this story—so that it didn’t seem like an authoritative account coming from the community itself.

Josh Fox’s Gasland provided a reference for a how a documentary dealing with environmental impacts, corporate greed, and resource extraction can be intertwined with a personal story and journey. I intended to provide a feeling of ‘bearing witness’ rather than making a direct argument. As such, my personal journey to Attawapiskat and the backstory with my father served more as a subtle, structural backbone, similar to how Eugene Jarecki used his personal story with his African-American caretaker to enter into a critique of America’s war on drugs in The House I Live In.

MV: Given the potentially problematic issues that can arise when a white filmmaker from a big city depicts a marginalized culture and community, did you have any doubts about making yourself a character in the film?

VL: I had many doubts and certainly there were many pieces of voiceover that were taken out since they felt a bit too much like ‘white girl going on a journey’. I’m grateful to my editor, Terra Long, for a lot of her coaching on that. There were also a couple stories I told in VO, particularly about a suicide attempt, that I actually removed. I didn’t think I was the right person to voice that story. Instead, that event is gestured through the suicide awareness march with no dialogue.

I always think it's important to question who is telling a story and why they are telling it. I was also questioned a lot and it was important to qualify my personal connection to the place.

But at the same time, Attawapiskat is in my own province. The situation in Attawapiskat is a Canadian problem (not simply an Indigenous problem). Part of taking collective responsibility for our shared history and the current situation, involves having the ability to respond. So this is my response to the tragedy that our country has inflicted on remote First Nations communities.

MV: In everything your learned while researching Attawapiskat and the surrounding issues (the Indian Act, etc), what surprised you the most?

VL: There are so many things that surprised me! As I followed the isolated community’s rise into the international spotlight and the Chief’s role in the indigenous rights movement Idle No More, I was really surprised by what a disturbing blind spot exists when it comes to First Nations issues.

What surprised me the most was that Canadians are deeply divided along racial lines—I didn’t realize how bad it was. Most have been taught little of Canada’s historic relationship with First Nations people; curriculums rarely mention treaty obligations or the many human rights violations against indigenous people. Historical ignorance and geographic distance have disconnected consumers from where their resources come from, and this ignorance and distance isolates First Nations from those in power and from other communities—both aboriginal and urban. Canadians like to think we have this loving, egalitarian wealthy society. But we don’t. We have communities that have the highest suicide rates in the world.

It was shocking to see how many Canadians reacted when they did find out about the community’s struggles through the mainstream media. The film wasn’t just about a community struggling to be heard anymore, but a country’s reaction to it when it finally is heard. My film definitely touches on the important role that journalism plays in disseminating information, but also on how damaging journalism can be when it’s being influenced by a political agenda or contains problematic information. So that was surprising—the level of misinformation that was getting published in important papers.

One of the themes that comes up a lot in Q&A’s is the “death of evidence.” In the case of Attawapiskat, there is very little research available on things like government funding levels to reserves, mercury levels in fish, and the relationship between a the 30-year diesel spill and the number of children in Attawapiskat with autism and leukemia.

MV: One of the most disturbing parts of the film for me was the way Harper’s PMO so effectively controlled the narrative about Attawapiskat by throwing around manipulative stats and figures to shirk financial responsibility for providing aid to the community. They suggested that the problems were due to financial mismanagement and even criminal fraud on the part Attawapiskat leaders, and the press took this seriously without much investigation into the merits of the accusations.

VL: After Harper insinuated that it was the community’s fault, that they have mismanaged the funding, the whole story changed in the press. In the resulting blame game, Chief Spence was targeted in racist comments, political stump-speeches, and op-eds. Sun News in particular was pretty hard on the community and fairly indiscriminate in their coverage—they even took photographs from the university website that I had taken during the youth video workshops in Attawapiskat and plastered “financial mismanagement” over top of them. It was horrifying.

MV: What, in your view, are the biggest misunderstandings that persist in the general public about Attawapiskat?

VL: People don’t realize there is a two-tiered system in Canada—First Nations people do not get the same opportunities and funding levels that non-indigenous communities do. They don’t have the same level of education, of housing, of access to drinking water, the list goes on. For instance, a First Nations child’s education is funded by $2,000 to $3,000 less than a child in a provincial school. And we don’t even know exactly by how much schools are underfunded.

Another misunderstanding that came up again recently, which people just don’t seem to want to shake is this tired old question—“Why don’t people move, why do they stay in these communities if they are so bad?’ People just completely misunderstand the attachment to land and the importance of community—and also that a lot of indigenous people don’t often do better away from their families when they move to the city either. For one, being an aboriginal woman in this country means you are several times more likely to be murdered than anyone else.

MV: Have you had any response from De Beers about the film?

VL: Yes! The rep from De Beers (who appears in the film) came to the very first screening, which should have been private. It was my MFA thesis defense, and it wasn’t posted on the internet, but they found out. It was a tiny screening—just me, my supervisor, two friends from film school, the two external examiners who were grading me, and then De Beers and a rep from mining lobby group, PDAC. He sent me a seven-page letter with “notes” afterward. I cried on my bathroom floor that day because I was worried my film would never see the light of day after that.

But luckily it did. And when I had the Toronto premiere, the same De Beers rep came again and when I was going into the screening he said, “you’ve had a good run so far!” I told him I got his letter and carefully considered his notes for this final version.

He sat in the back and then when the movie ended, he talked to every single Attawapiskat community member that was there on their way out, the NGO reps that are in the film, my dad, me. He said he was pleased to see some of his notes considered, and was being incredibly nice (and maybe because I’ve spoken publicly in the past by how intimated I felt by him before).

MV: This may be unfair to ask you, but it’s something I always wonder about … Even if De Beers doesn’t care about the community at all, it seems like it would be such good PR to donate money for Attawapiskat to build, say, a new school—and the amount of money would be relatively miniscule compared to the profits they are making … Why do you think they don’t do more—if only for the sake of their own image?

VL: I’ve asked them this question directly—the simple answer is that they are not in the business of building homes or schools. I’m paraphrasing, but they will say that this isn’t some developing country where government has no capacity—and it isn’t their job to replace the role of government. In some ways, they are right, it isn’t there job. And it points to just how much the Canadian federal and the Ontario provincial governments are not doing their job.

De Beers believes that jobs and business opportunities are more sustainable ways of giving back—but they didn’t fully comprehend the degree to which Attawapiskat has been systemically marginalized and how that has impacted the community’s ability to take advantage of these types of benefits. The workforce simply wasn’t ready mainly because the community never had a proper school, and also there weren’t enough homes for local workers to remain in the community (as a result many qualified people that work at the mine had no choice but to leave Attawapiskat).

MV: Can you tell us a bit about what has been happening there and with De Beers since you finished filming?

VL: The film leaves off with the possibility of De Beers expanding—of mining (Tango Extension) another one of the 17 kimberlite bearing pipes on Attawapiskat’s traditional territory.

Since the film was released, Wildlands League (the environmental group in the film) published a big investigation into the failures of De Beers’ own environmental monitoring. De Beers has subsequently reassured the community there are no significant environmental impacts. Currently, the community is divided in support of Tango Extension for a variety of reasons. Because of some local pushback, De Beers has stopped exploration of the new site that would extend the life of the existing mine, which is set to close in 2018. I understand they are already starting to wind things down—so it's sad in a way, the mine was only open 10 years and so far, it seems like the expectations for the prosperity it would bring outweighed the reality.

De Beers also build another Canadian mine the same year. And they recently shut that mine early—citing a downturn in the market. But there were some pretty questionable environmental impacts they did not foresee that played a part in it closing.

MV: Attawapiskat has been in the news again this year with the alarmingly high number of recent teen suicide attempts. Do you have any thoughts on this from your experience with the community?

VL: It’s difficult even for people in the community who have kids of their own to explain and understand what is happening. It is not a mental health issue really—it’s proven that people do not do well when they don’t have the basic necessities of life—food, clean drinking water, proper shelter, etc. As a young parent, not being able to give these things to your children is heartbreaking. On top that, the prospects for jobs and employment opportunities are dismal. Some youth have given up hope and there isn’t much to engage them—like after school programs or career training programs. And on top of that, I’ve heard that the drug and alcohol problem has gotten worse, and of course it’s very difficult to provide any counseling or support. Youth that are suicidal are sent out for psych assessment, and are back in a day or two and there is no one following up on them.

There is also some research that explains how suicide is “contagious”—especially among teenagers. Some of the worst nights in terms of the number of attempts also involved suicide pacts. It’s tragic, and its been developing for many, many years. It also has its roots in the trauma of residential school, which is often passed on through families.

There’s a lot of work that needs to be done on all fronts—and I hope the film contributes to conversations about a more sustainable and fair society in Canada.

Still from After the Last River

Still from After the Last River

AFTER THE LAST RIVER

Documentary

90 minutes

2015

Website

Screening

Canada wide – July 1, 8:00 pm EST – CBC Documentary Channel

Check with your provider for channel information.

Synopsis

In the shadow of a De Beers mine, the remote community of Attawapiskat lurches from crisis to crisis. Filmed over five years, After the Last River is a point of view documentary that follows Attawapiskat’s journey from obscurity and into the international spotlight. Filmmaker Victoria Lean connects personal stories from the First Nation to entwined mining industry agendas and government policies, painting a complex portrait of a territory that is a imperiled homeland to some and a profitable new frontier for others.

RUSTY TALK WITH TAMARA FAITH BERGER

| Tamara Faith Berger has published three novels: Lie With Me (2001), The Way of the Whore (2004) and Maidenhead (2012). Her first two novels were recently re-published as Little Cat (2013). She has been published in Taddle Creek, Adult and Apology magazine. Her work has been translated into Spanish and German. Tamara won the Believer Book Award for Maidenhead. She lives in Toronto. |

I feel more powerful now than I ever did.

Tamara Faith Berger: Yeah. I personally have a lot of unexpressed anger myself. That is also what I want too. There are a few movies like that and you’ll have to tell me what movies you’re watching that are good like that. I sometimes see movies that have more Taxi Driver or even adventure. It’s like an adventure story, right? Getting something out that we don’t normally see and it wants to be in public. I don’t think this could purely happen in public. It has to be ratcheted up a couple of notches. Maybe one day... I don’t know. I want to see things played out that I don’t see. It’s like in a dream.

I just actually took a self-defense course for women and I had never done that. It was amazing.

JV: Reminds me of the danger aspect in the book.

TFB: I guess, that book, Kuntalini, ignores danger and I know danger exists. But I like that I can make this little story where a female can do whatever she wants, and get in a car with a bunch of guys and have a good time.

JV: The way you wrote it was very surreal in that respect.

TFB: Because of the danger, you mean?

JV: Yeah, the danger. Because you fantasize about stuff like that, but you don’t really play it out. I mean, maybe, you have times when you actually do, but you’ve still placed yourself in a very vulnerable position.

I feel like a lot of Toronto-based female writers like yourself write from a surrealist, magic realism perspective, like it is its own genre. Writers like Lynn Crosbie and Liz Worth. Is it something that comes to you?

TFB: I’ve never really been a realist per se, but I want things to be possible. I kind of go from reality and then something gets a bit too intense, but I still want to make it happen. I also don’t want to leave the realistic world. I can see that it’s like a genre, like you say, but I also don’t want it to be too surrealistic.

JV: What I find now, especially with your writing is that there’s an undercurrent of not just sexual revolution, but an actual revolution going to happen. I feel like women are finally going to just put everything down and start yelling, “Fuck this shit. We’re taking over,” and overthrow the powers that be. When’s the revolution happening, Tamara?

TFB: I feel like it’s a slow transitioning of power. There are some women and female artists that are way on the edge of us. I find that really inspiring.

There’s this woman, I don’t know if you’ve heard of her, Fannie Sosa. She does dance

and workshops. The stuff that comes out of her mouth about worshipping women—I don’t want to paraphrase what she is doing, just look her up.

JV: I’ve been re-reading a lot of ’80s feminist texts, which deal with a lot of more new age-y sort of stuff. Right now it’s Descent of the Goddess by Sylvia Brenton Perera. It talks about working through traumas through a Sumerian goddess myth.

TFB: Fannie Sosa is kind of like that, worshipping the cunt, but she spells it “khunt.” It’s pretty deep what she’s talking about with women and the patriarchy and getting rid of it.

There’s a lot of that now, like the eighties and nineties. There’s that large one too, When God Was Woman by Merlin Stone.

JV: A lot of this new age-y stuff makes sense though beyond logic. Maybe we have to go crazy. Maybe we have to decolonize. Maybe we have to take men out of the equation and rebuild.

TFB: I’m 44 and I like to think that I’ve come this far and men don’t have so much power over me anymore. I feel more powerful now than I ever did.

JV: There was this article called Rhythms of Fear by Laura Maw in Hazlitt. It talked about how cities, in their networks and architecture, aren’t built for women and that’s why they are so dangerous for women. Do you feel like you are not wanted in a city space or a street wasn’t meant for you?

TFB: Yeah, I think so.

Jacqueline: And in your writing?

TFB: It was easier to do it with this book because I could bullet through the chapters because it’s short. It’s like when she goes down into Niagara Falls and no one, really, is supposed to go down to Niagara Falls like the character does. That’s probably the most fantastical section in Kuntalini. I wanted Niagara Falls to be what I wanted it to be.

JV: And when she just starts walking along the highway with no regard to her safety. She’s trespassing a very unnatural space not made for her body in mind.

I think what I find great about your work and the genre you write is that it used to be that porn was written for a certain point, an ends to means. Your writing includes politics and subversion.

I was reading it and felt both stimulating and in need revolutionizing. It was inspiring.

TFB: It’s like excitement [...] like pornography, not that Kuntalini is porn, [..] but I also see it like propaganda. That’s why I find it very powerful to work in it. I can put out what I want to put out. I also write screenplays and it’s a bit difficult there because they usually place the woman in bad behaviour situations. But it’s just that, bad behaviour. I want to see it played out.

JV: Why do you think they say it’s bad behavior?

TFB: I don’t know. I mean, yeah, she’s masturbating in the taxicab and someone offered her coke and she did it. But she was still the master of her own world.

JV: Yeah, because if a guy did that in a book or in a movie, it would be considered artistic and part of the character’s ethos.

TFB: I think in other worlds like film, people don’t think that a female going about her day in a certain way and trying to get something done is a story enough.

I think that for adventure narratives, for lack of a better word, we see a Tomb Raider kind of Angelina Jolie character kicking butt, but not in a super sexual way. We don’t see that kind of adventure story for females. I think it’s good to put it in people’s minds—it’s excitement.

TAMARA FAITH BERGER'S LATEST BOOK

Kuntalini

Badlands Unlimited, 2016

| Eat ass, pray, love. Twenty-five year-old Yoo-hoo experiences a sexual awakening in her yoga class. She breaks up with her boyfriend and travels to Niagara Falls where she meets a cold fish teen prostitute and an ex-Army troglodyte deep in the falls. Yoo-hoo’s unforgettable yogic journey sweeps across the realms of asana, hysteria, enlightenment. Kuntalini by Tamara Faith Berger is one of the New Lovers, a series of short erotic fiction published by Badlands Unlimited. Inspired by Maurice Girodias’ legendary Olympia Press, New Lovers features the raw and uncut writings of authors new to the erotic romance genre. Each story has its own unique take on relationships, intimacy, and sex, as well as the complexities that bedevil contemporary life and culture today. |

RUSTY TALK WITH PAUL DUTTON

| Paul Dutton is a writer and musician with a 48-year publishing and performance career. A member of The Four Horsemen poetry performance quartet (1970-1988) and of the free improvisation band CCMC (since 1989), he has performed solo and in ensemble at literary and musical events throughout Europe and the Americas, has authored seven books, and released six solo and eight ensemble recordings. His most recent book is Sonosyntactics, selected and new poetry, edited by Gary Barwin for the Laurier Poetry Series. Find him online at pdutton.ca. |

John Nyman: At Rusty Talks we often ask writers about their first memory of writing creatively. Your career, however, has focused at least as much on your signature oral performance technique of “soundsinging” as it has on “writing” in any traditional sense, and you have said on several occasions that you see your work as “a continuum; pure music at one end of the spectrum and pure verbality at the other end” (Somerset). Considering this, what is your first memory of engaging in any creative activity, whether musical, verbal, visual, or something in between?

Paul Dutton: In my preschool years, when I got pissed off about something, I’d stomp up the stairs, blistering the air with the foulest language I knew: “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Stinkers and Bums!” That, at any rate, is how I have always remembered it, but my eldest sister recently insisted, quite adamantly, that what I shouted was, “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Bums and Stinkers!” And that has made me wonder if I perhaps reconstructed, from abiding family lore, my personal memory of my oft-repeated display of pique, complete with a mental image of my miniature self pounding up the staircase. Whether the memory I hold is truly mine or borrowed from accounts heard from family members, it’s clear that, somewhere along the way, I exercised a bit of aesthetic initiative, reversing the last two terms to create a skippier cadence.

JN: What would you say are the similarities and differences between your sound performance and your written work?

PD: Oh shit, I don’t know . . . [3 days later (because let’s admit it: I’m writing this, not speaking it)]: Okay. I’ve thought a lot about this. First of all, my work doesn’t in fact readily divide into “sound performance and written”: there are all kinds of gradations and overlaps. As well, there are plenty of similarities and differences within those two categories, not just between them: for one thing, I write print poems in no one style but throughout a wide range, including formal, free verse, minimal, narrative, with line breaks, run-on, found poems, etc. My sound poems range through a variety of styles as well. And then there are the visual poems, which are arguably as much drawn as they are written—if typing a bunch of punctuation marks, as in my Mondriaan Boogie Woogie sequence (two of which appear in Sonosyntactics), can even be called writing. I like to refer to the whole field of visual poetry as “drawing with the alphabet.”

So, we’re getting into distinctions and categorization here, which always make me feel uncomfortable. In so much of my work—and in almost everything else in the world—categories overlap or merge.

Anyway, there are no consistent similarities and differences between my soundworks and poems for reading (to substitute terms for your two categories). I have linguistic and non-linguistic poems in both of those categories. I have sound poems with words and fluid syntax, and “written works” with no words (single letters or phonemes instead) and fractured syntax. A number of poems fall into both of your categories, some with performance notes, some without; and some whose written versions have shortened passages of what would be extended repetitive material that works fine in performance but would be oppressive in print.

Since the late 1990s all my newly created soundworks have been totally improvised and almost exclusively nonsemantic, unlike the painstakingly worked-over poems composed for reading and recitation. I still perform repeatable repertoire works, which are likewise worked over, but I have long since stopped producing new works in that mode.

One consistent feature across the various categories that can be applied to my creations is that the individual works proceed out of themselves: I begin with some generative notion—a word, phrase, image, sound, whatever—and find my way by following the poem (or fiction), sensing its direction and development rather than imposing any preset idea of where it will wind up. In a pure-sound improvisation I of course move more rapidly through the process than when I’m working over something in a repeatable form.

Another consistent feature is concentration on the sonic qualities of language and of human utterance in general. This is reflected in the titles I’ve given some of my books (Sonosyntactics, Aurealities, and Right Hemisphere, Left Ear) and my two solo CDs (Mouth Pieces and Oralizations).

JN: How do you convey your creative efforts to the listener/reader when you have access to only one medium or the other?

PD: I’ve partially answered that already in the third and fourth paragraphs of my response to your previous question. Some of my sound poems are thoroughly worked out—what in music is sometimes referred to as “through composed,” though that typically means notating pitch, rhythm, phrasing, dynamics, and tempo, whereas I never specify pitch, rarely specify volume, and generally, both in sound poems and poems specifically for the page, leave various of those elements to be inferred, implying them by punctuation, line breaks, and distribution of the text over the page. I’ve one printed poem for which I’ve provided idiosyncratic diacritics, briefly explained; and several for which, as already stated, I’ve provided explicit performance notes.

JN: You often write about numbers—not mathematical equations, but numbers as quirky and surprising participants in dramatic situations. Why this fascination with the numerical?

PD: Maybe its compensation for my general innumeracy. You know, a fascination with one’s disability, or an obsession with an unrequited love.

JN: Your work contains many poignant references to time, especially in relation to performance and the body. For example “Milk-Cart Roan” opens with

breath breathe

time breathe

memory and breath

is

time

and breath

breathing (1)

PD: Hmmm. Time. Well, my readings and my musical performances of course operate within time constraints, either very tight (“No more than five minutes, okay, Paul?”) or very loose (“Take as long as you want”). Does that qualify as a connection? Well, here’s a for-sure differentiation: improvised soundworks are created within the time it takes to perform them, but a poem (whether a sound poem or a conventional print poem) that took me months to compose can be read in a matter of minutes or even seconds.

And then there’s content: an awful lot of my bookable poems deal with multiple aspects of time, either referring to or reflecting on various temporal conundrums, ambiguities, possibilities, illusions, and incongruities, among other time-related phenomena (like memory, for example). I’ve got a semantically based sound poem entitled “Time” that starts out with that word and moves through a developmental process to arrive at the word “untime”—which is another obsessive notion for me. But I’ll be damned if I can see a way to get any of that kind of content across within a nonverbal sound improvisation.

JN: Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry of Paul Dutton is the newest entry in the Laurier Poetry Series, collecting some of the best poems from your nearly 50-year career with an introduction by Gary Barwin and an afterword by you. How did Sonosyntactics come about, and what did you hope to accomplish with the collection? What was it like working with Barwin (who also selected the collection’s poems)?

PD: It’s an invitational series, initiated by the publisher or an independent editor, and Gary proposed it to Laurier—without my knowledge, of course, sparing me the disappointment of a possible refusal. Both Gary and I wanted it to be a collection that fully represented the multimodal character of my work and we’re both satisfied that it is.

The concept of the series is to present 35 poems by any given author, which we considered unworkable at the outset, so just went our merry way but kept it within range of the more-or-less average page count in the series. I mainly left it up to Gary to choose, but twisted his arm over a few poems I felt had to be in there for one reason or another. He has either a supple arm or a high tolerance for pain, cuz he didn’t cry out too loudly. To switch the metaphor, we saw eye to eye on almost everything.

JN: For me, one of the most striking parts of Sonosyntactics is “Lines on a Line of Kurt Schwitters,” a multidirectional matrix of typewriter lines riffing on Schwitters’s “Decide for yourself where the poem begins.” The collection as a whole presents us with a variety of reading challenges whose solutions we do have to “decide for ourselves”: branching paths nested in long footnotes (“Uncle Rebus Clean-Song”), extremely dense and repetitive prose (“A Little Light Love,” “Thinking”), and performance notes far longer than the “poem” they annotate (“Mercure”), to mention just a few. What role does choice play in your writing, both for you as a writer and for your intended or imagined reader?

PD: A choice I make with each poem I write is to compose it either with line breaks or as run-on text—what is usually called prose poetry, a term I frankly find pointless. I myself would never designate such works as “A Little Light Love” or “Thinking” as prose. They are poems, plain and simple, and a qualifier such as “prose” is neither necessary nor helpful. Surely what makes a literary work poetry is the character of the writing, not the way the words are laid out on the page. There’s an awful lot of prose getting published that’s written with line breaks.

Writing is, of course, very much a matter of making consecutive choices, either instantaneously or over the course of minutes, hours, days, even years. Yeats somewhere (in a poem, I believe) characterizes poets as staying up all night in pursuit of a single word, which is a circumstance I can relate to. Even in this little exercise, I’ve gone back and forth between alternate words or phrases, or else have revised words or passages that days later I found unsatisfactory for one reason or another.

As for the reader’s part in this equation, well the first choice is, obviously, to read or not read the material at all. Then a reader can choose to read silently or aloud, to imagine or attempt a performance of poems I’ve provided descriptive notes for, to heed or ignore my line breaks, to interact creatively with the text or let the words glide past, and in the case of “Uncle Rebus Clean-Song” to read the first thread straight through or else wander off down one of the side-trails. I wish I’d not used footnotes for the various narrative branches in that little fiction (which I don’t actually consider to be a poem, by the way), because the footnote implies a secondary status. Nichol used a more satisfactory method in The Martyrology Book 5, where superscripts offer the option of turning to another section of the book in the same font size, so there’s no hierarchical implication.

JN: “The Eighth Sea” stands out in Sonosyntactics, both for the range of its performative strategies (from matter-of-fact cataloguing to full-on improvisational soundsinging) and for the political force of its themes: colonial violence, environmental destruction, and the collision of settler and indigenous languages in the Great Lakes region. What do you think the creative techniques you have pioneered throughout your career can contribute to deeply political conversations such as these, both in Canada and abroad?

PD: Yikes! I’ll have to leave that for others to say. I do know that my good friend John Beckwith adapted some of the devices used in “The Eighth Sea” for structuring his 2015 oratorio Wendake/Huronia, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Champlain’s arrival in Huronia. I can’t imagine how to calculate the effect such works might have in the social or political spheres, but I suspect that it’s not significant. I prefer direct activist involvement as a more effective and appropriate avenue of influence in those areas. I’m not a fan of what I call propagandart—didactic or utilitarian works—however much I might applaud and revere the causes espoused. I’m out to create, not preach. I prefer to leave any political stances implicit in the artwork, and focus my attention on the aesthetic and spiritual realms, aiming for a subtler influence, more at the level of principle than of advocacy—you know, leading the horse to water and letting it drink or not (aha! another choice for my readers to make).

JN: What are you working on now? Where do you want to take your creative practice in the future?

PD: The immediate thing I’m trying to get to amid the welter of clerical tasks I have to fulfill in getting my work out either through publication, recording, or in-person performance, is a follow-up to Sonosyntactics, entitled The Poet’s Revenge: UNselected Poetry of Paul Dutton, which will consist of poems excluded from Sonosyntactics , but that I think are worth having out there again. Next will be organizing into a new collection the print poetry I’ve written since my 1991 collection Aurealities. And I’m hoping to, along the way, get my teeth into some fiction that’s struggling to the surface from somewhere within me.

And then there’s my soundsinging, solo or in collaboration. My main band, CCMC (the initials stand for whatever you’d like), continues to play within and beyond Toronto. And I’m pursuing concert opportunities for two or three duos I’m in with instrumentalists.

Source:

Somerset, Jay and Paul Dutton. “Towards the Ineffable: A Conversation with Paul Dutton.” Musicworks 99 (2007). 30-37. <http://doyouconcur.com/articles/PaulDuttonMusicworks.pdf>

PAUL DUTTON'S MOST RECENT BOOK

Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry

Wilfred Laurier University Press

| Description from the publisher: Sonosyntactics introduces the reader to over forty-five years of Paul Dutton’s diverse and inventive poetry, ranging from lyrics, prose poems, and visual work to performance texts and scores. Perhaps best known for his acclaimed solo sound performances and his contributions to the iconic sound poetry group The Four Horsemen, Dutton is a surprising, witty, sensitive, and innovative explorer of language and of the human. This volume gathers a representative selection of his most significant and characteristic poetry together with a generous selection of uncollected new work . Sonosyntactics demonstrates Dutton’s willingness to (re)invent and stretch language and to listen for new possibilities while at the same time engaging with his perennial concerns—love, sex, music, time, thought, humour, the materiality of language, and poetry itself. |

A Little Light Love

RUSTY TALK WITH LIZ HOWARD, WINNER OF THE GRIFFIN POETRY PRIZE 2016

| | Liz Howard was born and raised in northern Ontario. She received an Honours Bachelor of Science with High Distinction from the University of Toronto. Her poetry has appeared on Canadian literary journals such as The Capilano Review, The Puritan, and Matrix Magazine. Her chapbook Skullambient was shortlisted for the 2012 bpNichol Chapbook Award. She recently completed an MFA in Creative Writing through the University of Guelph and works as a research officer in cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto. |

In my poetry I hunger to reside, if even uncomfortably, within the pyroclastic flow of my own consciousness. What can I offer to anyone? What account is most significant? How do I write about the deeply, darkly personal with rigour and beauty? How to not turn my face away?

Liz Howard: Pie has always struck me as uncanny. There is something repellent for me about the notion of cooked berries or fruit. A berry is best consumed raw, to my taste, at a temperature no greater than being warmed by direct Boreal sunlight in the afternoon hours of July 22nd, 1997. In childhood I witnessed the entombment of thousands of wild blueberries in pie crust. Pie, for me, is a fearful thing, a depravity.

Cake is a different matter. It comes from a box and your mother bakes it for you on your birthday. Cake is therefore a manifestation of filial love. Let us all eat cake. Let it be chocolate, especially.

JV: If you were a Ghostbuster who could bust ghosts using poetry, what poem would you use against a ghost?

LH: I believe I would use Fever 103° by Sylvia Plath. Its intensity, accusations and radical shifts in mood would no doubt cause the ghost to say that it realizes it hasn’t yet gotten over a prior haunting and needs time alone to reconnect with itself.

JV: Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent is very organic and very visceral. I find you're fearless in your pursuit of existential earthly answers. What do you hunger for in your poetry? What do you search out in the world of poetry?

LH: In my poetry I hunger to reside, if even uncomfortably, within the pyroclastic flow of my own consciousness. What can I offer to anyone? What account is most significant? How do I write about the deeply, darkly personal with rigour and beauty? How to not turn my face away? I hunger for moose meat and clarity. I hunger for dreams and to never awake. I hunger for the strangest phrase, for the night to continue, for my father to be alive. I hunger to express the irrepressible effects of being a creature who has born witness to and so far survived the effects of colonial late capitalism.

In the world of poetry I hunger for a feminist utopia wherein not one of us is afraid to name, say or make.

JV: ”No one occupies me like me. And no one / makes me lonelier” In terms of an independent being in a world of mass independent beings, what are your thoughts on breaking free from colonialism now, especially in literature?

LH: Talk about the tie that binds. As in double bind. As in, “I hate you, never leave me.” I was born a problem and I endeavour to remain thus. Kathy Acker wrote, “Life doesn’t exist inside of language: too bad for me.” My life is under threat inside of colonialism and so I must try and write outside it while dwelling within it and paying its bills. It is a cruel madness, unending.

JV: This is your debut collection. How does it feel for you to have your words out there? Tell me about the process of letting go of the work and your book now having a life of its own apart from you?

LH: The feeling is oddly taxidermic. As if I’ve flayed my own skin and transposed it onto a shape that vaguely resembles me, and then that is conceived into a reproducible format. I have been fortunate in that my work has been received well. I have no idea what my book is doing out there without me and this is at once exciting and mortifying.

I feel as though I never really had an opportunity to “let go” of the work. Everything happened and continues to happen so fast. I can barely keep up with my own monstrosity. A rich embarrassment.

JV: What's on the agenda for the future? Is there something you've always wanted to work with outside of literature or as in a collaboration?

LH: The future is the greatest uncanny valley. That being said I suppose I’m working on an extended account of my life and the history of Northern Ontario. I hope to work on a sound-based performance and write about indigenous dance practice. Mostly I hope to craft a life that is liveable for me and be kind to the ones who love me. Fundamentally, I hope to continue to survive.

Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent

McClelland & Stewart, 2015

| Description from the publisher: In Liz Howard’s wild, scintillating debut, the mechanisms we use to make sense of our worlds – even our direct intimate experiences of it – come under constant scrutiny and a pressure that feels like love. What Howard can accomplish with language strikes us as electric, a kind of alchemy of perception and catastrophe, fidelity and apocalypse. The waters of Northern Ontario shield country are the toxic origin and an image of potential. A subject, a woman, a consumer, a polluter; an erotic force, a confused brilliance, a very necessary form of urgency – all are loosely tethered together and made somehow to resonate with our own devotions and fears; made “to be small and dreaming parallel / to ceremony and decay.” Liz Howard is what contemporary poetry needs right now. |

EVERY HUMAN HEART IS HUMAN

I could call this

a streamlet a better

coordinate, simply

lamprey

in the trafficking

style no matter

any purple sky

or blue vapour

tender pine

became women

working the real

number is even

higher

when I was

out already

cunting in the fields for that fallow

had escaped me

in some marsh

of insufficient housing

laughing

all the time Christ thought me

a fossil

I, Minnehaha, a small LOL

fiction antecedent

to quarry a nation

I gave you this name then said

Erase it

RUSTY TALK WITH SORAYA PEERBAYE

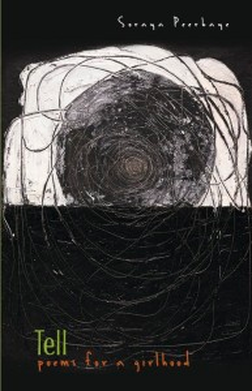

The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. [...] I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered.

Soraya Peerbaye: My desire to write about the murder of Reena Virk crystallized after the first conviction of Kelly Ellard was overturned and the second trial was set. The media had framed the case as an example of the rise in “girl violence,” as though the potential aggression of girls and women was a new phenomenon, without recognizing the social hierarchies of race, gender and beauty norms that made girls like Reena so intensely vulnerable. Then it seemed that the legal system could not believe in the guilt of a young, white girl. So the first impetus was political; I wanted to speak to the chasm between those public discourses, and the experience of so many women of colour I knew—those of us who had made such delicate transactions in girlhood to stay out of harm’s way.

As for the poetic—that was a response to the trials themselves. I think anything direct I might have wanted to say was undone by what was unknown, uncertain, denied. By the fact that the young people who testified had so few words to describe Reena herself, her struggle to survive. Even in describing themselves, what they’d done, they couldn’t speak in an embodied way of their own memories. There were salient elements that the trials couldn’t hold because they weren’t directly tied to questions of guilt or motive; yet these were the moments that the witnesses seemed to awaken, to quicken.

There was a profound sense that we, as a culture, were dredging for something, and at the same time eroding it; that the telling and re-telling was creating a crisis not only for the trials and a potential verdict, but also for the lives of these young people and Reena’s memory. Poetry felt like a way of holding these truths and lies, memories, omissions, silences, with regard for the valence of all of it.

PW: Did you look to other elegiac poems or any other works that dealt with grief for examples and guides, and if so, what were they?

SP: Carolyn Forché’s Blue Hour and her anthology Against Forgetting were early inspirations. Other collections I looked to with more intent were Marlene NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and Sachiko Murakami’s The Invisibility Exhibit. I was riveted by their sustained attention to terrible events; with the way they worked with documentation, testimony; race and gender and law; with the lack or loss or disintegration of memory and artifacts; with time. In Murakami’s work, it was also the way she carried that event in her daily life—what seemed innocuous in the ordinary world, and the way it was tainted by the trauma she was carrying.

I’m not sure how much elegy and grief were the driving questions. I didn’t know Reena; it wasn’t my grief. It was more about endurance, maybe closer to vigil. I also read Steven Ross Smith’s Fluttertongue 4: adagio for the pressured surround. It’s an annotated vigil; there’s a violence in its lyricism, in the tension and release between memory, a contemplation of the political, the act of tending to the beloved during a prolonged dying, and the quotidian. I feel the influence of that collection in the Gorge poems in Tell.

PW: Tell’s five sections seem to me to have a kind of circular motion. As a reader, I felt like I started on the outer rim, was sucked into the dense and dark centre, and then was whirled out again. How did you find the arrangement and shape of this manuscript?

SP: I was searching for that shape and energy for a long time, but really only found it in the process of revision with Beth Follett, for which I am very grateful. It needed to be released from chronology, from the sequence of events, the process of ascertaining guilt or innocence. I knew from the beginning that this wasn’t a murder mystery; if Ellard had been acquitted, it wouldn’t have changed the book significantly—the material might have been flung further apart, but still by the same physics.

I think the manuscript works through the turn and return around the same events. The narrative isn’t stable; each turn has the potential to complete a narrative but more so to disturb it—to create other currents, other pools.

Circular, yes. Coming to the verge of something and then whirling outwards. It bears repeating how many trials there were related to the case—from the trials of the young girls charged with aggravated assault, to the trial of Warren Glowatski, to the three trials of Kelly Ellard. I think of it more as a spiral; the witnesses circle around the same questions but at different points of their lives: 13, 15, 19, 21, 27...their lives are changing but tethered to the same forces and the same questions of who they were.

PW: I felt the speaker in these poems questioned racialized experiences and violence without ever expecting to come across a satisfying conclusion. Was that tension deliberate? Did you set out to create a feeling of open-endedness?

SP: Yes and no—it wasn’t so much an intent, but I did want to map it as I experienced it. At the heart of the collection is the girl I was. I had no language as a child, or even as an adolescent, for my experience of race or racism. Finding those words changed the experience and gave me a different capacity to bear it.

I admit I wish I had the assuredness of other poets, who can channel both the tenderness of who we were, and the rage, personal and communal, of our present recognition of that. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is foremost in my thoughts as I write this—the kineticism of her writing emerges from her naming of things through every kind of language that she has, lyrical, critical, activist... and the way those languages catalyze each other.

Law looked for an explicit motive and a binary delineation between the accused and the victim. My dear friend, scholar Sheila Battacharya, once commented on the Reena Virk case as an event “that has no motive but is not neutral.” It’s that I’m trying to get at; the feeling of it being charged with racism, and for that matter with cruelty towards big bodies, androgynous bodies. It’s charged and we feel it but can’t hold it. We don’t often describe the Reena Virk case as a gendered crime, in the way it enforces white feminine hegemony—but it is that, too.

PW: Similarly, although Reena’s attackers were tried for the crime, there’s a sense of another trial that involves the reader and viewers of the event, as well as all Canadians who are unknowing or who stand passively by when bullying takes place. There’s a sense of culpability that can’t quite be washed away. How did you explore the idea of trial and guilt in your writing process?

SP: I think that unlocking questions from the legal proceedings allowed me to consider, what exactly is being asked here? Who do we believe, who do we want to believe and why? One of the statements that didn’t find its place in the manuscript was a riposte by Ellard when she was first questioned by police: “This is Victoria. No one gets murdered in Victoria.” I kind of laughed when I read it—it’s such a bitchy and astute play—a comment on the mindset before the finding of Reena’s body.

I was struck in the trials by the power plays in the courtroom language; how the young witnesses tried to be more formal, in their language and tone, to regain authority over their own memories or claims of truth. The way their voices dropped, their stammering, was so often taken as an indicator of unaccountability, lying or even just dumbness. I wanted to examine the fairness of that, and at the same time undermine the brutal formality of the courtroom in the face of the witnesses’ experience, the authority of adulthood, of prosecution; to reveal what felt like a kind of vulnerability on the underside of the questions. And at the same time there were entire series of examinations and cross-examinations in relation to moonlight, tide, mud, shooting stars—and no one, neither adult nor child, is accountable to the natural world; they talk about it without seeing it.

PW: Can you talk about the difficulties of working with these source texts—the autopsy reports, the testimonies, and any other texts? Was it similar in some ways to writing a found poem?

SP: The source texts were always alive and full of potential for me. “Examination” was probably the only poem I consciously thought of as a found poem. Otherwise, I was trying to intervene more actively with the text, even when the intervention was about creating a relationship between the source, and silence, or unanswerability. There’s a process of critique that is continuous and shifting: sometimes I am questioning, but oftentimes the source unintentionally subverts or asserts itself.

But I guess that’s what a found poem does.

I’ve been thinking about the term ‘rewilding,’ and wondering if what I was responding to was a sense that the legal proceedings were domesticating a discourse around young people, violence, contempt... I turned to archaeological texts, or my conversations with Cheryl Bryce’s words as Lands Manager for the Songhee First Nations, because it reimagined the ecology of Victoria; an antidote to the domesticated way of describing the city’s beauty, the shock that such a terrible crime could have happened in a such a place, a “tea-town.” There is a desire for me to rewild the testimony, to return it to a larger ecosystem, beyond the trials and the verdicts.

PW: The book’s middle section about your own family, identity and girlhood, actually brings the reader closer to understanding and visualizing the invisible details of Reena Virk’s life. Did you hope to bring the reader into spaces that they might not usually venture?

SP: It’s good to hear that. I hesitated to write about myself; I didn’t want to suggest any equation between my experiences and Reena’s. But it became necessary to remember how hard I wanted to be seen; to have that touchstone, even if I couldn’t offer anything of Reena’s life before the night of her death.

There’s guilt for me in this section—that I’m writing this from such a privileged position. I don’t know what I hoped that the reader might feel in relation to my life, except maybe that tension; the difference between the strategies I could use and Reena’s. That I tried so hard to be a good girl, while Reena transgressed.

The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. She pissed them off, royally. Shoilee Khan, writer and director of the Bluegate Reading Series in Mississauga, told she remembered being in grade seven and poring over every newspaper article, “enthralled” at the strength of Reena’s desire and her daring. I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered.

Tell: poems for a girlhood

Pedlar Press, 2015