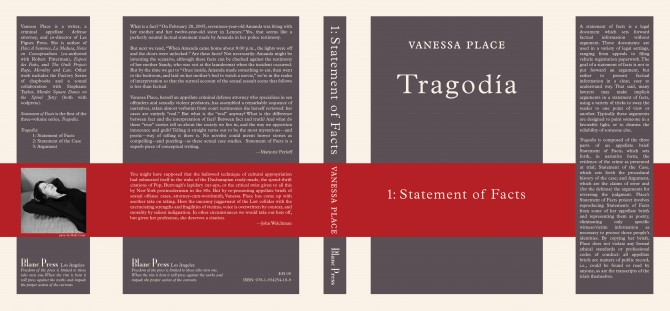

Vanessa Place Vanessa PlacePhoto by Robert Ransick Vanessa Place is a writer, a lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press. She is author of Dies: A Sentence (2006), La Medusa (Fiction Collective 2, 2008), Notes on Conceptualisms, co-authored with Robert Fitterman (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009), The Guilt Project: Rape, Morality and Law (2010), a book of conceptual poetry, Statement of Facts (éditions è®e, as Exposé des Faits), and a trilogy of conceptual work, Statement of Facts, Statement of the Case, and Argument (Blanc Press). Her Factory-type chapbook series is available via oodpress (Brazil). Place is also a regular contributor to X-tra Art Quarterly, and has lectured and performed internationally. RUSTY TALK WITH VANESSA PLACE Kathryn Mockler: How did you first come to writing? Vanessa Place: Cautiously. KM: How would you describe conceptual writing to someone unfamiliar with the genre? VP: Conceptual writing is writing that does not direct its reception. It may not be written by the purported author, it may not be read by the supposed reader, though it should be thought thoroughly through by all players. KM: How did you get interested and involved with it? VP: Robert Fitterman introduced us, and oversaw our first dates. KM: What writers would you recommended to someone aspiring to be a conceptual writer? VP: Look at Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith’s Against Expression. Read Goldsmith’s Uncreative Writing and Marjorie Perloff’s Unoriginal Genius. Pay attention to Kim Rosenfield and do not neglect the canon. KM: Do you have a piece of advice for those entering the genre? VP: Remember it’s not personal. KM: What are you working on now? VP: My Êtant Donnés. _ _A RECENT PROJECT BY VANESSA PLACE Statement of Facts, Blanc Press, 2010 _

Description from Blanc Press: A statement of facts is a legal document which sets forward factual information without argument. These documents are used in a variety of legal settings, ranging from appeals to filing vehicle registration paperwork. The goal of a statement of facts is not to put forward an argument, but rather to present factual information in a clear, easy to understand way. That said, many lawyers may make implicit arguments in a statement of facts, using a variety of tricks to sway the reader to one point of view or another. Typically these arguments are designed to paint someone in a favorable light, or to dismiss the reliability of someone else. Tragodía is composed of the three parts of an appellate brief: Statement of Facts, which sets forth, in narrative form, the evidence of the crime as presented at trial; Statement of the Case, which sets forth the procedural history of the case; and Argument, which are the claims of error and (for the defense) the arguments for reversing the judgment. Place’s Statement of Facts project involves reproducing Statements of Facts from some of her appellate briefs and representing them as poetry. “What is a fact? “On February 28, 2005, seventeen-year-old Amanda was living with her mother and her twelve-year-old sister in Lennox.” Yes, that seems like a perfectly neutral factual statement made by Amanda in her police testimony. But next we read, “When Amanda came home about 8:00 p.m., the lights were off and the doors were unlocked.” Are these facts? Not necessarily: Amanda might be inventing the scenario, although these facts can be checked against the testimony of her mother Sandy, who was out at the laundromat when the incident occurred. But by the time we get to “Once inside, Amanda made something to eat, then went to the bedroom, and laid on her mother’s bed to watch a movie,” we’re in the realm of interpretation so that the surreal account of the sexual assault scene that follows is less than factual. Vanessa Place, herself an appellate criminal defense attorney who specializes in sex offenders and sexually violent predators, has assembled a remarkable sequence of narratives, taken almost verbatim from court testimonies she herself reviewed: her cases are entirely “real.” But what is the “real” anyway? What is the difference between fact and the interpretation of fact? Between fact and truth? And what do these “true” stories tell us about the society we live in, and the way we apportion innocence and guilt? Telling it straight turns out to be the most mysterious—and poetic—way of telling it there is. No novelist could invent horror stories as compelling—and puzzling—as these actual case studies. Statement of Facts is a superb piece of conceptual writing.” —Marjorie Perloff You might have supposed that the hallowed technique of cultural appropriation had exhausted itself in the wake of the Duchampian ready-made, the spend-thrift citations of Pop, Burrough’s lapidary cut-ups, or the critical twist given to all this by New York postmodernism in the 80s. But by re-presenting appellate briefs of sexual offense cases, attorney-cum-wordsmith, Vanessa Place has come up with another take on taking. Here the uncanny juggernaut of the Law collides with the excruciating strengths and fragilities of victims, voice is overwritten by context, and morality by salient indignation. In other circumstances we would take our hats off, but given her profession, she deserves a citation. —John Welchman By repurposing legal prosecution and defense documents of violent sexual crimes verbatim, Statement of Facts takes on issues too messy to benefit from further elucidation which only grow more disturbing presented in their purest case material form. For some, what Statement of Facts brings into the public square is salacious, but Place is in effect saying: ‘I move the ball out of this arena and take it into this arena’ in order to pump up the socio political volume on this legal/moral battlefield. Her definition of injustice is sweeping. Statement of Facts does not care what the reader thinks about content and in essence, Place’s relationship to content is like Oprah Winfrey’s to money. It is straightforward, and you are free to project onto it whatever you need to. However you respond to this fierce book, it is indisputable that Statement of Facts has carved out a place for itself as a touchstone of poetic push back. As Pasadena Superior Court Judge Gilbert Alston famously quipped in his dismissal of a 1986 rape case because the victim was a prostitute: ‘A whore is a whore is a whore’--Statement of Facts counters by unflinchingly reminding us ‘a rape is a rape is a rape.’ —Kim Rosenfield |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed