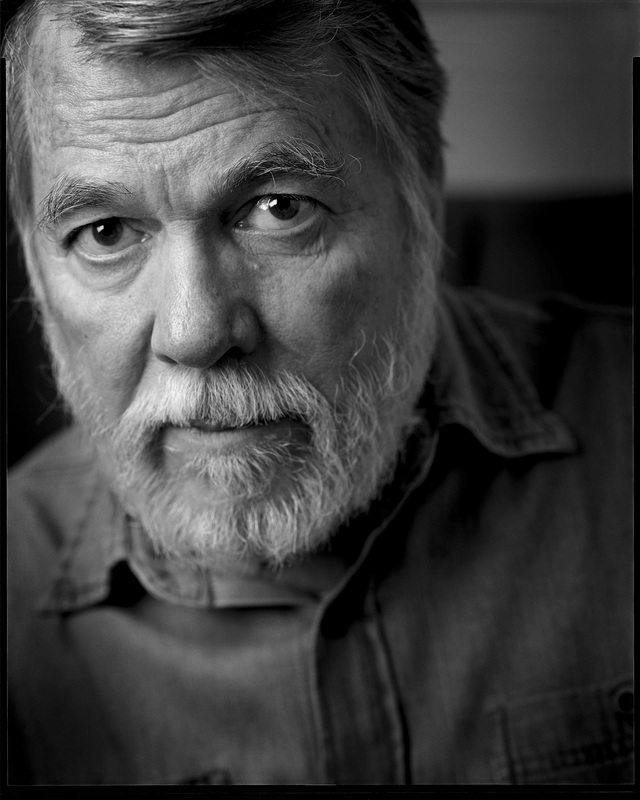

RUSTY TALK WITH PAUL DUTTON

This communication was conducted by email between John Nyman and Paul Dutton. John Nyman: At Rusty Talks we often ask writers about their first memory of writing creatively. Your career, however, has focused at least as much on your signature oral performance technique of “soundsinging” as it has on “writing” in any traditional sense, and you have said on several occasions that you see your work as “a continuum; pure music at one end of the spectrum and pure verbality at the other end” (Somerset). Considering this, what is your first memory of engaging in any creative activity, whether musical, verbal, visual, or something in between? Paul Dutton: In my preschool years, when I got pissed off about something, I’d stomp up the stairs, blistering the air with the foulest language I knew: “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Stinkers and Bums!” That, at any rate, is how I have always remembered it, but my eldest sister recently insisted, quite adamantly, that what I shouted was, “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Bums and Stinkers!” And that has made me wonder if I perhaps reconstructed, from abiding family lore, my personal memory of my oft-repeated display of pique, complete with a mental image of my miniature self pounding up the staircase. Whether the memory I hold is truly mine or borrowed from accounts heard from family members, it’s clear that, somewhere along the way, I exercised a bit of aesthetic initiative, reversing the last two terms to create a skippier cadence. JN: What would you say are the similarities and differences between your sound performance and your written work? PD: Oh shit, I don’t know . . . [3 days later (because let’s admit it: I’m writing this, not speaking it)]: Okay. I’ve thought a lot about this. First of all, my work doesn’t in fact readily divide into “sound performance and written”: there are all kinds of gradations and overlaps. As well, there are plenty of similarities and differences within those two categories, not just between them: for one thing, I write print poems in no one style but throughout a wide range, including formal, free verse, minimal, narrative, with line breaks, run-on, found poems, etc. My sound poems range through a variety of styles as well. And then there are the visual poems, which are arguably as much drawn as they are written—if typing a bunch of punctuation marks, as in my Mondriaan Boogie Woogie sequence (two of which appear in Sonosyntactics), can even be called writing. I like to refer to the whole field of visual poetry as “drawing with the alphabet.” So, we’re getting into distinctions and categorization here, which always make me feel uncomfortable. In so much of my work—and in almost everything else in the world—categories overlap or merge. Anyway, there are no consistent similarities and differences between my soundworks and poems for reading (to substitute terms for your two categories). I have linguistic and non-linguistic poems in both of those categories. I have sound poems with words and fluid syntax, and “written works” with no words (single letters or phonemes instead) and fractured syntax. A number of poems fall into both of your categories, some with performance notes, some without; and some whose written versions have shortened passages of what would be extended repetitive material that works fine in performance but would be oppressive in print. Since the late 1990s all my newly created soundworks have been totally improvised and almost exclusively nonsemantic, unlike the painstakingly worked-over poems composed for reading and recitation. I still perform repeatable repertoire works, which are likewise worked over, but I have long since stopped producing new works in that mode. One consistent feature across the various categories that can be applied to my creations is that the individual works proceed out of themselves: I begin with some generative notion—a word, phrase, image, sound, whatever—and find my way by following the poem (or fiction), sensing its direction and development rather than imposing any preset idea of where it will wind up. In a pure-sound improvisation I of course move more rapidly through the process than when I’m working over something in a repeatable form. Another consistent feature is concentration on the sonic qualities of language and of human utterance in general. This is reflected in the titles I’ve given some of my books (Sonosyntactics, Aurealities, and Right Hemisphere, Left Ear) and my two solo CDs (Mouth Pieces and Oralizations). JN: How do you convey your creative efforts to the listener/reader when you have access to only one medium or the other? PD: I’ve partially answered that already in the third and fourth paragraphs of my response to your previous question. Some of my sound poems are thoroughly worked out—what in music is sometimes referred to as “through composed,” though that typically means notating pitch, rhythm, phrasing, dynamics, and tempo, whereas I never specify pitch, rarely specify volume, and generally, both in sound poems and poems specifically for the page, leave various of those elements to be inferred, implying them by punctuation, line breaks, and distribution of the text over the page. I’ve one printed poem for which I’ve provided idiosyncratic diacritics, briefly explained; and several for which, as already stated, I’ve provided explicit performance notes. JN: You often write about numbers—not mathematical equations, but numbers as quirky and surprising participants in dramatic situations. Why this fascination with the numerical? PD: Maybe its compensation for my general innumeracy. You know, a fascination with one’s disability, or an obsession with an unrequited love. JN: Your work contains many poignant references to time, especially in relation to performance and the body. For example “Milk-Cart Roan” opens with breath breathe JN: How does the idea of time connect, or differentiate, the kinds of writing and genres of artwork you engage in? PD: Hmmm. Time. Well, my readings and my musical performances of course operate within time constraints, either very tight (“No more than five minutes, okay, Paul?”) or very loose (“Take as long as you want”). Does that qualify as a connection? Well, here’s a for-sure differentiation: improvised soundworks are created within the time it takes to perform them, but a poem (whether a sound poem or a conventional print poem) that took me months to compose can be read in a matter of minutes or even seconds. And then there’s content: an awful lot of my bookable poems deal with multiple aspects of time, either referring to or reflecting on various temporal conundrums, ambiguities, possibilities, illusions, and incongruities, among other time-related phenomena (like memory, for example). I’ve got a semantically based sound poem entitled “Time” that starts out with that word and moves through a developmental process to arrive at the word “untime”—which is another obsessive notion for me. But I’ll be damned if I can see a way to get any of that kind of content across within a nonverbal sound improvisation. JN: Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry of Paul Dutton is the newest entry in the Laurier Poetry Series, collecting some of the best poems from your nearly 50-year career with an introduction by Gary Barwin and an afterword by you. How did Sonosyntactics come about, and what did you hope to accomplish with the collection? What was it like working with Barwin (who also selected the collection’s poems)? PD: It’s an invitational series, initiated by the publisher or an independent editor, and Gary proposed it to Laurier—without my knowledge, of course, sparing me the disappointment of a possible refusal. Both Gary and I wanted it to be a collection that fully represented the multimodal character of my work and we’re both satisfied that it is. The concept of the series is to present 35 poems by any given author, which we considered unworkable at the outset, so just went our merry way but kept it within range of the more-or-less average page count in the series. I mainly left it up to Gary to choose, but twisted his arm over a few poems I felt had to be in there for one reason or another. He has either a supple arm or a high tolerance for pain, cuz he didn’t cry out too loudly. To switch the metaphor, we saw eye to eye on almost everything. JN: For me, one of the most striking parts of Sonosyntactics is “Lines on a Line of Kurt Schwitters,” a multidirectional matrix of typewriter lines riffing on Schwitters’s “Decide for yourself where the poem begins.” The collection as a whole presents us with a variety of reading challenges whose solutions we do have to “decide for ourselves”: branching paths nested in long footnotes (“Uncle Rebus Clean-Song”), extremely dense and repetitive prose (“A Little Light Love,” “Thinking”), and performance notes far longer than the “poem” they annotate (“Mercure”), to mention just a few. What role does choice play in your writing, both for you as a writer and for your intended or imagined reader? PD: A choice I make with each poem I write is to compose it either with line breaks or as run-on text—what is usually called prose poetry, a term I frankly find pointless. I myself would never designate such works as “A Little Light Love” or “Thinking” as prose. They are poems, plain and simple, and a qualifier such as “prose” is neither necessary nor helpful. Surely what makes a literary work poetry is the character of the writing, not the way the words are laid out on the page. There’s an awful lot of prose getting published that’s written with line breaks. Writing is, of course, very much a matter of making consecutive choices, either instantaneously or over the course of minutes, hours, days, even years. Yeats somewhere (in a poem, I believe) characterizes poets as staying up all night in pursuit of a single word, which is a circumstance I can relate to. Even in this little exercise, I’ve gone back and forth between alternate words or phrases, or else have revised words or passages that days later I found unsatisfactory for one reason or another. As for the reader’s part in this equation, well the first choice is, obviously, to read or not read the material at all. Then a reader can choose to read silently or aloud, to imagine or attempt a performance of poems I’ve provided descriptive notes for, to heed or ignore my line breaks, to interact creatively with the text or let the words glide past, and in the case of “Uncle Rebus Clean-Song” to read the first thread straight through or else wander off down one of the side-trails. I wish I’d not used footnotes for the various narrative branches in that little fiction (which I don’t actually consider to be a poem, by the way), because the footnote implies a secondary status. Nichol used a more satisfactory method in The Martyrology Book 5, where superscripts offer the option of turning to another section of the book in the same font size, so there’s no hierarchical implication. JN: “The Eighth Sea” stands out in Sonosyntactics, both for the range of its performative strategies (from matter-of-fact cataloguing to full-on improvisational soundsinging) and for the political force of its themes: colonial violence, environmental destruction, and the collision of settler and indigenous languages in the Great Lakes region. What do you think the creative techniques you have pioneered throughout your career can contribute to deeply political conversations such as these, both in Canada and abroad? PD: Yikes! I’ll have to leave that for others to say. I do know that my good friend John Beckwith adapted some of the devices used in “The Eighth Sea” for structuring his 2015 oratorio Wendake/Huronia, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Champlain’s arrival in Huronia. I can’t imagine how to calculate the effect such works might have in the social or political spheres, but I suspect that it’s not significant. I prefer direct activist involvement as a more effective and appropriate avenue of influence in those areas. I’m not a fan of what I call propagandart—didactic or utilitarian works—however much I might applaud and revere the causes espoused. I’m out to create, not preach. I prefer to leave any political stances implicit in the artwork, and focus my attention on the aesthetic and spiritual realms, aiming for a subtler influence, more at the level of principle than of advocacy—you know, leading the horse to water and letting it drink or not (aha! another choice for my readers to make). JN: What are you working on now? Where do you want to take your creative practice in the future? PD: The immediate thing I’m trying to get to amid the welter of clerical tasks I have to fulfill in getting my work out either through publication, recording, or in-person performance, is a follow-up to Sonosyntactics, entitled The Poet’s Revenge: UNselected Poetry of Paul Dutton, which will consist of poems excluded from Sonosyntactics , but that I think are worth having out there again. Next will be organizing into a new collection the print poetry I’ve written since my 1991 collection Aurealities. And I’m hoping to, along the way, get my teeth into some fiction that’s struggling to the surface from somewhere within me. And then there’s my soundsinging, solo or in collaboration. My main band, CCMC (the initials stand for whatever you’d like), continues to play within and beyond Toronto. And I’m pursuing concert opportunities for two or three duos I’m in with instrumentalists. Source: Somerset, Jay and Paul Dutton. “Towards the Ineffable: A Conversation with Paul Dutton.” Musicworks 99 (2007). 30-37. <http://doyouconcur.com/articles/PaulDuttonMusicworks.pdf> PAUL DUTTON'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

| Description from the publisher: Sonosyntactics introduces the reader to over forty-five years of Paul Dutton’s diverse and inventive poetry, ranging from lyrics, prose poems, and visual work to performance texts and scores. Perhaps best known for his acclaimed solo sound performances and his contributions to the iconic sound poetry group The Four Horsemen, Dutton is a surprising, witty, sensitive, and innovative explorer of language and of the human. This volume gathers a representative selection of his most significant and characteristic poetry together with a generous selection of uncollected new work . Sonosyntactics demonstrates Dutton’s willingness to (re)invent and stretch language and to listen for new possibilities while at the same time engaging with his perennial concerns—love, sex, music, time, thought, humour, the materiality of language, and poetry itself. |

A Little Light Love

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed