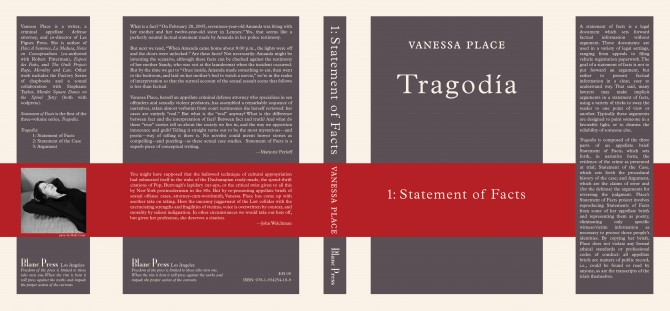

Renuka Jeyapalan _ An award winning filmmaker and graduate of the Canadian Film Centre’s Directors’ Lab, Renuka Jeyapalan is currently developing her feature film projects, How To Go To A Wedding Alone and One Lovely Night. Her short film Big Girl premiered at the 2005 Toronto International Film Festival and was awarded the ShortCuts Canada Best Short Film Award. Since then, Big Girl has screened at over thirty-five film festivals around the world—including the Berlin International Film Festival, the Tribeca Film Festival and the San Francisco International Film Festival—and was nominated for a 2007 Genie Award for Best Live-Action Short Film. In 2010, Renuka was awarded the WIFT-T Kodak New Vision Mentorship Award which included a creative mentorship with director Catherine Hardwicke (Thirteen, Twilight). Renuka has an Honours Bachelor of Science degree in Biochemistry from the University of Toronto. RUSTY TALK WITH RENUKA JEYAPALAN Kathryn Mockler: How did you first come to filmmaking? Renuka Jeyapalan: I've always loved movies and I think since I was a kid always thought of filmmaking as a "dream job", but never truly considered it as a real option for myself. I was on a path towards becoming a doctor, but during my second year at the University of Toronto, I was able to fit in a film class amongst my science courses. The course was called Contemporary Popular American Film, and I remember listening to the professor analyze the opening wedding sequence in The Godfather and that was it, I was hooked. That class really cracked open the form and craft of filmmaking for me, and I remember thinking, "I can do that!". And while I did finish my degree in Biochemistry, from that moment on in my heart and mind, I was committed to becoming a filmmaker. KM: What keeps you going as a writer/filmmaker? RJ: I think the hardest thing is figuring out your passion and what you want to do career-wise. But once you know, pursuing anything else is just inconceivable. And that's how I feel about filmmaking. When I'm making, watching or even talking about movies, I'm exactly the person that I want to be. I'm exactly myself. To give up is just not an option. And while filmmaking is a very difficult path, if that is your true passion, I don't think you really have any other choice than to pursue it with everything you've got. KM: What do you find the most difficult thing about writing scripts and the best thing about writing scripts? RJ: Everything about writing scripts is difficult! The whole thing. I once heard a radio interview with the author Philip Roth and he perfectly articulated why writing is so hard. He said that writing is the most difficult thing to do because it's lonely, painful and no one can help you—only you can tell the story, and you basically have to drag it out of you. And even though you may have written before, when you start a new story, you have never told THAT story before so it always feels like you are starting from nothing, over and over again. No matter how many screenplays, books, short stories, poems or articles you have written, you always feel like a novice. For me, the best thing about writing is that you get to express yourself under the guise of a story. That you have the power to say something meaningful, convey an idea or impart an emotion to an audience. Most of the time, you struggle with how to do this elegantly and with craft, but when it works, it's a great feeling. KM: When writing scripts what is the revision process like for you? RJ: Once I finish a draft, I put it aside for a while. I get notes from my producers, friends who I trust. and I also make my own notes about what needs work. When I feel like I have enough distance away from it, I'll start a page one re-write, only using the original draft as a guide. I aim to re-write the entire script within 10 days, with each day containing certain goal markers. For a feature screenplay, for example, on the first of the 10 days, I'll re-write the first 10 pages or the "ordinary world" of the protagonist. And on the second day, I'll re-write the next 15 pages, including the inciting incident up to the end of Act I and so on. I find that this process lets me not only incorporate new changes, but to free myself from getting too attached to scenes in the original draft. This process seems to facilitate my writing to feel more organic and fresh each time I work on a new draft. KM: What writers or filmmakers would you recommend to new screenwriters? RJ: I don't know if there are any specific writers or filmmakers that I would recommend, but I always find listening to the first person stories of filmmakers and how they wrote or made their own films to be interesting and helpful. I find that books (eg. My First Movie), DVD commentaries, podcasts (KCRW's The Treatment, The Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith) which interview the actual filmmakers on their process can be quite inspiring. KM: A piece of advice for new writers and filmmakers? RJ: Stay passionate, stay true to yourself and your vision, and above all don't give up! KM: Your funniest film/writing moment. RJ: I tend to write in coffee shops most of the time, and I remember writing at my local café one Saturday afternoon on College Street a couple years ago. It just so happened that it was during the World Cup and this café was packed with enthusiastic Portuguese soccer fans watching an important match. At one point, an old man came up to me and with this offended expression and asked me, "How can you work here?!?" And it was only at that moment, that I realized I didn't even notice the commotion around me. All these fans were screaming and cheering and glued to this big important game and there I was…so focused on my writing that I was clueless to it all. KM: What are you working on now? RJ: I'm currently living in Los Angeles in order to focus on writing and to get inspired. But I have a feature film called How to go to a Wedding Alone that is in development with the Toronto-based production company Gearshift Films and Telefilm Canada. And I've just finished a new feature screenplay and a short film script that I'm looking to make.  A SHORT FILM BY RENUKA JEYAPALAN Big Girl, short film Produced by The Canadian Film Centre & NBC-Universal, 2005 Synopsis A bittersweet battle of wills develops between nine-year-old Josephine and her mother's new boyfriend in this poignant tale of modern family politics. Screenings Screened at 25 festivals worldwide including the Berlin International Film Festival, the Tribeca Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. Awards 2007 Genie Nominee - Best Live Action Short Drama 2006 ACTRA Award for Outstanding Performance – Female (Samantha Weinstein Best Short Film - 2005 Toronto International Film Festival _  David HIckey _ David Hickey grew up on Prince Edward Island, in western Labrador, and along the north shore of Quebec. A past recipient of the Milton Acorn Prize and the Ralph Gustafson Prize, his work has appeared in magazines and journals across Canada and the United States. David is an avid runner and back yard astronomer, and he lives in London, Ontario. David Hickey has recently published a children’s book, A Very Small Something. See the trailer for A Very Small Something and listen to the audio book here. RUSTY TALK WITH DAVID HICKEY Elan Paulson: You’ve recently published a children’s book after two poetry collections. What inspired you to write this book, and in what ways do you find writing stories for children different from (or similar to) writing poetry? David Hickey: Since writing poetry is such a solitary pursuit, the opportunity to work with an illustrator definitely held some appeal for me. If there's a difference between the two I'd say it lies in that collaborative process, where you trust someone else to pick up where you left off and to imagine the world of the story. EP: You define poetry writing as a “solitary” pursuit. How else would you describe your writing process? DH: Uneventful. I write very slowly and often take in excess of a year to complete a poem. A year, in a very on-and-off sort of way, that is. My writing sessions are intermittent and typically consist of a lot of trial and error. Mostly I'm just trying to bring whatever I'm writing to comfortable state of completion, but I've learned that requires some patience. There's just no rushing poetry. Each poem takes its own sweet time deciding how it wants to be. EP: How does revision figure into your process? DH: Revision and writing are one and the same for me. I write a line, I change it, I write another, I change that one too. I don't think in drafts, but rather in terms of how long I've spent with a given line, stanza, beginning or ending. When I find I can't possibly do anything more with it, I either toss it out or consider it done. For every poem that I've published, I'm sure there's at least two others lining the drawers of my desk. EP: What is the best thing about being a writer, and what is the worst thing? DH: The best part is the actual writing itself. I'm quite content to sit and stare at a few lines on a computer screen for hours on end. I've been doing it for years. I'm sure there's something wrong with me. In my mid-twenties, though, I was putting in what felt like monumental efforts, but my writing still wasn't going anywhere. Meanwhile my friends were getting jobs and buying houses and settling down and doing those things that adults do. I believe at this point I was saving up for a timbit. In any case, writing has since provided me with a different kind of abundance. That's the best and worst part of it. I wouldn't have it any other way. EP: This quiet (but abundant) relationship that you have with your work must change when readers encounter you and your writing. What is your funniest literary moment, if you have one? DH: Somebody puked at the launch of my first book. Then a stripper-mobile drove by. All in all it was an interesting evening. EP: What advice would you give to new writers (aside from how to deal with book launch surprises)? DH: As is the case with all trades, writing begins with an apprenticeship, the length of which varies from person to person. But how long you take to develop really doesn't matter at all. What does matter is that you find a mentor you can work with and whose feedback you're willing to trust. And that person doesn't have to be someone famous or wildly talented or anything ridiculous like that--just an insightful, empathetic reader who isn't afraid to mark up your work. The good news is that such mentors aren't very hard to find. As the saying goes, when the student is ready, the teacher appears.  _DAVID HICKEY’S MOST RECENT BOOK A Very Small Something, Biblioasis, 2011 Description from Biblioasis : Olive Bezzlebee might live by the world's biggest bubble gum factory, but she can't blow a single bubble. Not one! Setting out to solve the mystery of her missing bubbles, Olive travels to the edges of her imagination, where a very small something is waiting to happen. And a miraculous adventure awaits. With lush illustrations by Alexander Griggs-Burr, David Hickey's tale of enchantment and belonging is sure to uplift aspiring bubble blowers of all ages. Praise for A Very Small Something "I like this book mainly because it’s about gum, and gum is one of my favourite snacks ... My favourite kind of gum flavour is raspberry. I don’t know how to blow bubbles yet, but my sister can. She’s nine. In the back of the book, there is a guide to blowing bubbles (it’s pretty funny actually). There are 10 easy steps. I’m going to follow it – but hopefully I don’t get lifted up to the clouds!" - Myles, aged 7, Papertrails Family Book Blog  Vanessa Place Vanessa PlacePhoto by Robert Ransick Vanessa Place is a writer, a lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press. She is author of Dies: A Sentence (2006), La Medusa (Fiction Collective 2, 2008), Notes on Conceptualisms, co-authored with Robert Fitterman (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009), The Guilt Project: Rape, Morality and Law (2010), a book of conceptual poetry, Statement of Facts (éditions è®e, as Exposé des Faits), and a trilogy of conceptual work, Statement of Facts, Statement of the Case, and Argument (Blanc Press). Her Factory-type chapbook series is available via oodpress (Brazil). Place is also a regular contributor to X-tra Art Quarterly, and has lectured and performed internationally. RUSTY TALK WITH VANESSA PLACE Kathryn Mockler: How did you first come to writing? Vanessa Place: Cautiously. KM: How would you describe conceptual writing to someone unfamiliar with the genre? VP: Conceptual writing is writing that does not direct its reception. It may not be written by the purported author, it may not be read by the supposed reader, though it should be thought thoroughly through by all players. KM: How did you get interested and involved with it? VP: Robert Fitterman introduced us, and oversaw our first dates. KM: What writers would you recommended to someone aspiring to be a conceptual writer? VP: Look at Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith’s Against Expression. Read Goldsmith’s Uncreative Writing and Marjorie Perloff’s Unoriginal Genius. Pay attention to Kim Rosenfield and do not neglect the canon. KM: Do you have a piece of advice for those entering the genre? VP: Remember it’s not personal. KM: What are you working on now? VP: My Êtant Donnés. _ _A RECENT PROJECT BY VANESSA PLACE Statement of Facts, Blanc Press, 2010 _

Description from Blanc Press: A statement of facts is a legal document which sets forward factual information without argument. These documents are used in a variety of legal settings, ranging from appeals to filing vehicle registration paperwork. The goal of a statement of facts is not to put forward an argument, but rather to present factual information in a clear, easy to understand way. That said, many lawyers may make implicit arguments in a statement of facts, using a variety of tricks to sway the reader to one point of view or another. Typically these arguments are designed to paint someone in a favorable light, or to dismiss the reliability of someone else. Tragodía is composed of the three parts of an appellate brief: Statement of Facts, which sets forth, in narrative form, the evidence of the crime as presented at trial; Statement of the Case, which sets forth the procedural history of the case; and Argument, which are the claims of error and (for the defense) the arguments for reversing the judgment. Place’s Statement of Facts project involves reproducing Statements of Facts from some of her appellate briefs and representing them as poetry. “What is a fact? “On February 28, 2005, seventeen-year-old Amanda was living with her mother and her twelve-year-old sister in Lennox.” Yes, that seems like a perfectly neutral factual statement made by Amanda in her police testimony. But next we read, “When Amanda came home about 8:00 p.m., the lights were off and the doors were unlocked.” Are these facts? Not necessarily: Amanda might be inventing the scenario, although these facts can be checked against the testimony of her mother Sandy, who was out at the laundromat when the incident occurred. But by the time we get to “Once inside, Amanda made something to eat, then went to the bedroom, and laid on her mother’s bed to watch a movie,” we’re in the realm of interpretation so that the surreal account of the sexual assault scene that follows is less than factual. Vanessa Place, herself an appellate criminal defense attorney who specializes in sex offenders and sexually violent predators, has assembled a remarkable sequence of narratives, taken almost verbatim from court testimonies she herself reviewed: her cases are entirely “real.” But what is the “real” anyway? What is the difference between fact and the interpretation of fact? Between fact and truth? And what do these “true” stories tell us about the society we live in, and the way we apportion innocence and guilt? Telling it straight turns out to be the most mysterious—and poetic—way of telling it there is. No novelist could invent horror stories as compelling—and puzzling—as these actual case studies. Statement of Facts is a superb piece of conceptual writing.” —Marjorie Perloff You might have supposed that the hallowed technique of cultural appropriation had exhausted itself in the wake of the Duchampian ready-made, the spend-thrift citations of Pop, Burrough’s lapidary cut-ups, or the critical twist given to all this by New York postmodernism in the 80s. But by re-presenting appellate briefs of sexual offense cases, attorney-cum-wordsmith, Vanessa Place has come up with another take on taking. Here the uncanny juggernaut of the Law collides with the excruciating strengths and fragilities of victims, voice is overwritten by context, and morality by salient indignation. In other circumstances we would take our hats off, but given her profession, she deserves a citation. —John Welchman By repurposing legal prosecution and defense documents of violent sexual crimes verbatim, Statement of Facts takes on issues too messy to benefit from further elucidation which only grow more disturbing presented in their purest case material form. For some, what Statement of Facts brings into the public square is salacious, but Place is in effect saying: ‘I move the ball out of this arena and take it into this arena’ in order to pump up the socio political volume on this legal/moral battlefield. Her definition of injustice is sweeping. Statement of Facts does not care what the reader thinks about content and in essence, Place’s relationship to content is like Oprah Winfrey’s to money. It is straightforward, and you are free to project onto it whatever you need to. However you respond to this fierce book, it is indisputable that Statement of Facts has carved out a place for itself as a touchstone of poetic push back. As Pasadena Superior Court Judge Gilbert Alston famously quipped in his dismissal of a 1986 rape case because the victim was a prostitute: ‘A whore is a whore is a whore’--Statement of Facts counters by unflinchingly reminding us ‘a rape is a rape is a rape.’ —Kim Rosenfield  Sheila Heti Sheila Heti lives in Toronto. She works as Interviews Editor at The Believer and is the author of five books: the short story collection, The Middle Stories (McSweeney’s Books); the novel, Ticknor (Farrar, Straus and Giroux); How Should a Person Be? (Anansi) which is forthcoming in the U.S. from Henry Holt in the summer of 2012; an illustrated book for children, We Need a Horse (McSweeney's McMullins) featuring paintings by Clare Rojas; and a book of conversational philosophy with Misha Glouberman called The Chairs Are Where the People Go (Faber and Faber). Her work has been translated into German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Vietnamese and Serbian. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, n+1, McSweeney’s, Brick, Geist, Maisonneuve, Bookforum, The Guardian, and other places. She studied playwriting at the National Theatre School in Montreal before attending the University of Toronto to study art history and philosophy. RUSTY TALK WITH SHEILA HETI Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Sheila Heti: I don't have a first memory of writing. Or reading. Or speaking! Or hearing words. KM: What keeps your going as a writer or why do you write? SH: Because not much else makes time feel so bottomless. KM: How would you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into your process? SH: I write it first, then I revise it. Sometimes I revise it right then and there, and sometimes I wait a few weeks, months or years. It depends on the piece and how much in a hurry I am. Sometimes I don't know where I want to go with it. Then I leave it alone. There's always something to work on. I used to only work on one thing at a time, but I like having many things to work on, depending on where my mind wants to be. Now I can always be working. I don't have to be in the mood or any particular mood because if you have ten things on the go, at least one of them will be what you're in the mood for. KM: What influences your writing the most? SH: The time I'm at in my life. KM: What authors or books would you recommended to someone aspiring to be an writer? SH: I would mostly just recommend not reading a book to the end if you're not enjoying it. Forget about how it turns out and go find a book you actually like. I can't believe how people waste time this way, finishing books they're not enjoying. The book doesn't care. God doesn't care. Where does this imperative come from to finish a book one has started? Move on! KM: What is the best thing about being a writer and what is the worst thing? SH: The best thing is doing what you want to do with your life (if that is what you want to do--write) and there is no worst thing. Well, maybe the worst thing is that you don't get to mature in a steady way. It's really lumpy. It's sort of dependent on finishing books. Sometimes if a book takes a long time to finish, like you start it when you're 25 and finished when you're 35, then when you turn 35, you feel more like you're 26. It's hard to believe you're actually 35.  A RECENT BOOK BY SHEILA HETI How Should a Person Be?, House of Anansi Press, 2010 Description from House of Anansi From the internationally acclaimed author of The Middle Stories and Ticknor comes a bold interrogation into the possibility of a beautiful life. How Should a Person Be? is a novel of many identities: an autobiography of the mind, a postmodern self-help book, and a fictionalized portrait of the artist as a young woman -- of two such artists, in fact. For reasons multiple and mysterious, Sheila finds herself in a quandary of self-doubt, questioning how a person should be in the world. Inspired by her friend Margaux, a painter, and her seemingly untortured ability to live and create, Sheila casts Margaux as material, embarking on a series of recordings in which nothing is too personal, too ugly, or too banal to be turned into art. Along the way, Sheila confronts a cast of painters who are equally blocked in an age in which the blow job is the ultimate art form. She begins questioning her desire to be Important, her quest to be both a leader and a pupil, and her unwillingness to sacrifice herself. Searching, uncompromising and yet mordantly funny, How Should a Person Be? is a brilliant portrait of art-making and friendship from the psychic underground of Canada's most fiercely original writer. |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed