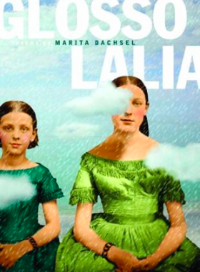

Marita Dachsel Marita DachselPhoto by Nancy Lee Marita Dachsel is the author of Glossolalia, Eliza Roxcy Snow, and All Things Said & Done. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and the ReLit Prize and has appeared in many literary journals and anthologies, including Best Canadian Poetry in English, 2011. Her play Initiation Trilogy was produced by Electric Company Theatre, was featured at the 2012 Vancouver International Writers Fest, and was nominated for the Jessie Richardson Award for Outstanding New Script. She is the 2013/2014 Artist in Residence at UVic’s Centre for Studies in Religion and Society. RUSTY TALK WITH MARITA DACHSEL Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Marita Dachsel: My mother was an elementary school teacher, and grade one was her favourite to teach partially because she got to teach kids to read and write creatively. She did a great job instilling the importance of both in me, and I know I was writing creatively thanks to her long before my first true memory. When I was around five I wrote and illustrated a collection of stories about horses called…wait for it…Horse Stories. I remember spending longer on the illustrations than the stories, and I think the illustrations came first. My parents’ living room is very gothic—red carpet, red velvet curtains, dark beams, huge heavy-glassed lights that look medieval in inspiration, a fireplace, and a menagerie of taxidermied animals and birds along one wall. But it’s the room that gets the most natural light. I remember writing one of the stories on the carpet, the sun warming my body, crayons beside me, the television on as it always was (I can’t remember the show, but Dukes of Hazard is my default childhood memory show). I was so proud of my work. I still have it. KM: How did you become a writer? MD: I always wrote. When I was in elementary school one of my goals was to be a writer when I grew up (along with fire fighter and architect, so take that for what it’s worth), and while I continued to write as I got older, it didn’t really seem like something that could be real. Then I went to college with a vague idea that I might become and English professor. There I took my first creative writing class, amazed that this was possible. I loved it. My first published poem I wrote in that class. Then I learned you could do a degree in it at UBC, so I transferred and ended up doing both my BFA and MFA there. Despite this, being a writer feels both like something that I just happened to become and something that I’ve always been. KM: What writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now? MD: Just before I took that very first creative writing class, I was in a John Steinbeck and John Irving phase. Then I discovered Canadian writers and women writers. Reading Canlit felt revolutionary. Margaret Atwood, Barbara Gowdy, Carol Shields. Anything and everything in my Canlit anthology seemed to be a springboard. Now, I don’t have enough time to read everything I want to read. So many novels, poetry collections, essays, short stories, memoirs I want to read. Right now, I’m reading Brenda Shaughnessy’s Our Andromeda, Steven Price’s Omens in the Year of the Ox, Amanda Leduc’s The Miracles of Ordinary Men, Ann the Word: The Story of Ann Lee, and what feels like a million various poems and anthologies for the poetry class I’m teaching on poetic forms this fall. I’ve been itching to start Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, but I’m going to wait for the right weekend to devour it. KM: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process? MD: My process for poetry varies a lot depending on the poem, what was its initial impulse, where it came from. I scribble lines in a notebook, return days, months later and build off a line or an image. Then cut, slash, and rebuild. With the poems in Glossolalia, so much was dependant on finding the right voice and shape. I’d research, make notes, write a draft. If the voice wasn’t right, I’d move on to the next wife. But if I felt like it was close, I’d start shaping the poem, writing more and more, then hack it to pieces, rewrite, hack, rewrite until it all sounded and looked right. Then I’d come back to it in a year or two. If it still felt right, great. If not, back to the beginning of the processes. KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one? MD: When my eldest was a baby, I read him Oliver Jeffer’s Lost and Found many times a day. It was a family favourite and when I got to the part where [spoiler!] the penguin and the boy are reunited, I would hug my son and say “A big hug for the penguin, a big hug for the boy, a big hug for you.” One day when he was about 18 months, he was “reading” the book by himself on the floor of our living room. I spied him from the kitchen. He turned to the hugging page and he hugged the book. It still makes me a little misty remembering that moment. KM: Your second poetry collection Glossolalia, is a series of monologues spoken by the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith. How did you come to the premise of this book and what drew you to the subject matter? MD: I’ve always been interested in fringe religions, and a few years ago the FLDS in Bountiful, BC was in the news. I was curious about their tenet of polygamy and discovered that it was first introduced into the Mormon Church (of which the FLDS are a breakaway sect) by their founder Joseph Smith way back in the 1840s. I wondered about the women, how they must have reacted when faced with a concept so alien to the society in which they lived, to the culture in which they were raised. I wondered how I would have reacted. I love research and can get obsessed about a subject quite easily. I found two great biographies on Smith’s wives: In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith by Todd Compton and Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith by Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery. I started reading them, responding with poems. The material is very rich—sex, religion, power, gossip, motherhood, sisterhood, jealousy. Juicy stuff. KM: You’ve managed to give each wife her own voice and an impression of her character sometimes with just a few words or a detail. An example of this are the final lines of Emma Hale Smith’s monologue: “What I know: not all eggshells are fragile. / Not all twigs snap.” This tells us so much about her and cycles back to the first line which I understand is an actual quote from Emma Hale Smith: “I did not ask for this life but accept it as my calling.” While this is a fictionalized account of Joseph Smith’s wives, how did your research come into play in terms of how you developed the voice of each wife and how you shaped the narrative of the collection? MD: I devoured the biographies and once I realized that I wanted to write a poem for each wife, that this was going to be a book-length project instead of just a few poems, I knew that I needed to get them right. They needed to be distinct, and that would be hard as they were all had similar backgrounds, lived at the same time, in the same town, shared the same faith and husband. But of course, they were all very different from each other, and I hoped to capture that. For some polygamy was something they embraced, others railed against it, and for others it was barely mentioned. The narrative was organic; I never plotted out what moments I wanted to write about. At one point I read a book about Joseph Smith’s death mask. The mask never made it into the collection, but his death was there, from a few angles. I’d read about the woman, make notes, try to hear her voice, write a draft, repeat as necessary. The first draft of the first poem I wrote for Glossolalia was Emma’s, but it took six years of rewriting her to get it right. KM: Each poem in Glossolalia takes on a different shape and form. What informed your choices about typography, line breaks, stanza breaks, etc.? MD: I believe form and content are intertwined, that they inform each other. Ultimately, it was simply a lot of rewriting, lots of playing on the page, reading aloud, and rewriting some more until it sounded and looked right. KM: In many ways, the book is more about the diverse and complicated relationships that exist between women than about the Mormon religion, but has there been any response from the Mormon community to your book and/or did you have any concerns around this? MD: There hasn’t been any direct response from the Mormon community, but I also haven’t searched it out yet, partly because I am a little scared to. I’m not Mormon, I did write about women in a community I don’t belong to, have no ties to. I am a little concerned at being called out for appropriation or being insensitive. Many of the wives have hundreds of progeny. What if there is an irate great-great-granddaughter? I shouldn’t be afraid (it’s poetry!), but part of me is nervous. I’d hate to have that kind of conflict. That said, I spoke with two ex-Mormons who came to my readings, one in Edmonton, one in Victoria. The man in Edmonton told me that I “got it right.” The woman in Victoria said that she was thankful for how respectful I treated the subject and that she’s planning on passing my book along to some in her family, many of whom are still Mormon. Those conversations buoyed me. KM: What are you working on next? MD: I’ve been working on some essays and poems that may or may not become a collection, but my big new project is a series of monologues from the points of view of self-appointed messiahs, some real, some fabricated. I’m a slow writer, but thanks to the good folks at the Centre for Studies in Religion and Society at UVic who made me this year’s Artist-in-Residence, I have space and time to create throughout this academic year. I’m very excited to see where they take me.  MARITA DACHSEL'S MOST RECENT POETRY BOOK Glossolalia, Anvil Press, 2013 Description from Publisher Glossolalia is an unflinching exploration of sisterhood, motherhood, and sexuality as told in a series of poetic monologues spoken by the thirty-four polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Marita Dachsel’s second full-length collection, the self-avowed agnostic feminist uses mid-nineteenth century Mormon America as a microcosm for the universal emotions of love, jealousy, loneliness, pride, despair, and passion. Glossolalia is an extraordinary, often funny, and deeply human examination of what it means to be a wife and a woman through the lens of religion and history.  Chelsea McMullan Chelsea McMullan A Canadian filmmaker and artist, CHELSEA MCMULLAN’S films have premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and have been screened on the international festival circuit. Effortlessly moving between documentary and fiction, her work has been described as ‘keenly observed, elegant, and profound,’ solidifying her reputation as ‘talent to watch.’ Chelsea’s award-winning shorts have been featured on NOWNESS, DAZED DIGITIAL, VICE and in VOGUE ITALIA. In 2010, her series of live portraits, Chaine, created in collaboration with Russian photographer Margo Ovcheranko, premiered at the New York Photography Festival. Chelsea has been an artist in residency at the prominent Italian creative think tank, FABRICA, where she made the Genie award nominated film Derailments. She's recently completed her first feature length film, a documentary-musical about transgendered musician Rae Spoon entitled My Prairie Home, marking her third collaboration with the National Film Board of Canada. McMullan is a member of the artist co-operative What Matters Most, a group of culture-makers with representation based out of Los Angeles. RUSTY TALK WITH CHELSEA MCMULLAN Sarah Galea-Davis: How did you first get into filmmaking? Chelsea McMullan: I don't think I've found a way to say this yet that doesn't set off my precocious detector, but I wanted to make films from a young age. There's no great story or anything, just a progression from my parents' camcorder to studying film at York University in Toronto straight out of high school. Part of me wishes I'd came to film later because I think it would have been great to study something like philosophy or psychology first. At the same time though, I still work with the same people I met in my undergrad. SGD: Was there a writer or filmmaker that had a big impact on you? CM: On a personal level Jennifer Baichwal has been hugely influential. I interned with her and her husband Nick de Pencier right out of film school and despite being a thoroughly wretched production coordinator/researcher, they've both been so patient and generous with me over the years. I was occupying a corner of their office rent-free for like four years. I used to sleep on their couch, in the editing suite, when I was up late writing a grant. Also they are fucking awesome filmmakers, and over the years I've been able to watch their process and learn from them, while deeply engaging with pragmatic, ethical, and philosophical issues around the films I'm making. My absolute favourite filmmaker is Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Hands down, end of discussion, to a very obsessive extent. A few years back in Berlin, I bought a book, which is comprised of a still image of every frame in Berlin Alexander Platz. It's like 50 lbs, and my baggage was obscenely overweight, but it was totally worth it. I would say it's one of my most cherished possessions. Actually, the mayor of the town I grew up in was his cousin. I asked him about it once, and he told me a wild story about spending time with Rainer. I think it was supposed to be a cautionary tale. SGD: What is your favourite part of the filmmaking process? CM: I find that I'm sort of anxiety ridden through the whole process. Though if I have to choose my favorite part, it is probably watching rushes. There is still so much promise and nothing has gone wrong yet, but you’re past the soul-destroying production hump. It's a nice purgatorial state before you have to pull your baby apart and sacrifice it to keep the gods happy. SGD: What is the best filmmaking advice you've received? CM: Once something really bad had happened to the main subject of one of my films. His wife had a horrible brain aneurism and was in the hospital. I was young, so I thought the film was over and was ready to throw in the towel. I phoned Jennifer and told her about the situation, and she was like "Chelsea, this is your job. This is what being a documentary filmmaker is." I've never forgotten that. The times it feels most difficult and awkward to shoot are the times when usually it is most important because those are the moments of people's lives that we don't really share enough. Also more often than not people want their tragedies documented. They want to feel like people are experiencing with them, that there's value in their loss. SGD: Your work spans the genres of documentary and experimental filmmaking. Do you approach the writing/creation process differently when it comes to your non-fiction work? CM: I never set out to make documentary, fiction, or experimental films. A subject just crosses my path, and I follow it down the rabbit hole. I also feel like my work usually sits in some space of hybridity. I've never sought out a subject for a film, it always comes to me, and then I just try to tell the story in the best way I know how. The genre, the length, the style for me are all dictated by the subject matter. SGD: Tell us about your current documentary that is being released in November? CM: The NFB hired an actual writer to explain it in a concise and inviting fashion. Know that it is a passion project that Rae and I have been working on for the past four years or so together. Rae is a good friend and this was an important project for me. SYNOPSIS: MY PRAIRIE HOME In Chelsea McMullan’s documentary-musical, My Prairie Home, indie singer Rae Spoon takes us on a playful, meditative, and at times melancholic journey. Set against majestic images of the infinite expanses of the Canadian prairies, Spoon sweetly croons us through their queer and musical coming of age. Interviews, performances, and music sequences reveal Spoon’s inspiring process of building a life of their own, as a trans person and as a musician. TRAILER: |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed