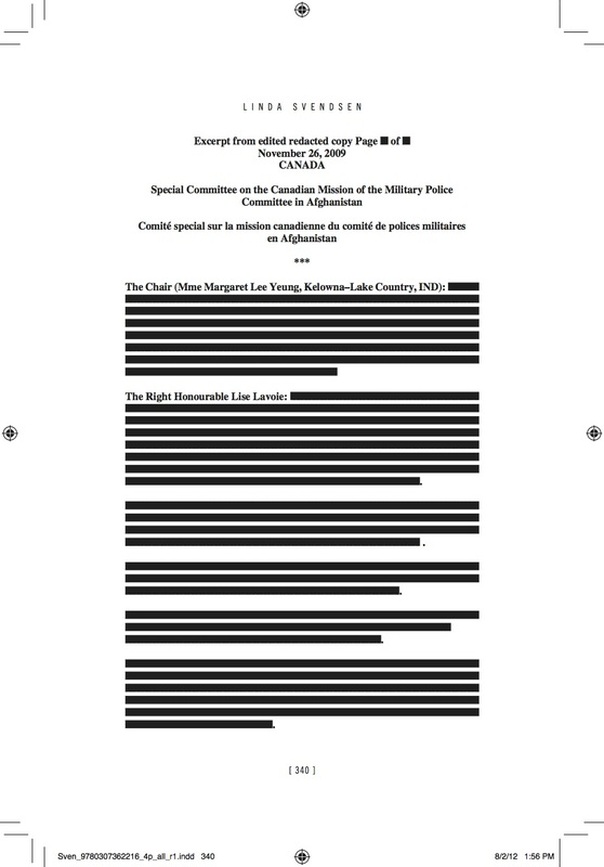

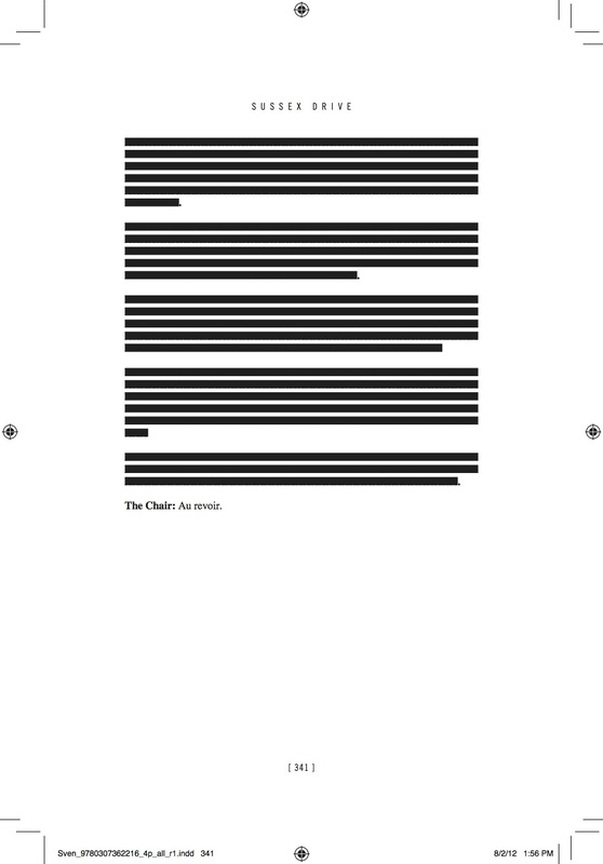

Roddy Doyle Photo by Mark Nixon Roddy Doyle was born in 1958. His work includes The Commitments, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha (Booker Prize, 1993), The Woman Who Walked Into Doors, A Star Called Henry, and Bullfighting. His latest book is Two Pints (2012). A new novel, The Guts, will be published in August, in Ireland and the UK, and early 2014 in the USA. He divides his time between Dublin and confusion. RUSTY TALK WITH RODDY DOYLE Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Roddy Doyle: I was about ten, I think, and my teacher, Mr. Kennedy, told the class to write something about a rainy day. This was Ireland, remember, so deep research wasn’t necessary. There were fifty-four boys in the class, and it was the first time we’d been told to write, or compose, anything—to make it up. I wrote about boredom. Mr. Kennedy looked over my shoulder, then read it to the class. KM: Why did you become a writer? RD: I loved reading. I loved football—soccer—but was a hopeless player. I loved music but hadn’t the patience or ability to learn an instrument. But I was literate, so writing seemed like an easy option. I forced myself into the habit, the routine. KM: What is the best writing advice that you’ve gotten that you actually use? RD: Treat it as a job; don’t expect magic. KM: How do you approach revision? RD: If by ‘revision’ you mean editing, I love it. So I approach it with a full heart and a red ballpoint. I tend to, deliberately, write too much. Editing is often a case of paring back. I’m fascinated, and sometimes worried, about how the deletion or addition of a word can alter meaning, tone, everything. When I’m editing, I put all other work aside and concentrate only on the pages I’m editing. I don’t play music, and I often lose track of time. KM: Your books often come out within a few years of each other. Do you work on multiple projects at the same time or stick to one project until it’s complete? Do you have difficultly switching from one genre to the next—particularly from adult fiction to children’s literature? RD: I work on different projects at the same time; I divide my working day, about 9am to 6pm, into chunks. As long as the projects are very different, they don’t tend to infect each other. I play a different type of music for each project. I could, I suppose, change shirts too, but that might be going too far. So, I can work for several hours on a novel, save it, hang out the washing, make a cup of coffee, change the Rolling Stones for Steve Reich, and get working on a treatment for a possible TV series or a book for children. KM: What writers were influential when you first started writing? Who are you reading now? RD: I think Flann O’Brien was important, particularly the Dublin dialogue in At Swim-Two-Birds. E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime was important—the simplicity of the language. I’ve just finished George Saunders’ collection, Tenth of December; I think it’s magnificent. I’m reading a collection of J.G. Ballard interviews, called Extreme Metaphors. It’s great. KM: Given the amount of books that you’ve written, it seems impossible to imagine, but do you ever get writer’s block? And if you do, how do you overcome it? RD: No—never. KM: Do you ever abandon projects? If so, how do you know when it’s time to move on? RD: I’ve never abandoned, but I’ve parked projects for a while, stayed away from them until I was ready to look at them with that mixture of calm and excitement that I need if I’m going to work. Because I work on several things during the day, if one project isn’t going well, I can focus on another. KM: We often talk about the difficulty of rejection for writers but what about the problems that success can bring? After you won the Booker Prize in 1993 for Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, for instance, what was it like sitting back down at the writing desk? RD: Success, however we measure it, is much nicer than rejection. But rejection can be like fuel to an almost empty engine. Rejection is a cousin of determination, and it’s part of the job. Success is too, if you’re lucky. The trick is, I think, to ignore it when you’re at your desk. I never let myself think that, just because I’ve won a prize, I’m not capable of writing shit. After winning the Booker, I couldn’t wait to get back to work. I love the work. KM: You posted your latest work Two Pints, which was just published in its entirety in November, as a serial on Facebook over the last year and half. Why did you decide to do this and what was the process like for you? Did the process have any affect on the end product? In other words, did the reader comments influence revisions? Would you do it again with another project? RD: I wrote the Two Pints pieces for fun. Someone suggested they’d make a good book, so—grand. It’s an accidental book, and still fun. I still write the Two Pints pieces, when the mood hits me and I have time. I often compose them as I’m walking, say, from the city centre, home. I type them up, make sure they’re less than 200 words, then post them on Facebook. I like the near-spontaneity of it—very different from how I normally work. It’s a little madness. I didn’t revise them, so reader comments, while nice, had no influence on them. I’d never be tempted to put work-in-progress up on Facebook. I don’t want to know what readers think until I know the work is finished. KM: What are you working on now? RD: I’ve just finished a novel, called The Guts. It’ll be out here and the UK in August, and the USA early in 2014. I’m writing a short story, about a man who’s injured when another man, in Lycra, cycles into him. I’m also working on a treatment for a possible TV series. ‘Possible’ is code for ‘It’ll never be made.’ I’m enjoying the job. Later this year, a musical based on my book, The Commitments, will go into rehearsal. I wrote the script, the ‘book’, so that will take up a lot of my time. I’m very excited about it. I’m tempted to say ‘I can’t wait’ but, actually, I can—just.  RODDY DOYLE'S LATEST BOOK Two Pints, published by Jonathan Cape, Vintage Publishing, 2012 Description from the publisher: Two men meet for a pint in a Dublin pub. They chew the fat, set the world to rights, take the piss… They talk about their wives, their kids, their kids’ pets, their football teams and--this being Ireland in 2011–12--about the euro, the crash, the presidential election, the Queen’s visit. But these men are not parochial or small-minded; one of them knows where to find the missing Colonel Gaddafi (he’s working as a cleaner at Dublin Airport); they worry about Greek debt, the IMF and the bondholders (whatever they might be); in their fashion, they mourn the deaths of Whitney Houston, Donna Summer, Davy Jones and Robin Gibb; and they ask each other the really important questions like ‘Would you ever let yourself be digitally enhanced?’ Inspired by a year’s worth of news, Two Pints distils the essence of Roddy Doyle’s comic genius. This book shares the concision of a collection of poems, and the timing of a virtuoso comedian.  Linda Svendsen Photo by Michael O'Shea Linda Svendsen's linked collection, Marine Life, was published in Canada, the United States and Germany and her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Saturday Night, O. Henry Prize Stories, Best Canadian Stories and The Norton Anthology of Short Fiction. Marine Life was nominated for the LA Times First Book Award and released as a feature film. Svendsen’s TV writing credits include adaptations of The Diviners, At the End of the Day: The Sue Rodriguez Story, and she co-produced and co-wrote the miniseries Human Cargo, which garnered seven Gemini Awards and a George Foster Peabody Award. She received the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006. Svendsen is a professor in the Creative Writing Program at the University of British Columbia. RUSTY TALK WITH LINDA SVENDSEN Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Linda Svendsen: In Grade 2, we were asked to write a rhyming poem and I had so much fun doing it that I went on for a dozen stanzas. Building on this major breakthrough, in Grade 3 I tried to write a sequel to Tom Sawyer in which Becky and Tom married (roughly 6 pages of careful heartfelt printing). KM: Why did you decide to become a writer? LS: I don't think I ever decided to become a writer; it's happened by default and I still wonder how it's all going to turn out. All I know is that I really enjoy writing fiction and for screen and that it allows me to pursue all the other activities I considered such as acting, directing, producing, social work, anthropology, history, etc. KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use? LS: Nancy Packer, fiction writer (and mother of New Yorker writer George Packer and novelist Ann Packer) told me to take my characters to the cliff. And push them over. KM: Your new novel, Sussex Drive, is a political satire offering readers a behind-the-scenes look at Canadian politics. Why did you decide to take on this subject matter? What do you hope readers take away from it? LS: Sussex Drive was inspired by Canada's federal prorogue-a-palooza in 2008 and 2009. It's about a Conservative Prime Minister's wife and a left-wing Governor General and what happens when they can no longer play "Follow the Leader." I was very intrigued by the Governor General's role and decision-making in December 2008—would she or wouldn't she allow the Harper government to fall and the coalition to take power? Also, as Canadians, we're immersed in the entertainment/propaganda of the U.S. and U.K. (and their political figures with The King's Speech, The Queen, Game Change) and our own turf seemed rich and virtually unexplored. And it's chick lit, too, for canuckleheads. KM: Sussex Drive reads like it’s written by a political insider. How did you approach the research for this project? Can you tell us about the process of writing this book? LS: Sussex started out as a short story after December 2008 and headed toward novella length. After the 2009 prorogation, it became a novel and I visited Ottawa—the Parliament Buildings, Rideau Hall, Gatineau Lake, Museum of Civilization, the War Museum, and Rockcliffe Park. I happened to be in London in April 2009 during the G-20 and found it fascinating that the Canadians seemed to be invisible to the British press. Random House Canada bought the novel in October 2011 when I had 140 pages written; I wrote from January to June 2012 (my editors were amazing!) and it was published last October. Tight deadline! KM: Many reviewers have commented on the sharp dialogue in Sussex Drive. In addition to writing fiction, you’re also an awarding-winning screenwriter. Do you plan on adapting Sussex Drive for film or television? If so, how do you plan on approaching the adaptation? LS: I'm trying to talk my husband into producing Sussex Drive, but he's busy with other projects right now. 6 x 1 hour or a TV movie...fingers crossed! KM: What are you working on now? LS: Right now I'm deciding what novel I'm writing next. Great space to be in.  LINDA SVENDSEN'S MOST RECENT NOVEL Sussex Drive, Random House Canada, 2012 DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER A startingly funny and deeply satisfying satirical novel that makes the Canadian political scene accessible from the female perspective, behind the scenes at the top of the hill. Torn from the headlines, Sussex Drive is a rollicking, cheeky, alternate history of big-ticket political items in Canada told from the perspectives of Becky Leggatt (the sublimely capable and manipulative wife of a hard-right Conservative prime minister) and just a wink away at Rideau Hall, Lise Lavoie (the wildly exotic and unlikely immigrant Governor General)—two wives and mothers living their private lives in public.Set in recent history, when the biggest House on their turf is shuttered not once, not twice, but three times, Becky and Lise engage in a fight to the death in a battle that involves Canada’s relationship to the United States, Afghanistan and Africa. The rest of the time, the women are driving their kids. From Linda Svendsen’s sharp and wicked imagination comes a distaff Ottawa like no other ever created by a Canadian writer, of women manoeuvring in a political world gone more than a little mad, hosting world leaders, dealing with the challenges of minority government, and worrying about teen pregnancies and their own marriages. As they juggle these competing interests, Becky and Lise are forced to question what they thought were their politics, and make difficult choices about their families and their futures—federal and otherwise. EXCERPT FROM SUSSEX DRIVE  Lisa Robertson For many years LISA ROBERTSON has worked across disciplines and often in collaboration. With the late Stacy Doris she was the Perfume Recordist, an ongoing sound performance and writing project with work in the new I'll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women. She worked as The Office for Soft Architecture, publishing reports, essays, walks and manifestoes as well as curating and cooking as OSA. Currently she is translating the French linguists Emile Benveniste and Henri Meschonnic with Avra Spector. Her most recent book of poetry is R's Boat, from University of California Press, and Bookthug published a new book of essays, Nilling, in spring 2012. She lives in rural France, and teaches at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. RUSTY TALK WITH LISA ROBERTSON Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative? Lisa Robertson: I think my earliest creative acts were acts of deception and truth bending—petty theft, rebuttal, cover-up. This led directly to writing. KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.) LR: Everyday I sit in an armchair and write in a notebook as I read. If somebody gives me resources I leave the armchair and travel to read in an exotic library. Writing on trains and airplanes on the way to and from these libraries is a special pleasure, because so much anticipation and repletion is involved. Talking to my friends usually shows me how to work with the material I have gathered. My dearest friends are the ones I simply obey. KM: How would you define experimental writing? LR: I wouldn't define experimental writing. It would cease to be experimental then. KM: What influences your work? LR: Unanswerable questions. Unanswerable to me that is. Right now I am trying to understand the movement a triangle sections, and I am trying to understand the humoural system of medicine. Put more simply, desire influences my work. KM: What have you read recently that excites you? LR: I just spent a month reading at the Warburg Institute in London, for 6-8 hours a day, six days a week. Everything excited me. I was reading about the relationships between geometry, astronomy, optics, and medicine in the ancient world, until the baroque era and Johannes Kepler's work on the elliptical orbits. I wanted to understand the dynamics of the ellipse, and I wanted to understand science as a relational query into the structure of the cosmos, rather than a recitation of the mechanics of cause and effect. Plato's Timeaus is hallucinogenic in that respect. So is Kepler's The Six-Sided Snowflake. So is medieval Arabic optics. These studies are enticing me to draw more, and that is a pleasure. In terms of recent poetry—Erin Moure's translations of Galician poet Chus Pato, Aisha Sasha John's new work, Angela Carr, the American poet Chris Nealon, and Francis Ponge. I read Ponge as a contemporary. KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you've heard or been given that you actually use? LR: Writing is the good use of boredom. I try to have a boring life. I don't socialize, and I eat nine servings of vegetables a day. KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one. LR: When Jam Ismael read at KSW in 2002 she sat a tape recorder on a windowsill and played a cassette recording of New Delhi crows. Vancouver crows came to the open window to listen and respond. Every emotion cracked open at once. KM: What are you working on now? LR: I am simply reading and learning, and making the occasional paragraph or drawing as record and exploration.  LISA ROBERTSON'S MOST RECENT BOOK Nilling, Bookthug, 2012 Description from the publisher: Nilling: Prose is a sequence of 6 loosely linked prose essays about noise, pornography, the codex, melancholy, Lucretius, folds, cities and related aporias: in short, these are essays on reading. Excerpts from Nilling: EXCERPT 1 I have tried to make a sketch or a model in several dimensions of the potency of Arendt's idea of invisibility, the necessary inconspicuousness of thinking and reading, and the ambivalently joyous and knotted agency to be found there. Just beneath the surface of the phonemes, a gendered name rhythmically explodes into a founding variousness. And then the strictures of the text assert again themselves. I want to claim for this inconspicuousness a transformational agency that runs counter to the teleology of readerly intention. Syllables might call to gods who do and don't exist. That is, they appear in the text's absences and densities as a motile graphic and phonemic force that abnegates its own necessity. Overwhelmingly in my submission to reading's supple snare, I feel love. EXCERPT 2 In the facsimile Oblongus Codex, at the bottom margin on the page containing lines 1140-1159 of the fourth book of De rerum natura, I saw what at first appeared to be the photographed image of a small oval hole about the size and shape of my thumbnail, tidily cut from the vellum of the original. Bordering this ellipse, I saw a faint drawing that added a labial ornamental border around the shape. It seemed that some sort of monkish pornographic doodle had been censored. At closer examination I realized that the elliptical absence had in fact not been cut from the page by some historical censor--it was rather a flaw inherent in the structure of the vellum; the trace of a wound perhaps. Several of these photographed images of material mise-en-abimes appeared as I leafed through the codex. In each case the page was cut from the larger skin so that the scar found its place in a margin, so as not to interfere with the scribe’s work. But here in book four, the scribe had decorated the flaw in the skin with this mildly and endearingly erotic doodle. The tiny absence was animated: a lacework. |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed