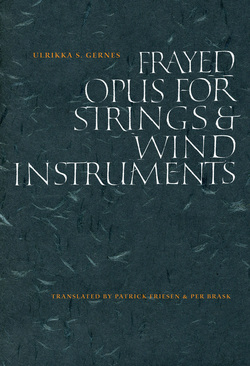

RUSTY TALK WITH ULRIKKA S. GERNES, PATRICK FRIESEN & PER BRASK Patrick Friesen is a poet, essayist, playwright and translator living in Victoria, B.C. His most recent publications are jumping in the asylum (2011), a dark boat (2012) and a short history of crazy bone (2015). He has co-translated five volumes of poetry with Per Brask.  Per Brask is a Professor in the Department of Theatre and Film at the University of Winnipeg where he has taught since 1982. He has published poetry, short stories, drama, translations, interviews and essays in a wide variety of journals and books. This is his fifth volume of poetry co-translated with Patrick Friesen. Danish poet Ulrikka S. Gernes collaborated with Canadian poets Patrick Friesen and Per Brask on their English translation of her Flosset opus for strygere & blæsere (Gyldendal, 2012), the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize-nominated Frayed Opus for Strings and Wind Instruments (Brick Books, 2015). It is the second book they have worked on together, having previously collaborated on A Sudden Sky (Brick Books, 2001). Gernes is an acclaimed poet in Denmark, where she also manages the estate and artistic legacy of her father, the Constructivist artist Poul Gernes. Friesen, from Steinbach, Manitoba, teaches at the University of Victoria and is also a playwright, as is Brask, who teaches at the University of Winnipeg and has worked extensively in theatre. Brask came to Canada after training as a dramaturg in Denmark. --Rebecca Rustin Rebecca Rustin: While Frayed Opus for Strings and Wind Instruments eschews direct religious references, Per, you made the remarkable decision to convert to Judaism (For love? I was born to the troubled tribe), and you, Patrick, deal head-on with religious themes in your play The Shunning (Scirocco Drama, 2010), about the Mennonite community you grew up in. Ulrikka's second book was Englekløer (Borgen, 1985), the title translated by Per and Patrick as Angel Claws. Per's work is concerned with, among other things, philosophy (Nietzsche, Badiou), Graeco-Roman classics, and mid-twentieth century European politics. It seems that Patrick and Ulrikka ultimately cleave to the pagan--land, sea, animals, the elements--in terms of anchoring the self to the broader world. How does the divine and/or the pagan (to use the term loosely; I might as well just say 'nature') figure into your thinking about the world, and inform your writing/translation practice? How do you use the subject's direct relationship with nature to find your own path through the dominant narratives of the communities you grew up in? Ulrikka S. Gernes: I am not an agnostic and I'm even anxious about using such a word, since I do have a firm belief that ”there's more between heaven and earth than flesh and blood” (line from a poem). As a poet I must never cast my eyes down. I am on the side of the human spirit, the human condition ... I must carry those few drops of water in the palm of my hand through the desert. I once summed it up like this: ”Poetry, in any language, is a language of resistance, resilience, resonance, that speaks from the core and from the rim, from inner and from outer space within the experience of human existence.” One could ask where that thinking comes from? Of course it has to do with the ethics that are fundamental in most world religions and hence are part of our social and cultural ”foundation”, but as Patrick pinpoints it: ”One is a physical and spiritual animal.” I guess that is the point of departure for my work as a poet. Per Bask: When my wife, Carol Matas, and I got together some forty years ago we quickly became aware that we wanted to make a go of it and that our life together would include children. We decided early on that those children would be raised as Jews—and they have been. That meant that I had a lot of catching up to do and I began to study Judaism. The more I got into it the more fascinated I became and eventually I fell in love with the conversation Jews had had down through the ages about life and God and what we humans owe to each other and to God. I wanted to join that conversation as a member. We are not a religiously observant family, but we celebrate Shabbat and we are committed to a spiritual Judaism that is eclectically informed by different denominations. My recent poetry comes from this outlook, this engagement with life. It has also led me to translate the Danish Jewish thinker Andreas Simonsen. Patrick Friesen: A community is many things. Some communities have a basic religious approach to life, though every community has its dissenters, or outliers. I found myself resisting the fundamentalist Christian approach prevalent in my community, and central in my family. While the theological aspect was important, the intrusiveness of those who thought they had a right to probe the state of my soul and to judge it was perhaps the most important part of my resistance. I am interested in both the state of my own spiritual existence and in the social and political aspects of world religions. One is a physical and spiritual animal. I doubt I’m a pagan, though that would be a lovely label to carry. I don’t know if there’s one single word that indicates what I am. Some days I feel I’m an atheist, other days an agnostic, and there are even days where I might come close to some kind of Christian mysticism. But I don’t really know. I do feel that essentially I’m a material being with a spirit, and I have a good sense of what happens to matter after death. What I don’t have a firm grip on is what happens with spirit. RR:I know I said I'd stay away from boring process-y questions, but Patrick, in the interview you recently gave Vancouver's Roundhouse Radio you said something that sounded kind of fun, about the early days of you and Per's collaboration in translating Danish poetry, when he would come sit on your couch and you guys would hammer things out. How does it look when the three of you get together? USG: Our collaboration has unfortunately mostly taken place in cyber space (not many drinks involved) in a rainbow of emails exchanging suggestions, corrections, comments back and forth, and for me it felt like a complete luxury that two wonderful people on the other side of the world would take such care, use their linguistic strength, intelligence and sensitivity—as well as their precious time—to choose and shift around words in poems and stick by them until they fitted hand in glove into the poem. PB: Email with the addition of the telephone has made our work possible since Patrick moved to BC. PF: The three of us never get together physically in order to discuss the translation we’re involved in. Email and telephone is how we communicate. With Per and myself the occasional phone call is essential so that we can hear what we’re doing. RR: When John Weiners, at the time a prodigious drinker of Carling Black Label beer, won a NEA grant, he simply switched to champagne. What's the silliest thing you've ever done with an unexpected windfall? Would you do something silly with the prize if you won? Why is money such a vexed question with regard to the arts? Is money evil? USG: Money? Well, rent has to be paid. Honour doesn't buy breakfast. Money; it's tough when you don't have it. I guess the point is to have enough. Money can do great things and change lives, but money itself doesn't interest me. I know that that sounds arrogant and is a sure sign I'm spoilt silly with the privileges of having been born in a wealthy part of the world, but one must remember: life itself is not long! I am sensible with money (grew up in an artist family with no money) knowing that money—or perhaps a windfall?—can buy freedom to do other things such as writing poetry. There's hardly ever money involved in poetry. Up to now Per and Patrick have basically worked for free. Actually the fee paid for reading at the Griffin is the first real money they get for this book because it is shared between us and that makes me happy (and if we hit the jackpot, naturally that is shared too!). PB: I’ve never had a windfall. Should one happen I can only say: 7 grandchildren PF: People of Mennonite background don’t do silly things, surely everyone knows that. But I think investing a windfall would be quite silly. It’s not something I have to worry about. RR: Patrick's first language was, I think, Low German, Per's was Danish, and Ulrikka, growing up Danish in Sweden, perhaps you learned Swedish, Danish, and English at the same time? How do you all feel about the relationship between English and your mother tongues? Do you wish it were easier to make delicious compound words in English, as you can do in German and Danish? Are there things English can do that Danish can't? USG: Different languages have different advantages and disadvantages. Certain things are more easily, precisely or poetically expressed in Danish than in English and vice versa. There are words ”lacking” in both languages. One language will have an abundance of synonyms while the other has an empty gap in a particular field. For instance the Danish word døgn, which is a word for day and night together, for the full 24 hours, English, curiously, doesn't have a word for that. Translating døgn you have to either choose day or night or say 24 hours and that can completely shift the meaning and feeling in a poem. Danish is my mother tongue, the language I feel the most intimately connected to (spiritually and physically) despite the fact that I am born and grew up in Sweden and speak fluent Swedish. It is interesting that somehow mother tongue and mother's milk are almost synonymous—language is part of the nourishment. However, English was a ticket to the whole world in a sense, allowing me to travel and live in other parts of the world. I have a fairly good command of English, but when it comes to the subtle details, the shades and nuances, the flavors, I depend on Patrick and Per. PB: Those compound words in Danish and in German are usually pretty awful, in my view. English has a much larger vocabulary and I find that endlessly engaging. PF: Compound words are mostly very useful, but in translating you often have to split compound words in half, or possibly in threes, and then you have lost a lot. Perhaps if you’re lucky you’ll find a compound word in English that approximates the Danish compound word, but it’s doubtful. But you might find a word that catches part of the compound word and adds something new to the poem. Suddenly, the poem changes a little bit, and it’s up to the translator to decide if this change in fact helps the poem in its new language without straying too far from the original. RR: What kind of music do you like right now? Anybody ever play an instrument? Smash a guitar onstage? Per, you're a librettist. What a beautiful word. Do you sing? USG: I wish I could sing, or play an instrument! I wish I could express myself without leaving behind a monument to failure ... Music has this ability to push through barriers in the brain and touch us in a direct and immediate way and hence influence emotions, atmosphere, sentiment, we have little defense toward music, and it is also curious how lines from songs or snippets of tunes and melodies can pop up in your heads triggered by an emotion, or a chemical shift in the body. The same way music can put you in different moods. I used to listen to a lot of music, and I still do, and many different types of music, but find that I ”use” music, sometimes as tools to access certain ”moods”, or to get energy, or to get myself out of a certain mood. Music can pour from an open window and completely blow you away ... PB: The Rolling Stones never get old for me. I’ve written two pieces for the composer Michael Matthews, one a piece for actor and cello and the libretto for Matthews’s opera Prince Kaspar. I do not sing. Way back in the mid to late 1960s I played bass guitar in rock and roll bands, eventually dropping the bass and becoming a lead singer (read: screamer). I was never good at either but I love good bass riffs and in my writing and translation it is a bass line that plays in the back of my mind. PF: I like a lot of different kinds of music. I loved the rock ‘n’ roll of the 60s, especially what was coming out of England in the middle of that decade. I particularly love garage-band records, like Shakin’ All Over by Chad Allen & the Expressions, and what used to be called novelty records, like Surfin’ Bird by the Trashmen or Muleskinner Blues by the Fendermen. I loved the wildness in rock, the letting go, the sheer exhilaration and mad laughter. I love all kinds of jazz, people like Bill Evans, and classical music, from Mozart to Arvo Part. I love fado and cante jondo. The list goes on. I can read music and took piano lessons, but I ain’t no player, and I’m no singer either, but music plays a central part in all my work. RR: How do the dramatic scenes encapsulated in each of Ulrikka's poems speak to your, Patrick and Per's, experience in theatre? Have you, Ulrikka, ever been involved in theatre in any way? USG: I've never tried my hands at writing for the theatre, but when writing poetry I often have this ”stage” in mind where something happens, where people interact, or nothing happens and you wonder why. As a child I loved radio plays. Maybe because we didn't have a TV. I think the attraction was that images developed in my head, I was actively involved and that was very engaging. I still love to listen to radio drama when I'm moving around Copenhagen on my bicycle. A Danish actress once told me about an exercise her acting group had done where each actor and actress had picked a book randomly. The task was to act improvisations from the texts they randomly chose. Chance had it that she had picked one of my poetry collections and the whole group was surprised how well my poems had worked ”dramatically”. I wish I had been a fly on the wall there. PB: In addition to that bass line, I need to sense the gesture of a piece before writing or translating. I believe that comes from my theatre training. PF: In addition to the actual theatrical writing I’ve done, I think there’s an element of theatre in some of my poetry; that is, I often have voices in my poems, implied or actual. There’s a lot of conversation in my work, often internal. I think I always look for that conversational motion in other people’s work. RR: Ulrikka and Patrick, you've drawn a distinction, in the Afterword to Frayed Opus and in the Roundhouse interview, respectively, between melancholia (Ulrikka) or the doldrums (Patrick), and depression. It seems as though North American culture overclinicizes things sometimes. Or demands that everyone 'think positive.' Would you expand a bit on the subtleties of negative emotion--the kind that calls for medication versus the kind everyone lives with? Anyone: European versus North American approaches? Is there an equal balance of joy and misery in the world? USG: Patrick suggests reading Lorca and Per points out the importance of visits to the darkness. I absolutely agree! Now, I will be a little bit cheeky and answer your question by guiding your attention to a fantastic painting by Lucas Cranach The Elder because that painting for me sums up melancholia in a beautiful, philosophical and intelligent way. I would prescribe meditating on that painting before taking any medication! We are fortunate to have that painting in the collection of the National Gallery in Denmark so I have seen the original many times and I still go to see it every now and then—when I need a bit of that medicine! PB: That’s Jacob’s struggle, the struggle we all have with life and the divine—whatever we chose to call that. But depression is real, horrible and not recommended. Melancholy thoughts, visits to the darkness, on the other hand are necessary for reevaluation and getting better at life—I think. PF: Ah, yes, much has been medicalized which shouldn’t be. I recently heard that grief is now considered a “disease”. We medicalize, and we categorize, to the point of absurdity. Melancholy is essential I think. As are grief and sorrow and even moments of despair. Experiencing darkness is important simply for living our lives, but it certainly plays a part in the creation of art. A lot of the best work is done in “altered states”. But, of course, it’s always a balancing act, a risky business. One can get lost in darkness, or in an altered state. Venturing there requires a certain amount of courage and the strength and pragmatism to get out. Read Lorca on this subject; his poems but also his essays. His concept of duende is central to his literary output. Frayed Opus for Strings and Wind Instruments |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed