RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL LONGLEY Michael Longley Michael LongleyPhoto credit: Kelvin Boyes Michael Longley was born in Belfast in 1939. He has published nine collections of poetry including Gorse Fires (1991) which won the Whitbread Poetry Award, and The Weather in Japan (2000) which won the Hawthornden Prize, the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Irish Times Poetry Prize. In 2001 he received the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry and in 2003 the Wilfred Owen Award. He was awarded a CBE in 2010 and was Ireland Professor of Poetry, 2007-2010. Catherine Graham: Congratulations on winning the Griffin International Poetry Prize for your tenth collection, The Stairwell (Cape Poetry). Like a stairwell, this book contains poems of passages—birth and death, childhood and old age, conflict and peace. During your acceptance speech you mentioned that you’ve been writing since you were 15. Was there a moment when you realized you were a poet or was it something that just built up over time? Michael Longley: It built up over time. I feel very superstitious about calling myself a poet. It’s what I most want to be. CG: The Stairwell consists of twenty-three elegies for your twin brother, Peter. Homer’s Iliad also permeates the collection. I wondered if you could talk more about how this book came into being. ML: I was with Peter when he died. At the time I wondered if I would ever be able to write an elegy for him. I ended up writing twenty-three. I gathered them into the second half of the book as a sustained lamentation. As so often in the past Homer came to my rescue and helped me to find the words. In some of the poems in the first section I celebrate grandchildren, and that lightens the elegiac tone a bit. Arrivals and departures. CG: When you were a student at Trinity your first poem “Marsh Marigolds” was published in a literary magazine called Icarus: She gave him marigolds The first three lines are weaved into “Marigolds, 1960” uniting the young poet you were with the experienced poet you became. It’s one of my favourites in The Stairwell. Can you tell us more about this poem and/or the process behind it? ML: The poem was published in the Trinity College literary magazine Icarus at Easter 1960. Although I didn’t realise it at the time, my father was dying. He discovered the poem and told me it wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. He was right of course, but he shouldn’t have said that. In ‘Marigolds 1960’ I forgive him his frankness, but much more importantly I grieve for him and suggest that at the end we were drawing closer together. It pleases me that my juvenile verse helped me in my seventies to frame an elegy for my father. CG: You have said at this point in your writing life you have “all the tools for producing forgery and it’s important not to.” What constitutes forgery for you? ML: Faking emotions. Imitating yourself. Pretending you have something to say when you haven’t. Passing off five-finger exercises as true art. Silence is infinitely preferable to such shams. Indeed, silence is part of the enterprise. CG: Who were some of your early influences? ML: Walter de la Mare, Keats, e.e. cummings, Louis MacNeice, Auden, Yeats, Wilfred Owen, Edward Thomas, Hart Crane, Dylan Thomas, Richard Wilbur, D.H. Lawrence, Theodore Roethke. I was quite promiscuous. CG: What are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen in the world of poetry since you started? ML: The word processor and the way it encourages you to mistake garbage for the real thing. The Creative Writing industry and the retreat of poetry into academe. A good poem is just as rare an event as it always has been. CG: Can you share some of the highlights of your Griffin experience? ML: Meeting my fellow poets and sharing with them the nervy excitement of it all. Being charmed and impressed by Scott Griffin and reassured by his marvellous staff. Not expecting to win and then winning. Phoning my wife in Belfast to give her the good news. The bigheartedness of the whole enterprise. The vision and the details. CG: What’s next for Michael Longley? ML: I have written about half a new collection of poems. I am also putting together a selection of my prose – essays, lectures, introductions, articles, reviews. And I am working on a memoir – before I forget everything . . . MICHAEL LONGLEY'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

"Dementia became a metaphor; I began to see the time we’re living in through a lens of dementia." |

Jane Munro: That’s a good question. I remember feeling it was hard to justify spending time on poetry—instead of doing something obviously useful—when there was no external evidence that I was a poet.

As a young mother with three children, I'd go so far as to ask myself, if I weren't me but a young male poet deciding whether to hire a babysitter so he could work on poetry or save his money and spend time with his kids, or some other such choice I found difficult, would I know what to do?

I’d know. It wasn’t always the same answer, but when I called myself a poet and took being a woman out of the equation, I’d know what it was best to do.

Even after I’d published books, being a poet felt different from being someone who composed poetry. I juggled writing time with time for family, earning a living, studying. Did real poets live the kind of life I was living?

At some point, I stopped worrying about whether or not I was a poet.

Perhaps the turning point came when I figured out that my best contribution to the welfare of the whole was to be myself – liver cells didn’t help the body by trying to be bone cells (not that they had such a choice) – and that being oneself wasn’t “selfish” (my mother’s accusation about artists). It also helped to grasp that even DNA is flaky: mathematicians could devise a stronger code.

CG: The first of four sections, “Darkling,” is a sequence of poems numbered one to twelve that seems to counteract a husband’s descent into Alzheimer’s by celebrating the physicality of life with its vivid, precise and sensual imagery: “the glans of a penis, smooth as an acorn,” “The stone that made me think of a full soul / smooth and heavy in my hand,” “A candle guttering.” In the second Darkling, the defiant line “Peeling the grape of death” appears. Your poems are like peeled grapes, more flesh is revealed as one reads them through. Can you tell us about the origin and development of this book?

JM: In a crisis, sealing off vulnerable parts may allow you to do what’s essential. But when it’s not exactly a crisis, even though your reality is a slowly aggregating disaster (such as dementia or what’s happening with climate change), locking yourself into coping mode (being hide-bound) isn’t synonymous with self-protection. But it’s easy to get trapped in the pain of grief.

When I started writing the poems in Blue Sonoma, I had classic responses to pain: anger, self-pity, helplessness, hopelessness. I was even afraid my own life was over.

Making art took heart, mind, body and spirit. Working on the poems made me feel whole. There wasn’t any choice about vulnerability. Peeling the grape of death meant more flesh was revealed.

Dementia became a metaphor; I began to see the time we’re living in through a lens of dementia. If the poems were to provide architecture for the imagination of others, they had to be inhabitable. I didn’t think of them as mine though they came through me and drew on my resources. That’s why I like doing readings: it’s my chance to sense the poem complete its transitive arc; feel others move into it, furnish it with personal stuff.

I don’t know if this answers your question. I wasn’t in any rush to finish the book.

CG: It does answer my question, thanks. In the section “Dream Poems,” dream-reality is reproduced through stark and stirring imagery. These poems are often laced with a post-dream realization such as the last line from “The net of heaven is cast wide”: “He is not a person I knew in life.” Could you tell us more about your relationship with poetry and dreams?

JM: In the iceberg of consciousness, the vaster realm floats beneath the surface of day-to-day thought. Sometimes, I feel that we all share an unconscious reservoir of imagery and story.

While I was writing Blue Sonoma, I was recording dreams. This kept me in a conversation with images from the less-conscious parts of my mind. If I’m right that we share some of this material, then dream imagery might also connect with deeper layers of the reader’s consciousness.

Not every dream comes from that level; some appear to simply recycle a day’s debris. The poems in the second section of the book are records—translations—of specific dreams. Many of the other poems in Blue Sonoma draw on dream imagery, or move as dreams move. Each of them was a mystery. During its gestation, I’d be curious to meet it. For some, that took a long time.

CG: The spare and moving 11-part sequence “Old Man Vacanas” is cutting in its frankness and dark with black humour. The consistency of the voice addressing or observing “the old man’s” struggle with dementia links the poems into a cohesive monologue. How did this section come together for you?

JM: The “Old Man Vacanas” are contemporary approximations of an ancient poetic tradition. In Kannada, a South Indian language, vacana means “saying; thing said.” Vacanas are colloquial prayer poems using natural and domestic imagery to voice—often, complain about—family, village, spiritual, and philosophical issues. Unlike poetry in Sanskrit, they aren’t aureate.

The 12th Century vacanas were prayers addressed to Shiva—or, more precisely, to the poet’s personal deity (Mahadeviyakka calls on “my lord white as jasmine”). In “Old Man Vacanas” the “you” is not identified. I thought of the “you” as the listener.

The poems in this sequence started coming during a snowstorm when we were cut off—the roads impassable. I wrote one after another. This doesn’t happen for me very often, not with that intensity: every time I sat down, another came. I liked them and kept them. Later, others came. I couldn’t tell how long the run would be so played around with it over the next five or six years. Eventually, “Old Man Vacanas” came down to the set of eleven in Blue Sonoma. It was an odd number.

CG: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use?

JM: Write as if you’re already dead. This advice is attributed to Nadine Gordimer, but it reminds me of Krishna’s injunction to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita: surrender the fruits of your actions.

Yogis say we have the pleasure of doing our work but no control over its outcomes. That’s the thinking behind Karma Yoga (karma means action).

Yoga practices end with Savasana—corpse pose—during which you let go everywhere, release what you did or didn’t do, drop body and mind into stillness and silence. It’s refreshing and energizing.

CG: What were some of the highlights from your Griffin experience?

JM: Oh, my! It was all extraordinary: reading to over 1000 people—Koerner Hall filled with poetry and their attention; meeting and listening to the other shortlisted poets; the generosity and sincerity of the Griffins: their love for poetry, their vision, their attention to every detail; meeting the illustrious Griffin Trustees and jurors, many of whom I hadn't met before; the recitation by Ayo Akinfenwa (finalist in Poetry in Voice) at the gala; the way everything left me feeling hope for poetry. And, of course, winning: my daughters and friends with me—even distant friends and family watching. A Griffin has wings. I was transported.

CG: What advice would you give to an aspiring poet?

JM: Read and write, read and write, then read some more. Relax; be present; be curious; pay close attention; be patient.

CG: What’s next for Jane Munro?

JM: Writing: settling into my own rhythms and practices and work. That’s the main thing. This fall, thanks to an apartment exchange, I’ll spend a month in Germany. I was in India for two months last fall studying yoga. It’s ages since I had much time in Europe.

=

= Jane Munro

Brick Books, 2014

Winner of the 2015 Griffin Poetry Prize

A wise and embodied collection of dreamscapes,

sutras and prayer poems from a writer at her peak

In Blue Sonoma, award-winning poet Jane Munro draws on her well-honed talents to address what Eliot called “the gifts reserved for age.” A beloved partner’s crossing into Alzheimer’s is at the heart of this book, and his “battered blue Sonoma” is an evocation of numerous other crossings: between empirical reportage and meditative apprehension, dreaming and wakefulness, Eastern and Western poetic traditions. Rich in both pathos and sharp shards of insight, Munro’s wisdom here is deeply embedded, shot through with moments of wit and candour. In the tradition of Taoist poets like Wang Wei and Po-Chu-i, her sixth and best book opens a wide poetic space, and renders difficult conditions with the lightest of touches.

Grey wood twisted tight

within the framework of the tree –

impossible to snap off,

forged as it dries.

And in me, parts I can’t imagine

myself without – silvering.

~from “The live arbutus carries dead branches…”

Praise for Jane Munro:

“spellbinding … haunting … thoughtful, evocative … arresting images … Zen-like spirituality… ” ~The Toronto Star

Excerpt from Blue Sonoma, Brick Books 2014

In a small boat off Port Renfrew

caught the moon.

It was pale and pocked.

It lengthened from disc to oval to flat fish

as she lifted it. The rod bowed.

When the rod’s tip touched the water’s surface

the moon sprang from the wavesstreaming foam, and soared overhead.

The woman fell on her back –

winded, wordless – rocking as the boat rocked.

The moon hung above her

huge and closer than a star.

It had grown on a tongue of silt

at the river’s mouth, dark-side-down

resting on its mind-reading side,

then slid to deep waters.

Staring up at it, the woman knew it knew.

RUSTY TALK WITH GARY BARWIN

Other recent books include Franzlations (with Hugh Thomas; New Star), The Obvious Flap (with Gregory Betts; BookThug) and The Porcupinity of the Stars (Coach House.) He was Young Voices eWriter-in-Residence at the Toronto Public Library in Fall of 2013 and he is Writer-in-Residence at Western University in 2014-2015. Barwin received a PhD (music composition) from SUNY at Buffalo.

Barwin is winner of the 2013 City of Hamilton Arts Award (Writing), the Hamilton Poetry Book of the Year 2011, and co-winner of 2011 Harbourfront Poetry NOW competition, the 2010 bpNichol chapbook award, the KM Hunter Artist Award, and the President’s Prize for Poetry (York University). His young adult fiction has been shortlisted for both the Canadian Library Association YA Book of the Year and the Arthur Ellis Award. He has received major grants from the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council for his work. Recordings of his work can be found at PennSound.org and on his YouTube channel. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario and at garybarwin.com.

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Gary Barwin: I was a single cell. There was a flurry of macromolecules—DNA, RNA, a wad of proteins—and then I wrote another cell into being and I became two cells. I kept writing until I was millions. This was my mother tongue before I had a tongue. There was no editing, until my father cut my nails.

Unless, my first creative writing memory was when I was 6 and writing on little cue cards, making up a writing system that seemed to hold the largeness, the numinosity of what could be said. I wrote a bunch of strange little sentences that were spells or poems in this made-up script that didn’t “mean” anything. And I do remember writing “Cosmic Herbert and the Pencil Forest” a short story in Grade 5 and publishing it to sell at the school “White Elephant” sale. My first publication.

KM: You are probably one of the most diverse writers in this country. You are a poet, a fiction writer, a children’s author, a performer, an artist, and a musician—is there an art form that you have not tried but want or plan to? And how do you decide what genre or form a project will take?

GB: There are so many things I’d like to try. I can’t help wanting to try my hand at a variety of things. I feel that there are so many exciting and inspiring ways to imagine writing, how could I just settle on one?

I see a continuum of approaches to creative work. On one extreme, there are writers like Samuel Beckett who worked his entire long career on narrowing the focus of his writing until he arrived at the laser-like minimalism of his later work. And then there are the writers who explore many different modes of creation, all part of one big messy creative ecosystem. bpNichol was one of these. The composer/writer/visual artist/performer John Cage was another.

As for me, I am currently working on a multimedia piece that will involve sound poetry, spoken text, computer processing, live music, recorded music, video, visual poetry and dancing giraffes. Ok, I’m lying about the giraffes. They won’t be dancing. Unless, of course, they want to.

The whole shebang is inspired by the work of iconic Canadian writer of “borderblur,” bpNichol and uses archival recordings of his performances. So I guess the answer is, I’d like to explore ways to further combine my various interests. I’m also also really interested in exploring film. I’ve made a few short videos by myself and in collaboration and I’ve found it very inspiring. And I’d like to work with various kinds of computer processing of text—I mean beyond spell check. There are so many fascinating things that can be done with even simple programming tools to create interesting texts or interactive text-experiences. I’ve done a few, but I’d like to explore this more. I find these kinds of projects really amazing and attractive.

I’m also planning an art exhibition of my visual poetry work, which is something I’ve wanted to do since crayons.

In terms of how I decide what genre or form a project takes, it is like cell division. I start with one tiny bit of something and then try to follow what it wants to develop into, trying to be open to what it might be. Or sometimes, I consider a form or a genre and think, “Hmm. I wonder what I could do with that? What possibilities does it offer? How would it make me create something that would surprise me or take me away from myself and my usual way of doing things?”

KM: You’ve been very involved in the small press and chapbook scene as a writer and publisher. Can you tell us a little bit about how you got involved and how that community impacted your writing and publishing life?

GB: It’s probably terribly gauche to do this, but I’m going to shamelessly plagiarize an answer to this question that I gave in an interview with the writer/scholar Alex Porco a few years ago in OpenBookToronto.com. I could, like a student once told me he did with stolen essays, run it through Google translator, first changing into Chinese, then Urdu, then back to English so that it becomes an “entirely new essay,”—actually I do do that with some poems to see what interesting changes occur—but here’s my original answer in the original language, rejigged just a little bit:

I’ve been involved in the small press since 1985. In a creative writing class at York University, our professor, the brilliantly laconic and insightful Frank Davey [who then went on to teach at Western], told us about this event downtown called "Meet the Presses", a gathering of small presses devised by Stuart Ross and Nicholas Power. He encouraged us to create books and get a table. I did, and ended up attending both Meet the Presses and independent book fairs for the next thirty years publishing a series of broadsheets, chapbooks, and various ephemera for each event. Stuart, Nick, plus some others of us, re-formed Meet the Presses several years ago in order to create the Indie Literary Market. These kind of community-based writer/publisher events, along with readings and the online world have been a constant and important part of my writing and cultural life. They’ve really contributed significantly to my development as a writer and have been responsible for introducing me to many writers, publishers, friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and readers, and much writing which has been important to me. All of which made my last thirty years of engagement in the literary scene inspiring, collegial, pleasant, welcoming, intellectually engaging, and fun.

I see small press publishing and related events like the [Toronto] Meet the Presses Indie Literary Market as responding to, and facilitating community around literature and publishing. The technology of the book is not one merely of information technology, but interactive technology. Readers, writers, and publishers come together to share their joie de livre in a context that is outside the strictures of predominantly market-driven publishing. In the small press, we can turn on a dime because we don’t need thousands of dollars to continue. Our share-holders are people who share in our work by holding our publications in their hands, and share our mutual appreciation of independent literature and publishing.

Publishing is not a neutral act. It is implicitly political and aesthetic. The publishing is part of the aesthetic of the work, in terms of its look, its distribution, and how the audience interacts with the work, both in terms of reading it, engaging with its writers and publishers, and in how it finds its audience. In the small press, there is a reason, a conscious decision, to publish the works in the way that they do. The presses choose to publish in this form not because they have to, but because they want to. In this kind of publishing, success is defined as an authentic interaction between engaged writing, publishers, and readers. It’s good to be reminded that we can choose to shape how our writing is and not only be driven by market-, media-, or other social forces. And we don’t have to wait for these outside forces in order to begin to publish and create audience and to make the writing and the community that we wish to see.

KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve been given that you use?

GB: bpNichol (who I’ve now mentioned several times) told us in writing class, “to keep writing.” I think that’s wise. Implicit in this, though, is to keep being curious and exploratory in one’s writing. Not to keep writing the same thing or the same way, but to keep trying to get better, to keep actively considering what makes writing exciting and interesting, what works and what is possible. And one can’t write without being an active and engaged reader, and, for most of us, unless we’re Emily Dickinson, an active participant in a literary community. I also remember asking Lillian Necakov, the first one of my friends to have a book published, how she did it. She said, “You write one page and then you write another until you have a hundred pages. Then you have a book.” Also good advice!

KM: Collaboration seems to be a big part of your writing and creative life. You’ve collaborated with Craig Conley, Hugh Thomas, Gregory Betts, Derek Beaulieu, Stuart Ross and others. What draws you to collaborative writing? I’m sure it depends on the project, but how do you approach it?

GB: I first make it clear that I’m the better, more experienced part of the collaboration and that everyone should take their cues from me. And bring me coffee. Also, I’ve got this itch just an inch below my right shoulder blade and …

But, really, the excitement and fun of collaboration is being open to doing something different, to this strange hybrid, hydra-headed process that is collaboration. It is both and neither of the participants’ work. It is very freeing. It is my work, but it isn’t, so I feel even more empowered to try things, to go with the process, to go outside my own sense of self, or my sense of my identity as a writer or even, my sense of what works as a writer. I try to trust the process that happens between me and my collaborators. And the great secret of writing is that you can always change things—tweak, modify, revise.

Sometimes collaborations involve some planning ahead by discussing what the project will be; sometimes, it involves just jumping in and seeing what results. Sometimes, it is like playing tennis. One person serves up something that the other has to return. This can be a line, a paragraph or something else. Then the other person answers it. The answer may involve reframing the entire question, surprising, challenging, or confounding the collaborator. Sometimes we proceed line by line, stanza by stanza, or paragraph by paragraph. Sometimes each of us goes back and changes what has been written before. One thing I love about collaboration is that the act of collaboration (the ‘rules of engagement’) are created collaboratively and can change at any time.

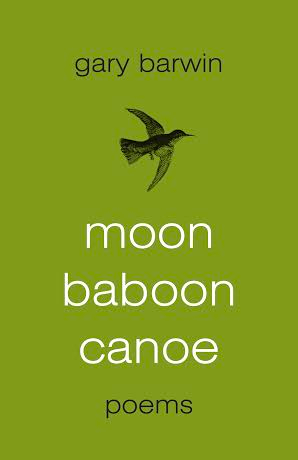

KM: In addition to being one of the most diverse writers in Canada, you are also one of the most prolific. In 2014 you published the poetry collection moon baboon canoe with Mansfield Press, you have collection of short fiction, I, Dr. Greenblatt, Orthodontist, 251-1447 coming out in 2015 with Anvil Press, and you have a novel Yiddish for Pirates forthcoming in 2016 with Random House. How are you able to write so much? Can you give us a sense of your process and how you move between so many different projects?

GB: I was going to write a self-help book “Making Procrastination Work for You!” wherein I describe how one can harness the power of avoiding working on one project by working on another, but I didn’t get around to writing it ...

I do find that I get energy from jumping from one kind of writing to another. Prose reminds me what poetry can do and vice versa. Sometimes, though, I do need to burrow deeply into something to give it time to develop—this was certainly was the case with the novel—but then after a long writing session, or sometimes intermittently in the middle of one, I’d write something else as a palate cleanser, on a lark as a diversion, or as a kind of footnote to the main project.

I think I write a lot because writing serves many purposes for me. It is a way of figuring things out, a way of working through things, a way of knowing, of experiencing things, of exploring. It is an entertainment, an obsession, a mode of social engagement, of doodling, of spiritual practice, of trying to become a “better” (more thoughtful? more compassionate? more observant?) person, a way of creating, experiencing, and responding the energy and possibility around me and in language.

In terms of process, I don’t know that I have a single mode of creation. Often it is the slow accumulation of work, chipping away at ideas or larger forms. I don’t know where I’m going. I have a place where I start writing, but I always consider that the writing knows more than me so I trust the process of writing itself and where it is taking me rather than my ideas for the project. I try to listen to where it is going. I means lots of revision and recalculating.

For example, I had some ideas about the novel and where it might go. I even had charts! But they were flexible. I’d head to where seemed the most promising direction. Then when I got there, I looked around to see where next: which was the most interesting direction from this new perspective. And so I kept moving forward. You know that nursery rhyme, “The Bear Went Over the Mountain to See What He Could See?” That’s how I imagined it. I’d walk to the mountain to see what I could see. And then when I got there, I’d look to see if I could see the next mountain from where I’d be able to see what I could see. Until 115,000 words later, I felt I was done.

KM: For readers who are first introducing themselves to your work, moon baboon canoe might be a good place to start because it’s a great example of the scope of your writing. The poems in this collection are humorous, nonsensical, profound, personal, absurd, political, and experimental. It’s a goodie bag of poems where each one offers a new surprise. How did this collection come together? Was it written over a long or short time span?

GB: Thanks for your kind words. Though I do like books organized around a central idea or theme, I also like books that are, as the pirates say, a salmagundi, a mish-mash. In moon baboon canoe, I hope that the various kinds of poems offer an energetic and/or supportive contrast.

I had lots of different kinds of poems kicking around, but Stuart Ross, the editor, and I discussed what kind of a book this might be and so I gathered the appropriate poems together. I shaped the book into sections so that it wasn’t just a big blob of stuff, but rather several smaller more shapely blobs. (That’s like choosing what clothes to wear…) It is a bit like creating set-lists for a band. You shape each set so that it has variety, coherence, and a certain shape or direction. And then you smash all the instruments and jump into the audience. And destroy your hotel room. Oh sorry. That was only when I was in that string quartet.

Most of the poems in moon baboon canoe were written in the few years preceding the book and then intensely revised, both before I submitted the book and after consulting with Stuart. Knowing that it would be Stuart who would be looking at the book gave me ideas about revision. I could internalize some of what I thought he might say which enabled me to see the poems with fresh eyes. And then, of course, when he did actually did see it, he did have some comments and suggestions that I hadn’t thought of. I actually love the process of working with a good editor. It is a productive dialogue and a chance to not only fix problems, but to learn of opportunities to make the writing do more. I didn’t always take Stuart’s exact suggestions, but I did listened carefully when he pointed out weaknesses or flabby bits which I could rework, revise, and generally improve.

As I said, most of the poems were written in the last few years, however, there are a couple that come from a long time before that. One of them I wrote as an 18-year-old undergrad. I was quite chuffed at the retroactive validation, that, at least, as far as that poem went, I wasn’t as entirely clueless as I thought I was back then.

KM: One of the things I enjoy most about your poetry is your sense of humour. In the poem “inside” which starts with the lines “inside Stephen Harper / there’s a little dog” you marry humour and politics into a thematically satisfying and entertaining poem. Poetry often has a reputation as a serious art form. When I talk to writers and readers new to poetry, they are surprised when poetry is funny. Can you discuss your thoughts on humour and poetry? Who are some of your influences?

GB: I don’t know why poetry and humour should be thought of as antithetical. Or why humour and “profundity” or depth should be thought of like oil and waiter, Angelina Jolie and Don Cherry, or iPhones and the duodenum. I think of humour as one of the great resources of communication. To surprise, confound, reconfigure, challenge assumptions, to enable lateral thinking, and more complex perspectives. Many traditions recognize this. For example, the spiritual masters who wrote Zen koans, Sufi parables, or Three Stooges shtick. And English: what a delightful narrative of confounding syntactic jokes, slippery orthographic pratfalls, and historic and lexical legerdemain.

two roads diverged in a yellow wood

I took one

it doesn't matter which

I'm not giving it back

Thinking specifically about humour in poetry, my influences from contemporary poetry include David W. McFadden, James Tate, Stuart Ross, Ron Padgett, Lisa Jarnot, Mark Strand, Steve McCaffery, and I’m going to have to mention bpNichol again (and here, I’m thinking of his sly visual work.) I think I’d also have to include John Cage and Wallace Stevens, More recent influences would include Anne Carson, Gabriel Gudding, Mary Ruefle (do you know her amazing lectures, Madness, Rack, and Honey?) Heather Christle, and Dorothea Lasky.

KM: You’re the 2014-15 Writer-in-Residence at Western University. You’ve been very present on campus with various initiatives such as Flashbang—a speed-editing event and Reclaiming the Corridor of Excellence: A Public Performance in which you will be exhibiting curated works in the new Arts and Humanities building. What have you got planned for your second term?

GB: I plan to sleep in my office under a pelt made from actual Irving Layton. Unless it’s Naugahyde. And then, I’m doing a few readings including at the London Open Mic, another Flashbang event at the Weldon library which will involve text performance and music, and a multi-media event in conjunction with Josh Lambier’s Poetry Lab.

I’ll also do another Flashbang speed-editing event (like last time, with student-writer-in-residence Steven Slowka), and some kind of live performance as part of the Corridor of Excellence project, though I haven’t figured out exactly what yet. As part of the London Public library part of the residency, I’ll also be doing a speed-editing event there, and workshops for seniors, for street-involved youth, and at the London Writers Group. This is in addition to visiting various classes and holding individual consultations during non-Layton-coated office hours.

KM: What is your favourite or funniest literary moment, if you have one?

GB: When one of my sons was about three (N.B. Ryan: don’t worry I won’t say which son), I took him with me to a reading that I was giving. As I went up to the podium and opened my mouth to read, he ran up, grabbed all of my papers and threw them across the room. Then he exclaimed, “No. I am the writer!” After I gathered my papers, I began to read again. Then he squatted in the corner and shouted, “I HAVE TO POO!” I actually thought the whole thing was quite funny. Why? Was it my Dadaist-Fluxus-anarchist son destabilizing the conventions of the bourgeois reading via a Freudian intervention, or just whacky madness that reminded me not to take things so seriously? Either way, the mostly university-age non-parents were pretty shocked, though the parents thought, “Oh yes, just another Thursday night.” I didn’t bring my son along to another reading until he was much older. Now he’s a musician in Toronto, but I haven’t staged a similar intervention during one of his performances … yet … my son and I have performed together quite a lot in a variety of situations, both literary and musical.

And then there was that time that I was driving across the border to read in Buffalo and the border guard, on hearing that I was a poet, read me her (really awful) poetry for ten minutes as the cars lined up for miles behind me.

Thanks very much for the questions. I really appreciate it.

For our London, Ontario readers who would like to make an appointment with Gary Barwin at Western (between now and April 2015) contact Vivian Fogloton in the Department of English and Writing Studies.

GARY BARWIN'S MOST RECENT POETRY BOOK

MOON BABOON CANOE

MANSFIELD PRESS, A STUART ROSS BOOK. 2014

A follow-up to his acclaimed The Porcupinity of the Stars, Moon Baboon Canoe is filled with Gary Barwin’s trademark humour, invention, musicality and craft. These witty and surprising poems confront subjects as diverse as time machines, elves, hummingbirds, birth and cows, yet manage to explore the perennial themes of poetry: delight, mortality, childhood, love, the natural world and squirrels. It is a moon-guided, baboon-paddled canoe of a book, and around each bend in the river we find the sources of our strength: consolation, goofiness and joy.

Kathryn Mockler is the publisher of The Rusty Toque.

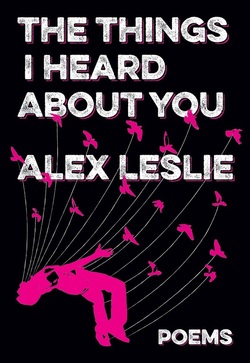

RUSTY TALK WITH ALEX LESLIE

Photo by Lorraine Weir

Photo by Lorraine Weir Alex Leslie: In kindergarten, there was an assignment to write a riddle. For whatever reason, this assignment became a kind of obsession for me. I remember writing more than the required number of riddles and then having to choose between the riddles. This was a Sophie’s Choice situation for five-year-old me. One riddle I wrote was “What travels all over the world but is always in the same place under foot?” I was very adamant that underfoot was different than under foot and I remember the arguments from my classmates that I was “cheating” and that this was “unfair.” It stays under your foot. The answer was the sole of your shoe. Apparently, the sound/word under foot could not be used in this tricky, ungrammatical way and I was a cheater. I have memories of hiding under a table.

One other riddle involved a gun; I don’t remember the riddle, just that it involved a gun and that this was “disturbing” and that this riddle was quickly disqualified by the teacher. No weapons; no messing with portmanteaus.

After this, I began to write stories about our neighbours as caricatures, for example “Liora the Witch.” I had no mercy. I also was convinced that I was the most hilarious person on the planet, which helped. Then I wrote longer and longer things, all fiction. I was always working on writing projects through elementary and high school. But thinking back, the riddles were the beginning. I was going to write the best riddle. I just wanted to write a really hard riddle so that I could have the opportunity to tell everybody about my clever word game. I do not recommend this social strategy to today’s kindergarten students. The world needs you to survive.

SJS: What is your writing process like? (How often do you write? Where? When? Etc.)

AL: My life is currently deeply split between graduate school and my writing practice. My degree is not in an artistic or literary field, so there is some measure of separation there, which is good. My writing process is that I write things in series, to sustain momentum and motivation; writing things in series is very helpful when there are other forces in your life. It gives you a thread to hold onto through everything else. I carry around a notebook that I write helpful ideas and phrases in. I also tend to write myself emails on my iPhone, so I receive lots of emails about scenes and phrases from the Gmail sender “me.” Me sends me lots of cryptic random stuff. If “me” were not me I would be concerned. When a piece reaches a certain stage, I print it out and carry around a copy that I mark up with notes. I only work well when my process is very organic and disorganized and I have succumbed to the fact that this is just how it goes and eventually I get somewhere without really noticing.

I don’t have a specific time of day when I write; late at night works and in the summer I often wrote in the morning, when I didn’t have classes (but who are these schedule-less writers who can write all the time at their ideal time?). I do have a workspace in my home, which helps. I would like to add that other writers are part of my process. I’ve been workshopping with poet Adrienne Gruber for several years. Her next book is out with BookThug and her chapbook Intertidal Zones is just out with Jack Pine.

SJS: How do you approach revision?

AL: Revision is my favourite part. I print it all out. I carry it around and cross things out. I write things in. I prune. I fiddle. It is like having a bonsai tree in your backpack that only you can see. I obsess. I remember reading an interview with Michael Ondaatje (whose early experimental fiction such as Coming Through Slaughter is very important to me) that writing a novel is like building an imaginary city in your backyard. Yes, that’s what it’s like. Revision is great but there is a sense of loss when the book is done. Then you go on to the next thing.

SJS: When you started writing your latest book, The things I heard about you, did you write each poem with the intention of making it into a collection or did it happen more arbitrarily?

AL: This project began because of the line “I know how small a poem can be” by John Thompson from Stilt Jack. At that point, maybe three or four years ago, I was struggling with the short fiction form—the need to “conclude” and have an “arc” and what I can see now as the usual post-first-book anxiety about the form that created you—and the phrase “I know how small a story can be” came to mind. It took me a while to arrive at how to begin this process but I started to write vignettes or prose poems around certain intense experiences/events/scenes; these pieces were based on photographs. I then did a “blackout” process whereby I wrote increasingly “smaller” versions of these pieces of text. So the method always was what connected the pieces in my mind. No, I didn’t intend to make a collection of these pieces. It was a project that interested me on a technical level as a writer of stories/poems/cross-genre things. I wrote these pieces until the process lost its purpose or interest for me. The technical process of literally breaking down texts helped me to find language in my descriptions that I hadn’t been aware of, to become more aware of my own rhythms of writing, and to uncover connections in the pieces that I hadn’t seen before. This process taught me a lot about myself as a writer.

SJS: The poems seem to deal with a monumental sense of loss juxtaposed with a sense of freedom and hope. How did these themes, or others, influence the stylistic decisions for the book?

AL: Thank you for that reading. I didn’t consciously choose those themes for the book. I think that many of the pieces explore space in a layered way, in particular the coast and the structure allowed me to reflect different aspects of environments. I would also say that relationship is a theme in the book; there are several pieces about taking apart another person, or considering the different parts of them. I do think that the pieces that deal with loss, in particular grief, move to a place of release (the word I would swap in for “hope”) partly through the structure, because the structure demands that the original text shrinks, has the heavier parts lessened, discovers the more concentrated parts of itself. I’m glad that produced a sense of freedom or hope in your reading.

SJS: How did you approach the poems as a collection? Did you mean for them to have a narrative or was it purely coincidental?

AL: In the end, I ordered the pieces for pacing, both in terms of more intense pieces being spaced out. I am curious what narrative you found in the pieces overall? Do you mean a story narrative? Or a narrative created by the evolving form of the pieces?

SJS: The narrative I am referring to is definitely emphasized by the evolving form of each piece (which is actually quite beautiful, I might add). I think perhaps the kind of narrative I am talking about is more of an "emotional narrative" that runs through the book. In my interpretation, it is this back and forth between things, or people, that are lost and found. Where do these ideas come from? What inspired you to write these poems?

AL: I like that idea that it is a movement between things that are "lost and found," because I like to read the poems as fluid components rather than being something static, like different steps on a staircase. Several of the poems that centre around loss do speak out of losses in my life over the past five years. In particular, the piece in the collection "Knockin On Heaven's Door" is about the intense, initial period of grief and the (I think common) coping strategy of immersing oneself in music, placing technology as a barrier between oneself and the world during a time of grief. The way that the structure of the poems, moving from large or "monumental" as you put it to small or specific or minute for me mirrors in a way how this can be the experience of loss or grief—that there is something huge/intangible/incomprehensible but in the end what we remember is the specific sound, place or detail. I think that remembering detail is a way that we cling to our experiences; it was *this specific* shade of colour, it was *this specific* kind of laugh*, it was cold out, it was a Tuesday. Once I described this project to a friend and she said, "Oh, I don't think those are miniatures, those are needle biopsies" and I found that very apt. It can be a painful process to extract or uncover.

SJS: In the notes and acknowledgments section of the book, you mention that there was a last minute title change from I know how small a story can be to The things I heard about you? What prompted this change?

AL:

(a) I know how small a story can be is a cumbersome title

(b) I was embarrassed by how self-important it sounds

(c) Smug?

(d) Sometimes a title is the name of the Microsoft Word Document you made and it isn’t actually the title of your book. It is important to know the difference.

(e) A title can take you through a process as a touchstone for your process, but you need to move on from it when you need to, like a name that doesn’t fit you anymore.

SJS: What are you working on now?

AL: How to stay balanced while a full-time grad student and a writer.

How to not be overtaken by institutional environments.

I’m working on two projects.

My collection of stories People Who Disappear was published by Freehand a couple years ago and I’ve been working on short stories since then. One, “Stories Like Birds,” you can read online at Lemon Hound. Another, “The Sandwich Artist,” will be in Prairie Fire soon. The collection is coming together. It’s called We All Have To Eat. Stories take me a long time.

I’m also working on a collection of prose poems/experimental prose pieces called Vancouver For Beginners. These are pieces that look at Vancouver, my hometown, from many fractal perspectives. It’s inspired by texts like Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino and feria by Oana Avasilichioaei in terms of how they approach the city as an imagined space. Some pieces from that project have been in EVENT, The Capilano Review, filling station’s issue devoted to experimental writing by Canadian women, Dreamland, and Descant. A piece from the project will be in Best Canadian Poetry In English 2014, edited by Sonnet L’Abbee, with Tightrope Books, an anthology I’m proud to be part of. It’s out in November.

I’m also working on another fiction project that at this point is mostly research; that one will take a very long time.

ALEX LESLIE'S MOST RECENT BOOK

THE THINGS I HEARD ABOUT YOU

NIGHTWOOD EDITIONS, 2014

Shortlisted for the 2014 Robert Kroetsch award for innovative poetry, The things I heard about you is an exploration of precision and the unspoken, executing a process whereby vignettes and scenes break apart into fragments, rumours or suggestions of the original story. When stories decompose or self-destruct, the results vary, producing an effect of texture and syntactic transformation. This is a book of tidal memories and elegies, love songs to the coast and all its inhabitants. The things I heard about you is Alex Leslie’s debut poetry collection.

"Prose poems, soundtracks, minifictions—the lyrical, multi-faceted pieces in The things I heard about you record the ways in which language makes and unmakes us. 'Between a tooth and safety,' bodies, weathers, genders inhabit and are inhabited by histories of loss, institutions of violence. These stories don't shrink even as they grow smaller; each is distilled to a potent drop that sinks into the mind like ink into skin: 'I, not here, write.'"

—JEN CURRIN

VANCOUVER LAUNCH

TORONTO LAUNCH

MONTREAL LAUNCH

Visit Alex Leslie's website here.

Check out Alex Leslie's poems in Issue 6 of The Rusty Toque.

Julie Bruck

Julie BruckPhoto by Kara Schleunes

RUSTY TALK WITH JULIE BRUCK

Tom Cull: What is your earliest memory of writing creatively?

Julie Bruck: When I was quite little I wrote a rhymed poem that began, "Nonsense is so many things,/ bats with hats and cats with wings." My mother made a huge fuss over it, but I wasn't as impressed. I never really felt engaged by writing as a kid. I preferred drawing, or being outside--preferably with live, rather than imaginary animals.

TC: As a child, did you read poetry? Was poetry a part of your childhood?

JB: Poetry was read aloud in our home, and valued. My mother wrote poems and studied with Irving Layton, and went on to publish her first chapbook in her mid-80's. My father liked to quote Ogden Nash and lyrics from Gilbert & Sullivan. There was a lot of word-play in the house. My two older brothers tortured me with names I didn't understand, like "perpetrator of arm-chair methods" or "petit bourgeois scum." Eventually, the dictionary became a survival tool.

TC: How did you become a writer?

JB: I wasn't drawn to writing until my early 20's. I was studying photography and art history and took a fiction workshop at Concordia University as an elective. My stories were awful, but that class woke me to the kinships between poetry and photography, especially how both were a matter of framing, and how crucial the placement of that frame could be. That fit with my way of seeing the world. I was really adrift at that time in my life, and I think that process offered an illusion of order. It also made my work too drum-tight and over-determined, but there would be time to work on that later.

TC: You were born and raised in Montreal but now live in San Francisco. How has this transplant affected your poetry?

JB: My relationship to home was always hyphenated, especially as an Anglo in Quebec, so being a Canadian in the U.S. felt oddly familiar. I think becoming a mother at 41 was the bigger shift, and certainly one that had an effect on my work. As a parent, it's harder to draw lines between what's personal and what transpires in the larger world. The traffic between those two realities figure in my writing.

TC: Your website describes you as both “poet and teacher.” Can you talk about the relationship between writing poetry and teaching poetry?

JB: Much of my teaching focuses on generating new work, and I emphasize the importance of surprise in the writing process, as well as during revision. The bold examples of my students help keep me honest. They are almost always receptive to trying new strategies and approaches. They remind me to practice what I preach, and I'm grateful for it.

TC: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process?

JB: While most first drafts come quickly and freely, I am glacially slow from that point on, and can spend years on a poem before it's either ready to leave the house, or be consigned to a dusty folder. Revision is crucial and I print every draft. I am not, alas, good for the forests. So often though, the most creative moments take place during re-writing, even years after the rush of a first draft. Sometimes, it takes that long just to step out of the poem's way. Those moments are worth waiting for. They're exhilarating.

TC: Do you have any advice for newer poets who struggle with evaluating feedback from their peers? When should a poet bend to critique and when should a poet stick to his or her guns?

JB: I think how you respond to input depends on temperament and experience, among other things, so it's hard to give boiler-plate advice. On the other hand, it can be very useful to soak up feedback from your mentors and peers (and from your reading) when you're "new" at poetry. Sure, the poem belongs to you, and no-one can "steal your voice" and you can always revert to your original version. Ultimately, though, the poem must also belong to the reader, and your colleagues can be great indicators of how and what that poem is communicating. Good readers can also keep you open to what the poem might be reaching for, even if that differs from the poem you set out to write. This can teach you to read your own words on the page, which might already have better plans for themselves..

TC: You have spoken elsewhere of your poetry being characterized as “accessible.” Is accessibility important to you as an artist? Is it something you strive for in your writing or is it just the way you write?

JB: Sometimes I regret using that word. Accessibility gets a bad rap, as if it suggests poems which suit the reading habits of a well-meaning duck. What I'm after in my work, and what I look for when I read, is clarity. I find that the clearer a thing is, the more mystery it possesses. I do not equate confusion with mystery.

TC: Confinement and threshold seem to be recurring themes in Monkey Ranch. Whether it be a Howler Monkey in a zoo cage, a race-horse (“a gleaming ton of coiled muscle”) standing ready at the gates, a shark in a sling being released into the ocean, or even the “liquefied sunlight” trapped between two doors of a vestibule, your poems seem to characterize people, animals, and things as either caught between and/or poised to break out. Do thresholds hold a particular significance in your poetry? Do you see your poetry as negotiating a relationship between confinement and freedom?

JB: What a terrific question! Someone else recently characterized my work as "the poetry of aftermath", but thresholds and the negotiations between confinement and freedom certainly resonate. There's a line in my first book, The Woman Downstairs, in which the speaker describes herself and her entourage as "always on the threshold of some promised definition." I think part of this interest in being on the verge has to do with an adolescent quality that I keep expecting to outgrow--the idea that we're all in a state of perpetual emergence, and that on the other side of that process, everything will be clear. Ha!

I think these cusps also reflect the tension between the (apparent) simplicity of innocence and the endless complications of knowledge. It's a tension that's so beautifully dramatized in Elizabeth Bishop's poetry, and your question helps me explain the abiding affection I have for her work. It's also a tension that's inherent in raising children, and in being with animals, since both are so vulnerable to the caprices of human adults. Finally, thresholds always signal some kind of change—that uneasy, and most interesting part of human affairs. Adrienne Rich said, "The moment of change is the only poem." That's a quote I carry in my head, and if I was 30 years younger, it might be a tattoo.

TC: Monkey Ranch is both the title of your book, and the title of one of the book’s more disquieting poems. The “monkey farm” in this poem is one of the many cages or prisons found in this collection. But the title also seems to be a play on “Monkey-Wrench,” a tool that derives its name from the nautical meaning of “monkey” as any provisional tool designed to suit an immediate purpose. To this connotation must be added “monkey” as meaning “mimic,” “mock” and “play around.” All of these meanings seem alive in this collection—often simultaneously. Can you say something about the choice of the title and how it works as a sign that marks the entrance to your poetry zoo?

JB: Monkey Ranch was my choice for the book's title, though my editor was resistant. She didn't feel that the poem was representative of the collection as a whole. She also thought the title, especially in concert with the crazy cover image, suggested a lighter book than I'd written. I could see her point. As a title poem, "Monkey Ranch" is more surreal than most of the other pieces, but I felt quite certain that it knit together various themes and impulses that ran through the book. Thematically, those included the caging you point to, creatures, family life, and the ways we often recall and talk about painful memories, but only selectively. As far as the word-play in the book title, you've nailed it! This was a tricky book to order and shape because of the variations in voice and tone from poem to poem. The potential wordplay in the title was intended to pick up a playful thread that also runs through the collection. My hope was that giving a slightly stretchy title to what is, at heart, one of the darkest pieces, would speak to what the book as a whole presents. I think you said it best: that all these meanings inhabit our monkey lives, "often simultaneously." Thanks! That's exactly what I was after.

TC: What are you currently working on?

JB: I'm writing new poems and just letting the drafts stack up. It will likely take another year before I start rearranging them into anything remotely bookish.

Monkey Ranch, Brick Books, 2012

Description from the publisher:

Winner of the 2012 Governor General’s Award for Poetry

Globe 100 Book for 2012

Shortlisted for Pat Lowther Memorial Award and CAA Award for Poetry 2013

Comic and sober by turns, these poems ask us what is sufficient, what will suffice?

… a mandrill, a middle-aged woman, a shattered Baghdad neighbourhood, a long marriage, even a spoon, grapple with this unanswerable conundrum—sometimes with rage, or plain persistence, sometimes with the furious joy of a dog who gets to ride with his head through a truck’s passenger window. Julie Bruck’s third book of poetry is a brilliant and unusual blend of pathos and play, of deep seriousness and wildly veering humour. Though Bruck “does not stammer when it’s time to speak up,” and “will not blink when it’s time to stare directly at the uncomfortable,” as Cornelius Eady says in his blurb for the book, “in Monkey Ranch she celebrates more than she sighs, and she smartly avoids the shallow trap of mere indignation by infusing her lines with bright, nimble turns, the small, yet indelible detail. Bruck sees everything we do; she just seems to see it wiser. Her poems sing and roil with everything complicated and joyous we human monkeys are.”

MONKEY RANCH

Our monkeys were striped

green and yellow, except

for the red and white ones.

Outside the house, a screaming

kaleidoscope of stripes chased

stripes, until they settled

in the branches at dusk,

to pick each other's nits.

Father tired of monkey

farming, took a job in town.

We starved our monkeys.

Day by day, they slowed,

and when I picture them now,

or dream of how it was,

they stagger in the black

and white of old newsreels.

It took them a whole year

to die off while we watched.

In those days, children did

as they were told, and Mother

always favored chinchillas.

But they used to wear such

cute little monkey hats--

red, white, yellow, and green.

THE CHANGE

So, I’ve done what my body was made for.

My eight-year-old is all legs, careening

down the basketball court, and I do

acknowledge the pulls and pushes of tides,

moons, of love and such, even if I stop short

at crystals and meet-the-plankton music.

My husband hums in the house,

my daughter sings while she plays.

I’m hunched at the kitchen table,

jaw clenched, staring down a blank

grocery list when that stringy mouse,

the one who holds keys to this place,

scrabbles across the awful linoleum

for the first time today and my shriek

is so sudden and muscular and primal

I know I’ve pulled something in my neck.

If this new Tin Cat™ does its job, I swear

I’ll carry the jumpy, humane contraption

straight to the park in my bathrobe,

calmly raise the metal lid and let

the mouse go with a kind, steady hand.

I’ll be better than I am,

pretend to love

this creature I'd rather drown.

What does it mean to love

the life we've been given?

RUSTY TALK WITH MATT RADER

Matt Rader

Matt RaderPhoto by Ron Pogue

Kerrie McNair: How did you first get into writing?

Matt Rader: That’s one of those questions of history I’m always tempted to rewrite. I probably have several times. I recall writing in school as a kid. And I recall writing poems with my mum when I was eight or nine. Then I wrote poems all through high school. I took writing classes at the University of Victoria from age 18-21. But I didn’t start seriously until the fall after I graduated from my undergrad. That fall I wrote a poem called “Exodus.” Later that poem became the first poem I published professionally in sub-Terrain magazine.

KM: What poets or writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now?

MR: In those earlier years after my time at UVic, I read Ted Hughes exhaustively. Then I read Seamus Heaney who remains a major influence. Michael Longley was my primary influence for more than half a decade. In the last few years Larry Levis has been hugely important, and most recently I have fallen in love with Mary Ruefle’s poems. Heaney, Longley, Levis, and Ruefle are all currently represented in the Jenga of books on my bedside table. I could also tell this story with Homer, Keats, Hardy, Yeats and Eliot. Or Bishop, Plath, Lowell, Gilbert, and Larkin. Not to mention Babstock, Solie, O’Meara, Thornton, and Bachinsky. The problem with any list like this is that I can’t help but make egregious and unforgivable omissions.

KM: You used to run a literary micro-press out of Vancouver for writers who were marginalized for a variety of reasons including age, content matter, sexuality and ethnicity. Can you describe how you got into literary/cultural activism and how it informs your writing? Are you working on any community projects at the moment?

MR: I was lucky enough to meet a set of young artists and writers, largely centred in Vancouver in the early aughts, who had a desire to share their work with each other. Many of us had grown up in the DIY music and zine culture. Several of us were involved in various queer communities. We were culture makers and pursued that right into our publishing deals and writers festival invitations.

I’ve been involved in several projects lately and there are few more in the works. A year ago I collaborated with my friend Grant Shilling to put on a community storytelling event. We live in a small mountain village on Vancouver Island. The foothills here have been ravaged over the last century and a quarter, first by coal mining and then later by logging. Currently the hills around our village are used both industrially for logging and recreationally as a major mountain biking destination. The event was called Bronco’s Perseverance: Changing Gears in Cumberland. Bronco’s Perseverance is the name of one of the main trails along Perseverance Creek. The trail is named after the long time Cumberland mayor, Bronco Moncrief. Our tagline was “Beer and bullshit.” It was amazing.

This past summer I collaborated with a local designer, Sarah Kerr, to create large poster-sized newspapers modeled on papers from the 1913 that we researched in the Cumberland Archives. There were six pages and they told the story of two young girls during the height of the Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike that was 100 years ago this summer. We put the posters up around town.

I wouldn’t say that my cultural activism informs my writing exactly, but I do think my writing is informed by the same impulses as my cultural activism. I can be didactic about it and try to make a case for aesthetic and moral value, for form and identity, for art as experience, but in the end, those impulses are as known and as mysterious to me as to anyone else.

KM: You’ve been involved in curating several reading series such as the Robson Reading Series. Do you have any advice for new poets or writers on reading their work for an audience?

MR: Read as slowly as you possibly can, then read a little bit slower. Always read less. I believe Mark Twain has a set of rules. Google Mark Twain’s rules.

KM: Can you describe the writing process for your most recent collections of poems, A Doctor Pedaled Her Bicycle over the River Arno, which your publisher describes as unraveling “our layered identities to explore the lyrical fabric of humanity”? Over what length of time were the poems written? Was there a particular catalyst for this project?

MR: The earliest poems in A Doctor were composed alongside the bulk of my previous collection Living Things and I was in the midst of composing the core poems in A Doctor when Living Things came out. All told, it probably took about three years to write.

I was pursuing several things in that book. One was a reintegration of narrative into the poems, something that I felt I’d written out of my poetry in Living Things.

Secondly, I was exploring cultural history in a way that I had explored ecocultures in Living Things. I was particularly looking at my family history on one hand, and the colonial and post-colonial history of coastal British Columbia on the other hand. It wasn’t really an either/or. These histories were more braided than that description suggests.

Thirdly, I had been thinking since Living Things about poetic form and tradition and in A Doctor that became expressed as custom and customs. I was intrigued by the idea that custom and customs (or costumes as Elizabeth Bishop would have it!) can be both the guarantor of civilization and a purveyor of horrific violence.

KM: Many of the poems such as “I Acknowledge: and “History” in A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle over the River Arno detail the lasting presence of history in contemporary life. How did the past motivate your desire to define the present when it came to writing these poems?

MR: John Dewey says “art celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reënforces the present and in which the future is a quickening of what now is.” I really like how he says, “what now is” instead of “what is now.” I know that I should be more generous and explain what I think this means, but I don’t want to. I tend to see everything relationally, which is to say with a kind of historicity.

KM: Conversely, poems like “Natural Lives” and “Homeowners Manual” address sentiments of devotion. Was it a conscious decision to, at some point, stop looking back?

MR: No. I never did stop looking back. Though I don’t think of the past as being “back there.” Looking at history is looking in the mirror. Looking in the mirror is looking at history.

KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one?

MR: When I was a small boy Dennis Lee came to my small island town and gave a reading for children. I remember the bookstore as having creaky old wooden planks for a floor. Everything seemed very dark. He picked me out of the crowd and sat me on his knee and began to recite a poem. To which I promptly ran away crying.

Then, nearly thirty years later, after the launch of my last book in Toronto, I walked out the party and standing in the street at the bottom of the stairs was Dennis Lee. He was holding my book!

I introduced myself and we said kind things to each other and then I told him the story I’ve just related here and he said … well, I can’t tell you what he said, not in print. But if I’m ever in your town you can buy me a beer and I’ll tell you the rest …

KM: What are you working on now?

MR: I have a collection of short stories that’s meant to come out next fall. I’m also working on a new book of poems with a kind of deep hermetic code. They’re largely elegiac. I’m also about to embark on a filmmaking project with a young filmmaker, called Jim Vanderhorst. I have a chapbook of poems coming out with Baseline Press at some point in 2014.

Enjoy an excerpt from Matt Rader's forthcoming chapbook from Baseline Press:

UNSPEAKABLE ACTS IN CARS

It’s the first day of summer and we’re so happy

To see the sun and the satchel of colours it schleps

All those dark kilometres. The sky is so blue

And the sea is blue and the small islands in the sea

Are blue also. How our sun must love blue.

We have beachgrass and bull kelp and lion’s mane

And we love them all because we love the sea

Which is cold and buoyant. Friends now of seasalt

And knotweed, the mountains know all about us

And who we are when we are most ourselves.

But their blue haughty distances are no help.

We are who we are with mock orange and wisteria.

We’ve nothing to bitch about. The high cirrus

Can’t touch us. We been alive just long enough.

originally published in The Fiddlehead 253

DOVE CREEK HALL (FORMERLY SWEDES' HALL)

The children play their fiddles so slowly I am sad

For the old wooden hall among the cow patties.

Who cut the rhodo blooms and set them on the piano?

They bow tiredly through every tune. Even the cows

Have wandered away from the music to the far side

Of the pasture. All the Swedes who built this hall

Are dead now and the women they married are dead

And the pastor who married them and their friends.

But the children do not know this or just how sad

Beauty is on the last day of spring with instruments

And young players making music beneath the rafters.

They play along with mistakes and embarrassment.

Tell me, who hung the hand-stitched stars on the wall?

Who hung the evening light from the windows?

originally published in Arc 67

A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno

House of Anansi Press, 2011

Description from publisher:

A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno carries within it all the technique, vision, imaginative labour, and razor-sharp precision of Matt Rader’s first two collections, Living Things and Miraculous Hours. But it also ascends to a new and luminous, demanding, particularized realm of the human.

Wildflowers and weeds, newspaper archives and illness, hostels and hostiles, parenting and the shadowy history of grandparents, war and Renaissance paintings: Matt Rader’s unassuming, deeply spirited, and expansive poems show us again how contemporary lyric can go such a long way toward revealing our true homes to us at the moment we find ourselves most nakedly un-housed. Rader seeks out limits, borders, and frontiers—those mapped for us by authority, and the concomitant, interior shadowlines we ourselves draw—in order to test their validity.

Marita Dachsel

Marita DachselPhoto by Nancy Lee

RUSTY TALK WITH MARITA DACHSEL

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively?

Marita Dachsel: My mother was an elementary school teacher, and grade one was her favourite to teach partially because she got to teach kids to read and write creatively. She did a great job instilling the importance of both in me, and I know I was writing creatively thanks to her long before my first true memory. When I was around five I wrote and illustrated a collection of stories about horses called…wait for it…Horse Stories. I remember spending longer on the illustrations than the stories, and I think the illustrations came first.

My parents’ living room is very gothic—red carpet, red velvet curtains, dark beams, huge heavy-glassed lights that look medieval in inspiration, a fireplace, and a menagerie of taxidermied animals and birds along one wall. But it’s the room that gets the most natural light. I remember writing one of the stories on the carpet, the sun warming my body, crayons beside me, the television on as it always was (I can’t remember the show, but Dukes of Hazard is my default childhood memory show). I was so proud of my work. I still have it.

KM: How did you become a writer?

MD: I always wrote. When I was in elementary school one of my goals was to be a writer when I grew up (along with fire fighter and architect, so take that for what it’s worth), and while I continued to write as I got older, it didn’t really seem like something that could be real.

Then I went to college with a vague idea that I might become and English professor. There I took my first creative writing class, amazed that this was possible. I loved it. My first published poem I wrote in that class. Then I learned you could do a degree in it at UBC, so I transferred and ended up doing both my BFA and MFA there. Despite this, being a writer feels both like something that I just happened to become and something that I’ve always been.

KM: What writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now?

MD: Just before I took that very first creative writing class, I was in a John Steinbeck and John Irving phase. Then I discovered Canadian writers and women writers. Reading Canlit felt revolutionary. Margaret Atwood, Barbara Gowdy, Carol Shields. Anything and everything in my Canlit anthology seemed to be a springboard.

Now, I don’t have enough time to read everything I want to read. So many novels, poetry collections, essays, short stories, memoirs I want to read. Right now, I’m reading Brenda Shaughnessy’s Our Andromeda, Steven Price’s Omens in the Year of the Ox, Amanda Leduc’s The Miracles of Ordinary Men, Ann the Word: The Story of Ann Lee, and what feels like a million various poems and anthologies for the poetry class I’m teaching on poetic forms this fall. I’ve been itching to start Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, but I’m going to wait for the right weekend to devour it.

KM: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process?

MD: My process for poetry varies a lot depending on the poem, what was its initial impulse, where it came from. I scribble lines in a notebook, return days, months later and build off a line or an image. Then cut, slash, and rebuild.

With the poems in Glossolalia, so much was dependant on finding the right voice and shape. I’d research, make notes, write a draft. If the voice wasn’t right, I’d move on to the next wife. But if I felt like it was close, I’d start shaping the poem, writing more and more, then hack it to pieces, rewrite, hack, rewrite until it all sounded and looked right. Then I’d come back to it in a year or two. If it still felt right, great. If not, back to the beginning of the processes.

KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one?

MD: When my eldest was a baby, I read him Oliver Jeffer’s Lost and Found many times a day. It was a family favourite and when I got to the part where [spoiler!] the penguin and the boy are reunited, I would hug my son and say “A big hug for the penguin, a big hug for the boy, a big hug for you.” One day when he was about 18 months, he was “reading” the book by himself on the floor of our living room. I spied him from the kitchen. He turned to the hugging page and he hugged the book. It still makes me a little misty remembering that moment.

KM: Your second poetry collection Glossolalia, is a series of monologues spoken by the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith. How did you come to the premise of this book and what drew you to the subject matter?

MD: I’ve always been interested in fringe religions, and a few years ago the FLDS in Bountiful, BC was in the news. I was curious about their tenet of polygamy and discovered that it was first introduced into the Mormon Church (of which the FLDS are a breakaway sect) by their founder Joseph Smith way back in the 1840s. I wondered about the women, how they must have reacted when faced with a concept so alien to the society in which they lived, to the culture in which they were raised. I wondered how I would have reacted.

I love research and can get obsessed about a subject quite easily. I found two great biographies on Smith’s wives: In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith by Todd Compton and Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith by Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery. I started reading them, responding with poems. The material is very rich—sex, religion, power, gossip, motherhood, sisterhood, jealousy. Juicy stuff.

KM: You’ve managed to give each wife her own voice and an impression of her character sometimes with just a few words or a detail. An example of this are the final lines of Emma Hale Smith’s monologue: “What I know: not all eggshells are fragile. / Not all twigs snap.” This tells us so much about her and cycles back to the first line which I understand is an actual quote from Emma Hale Smith: “I did not ask for this life but accept it as my calling.” While this is a fictionalized account of Joseph Smith’s wives, how did your research come into play in terms of how you developed the voice of each wife and how you shaped the narrative of the collection?

MD: I devoured the biographies and once I realized that I wanted to write a poem for each wife, that this was going to be a book-length project instead of just a few poems, I knew that I needed to get them right. They needed to be distinct, and that would be hard as they were all had similar backgrounds, lived at the same time, in the same town, shared the same faith and husband. But of course, they were all very different from each other, and I hoped to capture that. For some polygamy was something they embraced, others railed against it, and for others it was barely mentioned. The narrative was organic; I never plotted out what moments I wanted to write about. At one point I read a book about Joseph Smith’s death mask. The mask never made it into the collection, but his death was there, from a few angles.

I’d read about the woman, make notes, try to hear her voice, write a draft, repeat as necessary. The first draft of the first poem I wrote for Glossolalia was Emma’s, but it took six years of rewriting her to get it right.

KM: Each poem in Glossolalia takes on a different shape and form. What informed your choices about typography, line breaks, stanza breaks, etc.?

MD: I believe form and content are intertwined, that they inform each other. Ultimately, it was simply a lot of rewriting, lots of playing on the page, reading aloud, and rewriting some more until it sounded and looked right.

KM: In many ways, the book is more about the diverse and complicated relationships that exist between women than about the Mormon religion, but has there been any response from the Mormon community to your book and/or did you have any concerns around this?

MD: There hasn’t been any direct response from the Mormon community, but I also haven’t searched it out yet, partly because I am a little scared to. I’m not Mormon, I did write about women in a community I don’t belong to, have no ties to. I am a little concerned at being called out for appropriation or being insensitive. Many of the wives have hundreds of progeny. What if there is an irate great-great-granddaughter? I shouldn’t be afraid (it’s poetry!), but part of me is nervous. I’d hate to have that kind of conflict.