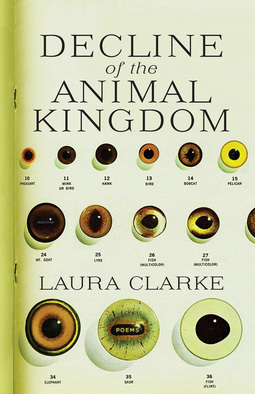

RUSTY TALK WITH LAURA CLARKE Laura Clarke. Photo credit: Katrina Afonso Laura Clarke. Photo credit: Katrina Afonso LAURA CLARKE'S work has appeared in a variety of publications including PRISM International, Grain, the National Post, and the Antigonish Review. She is the 2013 winner of the Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers from the Writers’ Trust of Canada. She lives in Toronto, Ontario. Between the ages of 10 and 30 I went from an egg to a killer whale. Myra Boom: Animals appear under multiple guises in Decline of the Animal Kingdom. What attracts you to them, in life and in poetry? Laura Clarke: Literature across cultures has a strong fascination with animals. Fables always feature animals. Children’s books always feature animals. I see this book as being a bit in the realm of fable. It’s a fable about hating your life and your job. [Laughs] I liked the idea of animals teaching moral lessons and I kind of liked placing what I consider the amoral character of the mule into that context. The mule is a good nexus for exploring ideas of environmental devastation, the unsustainable buildup of cities, questions of extinction and extirpation, excessive consumerism, and how that’s all encompassed in a character that cares about it but isn’t doing too much about it. I also think we use animals as a symbol to connect with other people, and to further probe the depths of our empathy in a way that we’re not comfortable doing with other people: the way that we sit at work and watch animal Youtube videos instead of talking to the people around us; the way that we will sit in a group of people and pet a dog rather than touch another human being or talk to another human being; the way that any children’s stories use animal characters rather than human characters because that’s more palpable. MB: I want to ask you about the title of the collection, Decline of the Animal Kingdom. As I see it, there are two distinct interpretations: either we humans are in decline, or else our impositions on animals are causing them to decline. What or who do you think is in decline? LC: I think it’s both. What they have in common is a struggle to understand captivity and how it relates to notions of freedom and responsibility, as well as the collapsing categories of domestication and conservation. That’s why animals are encroaching on our space or being encroached on in my poems—however you see it. Many of my poems are about the idea of extinction and extirpation: the horror, but also the complicated beauty of that. So many of our moments of beauty as humans are derived from the spectacle of animals and wildlife. The title Decline of the Animal Kingdom also refers to a scientific phenomenon: it’s a reference to the potential decline of the original classification system of animals. Most of us growing up were familiar with the Five Kingdom system of classification. It’s a very hierarchical structure, with humans at the top and smaller natural beings like fungi way down at the bottom. There’s another classification system, proposed in the ‘90s and based on molecular evidence, called a Three Domain system, where animals are lumped in with bacteria. Humans and animals and bacteria are all in the same category, and then the two other categories are just other life forms that are so much more numerous than us, but which we can’t necessarily see with the human eye. I’m interested in how that classification system changes our understandings of empathy: it’s about viewing animal life and human life as more intertwined. MB: Many of the poems have epigraphs excerpted from various sources: a manual on bear safety in Algonquin park, a resource guide from the Canadian Donkey & Mule Association. How did your research inform your writing? LC: The research part is huge for me. I did an interview with Karen Solie for the National Post recently, and I was asking her about research. She was talking about how less than 10% of what she researches and condenses makes it into the book, so probably, like, 8%. You do all this research into absurd things: in my case, that meant going on hunting message boards and reading natural history encyclopedias, and reading books about animal rights and animal morality. Most of that isn’t in there explicitly, which is why I don’t have bibliography, per se. But, as Solie said, research creates an atmosphere and a tone, and I think that was certainly the case for this book. All you can do is hope to pull out the tone, the language, and the feeling of all the different research that you do. MB: Talk to me about the “Dead Mule Poems.” You state in the endnotes that you took the titular modes of death (“Falls from cliffs,” “Rabies,” “Overwork,” etc.) from an academic essay on dead mules in southern Literature. How are these modes of death repurposed in your collection? LC: They all came from Jerry Leath Mills’s article, “The Dead Mule Rides Again.” I took them all exactly as he wrote them, so the poeticism of the titles, that’s him. I was really inspired by his titles, and they really opened up my imagination. MB: For example, “Dead Mule Zone IV: Overwork” is a dialogue between a mule and a “supervisor” that blends animal and human in its depiction of workplace drudgery: “Supervisor: .Why is the mule a fitting mascot for the contemporary alienated employee? LC: I think there’s a definite conflation of working class or manual labour and white collar going on. It’s tricky but it was deliberate. I’m from Hamilton and I’m from a working-class background, so I feel connected to that world. I’ve mostly done low-paying office work as an adult, so I was interested in how the two types of work are similar: alienated subjectivity happens to people who do manual labour as well as people who work in an office; injuries even happen to both people, like repetitive strain injuries. There are a lot of animals you could choose to represent a certain base instinct, but a mule seemed like a good choice, especially because what we know about them is so focused on the idea of “hybrid vigour.” They’re supposed to be superior to a horse and a donkey, and at the same time, we focus on their inability to reproduce. Also, combining a horse, which is super strong and a highly romanticized figure in literature, and a donkey, which is probably what I understand to be the horniest animal on the planet, and placing them into a context of constraint and restraint, is meant to yield absurdity. And I think those absurdities are definitely supposed to reflect someone in that situation. Not to say that office work is always unrewarding, because it’s not; sometimes it’s great. Still, the idea of fitting yourself into a certain position and reigning in your base desires, which we all have to do every day when we leave the house, is built into the figure of the mule, which is known simultaneously for all these things: a mule is stubborn, but it’s also the best at its job. A mule is an example of hybrid vigour, but it’s sterile. It encompasses a lot of contradictions. MB: Your poem “Messianic Age” is structured as a Craiglist “Missed Connections” posting and addressed to the deer that wandered into Toronto’s downtown core in 2009. In this particular poem, how does the form relate to your understanding of that event? LC: It’s funny, that’s probably the only poem that remains from my original manuscript, which I wrote and then gradually kept writing until it turned into a totally different manuscript; so that was probably 60-70 pages of poems, and this is the only poem from that. And it was maybe my first kernel of an idea, and then that got pulled along. It’s a “missed connection” because the deer didn’t see me. It speaks to the spectacle of animals. It’s linked to the experience of a zoo or museum, and the greater philosophical concept of looking at animals, whether alive or dead. It also connects with the commodification of animals in the products that we buy, whether they’re made out of animals, made for animals, or covered in images of animals. John Berger calls animals “objects of our ever-extending knowledge in his essay “Why Look at Animals?” and I try to engage with that concept while also playing with the potential for agency. MB: Do you have a favourite poem in the collection? LC: My sentimental favourite is “If I Were a Killer Whale.” I feel like it best encompasses my obsession with animals and raw feminist rage in one small poem. And it has lots of swear words in it, so if I have to do a reading, it gets me into character. The character of the killer whale. MB: What is your first memory of writing creatively? LC: My first memory of doing that is probably in grade 3 or 4, when we had to write one of those stories from the perspective of an inanimate object. Mine was from the perspective of an egg. Before that most of my writing had been very directly ripped off of the Babysitter’s Club or The Saddle Club or Sweet Valley Twins, so, like, “Jessica’s beautiful breeches,” “Shauna’s hair in the sun,” or descriptions of their horses, without any concept of interiority or depth or empathy. And I think because I was finally asked to consider the concepts of interiority and empathy, as a student who wanted to try really hard, I tried really hard, and then I had that moment where I realized what writing could be. I guess it’s kind of a precursor to this book, because I was pretending to be an egg, and now I’m pretending to be all the animals. MB: You hatched! LC: I graduated all the way to a killer whale. Between the ages of 10 and 30 I went from an egg to a killer whale. MB: You ascended the animal kingdom! LC: Exactly. I think my teacher would be proud. MB: Who are your literary influences, and who are you reading right now? LC: Right now I’m reading two of the new McClelland & Stewart poetry books, Liz Howard’s Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent and Madhur Anand’s Index for Predicting Catastrophes. I just went to a cottage on a writing retreat and I was supposed to be writing but I didn’t write, I just read. I read two Annie Dillard books; I reread The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson; and another Maggie Nelson book, The Art of Cruelty. I’m also reading my friend Jon [Chan Simpson]’s book Chinkstar (Coach House Books). Karen Solie and Suzanne Buffam were both my mentors at Banff, and I’m a big fan of their writing. Other influences are Anne Carson, CD Wright, Dionne Brand, and Mary Ruefle. MB: What did winning the Bronwen Wallace Award do for your self-esteem and your career? LC: Rather immediately, and relevant to this book, it let me quit my job, which I hated so badly that I was writing this book about it. It gave me a little cushion, obviously not to be able to live off of writing poetry, but enough to find another job that I liked better and to focus time and energy on putting together my manuscript. I also met a lot of other talented writers and passionate advocates of the arts, and it got me interested in a lot of peoples’ work. I love the Writers’ Trust as an organization: they tirelessly advocate for literature in all sorts of ways, and they have a real understanding of what an incredible impact even a small amount of financial assistance can have for a writer. At the other end of the spectrum, I’m careful not to place too much importance on awards culture or prize culture. Prize culture serves a particular function within literary institutions, and the work it does is good: it introduces wider audiences to different writers. But it’s only one measure by which we should choose to read or not read work. LAURA CLARKE'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed