I reviewed Gwen Benaway’s poetry collection Passage, which was published recently in Arc Poetry Magazine’s Canada 150 Reconciliation issue. The review started with a reference to Neal McLeod’s book, Indigenous Poetics in Canada. After the publication of the issue, I posted a photo of the review on Twitter. The photo led to a Twitter conversation with Gwen where she informed me of the problem that lay in invoking McLeod in a review of her work, given his history of domestic abuse of Indigenous women. The news of his abuse had broken publicly a few days before I posted the photo on Twitter, while it had been common knowledge within the Indigenous community. While I acknowledged the news as something recent and something that I had been unaware of, I also began to defend the review itself. Instead of being a productive conversation, the conversation became a disagreement. Doyali Islam, the reviews editor for that particular issue, stepped into the conversation, but the conversation ended without any resolution . The next day, after I had a chance to reflect on the Twitter interaction and the actual issues raised by Benaway, I reached out to her via email with an apology. Over email, we were able to unpack the problems raised by the presence of McLeod’s name in the review. The following interview rose out of that initial email conversation. Benaway and I met in downtown St. Catharines during Queer Canada, and over lunch, unpacked some vital issues plaguing CanLit in relation to Indigeneity, today. – Sanchari Sur Sanchari Sur: I was going to start with our online interaction and your reaction to the review. I want to contextualize the interview within that conversation and move forward from there. You can start by addressing how my use of McLeod’s name, as well as my ignorance about McLeod, was problematic, and why that affected you. Gwen Benaway: I reacted to the presence of Neal McLeod’s name in a review of my work because my work is situated in femininity, and situated in a response to forms of violence against female bodies, that having the name and intellectual and literary work of an abuser referenced in the context of my work felt like a kind of violence again against my work. My personal links to both Neal and the women that he impacted, which extends on multiple levels for me, was something that forced me I guess, in the context of seeing his work in the review, to have to reengage those kinds of narratives and memories that I have. It felt like a kind of a specific violence that emerged from a lack of knowledge around Indigenous peoples and community. [Within Indigenous community,] Neal’s relationship to women had been known for a very long time and was openly talked and spoken about, and the challenges and issues around his work as well as his own relationship were well known. Most of us had started to avoid and dissociate ourselves and our work from Neal’s work as a response to that. I think a member of the Indigenous community would have had that knowledge, would have come in with that awareness, and that understanding. It’s not a critique of you or your own positionality within that, but it’s epidemic of the ways that Indigenous work is often taken up by non-Indigenous audiences in ways that don’t understand the context that the work is emerging out of, and can’t truly appreciate or understand the intersections that are happening. And often without meaning to, render that work or interpret that work only in relation to [themselves], and can’t actually hold the work in its wholeness, and that is kind of a frustration. For me, having [one’s] poetry collection reviewed in Arc, as Canada’s premier poetry magazine has a kind of prestige in association to it, and is something that I wanted having been a reader of Arc for a long time, and when it happened, it happened in this context where – the review itself was fine – but [has] this predatory male presence sitting at the front, overshadowing everything. But also, my own need to then have to engage, and say, ‘But I don’t support Neal, but I stand with survivors, but my work is not reflective of Neal or his politics around Indigenous poetry but in fact in opposition to [it]’. SS: [Arc had] an Indigenous guest editor for that specific issue [and] I wonder if it had been somebody who was not a male Indigenous editor, would [they] have caught this? GB: I think that would have produced a change. I think older male Indigenous writers, particularly older male celebrated Indigenous writers, are often implicated in some of the kinds of gendered violence which have happened in our communities, and within the Indigenous literary community. But I think that there is also a certain sensitivity to Indigenous female writers and work, which we have developed with each other and through each other as Indigenous women writing, that doesn’t translate into Indigenous masculinity. And, an Indigenous woman of my generation connected to me in peership, I think it would have been different. Ultimately, the role of an editor is a complex one. It falls a lot on who is doing the review, who is editing that review, and who is placing that review. So, there’s layers of accountability within that, and also layers of community access and knowledge. So, I don’t know if having an overall issue editor who was female Indigenous would have produced systemic change. SS: Do you think that non-Indigenous writers should not at all attempt to review or – I mean, it would be problematic to say “engage” because if you are not engaging with the work, then what is the point. We should be engaging with the work to some extent. GB: I mean, I think it’s important for non-Indigenous folks to engage with [our] work. I also think it’s fine for non-Indigenous folks to review [our] work. But I know in my own writing practice, when I do reviews of works that emerge from communities that I don’t know and am not a part of, I reach out to members of that community, either to the individuals themselves or people who exist within my social network, who can let me know if I have missed something or if I am presenting that community in a way that’s wrong, or if I am missing the point, or if I am interpreting something from that text that I am seeing through my particular lens which doesn’t reflect how it would show up within the community. I think the work of being a good ethical reader and writer is addressing and seeing your own positionality, and trying as much as you can to reflect the positions of the community that you are speaking about. It may not always be perfect; in fact, it can’t be perfect. But I think it’s good that you show efforts of good faith and try to negotiate that process a little bit. SS: What I am hearing from you is this idea of listening, and to listen better, and to listen responsibly. Is there any other way that the non-Indigenous community could listen to Indigenous writers? GB: I think it’s good to engage Indigenous works, to listen to Indigenous people on social media and other platforms, to engage in those conversations. And, I think it is good to develop personal relationships. I think decolonization and the process of reconciliation occurs in the intimate relational space between people. As much as possible, I encourage non-Indigenous people to try and enter reciprocal relationships with Indigenous writers and Indigenous people that allow them to have some of those nuanced conversations. But I also wonder, when the news of Neal broke, when it became public knowledge, before the [Arc] print publication – a helpful strategy would have been to reach out to me and say, ‘Hey, I referenced Neal in this work and now I am aware of this other stuff, I am sorry about that.’ That simple relational gesture, I think, is reconciliatory. That kind of reparative work within a writing community, I think, goes a long way to build those kinds of relationship networks. SS: You are right. I should have done that instead of being defensive about it, and trying to defend so hard on Twitter, which is why I reached out to you. I am glad we are having this conversation. Obviously, I don’t want to repeat something like that in the future, and nor would I want somebody else in my position, perhaps another person of colour, who is not aware of the nuances, who has a difficult subject position themselves, [to repeat the same mistakes]. But I think by shutting down the Indigenous community, instead of engaging – therein lies a problem, therein lies the replication of exactly the kinds of systems we are trying to fight. We don’t want to be on opposite sides. We want to be on the same side. GB: And I think that’s a conversation to have around communities of colour and Indigenous people. I think it’s very hard for communities of colour to hear critiques around Indigeneity. I see a lot of defensiveness and anger and fragility, to be honest, emerge in those conversations. And, I think it’s useful for communities of colour to understand that spurring up with Indigenous communities doesn’t mean you are racist. It doesn’t discount your own experiences of racial oppression, and the knowledge you bring from your community and your specific colonial oppressions. But it’s important to not conflate that critique from Indigenous people with yourself. And I think that there is a tremendous amount of fragility built into being a racialized body in the world. We are constantly under attack, we are constantly proving ourselves. So, I think that when you get a critique from an Indigenous person, it is easy to be really wounded by that. But I think you have to fight through that woundedness to be able to say, ‘Wait, did I get this wrong? Maybe I did get this wrong. And, how do we work through this?’ SS: I think a part of the problem lies in the kind of privilege that is held by those who are not – say, for me, as a non-Indigenous person, I have a certain amount of privilege. I am also in academia, which adds more privilege to my position – so, there is a comfort in that privilege, a comfort in having that position of privilege, and not engaging with those who are in more oppressed positions. I think a lot of people don’t want to give up that privilege. In communities of colour – like you said, we are already under attack – we are trying so hard to protect what we have, that we forget that we might be harming other communities, unknowingly. GB: Yeah, and I think Indigeneity is one of those really complicated and nuanced things that functions often like race. But it’s different from race in a way that it presents itself in Canadian society, and that tension is a very complicated one. I think, there isn’t a lot of conversation visible between communities of colour and Indigenous communities, about ‘how do we participate in each other’s oppressions? How do we alter that? How do we build alliances that are meaningful?’ And, Indigenous people are often reduced to figurative representations. I have used this line before, we are the ghosts of Canada, and we often get reanimated by communities of colour and held up as performative land acknowledgements, but not have any actual relationship to Indigenous people in their life. I think there is a very complex and nuanced conversation that really needs to happen around ‘what is the relationship of communities of colour to Indigenous people in Canada, now and historically? And, how do we narrate those histories and realities, and build something from that?,’ where we are not just reacting to whiteness, but we are reacting to each other. SS: And, that kind of segues into a conversation about social media, as it was social media that started this conversation in the first place. At IFOA, you mentioned that social media is a space where Indigenous people come together, exchange ideas, and create community. How do you think social media has been instrumental in your own visibility? GB: Social media is really valuable for Indigenous people, and Native Twitter has proved itself to be a very powerful force, both for the critique and accountability in Canadian politics. What I see is Indigenous people who are coming from different nations, and landscapes, and geopolitical positions, intersecting through Twitter, and having a national dialogue around Indigeneity. And through that space [of social media], we find a lot of empowerment. And that’s why we default to it. And that’s why it’s a space where we are able to create in one of the few ways that almost never happens in Canada. Like, literally, a multi-nation Indigenous space where we are all there, speaking, interacting, and talking. And through Twitter, because of its ability to ‘mute,’ it can actually be a space where it’s just us. We support each other, we jump into conversations, we retweet each other. We are able to engage in community building in community solidarity, which we don’t get to do anywhere else. It is a really valuable space for me, and I think it’s our default way of communicating. I kept getting feedback from you and the Arc [reviews] editor [for that issue] that Twitter is not the best place to have conversations. I found that really interesting because for us, as Native people, Twitter is the best place to have conversations. And for me, as a trans woman, it’s a protected space, because I have control and access and agency around what I say and what is said to me, whereas, I don’t have that in interpersonal interactions. In some ways, I want to problematize that idea that social media is somehow reductionist and limiting in conversations. I think [social media] actually opens up a lot of space and safety which Indigenous people, or trans people, don’t actually have in everyday life. SS: That’s interesting, because for somebody like me, I am the kind of person who is not very good at having conversations on the go. I mean, person-to-person, it’s different because there are other cues happening, but something like Twitter is like texting. It’s hard for me to convey tone, for example, or to convey where I stand. Sometimes, I assume the other person will understand what I am saying, but some things get lost in translation. And that’s why I said, let’s have a longer conversation, which email allowed me. I could sit down, get my thoughts together. But I understand what you are saying. [Social media] doesn’t have to work like the same kind of space for everybody. GB: And it also builds in accountability. If you say something [racist or transphobic] on Twitter, there is a built in accountability around it. So, it creates a protection. For me, violence which is brought to bear on me or my body as a trans or an Indigenous subject, there is a record, and a way to speak back to it. For other forms of communication, I worry if that record exists, if there is a way to actually feel safe in having those conversations around Indigeneity. SS: I agree, but I have also heard this critique from other people, that Twitter is a space, or social media in general is a space, where people in CanLit who are very vocal are performing by being reactive. Do you want to speak to that kind of a critique? GB: I think that critique misses the point. Because we are social beings, we exist in social spaces. So, every act is performative, whether that’s in conversation, or via email, or in relational spaces. Sure, you can make the critique that there is a kind of activist and social performativity happening in CanLit spaces. I feel that is absolutely true, and probably doesn’t reflect a genuine engagement with important issues. But I would question that and say that you can actually ascertain if those vocal people being critiqued are actually “performing” that kind of performance. They might actually be honestly engaging – like in my case – with issues in a venue and format that’s safe for them. Sure, everyone is performing and you can say some performances are problematic cause of the way they are situated or who their intended audience is, but I think you can make that critique in any space. SS: At your Queer Canada keynote yesterday, you talked about the precarious position of being both Indigenous and queer. Have you ever considered the “precarious position” perhaps as a space of resistance? [Here, I specifically refer to Sara Ahmed and her mobilizing space of unhappiness as a space of empowerment for feminist killjoys]. Is it possible for this unhappy precarious place to be something else? GB: I understand [Sara Ahmed’s position] but I return to the notion of Indigenous wholeness, where I don’t want our happiness to be complicated. [Laughs]. I want our happiness to be straightforward. What does Native joy look like? What does Indigenous joy look like? And, can we return to that? And, can we return to the conversation about how we hold each other, and stand within ourselves as Indigenous people without having to negotiate or mediate ourselves through the history of violence against our bodies? How do we reconnect and reanimate ourselves without having to rely on outside forces? That kind of emotional, spiritual sovereignty is what, I think, our ancestors envisioned, and what I understand of Anishinaabe world view, and what our inheritance is. And, I want to see a return to that, to not a complicated happiness, but to an uncomplicated joy. It may not be possible but I think we must strive towards [it]. And that means to me, rejecting things like queerness, which to me, as you have articulated, will always be a complicated happiness. SS: At the Bechdel Tested Panel at IFOA, you mentioned that as an Indigenous person, you don’t see yourself as a part of Canada. But at the same time, your works exists within what is known as CanLit or Canadian literature. So, in that sense, do you think your own positionality is different from the way your work is being positioned within the conversation of Canadian identity? GB: I would posit that Canadian literature, or CanLit, is more than a practical reality. I would argue that it’s an ideological space, and an idealist space as well. So, I think while my work [is] practically considered part of CanLit work – it’s published by a Canadian publisher, it’s sold in Canadian stores, I attend Canadian events and speak to Canadian audiences – I think my work doesn’t ideologically enter the space I consider CanLit. And I think that ideological space of CanLit which I think my work falls outside of – and other Indigenous writers, and I would argue some racialized writers as well – is the ideological space of creating Canadianness, of multiculturalism, and diversity, and Canadian markers, and nationalism embedded within our work. I think we fall out of that ideological project. I think we fall out of social spaces as well. Indigenous and racialized writers are often used by CanLit as tokens, as representative members of our communities, to prove a kind of diversity, or as entertainment, to show up as exciting and different stories of worlds and cultures that they don’t understand. But that is not true inclusion. We are not actually part of CanLit. I would problematize the framing around the ideology of CanLit, and the practicality of CanLit, but not part of it as an ideological construct. So, I don’t see my work as being Canadian. I do see my work as being Anishinaabe. I do see my work as being Metis. And, I do see my work as being transsexual. But I do not see my work as being Canadian. SS: You know, how Nick Mount’s Arrival, a book about early Canadian writers, was published recently, and there are no Indigenous writers at all included in that book. It is ironic because Indigenous writers have always been excluded from the framing and making of CanLit, so then, why should Indigenous writers even want to be a part of the canon of CanLit. And, that exclusion is still happening now, as the writer of that book is also a professor at a prestigious Canadian university. All of this goes back to Neal McLeod being published by a university press, and his book being on comprehensive exam lists for doctoral students. All of this highlights the underlying problem that lies in the construction of CanLit; that is, which books get published and circulated. I am glad for the suggestions you have made in place of McLeod’s book [in your email to me], like Katherena Vermette’s North End Love Songs (2012),Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style (2017), and Daniel Heath Justice’s forthcoming book from Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (2018). A final question would be about your forthcoming work with BookThug. What kind of work is it? GB: Holy Wild is a collection of poetry that really tracks the first year of my transition. And there [are] two kinds of threads in it. There is a thread where I am talking about the physical, emotional, and social experience of transitioning, and drawing connections between being trans and being Indigenous, the relationships I see between Indigenous worldviews and trans embodiments, and how those are linked and connected for me, and really documenting the social and emotional landscape of going through that change, and its implications on me. [The collection also] traces two relationships with white cis men. So, half of the collection is sort of a doomed love story, and through that conversation, it begins to explore trans intimacy, the relationship between Indigeneity, whiteness, and white masculinity, and how those intersections impact you as a person as you go through that. SS: So, it’s more like the essay in The New Quarterly, “Trans Girl in Love,” and the stuff about vulnerability that you wrote about? GB: Yeah, it’s more of that for sure. GWEN BENAWAY |

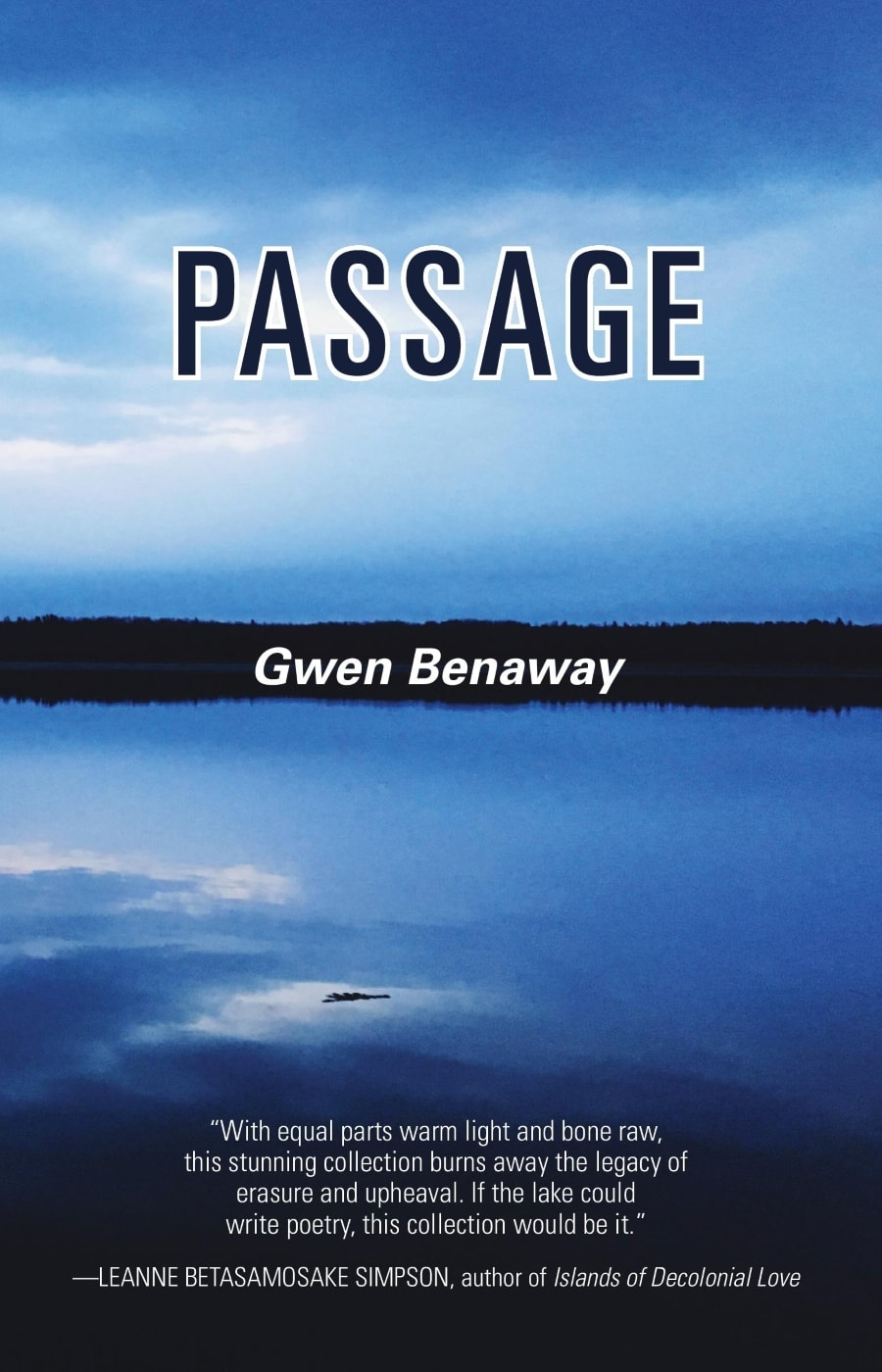

| Description from the publisher: In her second collection of poetry, Passage, Gwen Benaway examines what it means to experience violence and speaks to the burden of survival. Traveling to Northern Ontario and across the Great Lakes, Passage is a poetic voyage through divorce, family violence, legacy of colonization, and the affirmation of a new sexuality and gender. Previously published as a man, Passage is the poet’s first collection written as a transwoman. Striking and raw in sparse lines, the collection showcases a vital Two Spirited identity that transects borders of race, gender, and experience. In Passage, the poet seeks to reconcile herself to the land, the history of her ancestors, and her separation from her partner and family by invoking the beauty and power of her ancestral waterways. Building on the legacy of other ground-breaking Indigenous poets like Gregory Scofield and Queer poets like Tim Dlugos, Benaway’s work is deeply personal and devastating in sharp, clear lines. Passage is a book burning with a beautiful intensity and reveals Benaway as one of the most powerful emerging poets writing in Indigenous poetics today. |

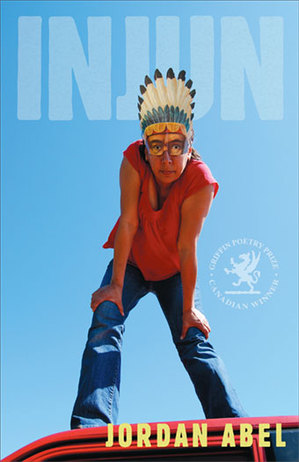

| Jordan Abel is a Nisga’a writer currently completing his PhD at Simon Fraser University, where he focuses on digital humanities and indigenous poetics. Abel’s conceptual writing engages with the representation of indigenous peoples in anthropology and popular culture. Abel’s first book, The Place of Scraps was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and won the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Abel’s second book, Un/inhabited was published in 2014. CBC Books named Abel one of 12 Young Writers to Watch (2015). His third book Injun won the 2017 Griffin Poetry Prize. |

I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization.

Jordan Abel: When I think about where poetry fits in, I’d have to say I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization.

SB: What about poetry do you find valuable in helping to destabilize the architecture of colonialism?

JA: It’s tough to put a finger on. It’s a number of things. One: it’s the licence to be able to use found text and manipulate it into a form of critique or reorganize it so the underlining colonial logic in those texts is revealed, but it is also about the lack of boundaries that surround poetry. Poetry is a very open, artistic genre. There are very few constraints put on poetry. Poetry can be anything and I find that really interesting about the genre. It is so fluid and flexible that it allows for a whole range of creative intervention.

SB: Absolutely. Something I really appreciate in your work is the way you communicate the complexities of indigeneity using form and space on the page. Poetry as a genre can provide an alternative space to unpack the layers, the multiplicity of voices, and a variety of contexts surrounding indigeneity.

JA: One of the things that comes to mind when you are talking about layers and genres is that poetry is really good at being multi-genre. Thinking even of my latest book, it is built around 91 novels. It is build out of fiction, but it is also poetry. Even my first book, The Place of Scraps, that book is built out of non-fiction as well as erasure poetry as well as photography, as well as historic fiction. Poetry really seamlessly allows for multi-genre works and I think what I like about that is you can really bring the strength of other genres out in poetry as well.

SB: On that note, I read you worked with visuals in The Place of Scraps and that you had say on the interior design of the book, which is awesome. I was really intrigued if you had any say in the cover for Injun. It is an image by and of the artist, Rebecca Belmore. I was curious to know if you can talk a bit about your relationship to visual art and potentially intersections between her work and your own work.

JA: Talon has been an incredible publisher. In part because they allow me to have input in the book design and printing. We looked at a number of amazing indigenous artists. We ended up with the Rebecca Belmore photo. From Talon’s perspective, they were very interested in finding a piece of indigenous art that, in their words, looks back at the reader. I think this image speaks in particular ways to the content of the writing. It’s about addressing representations and images of indigenous peoples, but it is also about where indigenous senses of identity and belonging and community intersect with those representations of indigenous peoples. Belmore’s work on the whole is fantastic but this image really speaks in interesting ways to the writing itself.

SB: I would absolutely agree with that. Especially when you are thinking about representation and exploring and seeking to disrupt those representations through your work. The image seemed like a really good fit. I am going to ask a more conventional Rusty Toque question now. Do you have any first memories of writing creatively?

JA: I remember when I was in elementary school having creative writing assignments. I wasn’t particularly good at them. At the time I must have been about 10 and I was playing this video game with all this amazing dialogue in it and I was like, Oh, you know what I can do? I can take all this dialogue from this video game and then write in the rest of it and I did. It’s so funny looking back on that experience because at the time I didn’t think about it, but now I recognize that was actually a conceptual project.

SB: The next question I have is about the relationship between your books Uninhabited and Injun and how these collections really seem to be working in conversation. I loved the way you used separate collections to show the implicit link between derogatory representations rooted in colonization and how that feeds into the dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land. I am curious to hear about the relationship between the two books and how the various approaches and forms took shape separately?

JA: That’s a really good question. After I finished writing The Place of Scraps I was interested in continuing to work with found text and I ended up on project Gutenberg where I found that corpus of 91 western novels. My first move was to copy all those western novels into a Word document and then search that Word document and figure out what all these 91 books looked like together. One of the first words that jumped out at me was the word “injun.” When I copied and pasted the 500 and some sentences that contained the word “injun” the book work for Injun all came together in this really cohesive, quick way. After I was finished I felt as though I hadn’t even scratched the surface so I started pulling out all of these other search terms, many of which ended up in the book Uninhabited. The two books became separate projects because there was so much material in those 91 western novels. Injun to me is very much about exploring race and racism and the derogatory representations of indigenous peoples in westerns. I felt very strongly that Injun leaned towards but didn’t necessarily address fully the question of land and of course those issues are connected in really meaningful ways. The dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land is in many ways connected and mobilized by issues of race and racism. They are not separate things. The two books explore two sides of this corpus.

To borrow from Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman’s language, Uninhabited could be understood as a more pure conceptual book because it represents search queries about land, territory, ownership in their entirety. Although I’m not a huge fan of purity in conceptual writing, it can be useful to describe that kind of writing. There is this book called Notes on Conceptualisms written by Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman and one of the distinctions they identify is pure and impure forms of conceptual poetry. The pure conceptual poetry is transcribing something and that is the whole work and there is no intervention whereas impure conceptual poetry would be something more like M. NourbeSe Philips Zong! where it is very clear that there is a lot of artistic intervention and the concept is derived from one legal document, but there is not a specific process as to how she carves up that document. Thinking in that language, Uninhabited is much closer to being a pure conceptual project, whereas Injun is much closer to being an impure conceptual project. In part because Injun takes on a whole lot of lyric qualities because the long poem is very sonically and lyrically inclined even though it is also a cut-up work. To me, the difference between the books is not necessarily the content but the presentation.

SB: Yes, I can see that. The idea of the purely conception fits in relation to Uninhabited as you deal with ideas of search, terra nullius and these exploration narratives, whereas in Injun you are exploring more in-depth how the representation of indigenous peoples has been so manipulated, perpetuating stereotypes and misconceptions of the vanishing or imaginary Indian. It seems fitting that with your book Injun there is slightly more manipulation going on.

JA: I do think that is an important part of it. Tapping into that particular kind of manipulation was very important to those settler colonial writers who, through fiction, were shaping peoples’ understandings of who indigenous peoples were for their own benefit and really destructively doing so. Doing the same thing and manipulating their words in order to comment on that issue, to me, that makes the most sense as a kind of commentary.

SB: I definitely agree. Those narratives are still so pervasive. I know in my own experience that these colonial expectations of what an indigenous person looks or acts like can create a lot of misunderstanding and judgement. It’s complicated.

JA: Yeah, it is really complicated. I think lots of representations of indigenous peoples, not just in westerns, have really profoundly shaped settler understanding of who indigenous peoples are to this day. I think there is very often an expectation on behalf of settler people of who counts as an indigenous person, or who counts as being indigenous, or how someone should be indigenous, or what it should look like. And there is an expectation of performativity. I think that is also tied up in this issue of what it actually means to be indigenous for indigenous peoples and what counts as indigenous lived experience and how generally we experience indigeneity. There is this whole cluster of issues.

SB: I just wanted to take a moment to thank you are sharing your time and knowledge with me. I think it is important to appreciate the time, energy and labour that goes into talking about these things. So, I am curious to know, we were just talking about performativity and so I’ll switch gears a little and ask you about the performance of your poetry. I was watching an art lecture series you did for Evergreen. You spoke about being interested in the challenge of performing your poetry and you said you are most interested in those moments of the text that are difficult to perform. I was curious why performing those moments is important to you and what you hope people take away from your work.

JA: Those challenging moments are really interesting to me to perform in part because they are possible to perform, but when I talk to concrete poets, or poets in visual poetry, or artists interested in visual art, there seems to be an unwillingness in trying to engage the more difficult moments. I wonder about that because I am very interested in sounds and, to me, those moments present an amazing opportunity where I can think about these visual moments in terms of sound. I can re-think the spirit of what this piece is in another medium. I also have to admit that part of it is a result of being part of a creative writing classroom. There is always a moment in a workshop when they want you to read your poem and the things that I was producing were not actually readable. I realized I should be thinking about this and finding pathways to perform this and I enjoy that challenge. Not only do I enjoy the challenge of actually trying to do it, but I actually really enjoy manipulating all those sounds and finding pathways to these ideas through sound.

SB: I am so curious to know, were you already working on music and sound-based art or was this something you started investigating when you started thinking how can I perform this?

JA: Yeah, the second one. I am not a trained musician, I mean I am self-taught in really the worst way. I figured it out after a bunch of trial and error. The DJ I use I don’t even use for the purpose its designed for. The program I use is one called Ableton. It is so malleable and every key is programmable. Once I realized that, I realized I could drop any sounds I want into there. For DJs it could be a drum beat or something, but for me it is voice. The technology allows me to perform in a way that speaks to the core content of my work if not that actual work on the page all the time.

SB: That makes sense particularly because you work with layers and sound.. It’s awesome you were like I’m just going to try this. I’m just going to do it. That is really inspiring.

JA: It’s really honestly fun for me to do and I also have to admit the more that I do it, the more I am convinced that it is important to disrupt poetry spaces. There are a range of reactions I’ve gotten to my performances. On the one hand, there are people who really are into it and they like whatever it is I am doing and they think it’s cool and interesting and, on the other side, there are people who are like What the fuck is this? This isn’t poetry! They are really angered by it. I find that range of responses really interesting. I think with the performance specifically, the thing I am hoping to accomplish is to transport my work on the page to a work in the performance setting. Because of the kind of work that I do that is a difficult manoeuvre and also can be an uncomfortable one. Likewise the subject matter that I’m talking about is not easy subject matter; it is difficult subject matter. Sometimes the performance ends up being, from what I hear, somewhat uncomfortable for people or can be, and my response to that is, when people specifically tell me that it can be uncomfortable and my question is, is art supposed to be comfortable? I wonder about the purpose of art and what artists are trying to do, and what I’m trying to do. I think that for me, honestly, what I am trying to do is to talk about these really difficult issues in indigeneity that are not only tied to these deep textured layers of the western genre, but also issues of identity and representation that are actually difficult to parse out.

SB: Totally! Disruption is not comfortable. What I love about the performance space, at least from what I’ve seen of your work, is that it also creates space for exploring these ideas and offering space. I think about that a lot. How space exists in the CanLit environment and how we can work to create more space for ourselves, or for others. I’ve also been thinking a lot about the way repetition is functioning in the “Notes” section of Injun. I was wondering if you could speak a little about this section of the book?

JA: The way I think through it conceptually is that these sections are gesturing towards the larger corpus. They are aimed at branching out. There are all these moments that are connected to the long poem that when you find the accompanying word in the “Notes” section what you are getting is part of the concordance line for the rest of the corpus—so that is one thing. The second thing is that it really focuses on the practice of reading contextually. So when I pull out the 500-plus sentences that have the word “injun,” I am looking at the a very similar concordance line. I am looking at all these moments that the word Injun appears and all the moments that surround them. The notes section is essentially an attempt to address what reading contextually looks like. There is the concept in linguistic called the concordance line; it is aimed at reading contextually. You read contextually for a word and read five words before it and five words after it to give some idea of how that word is deployed. Reading this way is very disruptive and alarming because it focuses in on how common certain contexts are. For example, the redskins section. All of the context around that word seems negative. Reading in this way really brings out the connotations of each word and also complicates those connotations.

SB: What are you most excited or looking forward to right now, be it a book or a walk?

JA: I am really looking forward to Joshua Whitehead book full-metal indigiqueer. I am not very often a poetry editor, but I am helping out with the editing for this book and I am really looking forward to working on it more and seeing the finished product.

SB: And to finish. I’ve read a lot of interviews where you are asked what advice you have for emerging or new writers. It’s always a good, classic question. I am curious to know if there is anything you would have liked to tell your younger self?

JA: In the past, my answer has been Know people and do stuff, which I think is true. The writing and publishing world is kind of weird that way; it does help to have personal connections and it does help to be active and visible. Somebody said something very similar to me years ago and I felt it was good advice. If I were to give another piece of advice to someone like my younger self, I think it might be something along the lines of Keep believing in the work that you do, which kind of seems cliché but one of the things I ran into when I was doing creative writing workshops is that so many people were harsh critics and ended up not actually being that helpful in my process of writing. I very often found myself just having to put aside all the advice and just doing what I wanted. Looking back, I think that was a stronger move than I ever gave it credit. It is hard to not listen to people who are telling you what to do. Looking back I am glad I didn’t listen to everybody.

JORDAN ABEL

Injun

Talon Books, 2016

| Description from the publisher: Award-winning Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel’s third collection, Injun, is a long poem about racism and the representation of Indigenous peoples. Composed of text found in western novels published between 1840 and 1950 – the heyday of pulp publishing and a period of unfettered colonialism in North America – Injun then uses erasure, pastiche, and a focused poetics to create a visually striking response to the western genre. Though it has been phased out of use in our “post-racial” society, the word “injun” is peppered throughout pulp western novels. Injun retraces, defaces, and effaces the use of this word as a colonial and racial marker. While the subject matter of the source text is clearly problematic, the textual explorations in Injun help to destabilize the colonial image of the “Indian” in the source novels, the western genre as a whole, and the western canon. |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed