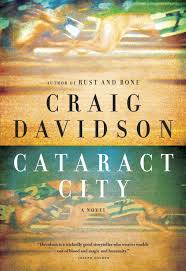

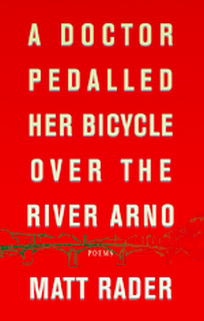

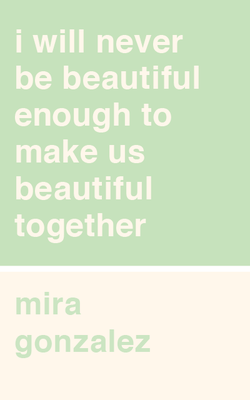

Craig Davidson Craig DavidsonPhoto by Kevin Kelly CRAIG DAVIDSON was born and grew up in St. Catharines, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. He has published three previous books of literary fiction: Rust and Bone, which was made into an Oscar-nominated feature film of the same name, The Fighter, and Sarah Court. Davidson is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, and his articles and journalism have been published in the National Post, Esquire, GQ, The Walrus, and The Washington Post, among other places. He lives in Toronto, Canada, with his partner and their child. RUSTY TALK WITH CRAIG DAVIDSON Madeline Bassnett: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Craig Davidson: Likely an assignment I did for grade 5 English; my teacher heaped it with praise, which was lovely I suppose, and encouraging, but later, when I was poor and couldn’t publish a thing, I sort of wished she’d said I sucked and ought to set my sights on a plumbing career instead. MB: You’ve received an MA in creative writing from the University of New Brunswick and an MFA from the acclaimed program at the University of Iowa. How did these different educational experiences contribute to shaping you as a writer? CD: I think they were ultimately more alike than I’d expected. Which means I likely did one degree too many. But what they did, more than anything, was give me the time to sit down, ass in chair, and get a lot of writing done. I failed a lot, got rejected a lot, failed some more, had some small successes, some more failures, then things got a little better. But of course most writer’s careers are loopy roller-coasters: there will be as many ups as downs. MB: You’re now a new dad. Has being a father changed your writing and/or your writing process? Has it changed what you’re interested in writing about? CD: I think primarily it’s solidified the idea that it is, for me, a job. I have to be up and working 5, 6, sometimes 7 days a week. It’s not glamorous. But I have to help provide for my family, as my father and mother provided for me. So it’s a big and sobering responsibility, and the only way I’ll manage to do it, as a writer, is if I’m busting my hump. Every writer I know handles themselves the same way, pretty much. There’s nothing really romantic to it, the way I’d envisioned it in grad school—although being working writer, and all that entails, is a very nice thing … for now. The wheels could spin off at any moment. But, having worked really hard, the only real way to stay in the same spot is to work just as hard. Thankfully I like working hard, and don’t have any of those preconceptions anymore about the glamour or romance of it; I understand that to be a writer, for most of us, means to write and write and write and get rejected and then maybe, if you get lucky, you catch a break. And I have responsibilities now that preclude me from being too precious about any of it—I work, I work, like my father (a banker) and my mother (a nurse) and my fiancée (a social worker) do. It’s a job. A great one, one I’m very lucky to have, but a job nonetheless. MB: Your first book, Rust and Bone (2006), a collection of short stories, was recently released as a critically acclaimed film (2012). What was it like having your stories transformed into a film? How did they turn these quite different pieces into one narrative? CD: It was fantastic. I was unbelievably fortunate. The stories were written when I was 25, 26, 27, 28—the stories off the pen of a sort of young man. They were adapted by a director in his fifties, who has a full command of his own craft. He added things to the stories that weren’t there, though he kept the rawness of them, which is likely their strongest quality. As to how they did it—movie magic! No, I think it was more a matter of finding two characters in separate stories and making their stories connect. MB: You also write horror fiction under a pen name, Patrick Lestewka. And I believe you’re more recently moonlighting as Nick Cutter. Why do you use a pen name for your genre fiction? Why two names? CD: That’s kind of my agent’s idea. He’s a good agent, I trust him, so I trust his guidance on this. Sometimes writers want a kind of separation between church and state—or in my case, a separation between gooey slime monsters and whatever literary endeavours I may decide to try down the road. I’m not really for that separation, but it is what it is. For my part, I make no real attempt to keep up the charade; it’s pretty easy to figure out that I’m all those guys! MB: Your recent book, Cataract City, is a novel about male friendship, revenge, and the power of place to shape and control our lives. It was short-listed for the 2013 Giller Prize. How did it feel to be on the short-list, and do you see this honour having any longer-term impact on your writing? CD: It was a lovely and unexpected experience. It was also tremendously lucky, as I would imagine most shortlisters would say; there’s always books that could take the place of your book, so you just have to count those lucky stars. I don’t think it’ll have an impact in terms of what I write about, no; I’ve always kind of written what I write and never expect to get any awards attention at all. I’m not really expecting to get nominated again, to be frank. It was a Halley’s Comet nomination, never again to be seen in my lifetime, and honestly I’m OK with that. MB: When I was reading Cataract City, I often thought about your gig writing horror, especially when the two boys, Owen and Duncan, wind up in the woods with their wrestling hero, Bruiser Mahoney. After Mahoney dies, the twelve-year-old boys have to survive an arduous and frightening journey back to civilization. You succeed very well in communicating the visceral horror of the situation. Do you feel that your writing of horror influences your other writing, and vice versa? CD: Absolutely. My horror book, The Troop, is about a bunch of Boy Scouts stranded on a tiny island off PEI; I wrote it in 5 weeks after finishing Cataract City, because I really enjoyed writing those boyhood sections in the novel and thought it would be good to focus on characters at that age again, except in a more overtly horrific scenario. So one side of things does impact the other, for sure. MB: As in Rust and Bone and The Fighter, Cataract City’s men are fighters, and not only in the metaphorical sense. Duncan gets involved in brutal bare-knuckle fights, and is dragged into dog-fighting matches. What draws you back to these scenes of male violence and competition? CD: Oh, good question. I think, to be honest, I’ve glutted myself on that world. The overtly male. But at the time of writing, I guess I felt that … well, listen, we all feel there are areas of human experience that we can map best. So those were mine. But I feel like I’ve mapped that area pretty damn thoroughly now. Maybe in a few years, a decade or two, I may come to some personal reckoning or something to do with my son that asks me to enter that realm again and write on it, but for now I think it’s time to hang up my boxing gloves, wrestling trunks, and so on. MB: Cataract City is also about a place: Niagara Falls. It’s a fascinating depiction of what lies behind the tourist trap around the Falls. You grew up partly in St. Catharines, just down the road. How does Niagara--and place more generally--influence you and your writing? CD: Hugely. I never really understood until it dawned that all my books were set in the area. I never considered myself a “place-based” writer, the way David Adams Richards is, for example, so many of his books set in the Miramichi. But clearly, I have that same sense of things. The results bear that out. Every book is set, at least partly, in that area. I used to think it was just because I knew those streets best—and partly, that’s exactly why I set stuff there. But I know those streets and feel comfortable about writing about them, too. And since writing a novel is often a daunting task, you need a few implicit sureties before setting out. Either the plot, or a strong character, or the place where you’re setting it. So I know that place well, and that gives me confidence—and with writing, as with many things, confidence is key. MB: What are you working on now? CD: Just being a bum, really. I’m looking after my son while my fiancée gets her Masters of Social Work. So the imagination is laying fallow right now!  CRAIG DAVIDSON’S LATEST BOOK Cataract City, published by Doubleday Canada, Random House, 2013 Read an excerpt of Cataract City in MACLEAN'S. Description from the publisher: Owen and Duncan are childhood friends who've grown up in picturesque Niagara Falls--known to them by the grittier name Cataract City. As the two know well, there's more to the bordertown than meets the eye: behind the gaudy storefronts and sidewalk vendors, past the hawkers of tourist T-shirts and cheap souvenirs live the real people who scrape together a living by toiling at the Bisk, the local cookie factory. And then there are the truly desperate, those who find themselves drawn to the borderline and a world of dog-racing, bare-knuckle fighting, and night-time smuggling. Owen and Duncan think they are different: both dream of escape, a longing made more urgent by a near-death incident in childhood that sealed their bond. But in adulthood their paths diverge, and as Duncan, the less privileged, falls deep into the town's underworld, he and Owen become reluctant adversaries at opposite ends of the law. At stake is not only survival and escape, but a lifelong friendship that can only be broken at an unthinkable price. RUSTY TALK WITH MATT RADER Matt Rader Matt RaderPhoto by Ron Pogue Matt Rader is the author of three collections of poetry, Miraculous Hours, Living Things, and most recently, A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno. His poems have recently appeared in publications in the United States, Romania, the Czech Republic and Canada. He lives on Vancouver Island. Kerrie McNair: How did you first get into writing? Matt Rader: That’s one of those questions of history I’m always tempted to rewrite. I probably have several times. I recall writing in school as a kid. And I recall writing poems with my mum when I was eight or nine. Then I wrote poems all through high school. I took writing classes at the University of Victoria from age 18-21. But I didn’t start seriously until the fall after I graduated from my undergrad. That fall I wrote a poem called “Exodus.” Later that poem became the first poem I published professionally in sub-Terrain magazine. KM: What poets or writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now? MR: In those earlier years after my time at UVic, I read Ted Hughes exhaustively. Then I read Seamus Heaney who remains a major influence. Michael Longley was my primary influence for more than half a decade. In the last few years Larry Levis has been hugely important, and most recently I have fallen in love with Mary Ruefle’s poems. Heaney, Longley, Levis, and Ruefle are all currently represented in the Jenga of books on my bedside table. I could also tell this story with Homer, Keats, Hardy, Yeats and Eliot. Or Bishop, Plath, Lowell, Gilbert, and Larkin. Not to mention Babstock, Solie, O’Meara, Thornton, and Bachinsky. The problem with any list like this is that I can’t help but make egregious and unforgivable omissions. KM: You used to run a literary micro-press out of Vancouver for writers who were marginalized for a variety of reasons including age, content matter, sexuality and ethnicity. Can you describe how you got into literary/cultural activism and how it informs your writing? Are you working on any community projects at the moment? MR: I was lucky enough to meet a set of young artists and writers, largely centred in Vancouver in the early aughts, who had a desire to share their work with each other. Many of us had grown up in the DIY music and zine culture. Several of us were involved in various queer communities. We were culture makers and pursued that right into our publishing deals and writers festival invitations. I’ve been involved in several projects lately and there are few more in the works. A year ago I collaborated with my friend Grant Shilling to put on a community storytelling event. We live in a small mountain village on Vancouver Island. The foothills here have been ravaged over the last century and a quarter, first by coal mining and then later by logging. Currently the hills around our village are used both industrially for logging and recreationally as a major mountain biking destination. The event was called Bronco’s Perseverance: Changing Gears in Cumberland. Bronco’s Perseverance is the name of one of the main trails along Perseverance Creek. The trail is named after the long time Cumberland mayor, Bronco Moncrief. Our tagline was “Beer and bullshit.” It was amazing. This past summer I collaborated with a local designer, Sarah Kerr, to create large poster-sized newspapers modeled on papers from the 1913 that we researched in the Cumberland Archives. There were six pages and they told the story of two young girls during the height of the Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike that was 100 years ago this summer. We put the posters up around town. I wouldn’t say that my cultural activism informs my writing exactly, but I do think my writing is informed by the same impulses as my cultural activism. I can be didactic about it and try to make a case for aesthetic and moral value, for form and identity, for art as experience, but in the end, those impulses are as known and as mysterious to me as to anyone else. KM: You’ve been involved in curating several reading series such as the Robson Reading Series. Do you have any advice for new poets or writers on reading their work for an audience? MR: Read as slowly as you possibly can, then read a little bit slower. Always read less. I believe Mark Twain has a set of rules. Google Mark Twain’s rules. KM: Can you describe the writing process for your most recent collections of poems, A Doctor Pedaled Her Bicycle over the River Arno, which your publisher describes as unraveling “our layered identities to explore the lyrical fabric of humanity”? Over what length of time were the poems written? Was there a particular catalyst for this project? MR: The earliest poems in A Doctor were composed alongside the bulk of my previous collection Living Things and I was in the midst of composing the core poems in A Doctor when Living Things came out. All told, it probably took about three years to write. I was pursuing several things in that book. One was a reintegration of narrative into the poems, something that I felt I’d written out of my poetry in Living Things. Secondly, I was exploring cultural history in a way that I had explored ecocultures in Living Things. I was particularly looking at my family history on one hand, and the colonial and post-colonial history of coastal British Columbia on the other hand. It wasn’t really an either/or. These histories were more braided than that description suggests. Thirdly, I had been thinking since Living Things about poetic form and tradition and in A Doctor that became expressed as custom and customs. I was intrigued by the idea that custom and customs (or costumes as Elizabeth Bishop would have it!) can be both the guarantor of civilization and a purveyor of horrific violence. KM: Many of the poems such as “I Acknowledge: and “History” in A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle over the River Arno detail the lasting presence of history in contemporary life. How did the past motivate your desire to define the present when it came to writing these poems? MR: John Dewey says “art celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reënforces the present and in which the future is a quickening of what now is.” I really like how he says, “what now is” instead of “what is now.” I know that I should be more generous and explain what I think this means, but I don’t want to. I tend to see everything relationally, which is to say with a kind of historicity. KM: Conversely, poems like “Natural Lives” and “Homeowners Manual” address sentiments of devotion. Was it a conscious decision to, at some point, stop looking back? MR: No. I never did stop looking back. Though I don’t think of the past as being “back there.” Looking at history is looking in the mirror. Looking in the mirror is looking at history. KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one? MR: When I was a small boy Dennis Lee came to my small island town and gave a reading for children. I remember the bookstore as having creaky old wooden planks for a floor. Everything seemed very dark. He picked me out of the crowd and sat me on his knee and began to recite a poem. To which I promptly ran away crying. Then, nearly thirty years later, after the launch of my last book in Toronto, I walked out the party and standing in the street at the bottom of the stairs was Dennis Lee. He was holding my book! I introduced myself and we said kind things to each other and then I told him the story I’ve just related here and he said … well, I can’t tell you what he said, not in print. But if I’m ever in your town you can buy me a beer and I’ll tell you the rest … KM: What are you working on now? MR: I have a collection of short stories that’s meant to come out next fall. I’m also working on a new book of poems with a kind of deep hermetic code. They’re largely elegiac. I’m also about to embark on a filmmaking project with a young filmmaker, called Jim Vanderhorst. I have a chapbook of poems coming out with Baseline Press at some point in 2014. Enjoy an excerpt from Matt Rader's forthcoming chapbook from Baseline Press: UNSPEAKABLE ACTS IN CARS It’s the first day of summer and we’re so happy To see the sun and the satchel of colours it schleps All those dark kilometres. The sky is so blue And the sea is blue and the small islands in the sea Are blue also. How our sun must love blue. We have beachgrass and bull kelp and lion’s mane And we love them all because we love the sea Which is cold and buoyant. Friends now of seasalt And knotweed, the mountains know all about us And who we are when we are most ourselves. But their blue haughty distances are no help. We are who we are with mock orange and wisteria. We’ve nothing to bitch about. The high cirrus Can’t touch us. We been alive just long enough. originally published in The Fiddlehead 253 DOVE CREEK HALL (FORMERLY SWEDES' HALL) The children play their fiddles so slowly I am sad For the old wooden hall among the cow patties. Who cut the rhodo blooms and set them on the piano? They bow tiredly through every tune. Even the cows Have wandered away from the music to the far side Of the pasture. All the Swedes who built this hall Are dead now and the women they married are dead And the pastor who married them and their friends. But the children do not know this or just how sad Beauty is on the last day of spring with instruments And young players making music beneath the rafters. They play along with mistakes and embarrassment. Tell me, who hung the hand-stitched stars on the wall? Who hung the evening light from the windows? originally published in Arc 67  MATT RADER'S MOST RECENT BOOK OF POETRY A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno House of Anansi Press, 2011 Description from publisher: A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno carries within it all the technique, vision, imaginative labour, and razor-sharp precision of Matt Rader’s first two collections, Living Things and Miraculous Hours. But it also ascends to a new and luminous, demanding, particularized realm of the human. Wildflowers and weeds, newspaper archives and illness, hostels and hostiles, parenting and the shadowy history of grandparents, war and Renaissance paintings: Matt Rader’s unassuming, deeply spirited, and expansive poems show us again how contemporary lyric can go such a long way toward revealing our true homes to us at the moment we find ourselves most nakedly un-housed. Rader seeks out limits, borders, and frontiers—those mapped for us by authority, and the concomitant, interior shadowlines we ourselves draw—in order to test their validity.  Mira Gonzalez Mira Gonzalez Mira Gonzalez [b. 1992] is from Los Angeles, California. She is the author of i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together (Sorry House, 2013) and is widely published in print and online. She currently lives in Brooklyn, New York. RUSTY TALK WITH MIRA GONZALEZ Sara Jane Strickland: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Mira Gonzalez: when i was i think, 10 (?) i wrote a ~15 page story about aliens invading the world and like one girl stops them or something. i remember the girl had a boyfriend in the story, i remember at one point she cooks hot dogs. thats all i remember about it SJS: What influences your writing the most? MG: i think anything i enjoy reading will influence my writing, to some degree. some things more than others. 'big' life events, like relationships etc. also make me feel more inclined to write SJS: What is your writing process like? (Do you write every day? Where? When? Etc.) MG: i used to try to write every day but i work like 47 hours per week now so its difficult for me to find time. i would like to work less and write more. i would say my 'process' is like 10% writing and 90% editing. every time i write a poem i probably write 2-3 pages worth of stuff then spend a lot of time editing it down into something that, i feel, expresses what i want to express, and is something i would want to read SJS: Your book, i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together, sifts through many ideas that have to do with the sensation of touching, which seem to serve more as a source of isolation than for connection. A lot of the poems seem to overlap and connect. How did you approach the structure of the book? Did you intend for it to have a narrative? MG: all the poems in the book are about events in my life, so i guess in that sense it has some sort of narrative maybe, if you would agree that 'life' in general has a narrative, which i dont think it does. all the poems were written during very different points in my life and sometimes there is a huge span of time between the poems where i wasn't writing at all, or didnt include poems from a big chunk of my life. spencer and willis and i spent a long time choosing the arrangement of poems in the book, but it wasnt so that we could create a narrative exactly ... it was more for aesthetic purposes or something SJS: The book deals with a variety of gut-wrenching subjects, such as loneliness, drug-use and unfulfilling relationships. At the same time the tone is objective and unattached. What made you decide to write about these subjects in this way? MG: i think i just wrote about how i felt when [whatever thing] was happening to me. there will always be some distance between the event and the reader i suppose, because its happening to me and not them, so i try to write about things in a way that is more easily understood by more people, which might make it sound 'objective' or 'unattached', i think. that seems good/fine to me SJS: How do you approach revision? MG: if i reread something i wrote and i don't feel satisfied with it i revise it. i revise things constantly SJS: You are very active on Twitter and your tweets are often funny and quirky, but also insightful and compelling. How would you say that social media websites such as Twitter have influenced contemporary poetry? MG: i think i have no idea how to answer this question. i dont know. i view twitter as another platform to express things through writing. the same way you would express something different with a story than with a poem etc. i cant speak for anyone but myself though SJS: How long did it take you to write i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together? MG: i think the oldest poem i wrote in the book was like, 3-4 years ago, but most of the poems werent written with the intention of creating a manuscript. i cant remember how long it took from the beginning of compiling the manuscript to publishing it. maybe a little less than a year SJS: Are you working on anything right now? MG: yes. i plan to write another book but its still really really in its beginning phases so please nobody hold me accountable  MIRA GONZALEZ'S MOST RECENT BOOK i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together, Sorry House, 2013 Description from publisher: Mira Gonzalez is a phenomenon of the same breed as Tao Lin: she might actually be the only literary social media presence more prolific and more intense–flitting between her two Twitter accounts, @miragonz and @miraunedited, is a kind of poetry in and of its self and fairly representative of her first collection. Either brutally honest to the point of appearing unhinged or wildly fantastic, but totally engrossing regardless. Read an excerpt from her book here.  Alexis O'Hara Photo by Annie-Eve Dumontier Alexis O'Hara Photo by Annie-Eve Dumontier Alexis O’Hara tends to an interdisciplinary practice that exploits allegories of the human voice via vocal & electronic improvisation, sound installation and text-based performance. She has released one book of poetry, two music CDs and a number of experimental mini-CDs. With Subject to Change and The Sorrow Sponge - two projects involving wearable electronics, direct audience interaction live performance using field recordings - she flirted with interactive documentary performance. Her sound installation, SQUEEEEQUE, an igloo built of recycled speakerboxes, has toured many exhibits and festivals including Club Transmediale in Berlin and Elektra in Montreal. She has shared the stage with amazing artists including Diamanda Galàs, Ursula Rucker, Henri Chopin and TV on the Radio. Her eclectic performances have been presented in diverse contexts in Slovenia, Austria, Mexico, Germany, Spain, The United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Belgium and across Canada and the US. Alexis and her drag king alter-ego, Guizo LaNuit are mainstays of the Montreal cabaret scene. RUSTY TALK WITH ALEXIS O'HARA Sara Jane Strickland: What is your first memory of being creative (writing, art making, etc.)? Alexis O'Hara: When I was four years old, my family lived in a small town outside of Geneva in a one room apartment. My parents' bed was surrounded by a curtain that my little sister and I would use as a stage. We tucked the corners of kleenexes into our tights to make "tutus" and danced on our tippy toes for Mom & Dad. Later, every Easter/Christmas/Thanksgiving, I would boss around cousins and force them to do nativity plays/fashion shows/skits for our parents. SJS: When did you realize that you wanted to be an artist? AO: After I realized that Charlie's Angel was not a real job, I wanted to be an actress. Around age 20, I got really disheartened by the business of show business, possibly having a crisis of confidence that I was not thin/pretty enough to be an actress. I've written poetry since I was a kid, and made things too, but I always considered my collages, jewelry, sculptures...to be "arts & crafts". I can't say I felt comfortable calling myself an artist until I was about 30. But I've never actually "wanted" to be anything else than someone who is involved in artistic projects. SJS: How would you describe your own personal process of making art? AO: I'm terribly undisciplined so I tend to seek out external deadlines to motivate myself. Sometimes an idea just shows up and nags and yanks at my subconscious until I make it real. But usually I create in preparation for public presentation. This past summer, I made a lot of work just for the sake of making it. I was so unaccustomed to this idea of failure, making something that is just an experiment. But of course, I've had a lot of failures and experiments when it comes to live performance. A good ten years worth of my public performances were entirely improvised and therefore very subject to the whims of circumstance – some soaring successes and some horrible failures. I have to thank all the known and unknown audience members who witnessed this very public "personal process of making art". SJS: What influences your art the most? AO: Stuff that makes me angry, stuff that makes me swoon, heartbreak, my niece, Olivia, the desire to make a mark, the desire to make people laugh and talk to each other. SJS: What artists/writers/poets would you recommended to someone aspiring to be an artist or writer? AO: Sometimes I wish I could go back in time and be a better pupil. For years I closed my eyes and ears, thinking that everything I created had to come from deep inside an innocent, almost ignorant place. And then you make something that you think came just from you and someone says: "Oh that's just like *name of someone you've never heard of*". Ah, and who am I to say what ended up being good for me would be good for anyone else? I can list my favorite artists and writers, but will they be helpful to aspiring artists? Who knows? What I recommend to aspiring artists and writers is just that they do it! Work on it! Ignore what is trendy or cool. Believe in your own voice, even if you don't see it reflected out there. I know I will forget some but off the top of my head, here are some artists who have resonated with me: Lynda Barry, Pipilotti Rist, Ai Wei Wei, Gerhardt Richter, Katherine Dunn, Laurie Anderson, e.e. cummings, Takashi Murakami, the Mad Magazine artists, Dr. Seuss, Janet Cardiff & George Bures, Beat Takeshi Kitano, Lydia Lunch, Rebecca Horn, Buckminster Fuller, Marcus Aurelius, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Andy Warhol, Brian Eno, David Bowie, Miranda July (the recordings), Theo Jansen, Frida Kahlo, Ivor Cutler. SJS: What is it about audio installations/performance art that appeals to you as a medium for expression? AO: It's cheaper than making movies but can provide the same sort of multi-sensorial, immersive experience. SJS: Your piece Squeeeeque – The Improbable Igloo is a particularly interesting audio installation/sculpture. What inspired you to build an igloo made of speakers? AO: It came from a dream I had. My head was a microphone and I lived in a house made of speakers. Every time I went by the walls, a wailing screech erupted. When I woke up, I thought about this idea of a house made of speakers. Since the speakers are blocks, it seemed like an igloo was a perfect structure. At first I thought the project was about feedback and recycling rejected technology, but then it turned out that it was really about collective vocal improvisation. SJS: What are you working on now? AO: As usual, I'm juggling a bunch of projects at once. I just got back from Serbia where I built a speakerbox igloo and premiered a performance where I use helium balloons to get my dress caught in a chandelier. I'm working with my friends 2boys.tv on their new performance work, Tesseract. I'm getting ready for a residency at Recto-Verso in Quebec City where I'll continue work on an installation called La Couvée, that simulates the experience of being in a giant egg sac. I have two new musical projects. One is very tender, with a lot of sad songs. The other one involves my alter-ego Guizo LaNuit and Stephen Lawson's alter-ego, Gigi Lamour. I believe I can claim that it's the world's only drag king / drag queen party medley duo. We're called GuiGi and we're going to be huge. We're playing a retirement party in December and I'm hoping we can book a bunch of gay weddings in 2014.  Photo by Nikol Mikus Photo by Nikol Mikus Alexis O'Hara's sound installation, SQUEEEEQUE, an igloo built of recycled speakerboxes, has toured many exhibits and festivals including Club Transmediale in Berlin and Elektra in Montreal. |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed