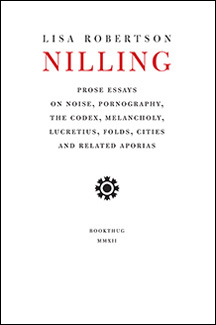

Lisa Robertson For many years LISA ROBERTSON has worked across disciplines and often in collaboration. With the late Stacy Doris she was the Perfume Recordist, an ongoing sound performance and writing project with work in the new I'll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women. She worked as The Office for Soft Architecture, publishing reports, essays, walks and manifestoes as well as curating and cooking as OSA. Currently she is translating the French linguists Emile Benveniste and Henri Meschonnic with Avra Spector. Her most recent book of poetry is R's Boat, from University of California Press, and Bookthug published a new book of essays, Nilling, in spring 2012. She lives in rural France, and teaches at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. RUSTY TALK WITH LISA ROBERTSON Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative? Lisa Robertson: I think my earliest creative acts were acts of deception and truth bending—petty theft, rebuttal, cover-up. This led directly to writing. KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.) LR: Everyday I sit in an armchair and write in a notebook as I read. If somebody gives me resources I leave the armchair and travel to read in an exotic library. Writing on trains and airplanes on the way to and from these libraries is a special pleasure, because so much anticipation and repletion is involved. Talking to my friends usually shows me how to work with the material I have gathered. My dearest friends are the ones I simply obey. KM: How would you define experimental writing? LR: I wouldn't define experimental writing. It would cease to be experimental then. KM: What influences your work? LR: Unanswerable questions. Unanswerable to me that is. Right now I am trying to understand the movement a triangle sections, and I am trying to understand the humoural system of medicine. Put more simply, desire influences my work. KM: What have you read recently that excites you? LR: I just spent a month reading at the Warburg Institute in London, for 6-8 hours a day, six days a week. Everything excited me. I was reading about the relationships between geometry, astronomy, optics, and medicine in the ancient world, until the baroque era and Johannes Kepler's work on the elliptical orbits. I wanted to understand the dynamics of the ellipse, and I wanted to understand science as a relational query into the structure of the cosmos, rather than a recitation of the mechanics of cause and effect. Plato's Timeaus is hallucinogenic in that respect. So is Kepler's The Six-Sided Snowflake. So is medieval Arabic optics. These studies are enticing me to draw more, and that is a pleasure. In terms of recent poetry—Erin Moure's translations of Galician poet Chus Pato, Aisha Sasha John's new work, Angela Carr, the American poet Chris Nealon, and Francis Ponge. I read Ponge as a contemporary. KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you've heard or been given that you actually use? LR: Writing is the good use of boredom. I try to have a boring life. I don't socialize, and I eat nine servings of vegetables a day. KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one. LR: When Jam Ismael read at KSW in 2002 she sat a tape recorder on a windowsill and played a cassette recording of New Delhi crows. Vancouver crows came to the open window to listen and respond. Every emotion cracked open at once. KM: What are you working on now? LR: I am simply reading and learning, and making the occasional paragraph or drawing as record and exploration.  LISA ROBERTSON'S MOST RECENT BOOK Nilling, Bookthug, 2012 Description from the publisher: Nilling: Prose is a sequence of 6 loosely linked prose essays about noise, pornography, the codex, melancholy, Lucretius, folds, cities and related aporias: in short, these are essays on reading. Excerpts from Nilling: EXCERPT 1 I have tried to make a sketch or a model in several dimensions of the potency of Arendt's idea of invisibility, the necessary inconspicuousness of thinking and reading, and the ambivalently joyous and knotted agency to be found there. Just beneath the surface of the phonemes, a gendered name rhythmically explodes into a founding variousness. And then the strictures of the text assert again themselves. I want to claim for this inconspicuousness a transformational agency that runs counter to the teleology of readerly intention. Syllables might call to gods who do and don't exist. That is, they appear in the text's absences and densities as a motile graphic and phonemic force that abnegates its own necessity. Overwhelmingly in my submission to reading's supple snare, I feel love. EXCERPT 2 In the facsimile Oblongus Codex, at the bottom margin on the page containing lines 1140-1159 of the fourth book of De rerum natura, I saw what at first appeared to be the photographed image of a small oval hole about the size and shape of my thumbnail, tidily cut from the vellum of the original. Bordering this ellipse, I saw a faint drawing that added a labial ornamental border around the shape. It seemed that some sort of monkish pornographic doodle had been censored. At closer examination I realized that the elliptical absence had in fact not been cut from the page by some historical censor--it was rather a flaw inherent in the structure of the vellum; the trace of a wound perhaps. Several of these photographed images of material mise-en-abimes appeared as I leafed through the codex. In each case the page was cut from the larger skin so that the scar found its place in a margin, so as not to interfere with the scribe’s work. But here in book four, the scribe had decorated the flaw in the skin with this mildly and endearingly erotic doodle. The tiny absence was animated: a lacework.  Erín Moure Photo by Karis Shearer Montreal poet Erín Moure has published seventeen books of poetry plus a volume of essays, My Beloved Wager. She is also a translator from French, Spanish, Galician (galego), and Portuguese, with eleven books translated, of work by poets as diverse as Nicole Brossard, Andrés Ajens, Louise Dupré, and Fernando Pessoa. Her work has received the Governor General's Award, the Pat Lowther Memorial Award, the A.M. Klein Prize (twice), and was a three-time finalist for the Griffin Poetry Prize. Moure holds an honorary doctorate from Brandon University. Her latest works are The Unmemntioable (House of Anansi), an investigation into subjectivity and wartime experience in western Ukraine and the South Peace region of Alberta, and Secession (Zat-So), her fourth translation of internationally acclaimed Galician poet Chus Pato. RUSTY TALK WITH ERÍN MOURE Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative ? Erín Moure: Biting my toe in the crib and finding out that the waving thing was intimately connected to me. Ouch! KM: Why did you become a poet? EM: From the time I read Mother Goose when I was 3 or 4, I thought poet was a valid career choice and no one ever really managed to talk me out of it. It interested me more than my next hotly desired direction, which came later: restaurant owner. KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.) EM: Hard to describe. I write most days. I write in pencil in notebooks, I move words, I collect words and bits of text from the Web and elsewhere, I translate and use automatic translators, I generate funny sentences, try to write things down before I forget them. I research a lot too: read philosophy, history, buy plane tickets and go to places: Lisbon, rural Galicia, L'viv in Ukraine. Immerse. Usually by myself so I feel utterly lost. Get really lonely. Revise a lot. Move, cadence, check, read aloud, set aside, read again, move. Read a lot of good poetry while I am working and then cut where mine falls short...no mercy, but lots of fun. I write wherever I am but favourite places are while on my bike (I have to stop to scribble), while on trains, while on the roof deck, while at my desk...but anywhere will do really. I change places so that the work can be read differently. Inhabit language and let it inhabit me. I think. Thinking is a kind of writing too. KM: How did you get interested in translation? How do you view the role of the translator? EM: I've told this story before...it's because my mother—Ukrainian born but fiercely always an unhyphenated Canadian, her way of coping with history—always told me there were two languages in Canada, French and English. As a tyke in Calgary, I knew we spoke "English" so I thought French was spoken on the north side of the Bow River. I thought my grandparents spoke French. Then I found out they spoke something that was not French. And I knew there were three languages in Canada. Then I read Tarzan of the Apes by Edgar Rice Burroughs. At the back there is a three page bilingual dictionary of Ape-English. So I tried to write in Ape. No English-Ape dictionary though, and no connecting words, so it was impossible. I was maybe 7. The role of the translator? To transfer joy from one idiom to another. Somehow. KM: What poets would you recommended to an aspiring writer? Or what poets or writers were influential to you when you first started out? EM: Read poets in other languages as well as in English: try to read them even if you can't, look intensely at their language. Poets that helped me: Yannis Ritsos, Cesar Vallejo, Federico García Lorca, Clarice Lispector, Nicole Brossard. Early important poets to me: Phyllis Webb, Miriam Waddington, Robin Blaser, Al Purdy, Baudelaire. And Chus Pato, more recently, because, to tell the truth, I am always first starting out. KM: How do you think the early poet in you would view the later poet? Have you become the writer that you thought you'd be when you first started out in terms of the kind of work you produce, your views, etc. EM: I am still the early poet! I still love the surprise of exploring in language. I don't know what I've become, to tell the truth. I leave that to other people to define. I am still trying to bite my toe. Though, I guess, early on, I could have never predicted Elisa Sampedrín. Or that I would one day speak Galician. KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one. EM: Don't really have one...most things are funny, if you ask me...My favourite would be reading, just reading, always reading, and the feeling of incredible beauty and joy I get in my mouth and throat and chest when I am reading. And going to Vylkove to the Danube Delta with Chus Pato and Manolo Igrexas and swimming in water salt and fresh at the same time. KM: What are you working on now? EM: Am working with monologue and chorus texts that could potentially I hope be staged. Poetry but theatre too...delving deeper into that. It's in English and French at once. And is called Kapusta, which is Ukrainian for cabbage.  ERÍN MOURE'S MOST RECENT BOOK The Unmemntioable, House of Anansi Press, 2012 Description from House of Anansi The Unmemntioable joins letters that should not be joined. There is, in this word, an act of force. Of devastation. The unmentionable is love, of course. But in Moure's poems, love is bound to a duty: to comprehend what it was that the immigrants would not speak of. Now they are dead; their children and grandchildren know but an anecdotal pastiche of Ukrainian history. On Saskatoon Mountain in Alberta where they settled, only the chatter of the leaves remains of their presence. What was not spoken is sealed over, unmemntioable. There is no one left to contact in the Old Country. Can the unmemntioable retain its silence, yet be eased into words? Can experience still be spoken? |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed