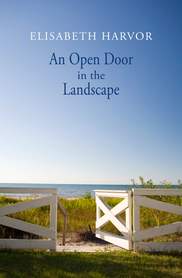

Elisabeth Harvor Photo by Andrew Chowmentowski. _Elisabeth Harvor's fiction and poetry have appeared in The Malahat Review, The New Quarterly, The New Yorker, PRISM international, Best Canadian Stories, and The Best American Short Stories anthologies, and in many other anthologies and periodicals. Her first novel, Excessive Joy Injures the Heart, was named one of the ten best books of the year by the Toronto Star in 2000, and her most recent story collection, Let Me Be the One, was a finalist for the Governor General's Award. Her first book of poetry, Fortress of Chairs, won the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for 1992. An Open Door in the Landscape, her third book of poetry, was released in September 2010. RUSTY TALK WITH ELISABETH HARVOR Kelli Deeth: How do stories and poems come to you? Elisabeth Harvor: The music of certain lines comes to me—and keeps coming to me—like a line of a song or poem remembered, but it's a beat that isn't consciously from any song or poem I’ve ever read or heard. So this is how a story or poem begins. With poetry, the opening line can sometimes sound like a maxim with self-deprecation in it. Take the beginning of the poem called "I Am A Scientist" which begins with the words Like all paranoids, I am a scientist Dark Cause + x = Predestined Effect, that is, if someone doesn't like someone, namely x and if x = me, then I'm turned into a sleuth in the name of survival... I can't see these lines as the opening of a story, they are too rhythmic, too insistently declarative. Another example of opening lines that feel as if they need to become the beginning of a poem—and only a poem—are the opening lines of "Island of Illness": All winter long this has been lying in wait for you, island of illness, lap of warm waves at your pillow... This doesn't at all sound like the opening of a story to me either, and although I can't swear that I changed the first-person voice into the second-person voice because I didn't want the poem to have too much self-pity in it, it does seem to work best in the second-person voice. And why is this? Because the second-person voice feels, paradoxically, both more intimate and more universal. The openings of stories or novels, on the other hand, are usually more languid. I can feel the story-telling impulse when I "get" the first lines. Take the opening of a story called “Love Begins with Pity” in Let Me Be the One, a story in which a poet in her thirties falls more than a little in love with a young man who's a student in a series of high school workshops she is leading: "Why are you laughing?" she asked them. She even smiled at them a little although falsely, surely, for she was feeling damp from apprehension. KD: How would you describe your approach to revision? EH: I value it. It's a purge and a freedom and a benevolent addiction. It’s also a second chance. Or a whole series of second chances, and as time goes by, I'm more and more grateful for second chances. But my approach to these second chances? It's often a matter of delete, delete, delete, especially when revising poetry. But it's a question too: Have I made the best emotional use of the space on this page? And also: Have I gone deep enough here? KD: Your work is very honest. Do you think emotional honesty in a story, poem, or novel is absolutely essential? EH: I do, but this conviction doesn't appear to rule out the occasional enjoyment of fictional inventions, fabrications, and lies. As both a writer and a reader, though, I prefer those moments when the surreal enters the real and does it naturally, without show-offy artifice. KD: What other writers inspire you? How do they inspire you? EH: Woolf’s To the Lighthouse for its mesmerizing voice, for its profound understanding of childhood, and for the depth and complexity of its emotion; The Journals of Sylvia Plath for its joie de vivre and its brilliant fury; William Carlos Williams for "The Ivy Crown;" one of the great love poems of all time; Penelope Mortimer for her authentic evocation of depression and the fierce economy of The Pumpkin Eater; Saul Bellow for the deep anguish and comedy of Seize the Day; Bernard Malamud for the inspired comic originality of A New Life; Paulette Jiles for the stomach-dropping drama of "Night Flight to Attawapiskat;" Grace Paley for "A Conversation with my Father," a terrific story about writing a story; Marian Engel’s tender ode to a bear in Bear; Nadine McInnis’s fetching (if frustrated) mother in "Legacy," and almost every poem in Plath’s extraordinary Ariel. As well as the work of so many other writers. KD: What would you say are the rewards and challenges of a writing life? EH: The challenges are a big part of the pleasure of throwing yourself into the work. When I was younger, though, I resented any suggestion that anything I wrote might benefit from revision. I couldn't bear to tamper with what I saw as perfection! Back then, so-called real life also took so much of my attention away from my writing life, but once my children were growing up and my marriage was ending in divorce, I began to see all the ways that those losses could transform themselves into a passion for the work and that’s when the writing life became everything to me. Or almost everything: a calling, a refuge, a liberation.  ELISABETH HARVOR'S MOST RECENT BOOK In An Open Door in the Landscape, Palimpsest Press, 2011 Description from Palimpsest Press _In An Open Door in the Landscape, the real and the surreal exist side by side. Doors open on snow, war, influenza, summer and winter oceans, the efficiency of obsession, and men who can dance. In yet another world, on a hot city morning in our most recent century, the tiny industrial screech of insects in August gardens becomes a backdrop for a lovesick woman waiting on a veranda for the postman to bring her relief “in the last era before e-mail, in the last era before high tech gives short shrift to longing.” Other poems shine out of more fleeting events, each poem radiating with the emotional intensity of its moment. “What a gift Harvor possesses. Few write as intensely precise and gracefully spare works.” —The Toronto Star “Dart-accurate poetic observations...” —The Malahat Review “Harvor takes chances in her writing, breathtaking ones.” —Arc |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed