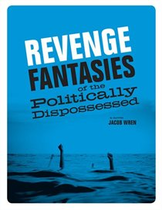

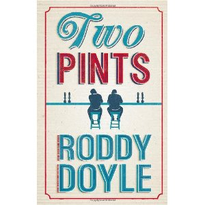

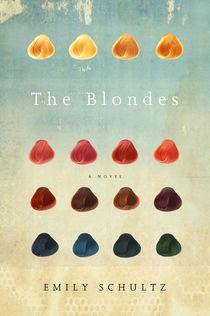

Jacob Wren Jacob WrenPhoto by Brancolia JACOB WREN is a writer and maker of eccentric performances. His books include: Unrehearsed Beauty, Families Are Formed Through Copulation and Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed. As co-artistic director of Montreal-based interdisciplinary group PME-ART he has co-created the performances: En français comme en anglais, it's easy to criticize (1998), the HOSPITALITÉ / HOSPITALITY series including Individualism Was A Mistake (2008) and The DJ Who Gave Too Much Information (2011) and Every Song I’ve Ever Written (2012). He travels internationally with alarming frequency and frequently writes about contemporary art. RUSTY TALK WITH JACOB WREN Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative? Jacob Wren: I don’t know if I have a first memory. But I do know around age thirteen I started suffering from terrible insomnia. Some nights I didn’t sleep at all, while most nights I slept very little. And basically I just filled the endless, sleepless nights with reading and writing, for more or less ten years, until I realized that the simple cure for my insomnia was rigorous physical exercise. Still, to this day, I associate writing with the strange, hallucinatory state that comes from having barely slept for weeks on end, as a kind of unreal trance, almost like a dream. It was during those nights, lying awake, almost too tired to move, that I first trained myself to write. KM: Why did you become an artist/writer and what keeps you going? JW: To be honest, the only thing that has ever really interested me was art (in all its many forms.) I wish I could become interested in something else, since I feel, as a human being, at times this overemphasis on artistic interests makes me a bit narrow, as well as making my interactions with other people often rather difficult. (I mean, I do my best.) At the same time, I find it very hard to maintain any interest in art and often don’t know exactly what keeps me going (except that I have no idea what else I could possibly do). Sometimes I remind myself a bit of this apocryphal story of a Russian who moved to New York but never learned English. Gradually, over the course of his life, he forgot how to speak Russian, yet still never learned English, so in the end he spoke no language at all. Gradually I am becoming less and less interested in art, while not really becoming interested in anything else, so in the end I’m kind of nowhere. Like a priest who has lost faith. But that makes it all sound more dire than it actually is. Still, I think it’s important that we talk about these things, since hardly anyone ever does. I have often said that I don’t particularly relate to people who make performance, or write, or make art, but I do relate to people who make performance / writing / art who think about quitting every fifteen seconds. Those are really my people. I call us the ‘boy who cried wolf set’. Because, for me, if you really look at art today, at what it means, at who it reaches, at what is considered successful or important, it often seems like a complete waste of time. If I had any talent for it, or drive towards it, I would definitely quit art and become an activist, since the world’s problems are now so overwhelming, immediate and tragic. But, for better or worse, I can’t seem to get myself to do anything else: all I can really do is write. (Well, I also make performances, but that becomes harder and harder as the years roll on.) KM: How would you describe your writing process? How does your blog A Radical Cut in the Texture of Reality fit into this process? JW: I mainly feel like I don’t really have a process. I just have ideas and write them down to the best of my ability. Often I try to write every morning, but then, at other times, I am stuck for months on end and write very little. I usually do a first draft in a notebook, and then type it up as I go. Sometimes there is a little bit of re-writing as I type it into the computer, but mainly the second draft just allows me to think more about what I’m doing. I definitely started my blog, in 2005, because I had almost completely stopped writing and was looking for a way to start again. It’s always been difficult for me to get published—I suppose what I write doesn’t quite fit anywhere (maybe it’s a little bit easier now, I’m not sure)—but at the time being able to just post what I was writing on my blog, as I went along, gave me more of a feeling that I was actually doing something. I would tell myself: just write one paragraph and post it, then at least you will have written one paragraph. It kind of made me feel like writing was possible again, after having felt it was basically impossible for many years. (Mainly due to too many rejection letters, or more precisely to the fact that I’m a little bit too sensitive to such things.) Now my blog gets about 2,000 hits a month, so that must mean someone is reading it, but I don’t really have any sense of who is reading it, why, or what they think. There are hardly any comments. I spend so much time on the internet (mainly on Facebook and listening to music), and I know this has deeply affected how I think about art, about writing, and also how I practice it. It is difficult for me to really analyze what this change might be, it has all been so natural and intuitive, but I know there is something about the shuffle feature on iTunes, and about the seeming randomness as one clicks from one link to the next, that has been completely folded into my aesthetic. KM: What or who influences your writing? JW: I keep an ongoing list of favourite books: Some Favourite Books And recently I have added a list of visual artists: List of Artists But mainly I just want to devour everything. I want to have an overview. I want to know what is happening in art today, and everything that has ever happened in art before, and I want to use all of it while at the same time making it my own. I want to speak about the world, about the world today and about history, about ideas, thinking, philosophy, theory, and about my own subjective experiences. I want to struggle with it, admit to failure, be upset that I am not as good as the artists and authors I love but keep trying. I wish the mainstream was more open and more interesting. KM: Can you discuss the relationship between writer and reader or audience? Who would be your ideal reader? I’m interested also in terms of your blog and its readership. Does that audience inform your work in any way? JW: I have a sort of double life, half writing, the other half performing. When you perform the audience is right there in front of you, and all of my performance work is about trying to honestly deal with the fact that the audience is right there in front of me, about the paradox of trying to be yourself in the deeply unnatural situation of a room full of strangers watching you. I’ve always like the Gertrude Stein quote: “I write for myself and strangers.” When I was revising my last book, I showed it to a bunch of friends for comments, and I listened to all of their comments, and later, when the book came out, realized I had completely ignored basically all of their suggestions. I had asked for their help, and then completely ignored everything they said. (Well, I’ve always been stubborn.) And I feel this is so often the way between me and readers, I listen to every comment I get, think about it, try to take it in, fully absorb it, but never directly respond to anything anyone says. Nonetheless, I very much hope it is all in there anyway, somewhere in my head, affecting what I think, how I see what I’m doing, in some completely indirect way making the work better. KM: What is the best piece of literary advice you’ve gotten that you actually use? JW: As I’ve already suggested, I’m so bad with taking advice. But I really liked reading what Alain Badiou once said in an interview. He said the only rule for activism is: keep going. And I guess that’s mainly what I try to do now, keep going, which also means not making too many compromises, trying to offer up something different enough from everything else out there, trying to see the world a different way and put it into words. But, then again, I also constantly want to quit. Which is maybe why the advice is so important. Keep going. KM: What is your favourite or funniest literary moment, if you have one? JW: I actually can’t think of anything at the moment. Hopefully that means there are many favourite, hilarious literary moments to come. Maybe the future will be full of them. KM: What are you reading at the moment? JW: I just started reading The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal by Sean Mills. I believe I must be reading it because I live in Montreal. So far it’s fascinating. KM: What projects are you working on in 2013? JW: I am writing a new book entitled Polyamorous Love Song. Here is a short synopsis: It is a book of many different narrative through-lines. For example: 1) A mysterious group, known as The Mascot Front, who wear furry mascot costumes at all times and are fighting a revolutionary war for their right to wear furry mascot costumes at all times. 2) A movement known as the ‘New Filmmaking’ in which, instead of shooting and editing a film, one simply does all of the things that would have been in the film, but in real life. This movement has many adherents. Its founder is known only as Filmmaker A. 3) A group of ‘New Filmmakers’, calling themselves The Centre for Productive Compromise, who devise increasingly strange sexual scenarios with complete strangers. They invent a drug that allows them to intuit the cell phone number of anyone they see, allowing phone calls to be the first stage of their spontaneous, yet somehow carefully scripted, seductions. 4) A secret society that concocts a sexually transmitted virus that infects only those on the political right. They stage large-scale orgies, creating unexpected intimacies and connections between individuals who are otherwise savagely opposed to one another. 5) A radical leftist who catches this virus, forcing her to question the depth of her considerable leftist credentials. 6) A German barber in New York who, out of scorn for the stupidity of his American clients, gives them avant-garde haircuts, unintentionally achieving acclaim among the bohemian set who consider his haircuts to be strange works of art. And yet each of these stories is only the beginning. And we are also beginning a new, ongoing internet/performance project entitled Every Song I’ve Ever Written. Here is a description: From 1985 to 2004 Jacob Wren wrote songs. Lots and lots of songs. At the time not very many people heard them. Every Song I’ve Ever Written is a project about memory, history, things that may or may not exist, songwriting, the internet and pop culture. On the website everysongiveeverwritten.com you can listen to, and download, these songs. In a way, because hardly anyone heard them, these songs don’t yet exist. If you are reading this, we would like you to consider recording your own version of one of these songs, changing it, making it your own, then sending it to us. We will post every version we receive. There will also be performances and events. Solo performances will feature Jacob performing all of the songs in chronological order (it takes about five hours.) Band Nights will feature a series of local bands in different cities performing one of Jacob’s songs each. After each version, Jacob will interview the band about what it was like to cover the song, and the band will interview Jacob about what it was like to write it. We are not doing this because we think these are the best songs ever (we hope at least a few of them are good.) We are doing this because hardly anyone heard them at the time, and we are wondering if there is some new, strange way to bring them out into the world. In doing so we hope to raise a few questions about what songs mean on the internet, about what songwriting is actually like today, and also take a sidelong glance back at the recent past. LINKS Radical Cut in the Texture of Reality Every Song I've Ever Written PME-ART Tumblr Goodreads Le Quartanier  REVENGE FANTASIES OF THE POLITICALLY DISPOSSESSED Pedlar Press, 2010 Description from Pedlar Press: Set in a dystopian near-future, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed is a novel - a kind of post-capitalist soap opera - about a group of people who regularly attend ''the meetings.'' At the meetings they have agreed to talk, and only talk, about how to re-ignite the left, for fear if they were to do more, if they were to actually engage in real acts of resistance or activism, they would be arrested, imprisoned, or worse. Revenge Fantasies is a book about community. It is also a book about fear. Characters leave the meetings and we follow them out into their lives. The characters we see most frequently are the Doctor, the Writer and the Third Wheel. As the book progresses we see these characters, and others, disengage and re-engage with questions the meetings have brought into their lives. The Doctor ends up running a reality television show about political activism. The Third Wheel ends up in an unnamed Latin American country, trying to make things better but possibly making them worse. The Writer ends up in jail for writing a book that suggests it is politically emancipatory for teachers to sleep with their students. And throughout all of this the meetings continue: aimless, thoughtful, disturbing, trying to keep a feeling of hope and potential alive in what begin to look like increasingly dark times. Revenge Fantasies asks us to think about why so many of us today, even those with a genuine interest in political questions, feel so deeply powerless to change and affect the world that surrounds us, suggesting that, even within such feelings of relative powerlessness, there can still be energizing surges of emancipation and action  Roddy Doyle Photo by Mark Nixon Roddy Doyle was born in 1958. His work includes The Commitments, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha (Booker Prize, 1993), The Woman Who Walked Into Doors, A Star Called Henry, and Bullfighting. His latest book is Two Pints (2012). A new novel, The Guts, will be published in August, in Ireland and the UK, and early 2014 in the USA. He divides his time between Dublin and confusion. RUSTY TALK WITH RODDY DOYLE Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Roddy Doyle: I was about ten, I think, and my teacher, Mr. Kennedy, told the class to write something about a rainy day. This was Ireland, remember, so deep research wasn’t necessary. There were fifty-four boys in the class, and it was the first time we’d been told to write, or compose, anything—to make it up. I wrote about boredom. Mr. Kennedy looked over my shoulder, then read it to the class. KM: Why did you become a writer? RD: I loved reading. I loved football—soccer—but was a hopeless player. I loved music but hadn’t the patience or ability to learn an instrument. But I was literate, so writing seemed like an easy option. I forced myself into the habit, the routine. KM: What is the best writing advice that you’ve gotten that you actually use? RD: Treat it as a job; don’t expect magic. KM: How do you approach revision? RD: If by ‘revision’ you mean editing, I love it. So I approach it with a full heart and a red ballpoint. I tend to, deliberately, write too much. Editing is often a case of paring back. I’m fascinated, and sometimes worried, about how the deletion or addition of a word can alter meaning, tone, everything. When I’m editing, I put all other work aside and concentrate only on the pages I’m editing. I don’t play music, and I often lose track of time. KM: Your books often come out within a few years of each other. Do you work on multiple projects at the same time or stick to one project until it’s complete? Do you have difficultly switching from one genre to the next—particularly from adult fiction to children’s literature? RD: I work on different projects at the same time; I divide my working day, about 9am to 6pm, into chunks. As long as the projects are very different, they don’t tend to infect each other. I play a different type of music for each project. I could, I suppose, change shirts too, but that might be going too far. So, I can work for several hours on a novel, save it, hang out the washing, make a cup of coffee, change the Rolling Stones for Steve Reich, and get working on a treatment for a possible TV series or a book for children. KM: What writers were influential when you first started writing? Who are you reading now? RD: I think Flann O’Brien was important, particularly the Dublin dialogue in At Swim-Two-Birds. E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime was important—the simplicity of the language. I’ve just finished George Saunders’ collection, Tenth of December; I think it’s magnificent. I’m reading a collection of J.G. Ballard interviews, called Extreme Metaphors. It’s great. KM: Given the amount of books that you’ve written, it seems impossible to imagine, but do you ever get writer’s block? And if you do, how do you overcome it? RD: No—never. KM: Do you ever abandon projects? If so, how do you know when it’s time to move on? RD: I’ve never abandoned, but I’ve parked projects for a while, stayed away from them until I was ready to look at them with that mixture of calm and excitement that I need if I’m going to work. Because I work on several things during the day, if one project isn’t going well, I can focus on another. KM: We often talk about the difficulty of rejection for writers but what about the problems that success can bring? After you won the Booker Prize in 1993 for Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, for instance, what was it like sitting back down at the writing desk? RD: Success, however we measure it, is much nicer than rejection. But rejection can be like fuel to an almost empty engine. Rejection is a cousin of determination, and it’s part of the job. Success is too, if you’re lucky. The trick is, I think, to ignore it when you’re at your desk. I never let myself think that, just because I’ve won a prize, I’m not capable of writing shit. After winning the Booker, I couldn’t wait to get back to work. I love the work. KM: You posted your latest work Two Pints, which was just published in its entirety in November, as a serial on Facebook over the last year and half. Why did you decide to do this and what was the process like for you? Did the process have any affect on the end product? In other words, did the reader comments influence revisions? Would you do it again with another project? RD: I wrote the Two Pints pieces for fun. Someone suggested they’d make a good book, so—grand. It’s an accidental book, and still fun. I still write the Two Pints pieces, when the mood hits me and I have time. I often compose them as I’m walking, say, from the city centre, home. I type them up, make sure they’re less than 200 words, then post them on Facebook. I like the near-spontaneity of it—very different from how I normally work. It’s a little madness. I didn’t revise them, so reader comments, while nice, had no influence on them. I’d never be tempted to put work-in-progress up on Facebook. I don’t want to know what readers think until I know the work is finished. KM: What are you working on now? RD: I’ve just finished a novel, called The Guts. It’ll be out here and the UK in August, and the USA early in 2014. I’m writing a short story, about a man who’s injured when another man, in Lycra, cycles into him. I’m also working on a treatment for a possible TV series. ‘Possible’ is code for ‘It’ll never be made.’ I’m enjoying the job. Later this year, a musical based on my book, The Commitments, will go into rehearsal. I wrote the script, the ‘book’, so that will take up a lot of my time. I’m very excited about it. I’m tempted to say ‘I can’t wait’ but, actually, I can—just.  RODDY DOYLE'S LATEST BOOK Two Pints, published by Jonathan Cape, Vintage Publishing, 2012 Description from the publisher: Two men meet for a pint in a Dublin pub. They chew the fat, set the world to rights, take the piss… They talk about their wives, their kids, their kids’ pets, their football teams and--this being Ireland in 2011–12--about the euro, the crash, the presidential election, the Queen’s visit. But these men are not parochial or small-minded; one of them knows where to find the missing Colonel Gaddafi (he’s working as a cleaner at Dublin Airport); they worry about Greek debt, the IMF and the bondholders (whatever they might be); in their fashion, they mourn the deaths of Whitney Houston, Donna Summer, Davy Jones and Robin Gibb; and they ask each other the really important questions like ‘Would you ever let yourself be digitally enhanced?’ Inspired by a year’s worth of news, Two Pints distils the essence of Roddy Doyle’s comic genius. This book shares the concision of a collection of poems, and the timing of a virtuoso comedian. RUSTY TALK WITH EMILY SCHULTZ Emily Schultz Emily SchultzPhoto by Brian Joseph Davis Emily Schultz's first book, Black Coffee Night, was a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Award, while her second, Joyland, received rave reviews. Her most recent novel, Heaven is Small, was a finalist for the 2010 Trillium Award alongside Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, Ian Brown, and Anne Michaels. Her writing has appeared in The Globe and Mail, Eye Weekly, The Walrus Magazine, and several anthologies. Schultz also edits an influential website called "Joyland," which publishes short fiction and commentary from across North America. For this work, she was named one of Canada's digital innovators by Quill & Quire magazine. Schultz lives in Toronto and New York. Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Emily Schultz: When I was in second grade I penned two “books” with hand-drawn covers. I took them in to my schoolteacher and demanded that she read them aloud to the class. One was called The Adventures of Molly Mouse, the other Hemp the Horse. I’m not sure where I’d heard that word, but I thought it made a good name. I guess you could say I started off as a DIY author. KM: Why did you become a writer? ES: I really didn’t feel I had a choice. For example, see above. KM: What influences your writing the most? ES: It varies from book to book. With The Blondes, I guess the contemporary media-scape: the noise of news, disaster, and TV shows like She Survived That … Pregnant?! KM: Could you describe your writing process? (Do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision.) ES: With this book, I wrote the first draft fast, consciously changing my process, which is normally slow and meticulous, weighing every line. My husband and I holed up in a desert cabin for several weeks without internet and that is where I did the bulk of the first draft, writing every day from 9 ‘til 4 while staring out the window at the mountains and desert scrub bush. Strangely, writing quickly I had less structural questions to attack in later drafts, and the characters—although they still needed work—were more consistent. There wasn’t time for self-doubt. KM: Rejection or criticism can often stop new writers before they start. Do you have any advice on how to deal with rejection? ES: Everyone gets rejected. As you become more successful you’re only going to face more or bigger rejections, so you have to get used to it and learn not to obsess. Have a cry, have a drink, watch something stupid on YouTube, and then fuhgeddaboudit. KM: What writers would you recommended to an aspiring writer? Or what writers were influential to you when you first started out? ES: I think you have to find your own writers. I remember when I was young people would tell me, “Oh you simply must read … It will change your life!” and I never seemed to relate to any of those books. I wondered what was wrong with me. And so, although I found writers I related to later, when I was first starting out I tended to write in reaction to work I didn’t care for. I knew more what I didn’t want to be than what I did—but knowing that part actually helped me immensely. KM: What is the best literary advice you've been given that you actually use? ES: Every story must have a beginning, middle, and end—from Aristotle, and my sixth grade teacher. KM: Your funniest or favourite moment that you've experienced as a writer or in the literary world. ES: It doesn’t get any more Canadian than this story. I was in Halifax at a Broken Social Scene concert when a young woman approached me in the crowd. She asked if I was Emily Schultz. She’d read my book and recognized me from a newspaper photo. This was about ten years ago, and it was the one and only time anyone ever recognized me at a non-literary event. I felt like a star. KM: Can you tell us about your new book The Blondes? ES: If this were a Hollywood pitch meeting, my one line would be: Blondes, with rabies. But this isn’t a Hollywood pitch meeting, so I’ll see if I can give a bit more of an impression. Plot-wise, it’s about a grad student who finds out she is pregnant from an on-and-off-again relationship with her married thesis advisor. She’s exploring all these feelings of being bewilderment, not knowing how she feels about him, about her own actions, or if she should keep or terminate the pregnancy, when an epidemic (a virus affecting only blonde women) forces her actions and her fate. I wanted to explore how women both threaten and relate to one another, and at the same time work again in the satirical form. I also wanted the book to be an action-adventure novel for women. KM: What are you working on now? ES: My next novel is still too early to talk about. But I’m doing some screenwriting with my husband Brian Joseph Davis. It’s a TV show about life at an alternative weekly.  EMILY SCHULTZ'S MOST RECENT NOVEL The Blondes, Random House, 2012 Description from the publisher A breakout novel for a young writer whose last book was shortlisted for the Trillium Prize alongside Anne Michaels and Margaret Atwood, and whom the Toronto Star called a "force of nature." Hazel Hayes is a grad student living in New York City. As the novel opens, she learns she is pregnant (from an affair with her married professor) at an apocalyptically bad time: random but deadly attacks on passers-by, all by blonde women, are terrorizing New Yorkers. Soon it becomes clear that the attacks are symptoms of a strange illness that is transforming blondes--whether CEOs, flight attendants, skateboarders or accountants--into rabid killers. Hazel, vulnerable because of her pregnancy, decides to flee the city--but finds that the epidemic has spread and that the world outside New York is even stranger than she imagined. She sets out on a trip across a paralyzed America to find the one woman--perhaps blonde, perhaps not--who might be able to help her. Emily Schultz's beautifully realized novel is a mix of satire, thriller, and serious literary work. With echoes of Blindness and The Handmaid's Tale amplified by a biting satiric wit, The Blondes is at once an examination of the complex relationships between women, and a merciless but giddily enjoyable portrait of what happens in a world where beauty is--literally--deadly. Kathryn Mockler is the publisher of The Rusty Toque.

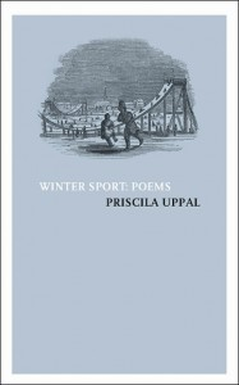

Priscila Uppal Photo by Daniel Ehrenworth Priscila Uppal is a Toronto poet, fiction writer, and York University professor. Among her publications are seven collections of poetry, most recently Ontological Necessities (2006; shortlisted for the $50,000 Griffin Poetry Prize), Traumatology (2010), and Successful Tragedies: Poems 1998-2010 (Bloodaxe Books, U.K.); and the critically acclaimed novels The Divine Economy of Salvation (2002) and To Whom It May Concern (2009). Her work has been published inter-nationally and translated into numerous languages. RUSTY TALK WITH PRISCILA UPPAL Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Priscila Uppal: I remember writing stories about my neighbours. My goal every day was to get myself invited to other people's houses for dinner. I loved watching other people eat and interact with each other. I loved looking through playbins, drawers, medicine cabinets. I was fascinated by people's parents, what they deemed acceptable behaviour or not, what they made for dinner, what gods they worshipped. I honestly think I became a writer because I was pretty nosy about my neighbours. KM: Why did you become a poet? PU: Because I didn't know it was something I could be. I read lots of poems and felt at home inside the language of poetry—metaphor, ambiguity, utterance. Then I started writing them. I wrote poems as a teenager almost every single day, and I haven't really stopped. I went to university because I soon learned that I could actually get scholarship money to read and write poetry and other books all day. That seemed too good to be true—criminal even. So, I took advantage of it. And I suppose I still am. KM: Could you describe your writing process? (Do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.) PU: I probably do engage in writing every day but the type varies. I write poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction, plays, essays, articles, lectures, even interviews. I tend to write in one form while I am editing another. This kind of cross-pollination, I think, keeps my brain firing in interesting ways. I always work on more than one project at once. That way if I'm stuck or bored, I will switch to another project until I figure a few things out and can return with renewed energy. KM: Rejection or criticism can often stop poets before they start. Do you have any advice on how to deal with rejection? PU: I listen to criticism if it comes from a trusted or intelligent source. I then try to figure out if I think it's fair or valid or something to ponder while I write other work. But I don't listen to rejection. If a magazine or publisher doesn't want my work, that's fine, then it's not the right place for the work. Sometimes the hardest part of publishing is figuring out where a piece will find a home. If you consider that phrase "finding a home," it's apt because if you're someone who knows what it's like to be on your own (I left home at 15, and so know this quite well), then it doesn't seem strange that you might not find the perfect place right away. KM: What poets or writers would you recommended to an aspiring poets? Or what writers were influential to you when you first started out? PU: I think it's hard to sort through all the stuff out there. Every aspiring poet probably already has some favourite poets, so I might suggest finding out who those poets read and liked and who they were reacting against to get a sense of how a poet works within the world of poetry. I think it's important to read widely and internationally and that if you don't have people in your circle who can recommend writers that might be of particular interest to you in terms of what you might already be writing and reading, then taking a class can help draft a new reading list and bibliography. I discovered lots of writers through taking courses and those teachers recommending more writers to me. KM: What is the best thing about being a writer and what is the worst thing? PU: The best thing about being a writer is that I can work almost anywhere. My favourite place to work is beachside in Barbados. I write for hours in the morning, then run on the beach, then make notes and read all afternoon and swim. I can't think of a better life than that. The worst thing about being a writer is that everyone asks you what you really do for a living. I was hired by the university as a poet. I teach poetry and other arts. I tell people that I might not make all my money through book royalties, but I do indeed make my living as a writer KM: Your funniest literary moment, if you have one. PU: One of the funniest was in Sri Lanka at the Galle Literary Festival (a wonderful and warm festival by the way, in a beautiful old Dutch fort town). The opening reception was on this glorious property on a hill and sponsored, in part, by the government of Sri Lanka. As we walked in, young Sri Lankan boys played bagpipes, dressed in Scottish outfits. An orchestra of other young people in elaborate school uniforms played on the grass. Champagne flutes of lime juice were passed around and plates of warm nibbles. At the end of the reception, as we were to talk to the next venue for the evening, further down the hill, a flurry of fireworks exploded. They were so unexpected and near to us that many of us screamed, held our hearts, and tried to steady ourselves as we laughed in both amusement and fear. The fireworks kept coming. Louder. Closer. Bits of fire fell directly in front and behind us the entire time. In order to contain our fear, many of us laughed, and kept laughing. When it was finally over, we writers all looked at each other in relief, trying to figure out if this was the usual welcome for writers for the festival. KM: What are you working on now? PU: I'm just about to leave for London to resume my position as Canadian Athletes Now Poet-in-Residence during the 2012 Olympics and Paralmpics. I'll be writing and publishing two poems per day, one on the Canadian Athletes Now website and one on the Literary Review of Canada website (under Poet's Corner). I will also be posting an article every two days on the LRC website about sports art. This is a project I am very passionate about—encouraging sport and artistic practice, breaking down stereotypes between the sports and arts worlds, and bringing poetry to new audiences in a fun and exciting way. I will be working on the companion to Winter Sport: Poems, called fittingly Summer Sport: Poems, to be published in early 2013. Follow Priscila Uppal |

| Excerpt from "Dominoes" I didn't really mean to drop out of school. When I started at the university I thought learning how to name and explain things might bring me purpose, lucidity. I attended lectures and turned in my papers on time. I stood dead in the centre of the swirl and storm of theory. I applied myself. But then I started going to the student-operated pub between, and sometimes during, classes. The pub was difficult to find; it was located in a catacomb next to the cafeteria, and if a person wasn’t careful she could end up in the boiler room or the yearbook office. Still, it was worth it once I arrived. I spent whole days sitting in one of the vinyl chairs, their shiny purple backs stapled like patchwork beetles. I went into the pub with every intention of leaving, my time parcelled out efficiently, a half-pint of beer resting modestly on the rickety wooden table in front of me. But when the time came for me to get up and walk the short distance up the stairs, out the door and across the quadrangle, I stayed sitting, less paralyzed than somehow anchored to my surroundings. And then it always seemed too late. Too late to do things properly. Too late to do anything but wait for the next song to come on the radio. Sometimes a voice less disapproving than bewildered would intrude on my whiling away of the hours. What are you doing here, it would ask, then wait patiently. I’m biding my time, I’d reply softly, humbly, I’m biding my time. It doesn’t feel as if I’ve dropped out, really. I still have library privileges, and the seventy-five-dollar cheques from Mum (for sundries, she actually wrote in one of her cards) keep coming every month, or more often if she can manage it. Now I’m taking this evening course, a writing workshop, so that one day, if I have what it takes, I will be a real writer. My instructor has the best posture I have ever seen. Every day I watch her riding her bike away from the recreation centre, and am convinced that there is nothing but willpower and gravity anchoring her bum to the broad, black reupholstered seat. She scares me a bit, like helium balloons. Our last assignment was to choose a clear, quirky, luminous incident from our pasts and to build a story from there. I got a letter from Mum the other day, and in it she enclosed this clipping from the newspaper about your buddy Richie. The article wasn’t very long. There wasn’t much to tell – a bit about the murder, the arrests, how it shocked the community. And then the punchline, like something from a TV movie: Richie, two months short of a chance at parole, six years into his sentence, had hanged himself in his cell. So sad, Mum wrote. And she asked me the questions she could not ask you: Remember his mother, Mrs. Henley? Did you ever discuss with Jeremy what happened with Richie? Such a tragedy, wasn’t it? I wanted to call Mum to talk to her about it, but I didn’t because she doesn’t know I dropped out. I wanted to call you to talk about it, but we don’t really talk. So I started thinking maybe this was a story. It happened in High Park, at nighttime, and there were three of them with baseball bats. When you think about it, you might think of a crack, wood on bone, something clear and conclusive. But I know it was a thud, soft and stupid. Spiro was kicking him and yelling something about one less faggot, and looking at Richie like he was chicken shit, so Richie took the bat and brought it down on the guy’s chest, and then he couldn’t stop himself; he just kept swinging until he stopped the ouf noise. It was then he noticed the lines of blood streaming out of the ears like two solemn ant processions. But Joey still went at it, even after Richie and Spiro had backed off. When Joey finally stopped, it was like the guy on the ground wasn’t even a person anymore. He was just this mess of rags and blood and arms and legs all quiet like sleeping animals, so they ran back to the car and they drove away. On the back seat was a two-four of empties Richie meant to return for the deposit money the night before, and on the dashboard an old air freshener Lori had bought him. Spring Rain. Fucking hell, said Spiro. That thing smells like shit. Richie’s life had always run alongside ours, like a wild horse next to a train. We were steady, on schedule, simply because he was not. |

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of being creative (writing, art making, etc.)?

Brian Joseph Davis: I saw a documentary on special effects when I was 7 and attempted to make my Kermit the Frog doll "animatronic" with old bike parts. Without the stuffing, and full of bike brakes, I thought he he looked deflated so I filled it toothpaste. That looked messy so I then attempted to "set things" by putting it in the freezer. I forgot about it there until my mom found a gutted Kermit the Frog doll full of gears and toothpaste.

KM: How would you describe conceptual writing to someone unfamiliar with the genre?

BJD: It's an umbrella term, but I'd say it's any writing with a formal concern--writing that starts from a certain point or a set of rules, almost like a game. That could include anything from Beckett to a Saturday Night Live parody.

KM: How did you first get interested and involved with conceptual writing?

BJD: I was creating this kind of work coming out of media art, with my inspirations being all over the map: JG Ballard, Kathy Acker, artists who work with text like Fiona Banner, Jenny Holzer. Little did I know that people like Darren Wershler or Ken Goldmsith on the East Coast, or Vanessa Place on the West Coast, were codifying conceptual writing. Their hard work has made it easier.

KM: How would you describe your art/writing practice/process?

BJD: When I do this kind of work I'm really looking for a kind of database of text. A good chunk of information that hasn't been exploited beyond its original use yet.

KM: What artists/writers/poets would you recommended to someone aspiring to be an experimental or conceptual writer?

BJD: I kind of hesitate to suggest a canon because this genre is a genre of practitioners. Like cheese making you only learn by doing so I'd suggest, find an idea and do it. Start with queso fresco.

KM: What is your funniest literary moment?

BJD: I was presenting "Johnny" in LA a couple of years ago, and afterwards a woman came up to me and said, I think you used lines from a script I wrote.

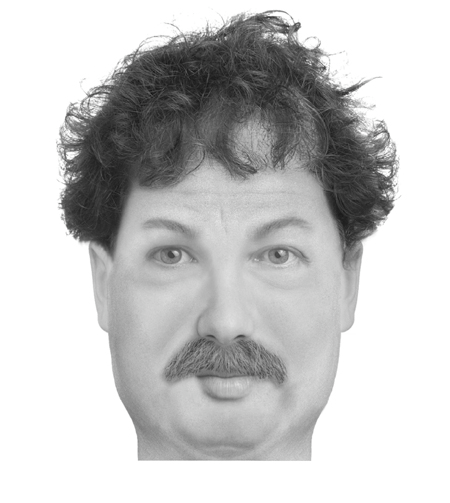

KM: Your recent Tumblr project The Composites in which you create images "using law enforcement composite sketch software and descriptions of literary characters" is getting a lot of media attention. Why do you think that is?

BJD: In North America, technology and culture have been in a 10-year sprint to forensicize everyday life far beyond the need of basic law enforcement. Internationally, of course, that has been the case much longer with Europe especially having to negotiate surveillance culture for decades. I’d also say that the combination of a law enforcement media and literature is a snapshot of inner space right at a time when literature is experiencing an ontological crisis. Writing’s struggle with digitization emulsifies well, it seems, with technology’s struggle with issues of privacy and security.

KM: What are you working on now?

BJD: Thank god, nothing.

Ignatius J. Reilly, A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole A green hunting cap squeezed the top of the fleshy balloon of a head. The green earflaps, full of large ears and uncut hair and the fine bristles that grew in the ears themselves, stuck out on either side like turn signals indicating two directions at once. Full, pursed lips protruded beneath the bushy black moustache and, at their corners, sank into little folds filled with disapproval and potato chip crumbs. In the shadow under the green visor of the cap Ignatius J. Reilly’s supercilious blue and yellow eyes looked down upon the other people waiting under the clock at the D.H. Holmes department store, studying the crowd of people for signs of bad taste in dress. (Multiple suggestions) Updated image: Many readers believed that Ignatious weighed significantly more than the original composite implied. |

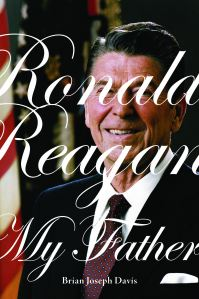

Ronald Regan, My Father, ECW Press/Independent Publishers Group, 2010

Description from ECW

“An elegant, wise-ass rush of truth, hiding riotous social commentary in slanderous jokes…It almost feels like he’s leading a palace coup.” – Spin Magazine on Portable Altamont

“Davis’ brilliant media deconstructions are pointed and hilarious at the same time.” – Kenneth Goldsmith

“The book of your fever dreams.” – Slate on I, Tania

The elderly take to the streets at night for illegal and cathartic electric scooter racing. (Think Two-Lane Blacktop but starring Abe Vigoda and Estelle Getty.)

A copy editor suffers brain damage from West Nile virus and is suddenly filled with cannibalistic violence and award-winning minimalist poetry. (It’s a little like Awakenings, but directed by David Cronenberg.)

Mayor McCheese visits a sexually repressed British couple in the early 1970s and touches their lives forever. (Okay, try this: Pasolini’s Teorema but with Mayor McCheese.)

A Texas doctor transplants the mind of a meth-addicted convict into the body of a suburban web developer, resulting in America’s first “death-penalty case that turned into a custody case that turned into a right-to-die case.” (It’s like a hole drilled in your head and five HBO original movies poured in all at once.)

Startlingly original but anchored by vivid characters, Ronald Reagan, My Father weaves all these ideas, and more, into a bleakly hilarious vision that’s both human and uncanny – as if Raymond Carver was marooned on Mars with ten hours to live.

Photo by Andrew Chowmentowski.

Her first novel, Excessive Joy Injures the Heart, was named one of the ten best books of the year by the Toronto Star in 2000, and her most recent story collection, Let Me Be the One, was a finalist for the Governor General's Award. Her first book of poetry, Fortress of Chairs, won the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for 1992. An Open Door in the Landscape, her third book of poetry, was released in September 2010.

RUSTY TALK WITH ELISABETH HARVOR

Kelli Deeth: How do stories and poems come to you?

Elisabeth Harvor: The music of certain lines comes to me—and keeps coming to me—like a line of a song or poem remembered, but it's a beat that isn't consciously from any song or poem I’ve ever read or heard. So this is how a story or poem begins. With poetry, the opening line can sometimes sound like a maxim with self-deprecation in it. Take the beginning of the poem called "I Am A Scientist" which begins with the words

Like all paranoids, I am a scientist

Dark Cause + x = Predestined Effect,

that is, if someone doesn't like someone, namely x

and if x = me, then I'm turned into a sleuth

in the name of survival...

I can't see these lines as the opening of a story, they are too rhythmic, too insistently declarative.

Another example of opening lines that feel as if they need to become the beginning of a poem—and only a poem—are the opening lines of "Island of Illness":

All winter long this has

been lying in wait for you,

island of illness,

lap of warm waves at your pillow...

This doesn't at all sound like the opening of a story to me either, and although I can't swear that I changed the first-person voice into the second-person voice because I didn't want the poem to have too much self-pity in it, it does seem to work best in the second-person voice. And why is this? Because the second-person voice feels, paradoxically, both more intimate and more universal.

The openings of stories or novels, on the other hand, are usually more languid. I can feel the story-telling impulse when I "get" the first lines. Take the opening of a story called “Love Begins with Pity” in Let Me Be the One, a story in which a poet in her thirties falls more than a little in love with a young man who's a student in a series of high school workshops she is leading:

"Why are you laughing?" she asked them. She even smiled at them a little although falsely, surely, for she was feeling damp from apprehension.

KD: How would you describe your approach to revision?

EH: I value it. It's a purge and a freedom and a benevolent addiction. It’s also a second chance. Or a whole series of second chances, and as time goes by, I'm more and more grateful for second chances. But my approach to these second chances? It's often a matter of delete, delete, delete, especially when revising poetry. But it's a question too: Have I made the best emotional use of the space on this page? And also: Have I gone deep enough here?

KD: Your work is very honest. Do you think emotional honesty in a story, poem, or novel is absolutely essential?

EH: I do, but this conviction doesn't appear to rule out the occasional enjoyment of fictional inventions, fabrications, and lies. As both a writer and a reader, though, I prefer those moments when the surreal enters the real and does it naturally, without show-offy artifice.

KD: What other writers inspire you? How do they inspire you?

EH: Woolf’s To the Lighthouse for its mesmerizing voice, for its profound understanding of childhood, and for the depth and complexity of its emotion; The Journals of Sylvia Plath for its joie de vivre and its brilliant fury; William Carlos Williams for "The Ivy Crown;" one of the great love poems of all time; Penelope Mortimer for her authentic evocation of depression and the fierce economy of The Pumpkin Eater; Saul Bellow for the deep anguish and comedy of Seize the Day; Bernard Malamud for the inspired comic originality of A New Life; Paulette Jiles for the stomach-dropping drama of "Night Flight to Attawapiskat;" Grace Paley for "A Conversation with my Father," a terrific story about writing a story; Marian Engel’s tender ode to a bear in Bear; Nadine McInnis’s fetching (if frustrated) mother in "Legacy," and almost every poem in Plath’s extraordinary Ariel. As well as the work of so many other writers.

KD: What would you say are the rewards and challenges of a writing life?

EH: The challenges are a big part of the pleasure of throwing yourself into the work. When I was younger, though, I resented any suggestion that anything I wrote might benefit from revision. I couldn't bear to tamper with what I saw as perfection! Back then, so-called real life also took so much of my attention away from my writing life, but once my children were growing up and my marriage was ending in divorce, I began to see all the ways that those losses could transform themselves into a passion for the work and that’s when the writing life became everything to me. Or almost everything: a calling, a refuge, a liberation.

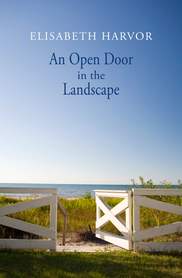

In An Open Door in the Landscape, Palimpsest Press, 2011

Description from Palimpsest Press

_In An Open Door in the Landscape, the real and the surreal exist

side by side. Doors open on snow, war, influenza, summer and

winter oceans, the efficiency of obsession, and men who can

dance. In yet another world, on a hot city morning in our most

recent century, the tiny industrial screech of insects in August

gardens becomes a backdrop for a lovesick woman waiting on a

veranda for the postman to bring her relief “in the last era before

e-mail, in the last era before high tech gives short shrift to longing.”

Other poems shine out of more fleeting events, each poem

radiating with the emotional intensity of its moment.

“What a gift Harvor possesses. Few write as intensely precise and gracefully spare works.”

—The Toronto Star

“Dart-accurate poetic observations...”

—The Malahat Review

“Harvor takes chances in her writing, breathtaking ones.”

—Arc

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed