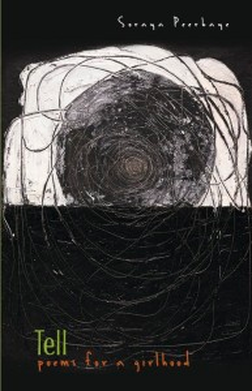

RUSTY TALK WITH SORAYA PEERBAYE Soraya Peerbaye’s first collection of poetry, Poems for the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names, was nominated for the Gerald Lampert Award. Her poems have appeared in Red Silk: An Anthology of South Asian Women Poets; she has also contributed to the chapbook anthology Translating Horses. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph. Peerbaye lives in Toronto with her husband and daughter. Tell: poems for a girlhood is also a finalist for this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize, to be announced June 2, 2016, in Toronto. The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. [...] I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered. Phoebe Wang: I’m always interested when I read work that addresses traumatic events and difficult emotional terrain. What was the motivation that brought the writer to take on this task? What about the cruelties of girlhood and the murder of Reena Virk offered itself up as an impetus to write poetry? Soraya Peerbaye: My desire to write about the murder of Reena Virk crystallized after the first conviction of Kelly Ellard was overturned and the second trial was set. The media had framed the case as an example of the rise in “girl violence,” as though the potential aggression of girls and women was a new phenomenon, without recognizing the social hierarchies of race, gender and beauty norms that made girls like Reena so intensely vulnerable. Then it seemed that the legal system could not believe in the guilt of a young, white girl. So the first impetus was political; I wanted to speak to the chasm between those public discourses, and the experience of so many women of colour I knew—those of us who had made such delicate transactions in girlhood to stay out of harm’s way. As for the poetic—that was a response to the trials themselves. I think anything direct I might have wanted to say was undone by what was unknown, uncertain, denied. By the fact that the young people who testified had so few words to describe Reena herself, her struggle to survive. Even in describing themselves, what they’d done, they couldn’t speak in an embodied way of their own memories. There were salient elements that the trials couldn’t hold because they weren’t directly tied to questions of guilt or motive; yet these were the moments that the witnesses seemed to awaken, to quicken. There was a profound sense that we, as a culture, were dredging for something, and at the same time eroding it; that the telling and re-telling was creating a crisis not only for the trials and a potential verdict, but also for the lives of these young people and Reena’s memory. Poetry felt like a way of holding these truths and lies, memories, omissions, silences, with regard for the valence of all of it. PW: Did you look to other elegiac poems or any other works that dealt with grief for examples and guides, and if so, what were they? SP: Carolyn Forché’s Blue Hour and her anthology Against Forgetting were early inspirations. Other collections I looked to with more intent were Marlene NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and Sachiko Murakami’s The Invisibility Exhibit. I was riveted by their sustained attention to terrible events; with the way they worked with documentation, testimony; race and gender and law; with the lack or loss or disintegration of memory and artifacts; with time. In Murakami’s work, it was also the way she carried that event in her daily life—what seemed innocuous in the ordinary world, and the way it was tainted by the trauma she was carrying. I’m not sure how much elegy and grief were the driving questions. I didn’t know Reena; it wasn’t my grief. It was more about endurance, maybe closer to vigil. I also read Steven Ross Smith’s Fluttertongue 4: adagio for the pressured surround. It’s an annotated vigil; there’s a violence in its lyricism, in the tension and release between memory, a contemplation of the political, the act of tending to the beloved during a prolonged dying, and the quotidian. I feel the influence of that collection in the Gorge poems in Tell. PW: Tell’s five sections seem to me to have a kind of circular motion. As a reader, I felt like I started on the outer rim, was sucked into the dense and dark centre, and then was whirled out again. How did you find the arrangement and shape of this manuscript? SP: I was searching for that shape and energy for a long time, but really only found it in the process of revision with Beth Follett, for which I am very grateful. It needed to be released from chronology, from the sequence of events, the process of ascertaining guilt or innocence. I knew from the beginning that this wasn’t a murder mystery; if Ellard had been acquitted, it wouldn’t have changed the book significantly—the material might have been flung further apart, but still by the same physics. I think the manuscript works through the turn and return around the same events. The narrative isn’t stable; each turn has the potential to complete a narrative but more so to disturb it—to create other currents, other pools. Circular, yes. Coming to the verge of something and then whirling outwards. It bears repeating how many trials there were related to the case—from the trials of the young girls charged with aggravated assault, to the trial of Warren Glowatski, to the three trials of Kelly Ellard. I think of it more as a spiral; the witnesses circle around the same questions but at different points of their lives: 13, 15, 19, 21, 27...their lives are changing but tethered to the same forces and the same questions of who they were. PW: I felt the speaker in these poems questioned racialized experiences and violence without ever expecting to come across a satisfying conclusion. Was that tension deliberate? Did you set out to create a feeling of open-endedness? SP: Yes and no—it wasn’t so much an intent, but I did want to map it as I experienced it. At the heart of the collection is the girl I was. I had no language as a child, or even as an adolescent, for my experience of race or racism. Finding those words changed the experience and gave me a different capacity to bear it. I admit I wish I had the assuredness of other poets, who can channel both the tenderness of who we were, and the rage, personal and communal, of our present recognition of that. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is foremost in my thoughts as I write this—the kineticism of her writing emerges from her naming of things through every kind of language that she has, lyrical, critical, activist... and the way those languages catalyze each other. Law looked for an explicit motive and a binary delineation between the accused and the victim. My dear friend, scholar Sheila Battacharya, once commented on the Reena Virk case as an event “that has no motive but is not neutral.” It’s that I’m trying to get at; the feeling of it being charged with racism, and for that matter with cruelty towards big bodies, androgynous bodies. It’s charged and we feel it but can’t hold it. We don’t often describe the Reena Virk case as a gendered crime, in the way it enforces white feminine hegemony—but it is that, too. PW: Similarly, although Reena’s attackers were tried for the crime, there’s a sense of another trial that involves the reader and viewers of the event, as well as all Canadians who are unknowing or who stand passively by when bullying takes place. There’s a sense of culpability that can’t quite be washed away. How did you explore the idea of trial and guilt in your writing process? SP: I think that unlocking questions from the legal proceedings allowed me to consider, what exactly is being asked here? Who do we believe, who do we want to believe and why? One of the statements that didn’t find its place in the manuscript was a riposte by Ellard when she was first questioned by police: “This is Victoria. No one gets murdered in Victoria.” I kind of laughed when I read it—it’s such a bitchy and astute play—a comment on the mindset before the finding of Reena’s body. I was struck in the trials by the power plays in the courtroom language; how the young witnesses tried to be more formal, in their language and tone, to regain authority over their own memories or claims of truth. The way their voices dropped, their stammering, was so often taken as an indicator of unaccountability, lying or even just dumbness. I wanted to examine the fairness of that, and at the same time undermine the brutal formality of the courtroom in the face of the witnesses’ experience, the authority of adulthood, of prosecution; to reveal what felt like a kind of vulnerability on the underside of the questions. And at the same time there were entire series of examinations and cross-examinations in relation to moonlight, tide, mud, shooting stars—and no one, neither adult nor child, is accountable to the natural world; they talk about it without seeing it. PW: Can you talk about the difficulties of working with these source texts—the autopsy reports, the testimonies, and any other texts? Was it similar in some ways to writing a found poem? SP: The source texts were always alive and full of potential for me. “Examination” was probably the only poem I consciously thought of as a found poem. Otherwise, I was trying to intervene more actively with the text, even when the intervention was about creating a relationship between the source, and silence, or unanswerability. There’s a process of critique that is continuous and shifting: sometimes I am questioning, but oftentimes the source unintentionally subverts or asserts itself. But I guess that’s what a found poem does. I’ve been thinking about the term ‘rewilding,’ and wondering if what I was responding to was a sense that the legal proceedings were domesticating a discourse around young people, violence, contempt... I turned to archaeological texts, or my conversations with Cheryl Bryce’s words as Lands Manager for the Songhee First Nations, because it reimagined the ecology of Victoria; an antidote to the domesticated way of describing the city’s beauty, the shock that such a terrible crime could have happened in a such a place, a “tea-town.” There is a desire for me to rewild the testimony, to return it to a larger ecosystem, beyond the trials and the verdicts. PW: The book’s middle section about your own family, identity and girlhood, actually brings the reader closer to understanding and visualizing the invisible details of Reena Virk’s life. Did you hope to bring the reader into spaces that they might not usually venture? SP: It’s good to hear that. I hesitated to write about myself; I didn’t want to suggest any equation between my experiences and Reena’s. But it became necessary to remember how hard I wanted to be seen; to have that touchstone, even if I couldn’t offer anything of Reena’s life before the night of her death. There’s guilt for me in this section—that I’m writing this from such a privileged position. I don’t know what I hoped that the reader might feel in relation to my life, except maybe that tension; the difference between the strategies I could use and Reena’s. That I tried so hard to be a good girl, while Reena transgressed. The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. She pissed them off, royally. Shoilee Khan, writer and director of the Bluegate Reading Series in Mississauga, told she remembered being in grade seven and poring over every newspaper article, “enthralled” at the strength of Reena’s desire and her daring. I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered. Tell: poems for a girlhood |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed