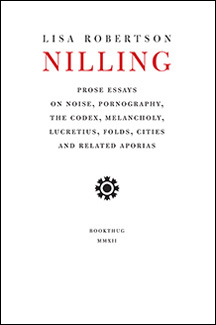

Lisa Robertson For many years LISA ROBERTSON has worked across disciplines and often in collaboration. With the late Stacy Doris she was the Perfume Recordist, an ongoing sound performance and writing project with work in the new I'll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women. She worked as The Office for Soft Architecture, publishing reports, essays, walks and manifestoes as well as curating and cooking as OSA. Currently she is translating the French linguists Emile Benveniste and Henri Meschonnic with Avra Spector. Her most recent book of poetry is R's Boat, from University of California Press, and Bookthug published a new book of essays, Nilling, in spring 2012. She lives in rural France, and teaches at Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam. RUSTY TALK WITH LISA ROBERTSON Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively or being creative? Lisa Robertson: I think my earliest creative acts were acts of deception and truth bending—petty theft, rebuttal, cover-up. This led directly to writing. KM: Could you describe your writing process? (For example, do you write every day? When? Where? How do you approach revision, etc.) LR: Everyday I sit in an armchair and write in a notebook as I read. If somebody gives me resources I leave the armchair and travel to read in an exotic library. Writing on trains and airplanes on the way to and from these libraries is a special pleasure, because so much anticipation and repletion is involved. Talking to my friends usually shows me how to work with the material I have gathered. My dearest friends are the ones I simply obey. KM: How would you define experimental writing? LR: I wouldn't define experimental writing. It would cease to be experimental then. KM: What influences your work? LR: Unanswerable questions. Unanswerable to me that is. Right now I am trying to understand the movement a triangle sections, and I am trying to understand the humoural system of medicine. Put more simply, desire influences my work. KM: What have you read recently that excites you? LR: I just spent a month reading at the Warburg Institute in London, for 6-8 hours a day, six days a week. Everything excited me. I was reading about the relationships between geometry, astronomy, optics, and medicine in the ancient world, until the baroque era and Johannes Kepler's work on the elliptical orbits. I wanted to understand the dynamics of the ellipse, and I wanted to understand science as a relational query into the structure of the cosmos, rather than a recitation of the mechanics of cause and effect. Plato's Timeaus is hallucinogenic in that respect. So is Kepler's The Six-Sided Snowflake. So is medieval Arabic optics. These studies are enticing me to draw more, and that is a pleasure. In terms of recent poetry—Erin Moure's translations of Galician poet Chus Pato, Aisha Sasha John's new work, Angela Carr, the American poet Chris Nealon, and Francis Ponge. I read Ponge as a contemporary. KM: What is the best piece of writing advice you've heard or been given that you actually use? LR: Writing is the good use of boredom. I try to have a boring life. I don't socialize, and I eat nine servings of vegetables a day. KM: Your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one. LR: When Jam Ismael read at KSW in 2002 she sat a tape recorder on a windowsill and played a cassette recording of New Delhi crows. Vancouver crows came to the open window to listen and respond. Every emotion cracked open at once. KM: What are you working on now? LR: I am simply reading and learning, and making the occasional paragraph or drawing as record and exploration.  LISA ROBERTSON'S MOST RECENT BOOK Nilling, Bookthug, 2012 Description from the publisher: Nilling: Prose is a sequence of 6 loosely linked prose essays about noise, pornography, the codex, melancholy, Lucretius, folds, cities and related aporias: in short, these are essays on reading. Excerpts from Nilling: EXCERPT 1 I have tried to make a sketch or a model in several dimensions of the potency of Arendt's idea of invisibility, the necessary inconspicuousness of thinking and reading, and the ambivalently joyous and knotted agency to be found there. Just beneath the surface of the phonemes, a gendered name rhythmically explodes into a founding variousness. And then the strictures of the text assert again themselves. I want to claim for this inconspicuousness a transformational agency that runs counter to the teleology of readerly intention. Syllables might call to gods who do and don't exist. That is, they appear in the text's absences and densities as a motile graphic and phonemic force that abnegates its own necessity. Overwhelmingly in my submission to reading's supple snare, I feel love. EXCERPT 2 In the facsimile Oblongus Codex, at the bottom margin on the page containing lines 1140-1159 of the fourth book of De rerum natura, I saw what at first appeared to be the photographed image of a small oval hole about the size and shape of my thumbnail, tidily cut from the vellum of the original. Bordering this ellipse, I saw a faint drawing that added a labial ornamental border around the shape. It seemed that some sort of monkish pornographic doodle had been censored. At closer examination I realized that the elliptical absence had in fact not been cut from the page by some historical censor--it was rather a flaw inherent in the structure of the vellum; the trace of a wound perhaps. Several of these photographed images of material mise-en-abimes appeared as I leafed through the codex. In each case the page was cut from the larger skin so that the scar found its place in a margin, so as not to interfere with the scribe’s work. But here in book four, the scribe had decorated the flaw in the skin with this mildly and endearingly erotic doodle. The tiny absence was animated: a lacework. Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed