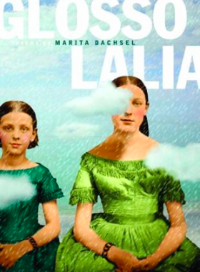

Marita Dachsel Marita DachselPhoto by Nancy Lee Marita Dachsel is the author of Glossolalia, Eliza Roxcy Snow, and All Things Said & Done. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and the ReLit Prize and has appeared in many literary journals and anthologies, including Best Canadian Poetry in English, 2011. Her play Initiation Trilogy was produced by Electric Company Theatre, was featured at the 2012 Vancouver International Writers Fest, and was nominated for the Jessie Richardson Award for Outstanding New Script. She is the 2013/2014 Artist in Residence at UVic’s Centre for Studies in Religion and Society. RUSTY TALK WITH MARITA DACHSEL Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Marita Dachsel: My mother was an elementary school teacher, and grade one was her favourite to teach partially because she got to teach kids to read and write creatively. She did a great job instilling the importance of both in me, and I know I was writing creatively thanks to her long before my first true memory. When I was around five I wrote and illustrated a collection of stories about horses called…wait for it…Horse Stories. I remember spending longer on the illustrations than the stories, and I think the illustrations came first. My parents’ living room is very gothic—red carpet, red velvet curtains, dark beams, huge heavy-glassed lights that look medieval in inspiration, a fireplace, and a menagerie of taxidermied animals and birds along one wall. But it’s the room that gets the most natural light. I remember writing one of the stories on the carpet, the sun warming my body, crayons beside me, the television on as it always was (I can’t remember the show, but Dukes of Hazard is my default childhood memory show). I was so proud of my work. I still have it. KM: How did you become a writer? MD: I always wrote. When I was in elementary school one of my goals was to be a writer when I grew up (along with fire fighter and architect, so take that for what it’s worth), and while I continued to write as I got older, it didn’t really seem like something that could be real. Then I went to college with a vague idea that I might become and English professor. There I took my first creative writing class, amazed that this was possible. I loved it. My first published poem I wrote in that class. Then I learned you could do a degree in it at UBC, so I transferred and ended up doing both my BFA and MFA there. Despite this, being a writer feels both like something that I just happened to become and something that I’ve always been. KM: What writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now? MD: Just before I took that very first creative writing class, I was in a John Steinbeck and John Irving phase. Then I discovered Canadian writers and women writers. Reading Canlit felt revolutionary. Margaret Atwood, Barbara Gowdy, Carol Shields. Anything and everything in my Canlit anthology seemed to be a springboard. Now, I don’t have enough time to read everything I want to read. So many novels, poetry collections, essays, short stories, memoirs I want to read. Right now, I’m reading Brenda Shaughnessy’s Our Andromeda, Steven Price’s Omens in the Year of the Ox, Amanda Leduc’s The Miracles of Ordinary Men, Ann the Word: The Story of Ann Lee, and what feels like a million various poems and anthologies for the poetry class I’m teaching on poetic forms this fall. I’ve been itching to start Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, but I’m going to wait for the right weekend to devour it. KM: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process? MD: My process for poetry varies a lot depending on the poem, what was its initial impulse, where it came from. I scribble lines in a notebook, return days, months later and build off a line or an image. Then cut, slash, and rebuild. With the poems in Glossolalia, so much was dependant on finding the right voice and shape. I’d research, make notes, write a draft. If the voice wasn’t right, I’d move on to the next wife. But if I felt like it was close, I’d start shaping the poem, writing more and more, then hack it to pieces, rewrite, hack, rewrite until it all sounded and looked right. Then I’d come back to it in a year or two. If it still felt right, great. If not, back to the beginning of the processes. KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one? MD: When my eldest was a baby, I read him Oliver Jeffer’s Lost and Found many times a day. It was a family favourite and when I got to the part where [spoiler!] the penguin and the boy are reunited, I would hug my son and say “A big hug for the penguin, a big hug for the boy, a big hug for you.” One day when he was about 18 months, he was “reading” the book by himself on the floor of our living room. I spied him from the kitchen. He turned to the hugging page and he hugged the book. It still makes me a little misty remembering that moment. KM: Your second poetry collection Glossolalia, is a series of monologues spoken by the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith. How did you come to the premise of this book and what drew you to the subject matter? MD: I’ve always been interested in fringe religions, and a few years ago the FLDS in Bountiful, BC was in the news. I was curious about their tenet of polygamy and discovered that it was first introduced into the Mormon Church (of which the FLDS are a breakaway sect) by their founder Joseph Smith way back in the 1840s. I wondered about the women, how they must have reacted when faced with a concept so alien to the society in which they lived, to the culture in which they were raised. I wondered how I would have reacted. I love research and can get obsessed about a subject quite easily. I found two great biographies on Smith’s wives: In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith by Todd Compton and Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith by Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery. I started reading them, responding with poems. The material is very rich—sex, religion, power, gossip, motherhood, sisterhood, jealousy. Juicy stuff. KM: You’ve managed to give each wife her own voice and an impression of her character sometimes with just a few words or a detail. An example of this are the final lines of Emma Hale Smith’s monologue: “What I know: not all eggshells are fragile. / Not all twigs snap.” This tells us so much about her and cycles back to the first line which I understand is an actual quote from Emma Hale Smith: “I did not ask for this life but accept it as my calling.” While this is a fictionalized account of Joseph Smith’s wives, how did your research come into play in terms of how you developed the voice of each wife and how you shaped the narrative of the collection? MD: I devoured the biographies and once I realized that I wanted to write a poem for each wife, that this was going to be a book-length project instead of just a few poems, I knew that I needed to get them right. They needed to be distinct, and that would be hard as they were all had similar backgrounds, lived at the same time, in the same town, shared the same faith and husband. But of course, they were all very different from each other, and I hoped to capture that. For some polygamy was something they embraced, others railed against it, and for others it was barely mentioned. The narrative was organic; I never plotted out what moments I wanted to write about. At one point I read a book about Joseph Smith’s death mask. The mask never made it into the collection, but his death was there, from a few angles. I’d read about the woman, make notes, try to hear her voice, write a draft, repeat as necessary. The first draft of the first poem I wrote for Glossolalia was Emma’s, but it took six years of rewriting her to get it right. KM: Each poem in Glossolalia takes on a different shape and form. What informed your choices about typography, line breaks, stanza breaks, etc.? MD: I believe form and content are intertwined, that they inform each other. Ultimately, it was simply a lot of rewriting, lots of playing on the page, reading aloud, and rewriting some more until it sounded and looked right. KM: In many ways, the book is more about the diverse and complicated relationships that exist between women than about the Mormon religion, but has there been any response from the Mormon community to your book and/or did you have any concerns around this? MD: There hasn’t been any direct response from the Mormon community, but I also haven’t searched it out yet, partly because I am a little scared to. I’m not Mormon, I did write about women in a community I don’t belong to, have no ties to. I am a little concerned at being called out for appropriation or being insensitive. Many of the wives have hundreds of progeny. What if there is an irate great-great-granddaughter? I shouldn’t be afraid (it’s poetry!), but part of me is nervous. I’d hate to have that kind of conflict. That said, I spoke with two ex-Mormons who came to my readings, one in Edmonton, one in Victoria. The man in Edmonton told me that I “got it right.” The woman in Victoria said that she was thankful for how respectful I treated the subject and that she’s planning on passing my book along to some in her family, many of whom are still Mormon. Those conversations buoyed me. KM: What are you working on next? MD: I’ve been working on some essays and poems that may or may not become a collection, but my big new project is a series of monologues from the points of view of self-appointed messiahs, some real, some fabricated. I’m a slow writer, but thanks to the good folks at the Centre for Studies in Religion and Society at UVic who made me this year’s Artist-in-Residence, I have space and time to create throughout this academic year. I’m very excited to see where they take me.  MARITA DACHSEL'S MOST RECENT POETRY BOOK Glossolalia, Anvil Press, 2013 Description from Publisher Glossolalia is an unflinching exploration of sisterhood, motherhood, and sexuality as told in a series of poetic monologues spoken by the thirty-four polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Marita Dachsel’s second full-length collection, the self-avowed agnostic feminist uses mid-nineteenth century Mormon America as a microcosm for the universal emotions of love, jealousy, loneliness, pride, despair, and passion. Glossolalia is an extraordinary, often funny, and deeply human examination of what it means to be a wife and a woman through the lens of religion and history. Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed