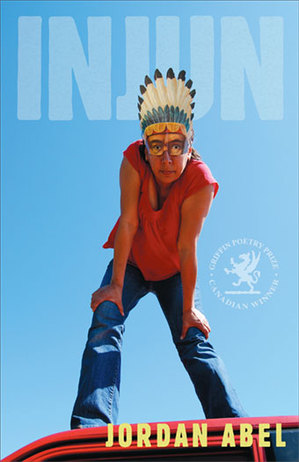

I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization. Selina Boan: So first I just wanted to say, a huge congratulations on winning the Griffin Poetry Prize! I was very moved to read part of your acceptance speech where you said the prize was “a win for all the people who fought, and continue to fight against, appropriation and against the architecture of colonialism.” I was curious to hear how you feel poetry fits into this fight? Jordan Abel: When I think about where poetry fits in, I’d have to say I am very interested in how poetry can be mobilized as a form of critique. I think you could read my poetry as being a poetics of critique but also as a poetics of decolonization. SB: What about poetry do you find valuable in helping to destabilize the architecture of colonialism? JA: It’s tough to put a finger on. It’s a number of things. One: it’s the licence to be able to use found text and manipulate it into a form of critique or reorganize it so the underlining colonial logic in those texts is revealed, but it is also about the lack of boundaries that surround poetry. Poetry is a very open, artistic genre. There are very few constraints put on poetry. Poetry can be anything and I find that really interesting about the genre. It is so fluid and flexible that it allows for a whole range of creative intervention. SB: Absolutely. Something I really appreciate in your work is the way you communicate the complexities of indigeneity using form and space on the page. Poetry as a genre can provide an alternative space to unpack the layers, the multiplicity of voices, and a variety of contexts surrounding indigeneity. JA: One of the things that comes to mind when you are talking about layers and genres is that poetry is really good at being multi-genre. Thinking even of my latest book, it is built around 91 novels. It is build out of fiction, but it is also poetry. Even my first book, The Place of Scraps, that book is built out of non-fiction as well as erasure poetry as well as photography, as well as historic fiction. Poetry really seamlessly allows for multi-genre works and I think what I like about that is you can really bring the strength of other genres out in poetry as well. SB: On that note, I read you worked with visuals in The Place of Scraps and that you had say on the interior design of the book, which is awesome. I was really intrigued if you had any say in the cover for Injun. It is an image by and of the artist, Rebecca Belmore. I was curious to know if you can talk a bit about your relationship to visual art and potentially intersections between her work and your own work. JA: Talon has been an incredible publisher. In part because they allow me to have input in the book design and printing. We looked at a number of amazing indigenous artists. We ended up with the Rebecca Belmore photo. From Talon’s perspective, they were very interested in finding a piece of indigenous art that, in their words, looks back at the reader. I think this image speaks in particular ways to the content of the writing. It’s about addressing representations and images of indigenous peoples, but it is also about where indigenous senses of identity and belonging and community intersect with those representations of indigenous peoples. Belmore’s work on the whole is fantastic but this image really speaks in interesting ways to the writing itself. SB: I would absolutely agree with that. Especially when you are thinking about representation and exploring and seeking to disrupt those representations through your work. The image seemed like a really good fit. I am going to ask a more conventional Rusty Toque question now. Do you have any first memories of writing creatively? JA: I remember when I was in elementary school having creative writing assignments. I wasn’t particularly good at them. At the time I must have been about 10 and I was playing this video game with all this amazing dialogue in it and I was like, Oh, you know what I can do? I can take all this dialogue from this video game and then write in the rest of it and I did. It’s so funny looking back on that experience because at the time I didn’t think about it, but now I recognize that was actually a conceptual project. SB: The next question I have is about the relationship between your books Uninhabited and Injun and how these collections really seem to be working in conversation. I loved the way you used separate collections to show the implicit link between derogatory representations rooted in colonization and how that feeds into the dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land. I am curious to hear about the relationship between the two books and how the various approaches and forms took shape separately? JA: That’s a really good question. After I finished writing The Place of Scraps I was interested in continuing to work with found text and I ended up on project Gutenberg where I found that corpus of 91 western novels. My first move was to copy all those western novels into a Word document and then search that Word document and figure out what all these 91 books looked like together. One of the first words that jumped out at me was the word “injun.” When I copied and pasted the 500 and some sentences that contained the word “injun” the book work for Injun all came together in this really cohesive, quick way. After I was finished I felt as though I hadn’t even scratched the surface so I started pulling out all of these other search terms, many of which ended up in the book Uninhabited. The two books became separate projects because there was so much material in those 91 western novels. Injun to me is very much about exploring race and racism and the derogatory representations of indigenous peoples in westerns. I felt very strongly that Injun leaned towards but didn’t necessarily address fully the question of land and of course those issues are connected in really meaningful ways. The dispossession of indigenous peoples from their land is in many ways connected and mobilized by issues of race and racism. They are not separate things. The two books explore two sides of this corpus. To borrow from Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman’s language, Uninhabited could be understood as a more pure conceptual book because it represents search queries about land, territory, ownership in their entirety. Although I’m not a huge fan of purity in conceptual writing, it can be useful to describe that kind of writing. There is this book called Notes on Conceptualisms written by Vanessa Place and Rob Fitterman and one of the distinctions they identify is pure and impure forms of conceptual poetry. The pure conceptual poetry is transcribing something and that is the whole work and there is no intervention whereas impure conceptual poetry would be something more like M. NourbeSe Philips Zong! where it is very clear that there is a lot of artistic intervention and the concept is derived from one legal document, but there is not a specific process as to how she carves up that document. Thinking in that language, Uninhabited is much closer to being a pure conceptual project, whereas Injun is much closer to being an impure conceptual project. In part because Injun takes on a whole lot of lyric qualities because the long poem is very sonically and lyrically inclined even though it is also a cut-up work. To me, the difference between the books is not necessarily the content but the presentation. SB: Yes, I can see that. The idea of the purely conception fits in relation to Uninhabited as you deal with ideas of search, terra nullius and these exploration narratives, whereas in Injun you are exploring more in-depth how the representation of indigenous peoples has been so manipulated, perpetuating stereotypes and misconceptions of the vanishing or imaginary Indian. It seems fitting that with your book Injun there is slightly more manipulation going on. JA: I do think that is an important part of it. Tapping into that particular kind of manipulation was very important to those settler colonial writers who, through fiction, were shaping peoples’ understandings of who indigenous peoples were for their own benefit and really destructively doing so. Doing the same thing and manipulating their words in order to comment on that issue, to me, that makes the most sense as a kind of commentary. SB: I definitely agree. Those narratives are still so pervasive. I know in my own experience that these colonial expectations of what an indigenous person looks or acts like can create a lot of misunderstanding and judgement. It’s complicated. JA: Yeah, it is really complicated. I think lots of representations of indigenous peoples, not just in westerns, have really profoundly shaped settler understanding of who indigenous peoples are to this day. I think there is very often an expectation on behalf of settler people of who counts as an indigenous person, or who counts as being indigenous, or how someone should be indigenous, or what it should look like. And there is an expectation of performativity. I think that is also tied up in this issue of what it actually means to be indigenous for indigenous peoples and what counts as indigenous lived experience and how generally we experience indigeneity. There is this whole cluster of issues. SB: I just wanted to take a moment to thank you are sharing your time and knowledge with me. I think it is important to appreciate the time, energy and labour that goes into talking about these things. So, I am curious to know, we were just talking about performativity and so I’ll switch gears a little and ask you about the performance of your poetry. I was watching an art lecture series you did for Evergreen. You spoke about being interested in the challenge of performing your poetry and you said you are most interested in those moments of the text that are difficult to perform. I was curious why performing those moments is important to you and what you hope people take away from your work. JA: Those challenging moments are really interesting to me to perform in part because they are possible to perform, but when I talk to concrete poets, or poets in visual poetry, or artists interested in visual art, there seems to be an unwillingness in trying to engage the more difficult moments. I wonder about that because I am very interested in sounds and, to me, those moments present an amazing opportunity where I can think about these visual moments in terms of sound. I can re-think the spirit of what this piece is in another medium. I also have to admit that part of it is a result of being part of a creative writing classroom. There is always a moment in a workshop when they want you to read your poem and the things that I was producing were not actually readable. I realized I should be thinking about this and finding pathways to perform this and I enjoy that challenge. Not only do I enjoy the challenge of actually trying to do it, but I actually really enjoy manipulating all those sounds and finding pathways to these ideas through sound. SB: I am so curious to know, were you already working on music and sound-based art or was this something you started investigating when you started thinking how can I perform this? JA: Yeah, the second one. I am not a trained musician, I mean I am self-taught in really the worst way. I figured it out after a bunch of trial and error. The DJ I use I don’t even use for the purpose its designed for. The program I use is one called Ableton. It is so malleable and every key is programmable. Once I realized that, I realized I could drop any sounds I want into there. For DJs it could be a drum beat or something, but for me it is voice. The technology allows me to perform in a way that speaks to the core content of my work if not that actual work on the page all the time. SB: That makes sense particularly because you work with layers and sound.. It’s awesome you were like I’m just going to try this. I’m just going to do it. That is really inspiring. JA: It’s really honestly fun for me to do and I also have to admit the more that I do it, the more I am convinced that it is important to disrupt poetry spaces. There are a range of reactions I’ve gotten to my performances. On the one hand, there are people who really are into it and they like whatever it is I am doing and they think it’s cool and interesting and, on the other side, there are people who are like What the fuck is this? This isn’t poetry! They are really angered by it. I find that range of responses really interesting. I think with the performance specifically, the thing I am hoping to accomplish is to transport my work on the page to a work in the performance setting. Because of the kind of work that I do that is a difficult manoeuvre and also can be an uncomfortable one. Likewise the subject matter that I’m talking about is not easy subject matter; it is difficult subject matter. Sometimes the performance ends up being, from what I hear, somewhat uncomfortable for people or can be, and my response to that is, when people specifically tell me that it can be uncomfortable and my question is, is art supposed to be comfortable? I wonder about the purpose of art and what artists are trying to do, and what I’m trying to do. I think that for me, honestly, what I am trying to do is to talk about these really difficult issues in indigeneity that are not only tied to these deep textured layers of the western genre, but also issues of identity and representation that are actually difficult to parse out. SB: Totally! Disruption is not comfortable. What I love about the performance space, at least from what I’ve seen of your work, is that it also creates space for exploring these ideas and offering space. I think about that a lot. How space exists in the CanLit environment and how we can work to create more space for ourselves, or for others. I’ve also been thinking a lot about the way repetition is functioning in the “Notes” section of Injun. I was wondering if you could speak a little about this section of the book? JA: The way I think through it conceptually is that these sections are gesturing towards the larger corpus. They are aimed at branching out. There are all these moments that are connected to the long poem that when you find the accompanying word in the “Notes” section what you are getting is part of the concordance line for the rest of the corpus—so that is one thing. The second thing is that it really focuses on the practice of reading contextually. So when I pull out the 500-plus sentences that have the word “injun,” I am looking at the a very similar concordance line. I am looking at all these moments that the word Injun appears and all the moments that surround them. The notes section is essentially an attempt to address what reading contextually looks like. There is the concept in linguistic called the concordance line; it is aimed at reading contextually. You read contextually for a word and read five words before it and five words after it to give some idea of how that word is deployed. Reading this way is very disruptive and alarming because it focuses in on how common certain contexts are. For example, the redskins section. All of the context around that word seems negative. Reading in this way really brings out the connotations of each word and also complicates those connotations. SB: What are you most excited or looking forward to right now, be it a book or a walk? JA: I am really looking forward to Joshua Whitehead book full-metal indigiqueer. I am not very often a poetry editor, but I am helping out with the editing for this book and I am really looking forward to working on it more and seeing the finished product. SB: And to finish. I’ve read a lot of interviews where you are asked what advice you have for emerging or new writers. It’s always a good, classic question. I am curious to know if there is anything you would have liked to tell your younger self? JA: In the past, my answer has been Know people and do stuff, which I think is true. The writing and publishing world is kind of weird that way; it does help to have personal connections and it does help to be active and visible. Somebody said something very similar to me years ago and I felt it was good advice. If I were to give another piece of advice to someone like my younger self, I think it might be something along the lines of Keep believing in the work that you do, which kind of seems cliché but one of the things I ran into when I was doing creative writing workshops is that so many people were harsh critics and ended up not actually being that helpful in my process of writing. I very often found myself just having to put aside all the advice and just doing what I wanted. Looking back, I think that was a stronger move than I ever gave it credit. It is hard to not listen to people who are telling you what to do. Looking back I am glad I didn’t listen to everybody. JORDAN ABEL |

| Description from the publisher: Award-winning Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel’s third collection, Injun, is a long poem about racism and the representation of Indigenous peoples. Composed of text found in western novels published between 1840 and 1950 – the heyday of pulp publishing and a period of unfettered colonialism in North America – Injun then uses erasure, pastiche, and a focused poetics to create a visually striking response to the western genre. Though it has been phased out of use in our “post-racial” society, the word “injun” is peppered throughout pulp western novels. Injun retraces, defaces, and effaces the use of this word as a colonial and racial marker. While the subject matter of the source text is clearly problematic, the textual explorations in Injun help to destabilize the colonial image of the “Indian” in the source novels, the western genre as a whole, and the western canon. |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed