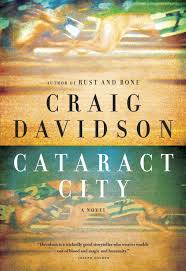

Craig Davidson Craig DavidsonPhoto by Kevin Kelly CRAIG DAVIDSON was born and grew up in St. Catharines, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. He has published three previous books of literary fiction: Rust and Bone, which was made into an Oscar-nominated feature film of the same name, The Fighter, and Sarah Court. Davidson is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, and his articles and journalism have been published in the National Post, Esquire, GQ, The Walrus, and The Washington Post, among other places. He lives in Toronto, Canada, with his partner and their child. RUSTY TALK WITH CRAIG DAVIDSON Madeline Bassnett: What is your first memory of writing creatively? Craig Davidson: Likely an assignment I did for grade 5 English; my teacher heaped it with praise, which was lovely I suppose, and encouraging, but later, when I was poor and couldn’t publish a thing, I sort of wished she’d said I sucked and ought to set my sights on a plumbing career instead. MB: You’ve received an MA in creative writing from the University of New Brunswick and an MFA from the acclaimed program at the University of Iowa. How did these different educational experiences contribute to shaping you as a writer? CD: I think they were ultimately more alike than I’d expected. Which means I likely did one degree too many. But what they did, more than anything, was give me the time to sit down, ass in chair, and get a lot of writing done. I failed a lot, got rejected a lot, failed some more, had some small successes, some more failures, then things got a little better. But of course most writer’s careers are loopy roller-coasters: there will be as many ups as downs. MB: You’re now a new dad. Has being a father changed your writing and/or your writing process? Has it changed what you’re interested in writing about? CD: I think primarily it’s solidified the idea that it is, for me, a job. I have to be up and working 5, 6, sometimes 7 days a week. It’s not glamorous. But I have to help provide for my family, as my father and mother provided for me. So it’s a big and sobering responsibility, and the only way I’ll manage to do it, as a writer, is if I’m busting my hump. Every writer I know handles themselves the same way, pretty much. There’s nothing really romantic to it, the way I’d envisioned it in grad school—although being working writer, and all that entails, is a very nice thing … for now. The wheels could spin off at any moment. But, having worked really hard, the only real way to stay in the same spot is to work just as hard. Thankfully I like working hard, and don’t have any of those preconceptions anymore about the glamour or romance of it; I understand that to be a writer, for most of us, means to write and write and write and get rejected and then maybe, if you get lucky, you catch a break. And I have responsibilities now that preclude me from being too precious about any of it—I work, I work, like my father (a banker) and my mother (a nurse) and my fiancée (a social worker) do. It’s a job. A great one, one I’m very lucky to have, but a job nonetheless. MB: Your first book, Rust and Bone (2006), a collection of short stories, was recently released as a critically acclaimed film (2012). What was it like having your stories transformed into a film? How did they turn these quite different pieces into one narrative? CD: It was fantastic. I was unbelievably fortunate. The stories were written when I was 25, 26, 27, 28—the stories off the pen of a sort of young man. They were adapted by a director in his fifties, who has a full command of his own craft. He added things to the stories that weren’t there, though he kept the rawness of them, which is likely their strongest quality. As to how they did it—movie magic! No, I think it was more a matter of finding two characters in separate stories and making their stories connect. MB: You also write horror fiction under a pen name, Patrick Lestewka. And I believe you’re more recently moonlighting as Nick Cutter. Why do you use a pen name for your genre fiction? Why two names? CD: That’s kind of my agent’s idea. He’s a good agent, I trust him, so I trust his guidance on this. Sometimes writers want a kind of separation between church and state—or in my case, a separation between gooey slime monsters and whatever literary endeavours I may decide to try down the road. I’m not really for that separation, but it is what it is. For my part, I make no real attempt to keep up the charade; it’s pretty easy to figure out that I’m all those guys! MB: Your recent book, Cataract City, is a novel about male friendship, revenge, and the power of place to shape and control our lives. It was short-listed for the 2013 Giller Prize. How did it feel to be on the short-list, and do you see this honour having any longer-term impact on your writing? CD: It was a lovely and unexpected experience. It was also tremendously lucky, as I would imagine most shortlisters would say; there’s always books that could take the place of your book, so you just have to count those lucky stars. I don’t think it’ll have an impact in terms of what I write about, no; I’ve always kind of written what I write and never expect to get any awards attention at all. I’m not really expecting to get nominated again, to be frank. It was a Halley’s Comet nomination, never again to be seen in my lifetime, and honestly I’m OK with that. MB: When I was reading Cataract City, I often thought about your gig writing horror, especially when the two boys, Owen and Duncan, wind up in the woods with their wrestling hero, Bruiser Mahoney. After Mahoney dies, the twelve-year-old boys have to survive an arduous and frightening journey back to civilization. You succeed very well in communicating the visceral horror of the situation. Do you feel that your writing of horror influences your other writing, and vice versa? CD: Absolutely. My horror book, The Troop, is about a bunch of Boy Scouts stranded on a tiny island off PEI; I wrote it in 5 weeks after finishing Cataract City, because I really enjoyed writing those boyhood sections in the novel and thought it would be good to focus on characters at that age again, except in a more overtly horrific scenario. So one side of things does impact the other, for sure. MB: As in Rust and Bone and The Fighter, Cataract City’s men are fighters, and not only in the metaphorical sense. Duncan gets involved in brutal bare-knuckle fights, and is dragged into dog-fighting matches. What draws you back to these scenes of male violence and competition? CD: Oh, good question. I think, to be honest, I’ve glutted myself on that world. The overtly male. But at the time of writing, I guess I felt that … well, listen, we all feel there are areas of human experience that we can map best. So those were mine. But I feel like I’ve mapped that area pretty damn thoroughly now. Maybe in a few years, a decade or two, I may come to some personal reckoning or something to do with my son that asks me to enter that realm again and write on it, but for now I think it’s time to hang up my boxing gloves, wrestling trunks, and so on. MB: Cataract City is also about a place: Niagara Falls. It’s a fascinating depiction of what lies behind the tourist trap around the Falls. You grew up partly in St. Catharines, just down the road. How does Niagara--and place more generally--influence you and your writing? CD: Hugely. I never really understood until it dawned that all my books were set in the area. I never considered myself a “place-based” writer, the way David Adams Richards is, for example, so many of his books set in the Miramichi. But clearly, I have that same sense of things. The results bear that out. Every book is set, at least partly, in that area. I used to think it was just because I knew those streets best—and partly, that’s exactly why I set stuff there. But I know those streets and feel comfortable about writing about them, too. And since writing a novel is often a daunting task, you need a few implicit sureties before setting out. Either the plot, or a strong character, or the place where you’re setting it. So I know that place well, and that gives me confidence—and with writing, as with many things, confidence is key. MB: What are you working on now? CD: Just being a bum, really. I’m looking after my son while my fiancée gets her Masters of Social Work. So the imagination is laying fallow right now!  CRAIG DAVIDSON’S LATEST BOOK Cataract City, published by Doubleday Canada, Random House, 2013 Read an excerpt of Cataract City in MACLEAN'S. Description from the publisher: Owen and Duncan are childhood friends who've grown up in picturesque Niagara Falls--known to them by the grittier name Cataract City. As the two know well, there's more to the bordertown than meets the eye: behind the gaudy storefronts and sidewalk vendors, past the hawkers of tourist T-shirts and cheap souvenirs live the real people who scrape together a living by toiling at the Bisk, the local cookie factory. And then there are the truly desperate, those who find themselves drawn to the borderline and a world of dog-racing, bare-knuckle fighting, and night-time smuggling. Owen and Duncan think they are different: both dream of escape, a longing made more urgent by a near-death incident in childhood that sealed their bond. But in adulthood their paths diverge, and as Duncan, the less privileged, falls deep into the town's underworld, he and Owen become reluctant adversaries at opposite ends of the law. At stake is not only survival and escape, but a lifelong friendship that can only be broken at an unthinkable price. Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed