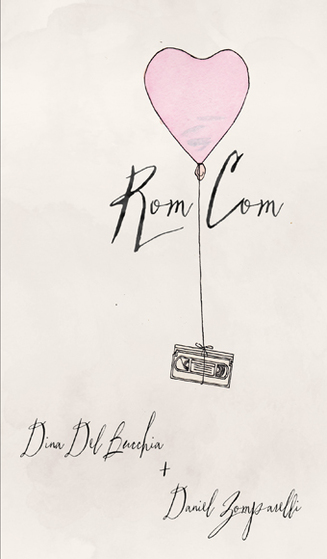

RUSTY TALK WITH DINA DEL BUCCHIA & DANIEL ZOMPARELLI Dina Del Bucchia is the author of Coping with Emotions and Otters (Talonbooks, 2013) and Blind Items (Insomniac Press, 2014). Daniel Zomparelli is the Editor-In-Chief of Poetry Is Dead magazine and author of Davie Street Translations (Talonbooks, 2012). Together, they make up the duo behind Can’t Lit, a podcast on Canadian literature. Rom Com is their collaborative poetry book from Talonbooks. Adèle Barclay: What’s the story behind Rom Com? How did a collaborative pop culture jam session between friends become a book-length project? Daniel Zomparelli: I was super sad and heartbroken, which led to a writer’s block. Since I was already a sad muppet made of sweatpants watching rom coms, I asked Dina if she would join me in a weird project to write poems about them. We didn’t really have an intention of it becoming a book. Dina Del Bucchia: Daniel asks me to do things and I say yes. AB: You’ve both published poetry collections individually before (Dina: Coping with Emotions and Otters and Blind Items; Daniel: Davie Street Translations). How did those experiences compare to writing and publishing collaboratively? How did working with each other influence your own poetic voices and inclinations? DDB: I wrote many more poems in Rom Com while I was drinking than I did while writing the other two books. Either alone or with Daniel. I am usually pretty motivated to write on my own, but this time guilt and desire to work in a timely fashion for the sake of another person surely played a part. I didn’t want Daniel to say that I was a slack-ass bitch. Also, having another person was so great for support and ideas and generally having a fun time while writing. DZ: LOL, imagine if I ever called you a “slack-ass bitch.” DDB: Because of the back-and-forth nature of the initial stages of writing there were times when we were so closely mimicking each other that we couldn’t figure out which of us had written certain poems. DZ: There was a lot of weird cross-over in voice. I was uncomfortable about that at first, but then it also made sense for the book, and we’ve always kind of had a similar style so it ended up working. Plus I should be so lucky to ever write in Dina’s poetic voice. Writing alone is scary. It’s just you bouncing ideas off a wall. I’m much happier to bounce ideas back and forth with Dina because she amplifies ideas. Both figuratively and literally. AB: Writing can often feel pretty isolating—I mean logistically the process of writing requires time spent alone. But this book and many of your other projects, such as the Ask Dina and Daniel advice column and your CantLit podcast, are predicated on collaboration and reaching out to various social, literary, and artistic circles. Why is making literature communal and collaborative important to you? DDB: Without these communities we do feel much more alone and sometimes defeated. And because there are already enough dicks out there in the world trying to make writers and artists and people feel like they’re not worthwhile and that neither is their work. When you find people you get along with and can work with, well, that is really special. That is the mushy part. But it’s true. I think it can be hard to feel like you’re accepted as a writer and to feel legitimate because there are barriers and gatekeepers. I hope we’re not those things. If people feel like I’m being mean to them it should be because they’re assholes and that they deserve it, not because I’m in a position of power, which, I mean, clearly I’m not. I’m not saying I’m perfect either. Far from it. I make a shit tonne of mistakes in this area all the time and hope to be less crappy the next time. DZ: I don’t have much to add that Dina hasn’t already covered. I will just say that writing is lonely, but I’m not convinced it has to be. Dina and I are just doing as many projects as possible to convince ourselves that writing doesn’t have to be lonely, and we’re seeing what sticks. AB: The poems of Rom Com are almost parodies, but ultimately they do something unique by combining reverence and irreverence. Were you trying to strike a balance between criticism and appreciation? What can you do in a poem that you can’t in a film review? DDB: With anything in life, even the person you love most, there are parts that you don’t love as much. There are stinky parts. We assume that love means only reverence, but that’s not the case. As a genre you love rom coms in spite of their inherent flaws. And also some rom coms are great and others are not so great. Some things you love even though you know they’re not considered “quality” by film critics because they provide some comfort or joy or even the feeling of superiority, like,”Shit that movie is bad but I want to keep watching to make fun of that, but also maybe I have a crush on that actor in it.” Shit is complicated. DZ: Critiquing something always makes me appreciate it more. I’ve had people assume I hate everything because I critique everything, which is the opposite. If I truly love something, I like to pick it apart and see how it works and yes I will find things I don’t like, but that lets me understand it more. I can critique Santa Baby and Santa Baby 2 starring Jenny McCarthy for the main actor’s politics and the obviously terrible plotline, but I can still enjoy the movies considering these critiques. That’s probably a bad example, but I just wanted you to know that movie and its sequel exists. DDB: One important thing you can do in a poem and not in a review is swear. And use the word dick a lot. Poems, even formal poetry give you language freedom. And no one is ever going to read a poem and then decide that they will or won’t see a movie. But they might still fight with you about your opinion on it. People love to fight about poems. DZ: I like that poems give a safer space because no one reads them. I know that sounds like a joke, but with a limited audience you feel less pressure. I’m more worried about the backlash of a harsh tweet than a critical poem. AB: The collection is hilarious. And yet the poems are often deeply sad and perturbing. You pick at the troubling currents of mainstream culture that the genre tends to gloss over—homophobia, transphobia, slut shaming, racism, casual misogyny, messed up power dynamics. For example, in “A Series of Romantic Comedies that Could Never Be Made” you deftly point out the dearth of main stage queer storylines in Hollywood. The twin poems “Adam Sandler: A Love Story” and “What’s Not to Love, Adam Sandler” build Sandler up and then critique his racism and transphobia. What is it about poetry that makes space to address these issues? DZ: I think I summed this up in the previous question, but it’s very much a limited readership that makes me feel safe to do this. That might be a false sense of safety. Also that poems get to hide around vague concepts and ambiguity. There is definitely a safety in someone reading it and not “getting it.” DDB: I agree with Daniel. The freedom of low readership. I also think the great thing about a poetry collection is that it can encompass so many things at once and still feel cohesive, especially when writing about a particular topic as we did in Rom Com. Rom coms are all of those things you mention: hilarious, sad, disturbing, sexist, homophobic, racist, transphobic. With a collection you can focus on aspects of one element in one poem, and then respond with another and because of the unified concept everything comes together to form a full reflection. AB: In Rom Com, there are list poems, found poems, and poems made from mining locations, tropes, plotlines, and types of humour in romantic comedies. To what extent did riffing off film tropes affect how you approached poetic forms? What kinds of poetic tropes worked best for this book? Did the prompts take you to any new places poetically or lead you to any styles and voices you hadn’t tried before? DZ: Yes. Experimentation can lead to new things. I get excited with every new poetry project to try things I’ve never done before. I do a lot of visual poetry experimenting and that’s the toughest for me because I’m not a very visual person. Lots of those go in the garbage, but I’m happy with the few I created for the book. Dina: I love Daniel’s visual poems so much. I’m really happy they’re in the book and with how they are these beautiful, skewed section breaks. Like Daniel I get excited about trying new things and not relying on all my old tricks. We did a lot of riffing and a lot of trying to mirror film tropes and some yielded cool things that took us in interesting directions and others were terrible. Using the screenplay structure to address rom com sex scenes was an idea I was so unsure of, but it ended up staying in the book. It’s weird but it also opened up a way addressing a common rom com element through an unfamiliar structure. AB: In addition to contemporary romantic comedies, you delve into the history of the genre. The book travels back to the 1980s with Moonstruck and When Harry Met Sally and the 1950s with Some Like It Hot. You shine a light on the 1930s—the golden age of screwball comedies. In “It Happened One Night,” one of the first poems, you point out how that film won an academy award and “it wouldn’t happen like that now, / get serious.” How has the romantic comedy changed over the years? How have our attitudes towards it changed? DDB: In some ways rom coms haven’t changed at all. They are still very heteronormative films with white protagonists searching for love. They’re films about those people finding each other, fighting and ending in two people getting together and seemingly solving all their problems merely by that fact alone: being together. I think rom coms are less popular than they used to be. And also there is a much bigger divide in who the audience is. Straight men need to be convinced that they aren’t “women’s stories.” Which is fucking disgusting. Men’s stories are for everyone, but women’s stories, well, they aren’t to be enjoyed by straight men, especially if the main protagonist is a woman. Girls are encouraged to watch superhero movies, which is great, but boys aren’t encouraged to watch Bridesmaids. When obviously they should be. DZ: Everything Dina has said should have 100 emojis and fire emojis all around. AB: I’m curious about how you see these poems relating to love poetry. Like love poetry, the poems often address the second person, but unlike love poetry the “you” is rarely the beloved and is, rather, addressing a celebrity or character from a Rom Com. Who does this collection of poetry address? How do these poems diverge from or converge with love poetry? DZ: This collection is addressed to all of my past, present and future lovers. DDB: I think our concept of love poetry can be as narrow as our concept of rom coms. But it shouldn’t be and so many of these poems are love poems. Writing about love should address how it’s messy and sad and funny and gorgeous and confusing. AB: Do you think you can calculate poetic compatibility like an OKCupid match score? Or is it all alchemy? DDB: If I thought that more than 10 people would use a Tinder poetry app I would totally find a smarter person than me to make one. DZ: I can’t imagine the Tinder poetry app would be much different than the regular app. Although I’d like to see what a poetry dick pic would look like. Or, I imagine that whether you swipe left or right on their photo, you still have to listen to them talk about their next poetry project for 30 mins. DDB: I bet a poetry dick pick would just be an author photo. DZ: To honestly answer your question: poetic compatibility doesn’t mean friendship compatibility, so I don’t think it would work. There’s a lot of poetry I love and feel that it’s compatible with mine, and some of the authors are terrible people. If there was an IRL block function on this Tinder poetry app, then I would be all in. DINA DEL BUCCHIA & DANIEL ZOMPARELLI'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed