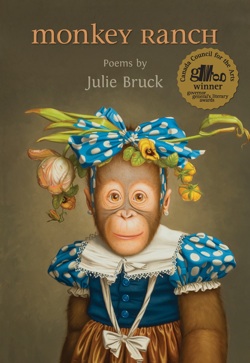

Julie Bruck Julie BruckPhoto by Kara Schleunes JULIE BRUCK is the author of three collections of poems from Brick Books: Monkey Ranch (2012), The End of Travel (1999), and The Woman Downstairs (1993). La Singerie, William S. Messier’s French translation of Monkey Ranch, was published in 2013, and is available from Les Editions Triptyque. Her awards and fellowships include, Canada’s 2012 Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry, The A.M. Klein Award for Poetry, two Pushcart Prize nominations, Gold Canadian National Magazine Awards (twice), a Sustainable Arts Foundation Promise Award, as well as grants from The Canada Council for the Arts, and a Catherine Boettcher Fellowship from The MacDowell Colony. She lives in San Francisco’s foggy Inner Sunset district with her husband, the writer Lewis Buzbee, their daughter Maddy, and two enormous geriatric goldfish. RUSTY TALK WITH JULIE BRUCK Tom Cull: What is your earliest memory of writing creatively? Julie Bruck: When I was quite little I wrote a rhymed poem that began, "Nonsense is so many things,/ bats with hats and cats with wings." My mother made a huge fuss over it, but I wasn't as impressed. I never really felt engaged by writing as a kid. I preferred drawing, or being outside--preferably with live, rather than imaginary animals. TC: As a child, did you read poetry? Was poetry a part of your childhood? JB: Poetry was read aloud in our home, and valued. My mother wrote poems and studied with Irving Layton, and went on to publish her first chapbook in her mid-80's. My father liked to quote Ogden Nash and lyrics from Gilbert & Sullivan. There was a lot of word-play in the house. My two older brothers tortured me with names I didn't understand, like "perpetrator of arm-chair methods" or "petit bourgeois scum." Eventually, the dictionary became a survival tool. TC: How did you become a writer? JB: I wasn't drawn to writing until my early 20's. I was studying photography and art history and took a fiction workshop at Concordia University as an elective. My stories were awful, but that class woke me to the kinships between poetry and photography, especially how both were a matter of framing, and how crucial the placement of that frame could be. That fit with my way of seeing the world. I was really adrift at that time in my life, and I think that process offered an illusion of order. It also made my work too drum-tight and over-determined, but there would be time to work on that later. TC: You were born and raised in Montreal but now live in San Francisco. How has this transplant affected your poetry? JB: My relationship to home was always hyphenated, especially as an Anglo in Quebec, so being a Canadian in the U.S. felt oddly familiar. I think becoming a mother at 41 was the bigger shift, and certainly one that had an effect on my work. As a parent, it's harder to draw lines between what's personal and what transpires in the larger world. The traffic between those two realities figure in my writing. TC: Your website describes you as both “poet and teacher.” Can you talk about the relationship between writing poetry and teaching poetry? JB: Much of my teaching focuses on generating new work, and I emphasize the importance of surprise in the writing process, as well as during revision. The bold examples of my students help keep me honest. They are almost always receptive to trying new strategies and approaches. They remind me to practice what I preach, and I'm grateful for it. TC: Can you describe your writing process? How does revision figure into the process? JB: While most first drafts come quickly and freely, I am glacially slow from that point on, and can spend years on a poem before it's either ready to leave the house, or be consigned to a dusty folder. Revision is crucial and I print every draft. I am not, alas, good for the forests. So often though, the most creative moments take place during re-writing, even years after the rush of a first draft. Sometimes, it takes that long just to step out of the poem's way. Those moments are worth waiting for. They're exhilarating. TC: Do you have any advice for newer poets who struggle with evaluating feedback from their peers? When should a poet bend to critique and when should a poet stick to his or her guns? JB: I think how you respond to input depends on temperament and experience, among other things, so it's hard to give boiler-plate advice. On the other hand, it can be very useful to soak up feedback from your mentors and peers (and from your reading) when you're "new" at poetry. Sure, the poem belongs to you, and no-one can "steal your voice" and you can always revert to your original version. Ultimately, though, the poem must also belong to the reader, and your colleagues can be great indicators of how and what that poem is communicating. Good readers can also keep you open to what the poem might be reaching for, even if that differs from the poem you set out to write. This can teach you to read your own words on the page, which might already have better plans for themselves.. TC: You have spoken elsewhere of your poetry being characterized as “accessible.” Is accessibility important to you as an artist? Is it something you strive for in your writing or is it just the way you write? JB: Sometimes I regret using that word. Accessibility gets a bad rap, as if it suggests poems which suit the reading habits of a well-meaning duck. What I'm after in my work, and what I look for when I read, is clarity. I find that the clearer a thing is, the more mystery it possesses. I do not equate confusion with mystery. TC: Confinement and threshold seem to be recurring themes in Monkey Ranch. Whether it be a Howler Monkey in a zoo cage, a race-horse (“a gleaming ton of coiled muscle”) standing ready at the gates, a shark in a sling being released into the ocean, or even the “liquefied sunlight” trapped between two doors of a vestibule, your poems seem to characterize people, animals, and things as either caught between and/or poised to break out. Do thresholds hold a particular significance in your poetry? Do you see your poetry as negotiating a relationship between confinement and freedom? JB: What a terrific question! Someone else recently characterized my work as "the poetry of aftermath", but thresholds and the negotiations between confinement and freedom certainly resonate. There's a line in my first book, The Woman Downstairs, in which the speaker describes herself and her entourage as "always on the threshold of some promised definition." I think part of this interest in being on the verge has to do with an adolescent quality that I keep expecting to outgrow--the idea that we're all in a state of perpetual emergence, and that on the other side of that process, everything will be clear. Ha! I think these cusps also reflect the tension between the (apparent) simplicity of innocence and the endless complications of knowledge. It's a tension that's so beautifully dramatized in Elizabeth Bishop's poetry, and your question helps me explain the abiding affection I have for her work. It's also a tension that's inherent in raising children, and in being with animals, since both are so vulnerable to the caprices of human adults. Finally, thresholds always signal some kind of change—that uneasy, and most interesting part of human affairs. Adrienne Rich said, "The moment of change is the only poem." That's a quote I carry in my head, and if I was 30 years younger, it might be a tattoo. TC: Monkey Ranch is both the title of your book, and the title of one of the book’s more disquieting poems. The “monkey farm” in this poem is one of the many cages or prisons found in this collection. But the title also seems to be a play on “Monkey-Wrench,” a tool that derives its name from the nautical meaning of “monkey” as any provisional tool designed to suit an immediate purpose. To this connotation must be added “monkey” as meaning “mimic,” “mock” and “play around.” All of these meanings seem alive in this collection—often simultaneously. Can you say something about the choice of the title and how it works as a sign that marks the entrance to your poetry zoo? JB: Monkey Ranch was my choice for the book's title, though my editor was resistant. She didn't feel that the poem was representative of the collection as a whole. She also thought the title, especially in concert with the crazy cover image, suggested a lighter book than I'd written. I could see her point. As a title poem, "Monkey Ranch" is more surreal than most of the other pieces, but I felt quite certain that it knit together various themes and impulses that ran through the book. Thematically, those included the caging you point to, creatures, family life, and the ways we often recall and talk about painful memories, but only selectively. As far as the word-play in the book title, you've nailed it! This was a tricky book to order and shape because of the variations in voice and tone from poem to poem. The potential wordplay in the title was intended to pick up a playful thread that also runs through the collection. My hope was that giving a slightly stretchy title to what is, at heart, one of the darkest pieces, would speak to what the book as a whole presents. I think you said it best: that all these meanings inhabit our monkey lives, "often simultaneously." Thanks! That's exactly what I was after. TC: What are you currently working on? JB: I'm writing new poems and just letting the drafts stack up. It will likely take another year before I start rearranging them into anything remotely bookish.  JULIE BRUCK'S LATEST BOOK Monkey Ranch, Brick Books, 2012 Description from the publisher: Winner of the 2012 Governor General’s Award for Poetry Globe 100 Book for 2012 Shortlisted for Pat Lowther Memorial Award and CAA Award for Poetry 2013 Comic and sober by turns, these poems ask us what is sufficient, what will suffice? … a mandrill, a middle-aged woman, a shattered Baghdad neighbourhood, a long marriage, even a spoon, grapple with this unanswerable conundrum—sometimes with rage, or plain persistence, sometimes with the furious joy of a dog who gets to ride with his head through a truck’s passenger window. Julie Bruck’s third book of poetry is a brilliant and unusual blend of pathos and play, of deep seriousness and wildly veering humour. Though Bruck “does not stammer when it’s time to speak up,” and “will not blink when it’s time to stare directly at the uncomfortable,” as Cornelius Eady says in his blurb for the book, “in Monkey Ranch she celebrates more than she sighs, and she smartly avoids the shallow trap of mere indignation by infusing her lines with bright, nimble turns, the small, yet indelible detail. Bruck sees everything we do; she just seems to see it wiser. Her poems sing and roil with everything complicated and joyous we human monkeys are.” EXCERPT FROM MONKEY RANCH

MONKEY RANCH Our monkeys were striped green and yellow, except for the red and white ones. Outside the house, a screaming kaleidoscope of stripes chased stripes, until they settled in the branches at dusk, to pick each other's nits. Father tired of monkey farming, took a job in town. We starved our monkeys. Day by day, they slowed, and when I picture them now, or dream of how it was, they stagger in the black and white of old newsreels. It took them a whole year to die off while we watched. In those days, children did as they were told, and Mother always favored chinchillas. But they used to wear such cute little monkey hats-- red, white, yellow, and green. THE CHANGE So, I’ve done what my body was made for. My eight-year-old is all legs, careening down the basketball court, and I do acknowledge the pulls and pushes of tides, moons, of love and such, even if I stop short at crystals and meet-the-plankton music. My husband hums in the house, my daughter sings while she plays. I’m hunched at the kitchen table, jaw clenched, staring down a blank grocery list when that stringy mouse, the one who holds keys to this place, scrabbles across the awful linoleum for the first time today and my shriek is so sudden and muscular and primal I know I’ve pulled something in my neck. If this new Tin Cat™ does its job, I swear I’ll carry the jumpy, humane contraption straight to the park in my bathrobe, calmly raise the metal lid and let the mouse go with a kind, steady hand. I’ll be better than I am, pretend to love this creature I'd rather drown. What does it mean to love the life we've been given? Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed