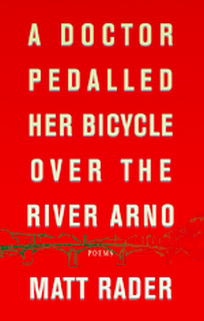

RUSTY TALK WITH MATT RADER Matt Rader Matt RaderPhoto by Ron Pogue Matt Rader is the author of three collections of poetry, Miraculous Hours, Living Things, and most recently, A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno. His poems have recently appeared in publications in the United States, Romania, the Czech Republic and Canada. He lives on Vancouver Island. Kerrie McNair: How did you first get into writing? Matt Rader: That’s one of those questions of history I’m always tempted to rewrite. I probably have several times. I recall writing in school as a kid. And I recall writing poems with my mum when I was eight or nine. Then I wrote poems all through high school. I took writing classes at the University of Victoria from age 18-21. But I didn’t start seriously until the fall after I graduated from my undergrad. That fall I wrote a poem called “Exodus.” Later that poem became the first poem I published professionally in sub-Terrain magazine. KM: What poets or writers did you read you when you first started out? Who are you reading now? MR: In those earlier years after my time at UVic, I read Ted Hughes exhaustively. Then I read Seamus Heaney who remains a major influence. Michael Longley was my primary influence for more than half a decade. In the last few years Larry Levis has been hugely important, and most recently I have fallen in love with Mary Ruefle’s poems. Heaney, Longley, Levis, and Ruefle are all currently represented in the Jenga of books on my bedside table. I could also tell this story with Homer, Keats, Hardy, Yeats and Eliot. Or Bishop, Plath, Lowell, Gilbert, and Larkin. Not to mention Babstock, Solie, O’Meara, Thornton, and Bachinsky. The problem with any list like this is that I can’t help but make egregious and unforgivable omissions. KM: You used to run a literary micro-press out of Vancouver for writers who were marginalized for a variety of reasons including age, content matter, sexuality and ethnicity. Can you describe how you got into literary/cultural activism and how it informs your writing? Are you working on any community projects at the moment? MR: I was lucky enough to meet a set of young artists and writers, largely centred in Vancouver in the early aughts, who had a desire to share their work with each other. Many of us had grown up in the DIY music and zine culture. Several of us were involved in various queer communities. We were culture makers and pursued that right into our publishing deals and writers festival invitations. I’ve been involved in several projects lately and there are few more in the works. A year ago I collaborated with my friend Grant Shilling to put on a community storytelling event. We live in a small mountain village on Vancouver Island. The foothills here have been ravaged over the last century and a quarter, first by coal mining and then later by logging. Currently the hills around our village are used both industrially for logging and recreationally as a major mountain biking destination. The event was called Bronco’s Perseverance: Changing Gears in Cumberland. Bronco’s Perseverance is the name of one of the main trails along Perseverance Creek. The trail is named after the long time Cumberland mayor, Bronco Moncrief. Our tagline was “Beer and bullshit.” It was amazing. This past summer I collaborated with a local designer, Sarah Kerr, to create large poster-sized newspapers modeled on papers from the 1913 that we researched in the Cumberland Archives. There were six pages and they told the story of two young girls during the height of the Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike that was 100 years ago this summer. We put the posters up around town. I wouldn’t say that my cultural activism informs my writing exactly, but I do think my writing is informed by the same impulses as my cultural activism. I can be didactic about it and try to make a case for aesthetic and moral value, for form and identity, for art as experience, but in the end, those impulses are as known and as mysterious to me as to anyone else. KM: You’ve been involved in curating several reading series such as the Robson Reading Series. Do you have any advice for new poets or writers on reading their work for an audience? MR: Read as slowly as you possibly can, then read a little bit slower. Always read less. I believe Mark Twain has a set of rules. Google Mark Twain’s rules. KM: Can you describe the writing process for your most recent collections of poems, A Doctor Pedaled Her Bicycle over the River Arno, which your publisher describes as unraveling “our layered identities to explore the lyrical fabric of humanity”? Over what length of time were the poems written? Was there a particular catalyst for this project? MR: The earliest poems in A Doctor were composed alongside the bulk of my previous collection Living Things and I was in the midst of composing the core poems in A Doctor when Living Things came out. All told, it probably took about three years to write. I was pursuing several things in that book. One was a reintegration of narrative into the poems, something that I felt I’d written out of my poetry in Living Things. Secondly, I was exploring cultural history in a way that I had explored ecocultures in Living Things. I was particularly looking at my family history on one hand, and the colonial and post-colonial history of coastal British Columbia on the other hand. It wasn’t really an either/or. These histories were more braided than that description suggests. Thirdly, I had been thinking since Living Things about poetic form and tradition and in A Doctor that became expressed as custom and customs. I was intrigued by the idea that custom and customs (or costumes as Elizabeth Bishop would have it!) can be both the guarantor of civilization and a purveyor of horrific violence. KM: Many of the poems such as “I Acknowledge: and “History” in A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle over the River Arno detail the lasting presence of history in contemporary life. How did the past motivate your desire to define the present when it came to writing these poems? MR: John Dewey says “art celebrates with peculiar intensity the moments in which the past reënforces the present and in which the future is a quickening of what now is.” I really like how he says, “what now is” instead of “what is now.” I know that I should be more generous and explain what I think this means, but I don’t want to. I tend to see everything relationally, which is to say with a kind of historicity. KM: Conversely, poems like “Natural Lives” and “Homeowners Manual” address sentiments of devotion. Was it a conscious decision to, at some point, stop looking back? MR: No. I never did stop looking back. Though I don’t think of the past as being “back there.” Looking at history is looking in the mirror. Looking in the mirror is looking at history. KM: What is your funniest or favourite literary moment, if you have one? MR: When I was a small boy Dennis Lee came to my small island town and gave a reading for children. I remember the bookstore as having creaky old wooden planks for a floor. Everything seemed very dark. He picked me out of the crowd and sat me on his knee and began to recite a poem. To which I promptly ran away crying. Then, nearly thirty years later, after the launch of my last book in Toronto, I walked out the party and standing in the street at the bottom of the stairs was Dennis Lee. He was holding my book! I introduced myself and we said kind things to each other and then I told him the story I’ve just related here and he said … well, I can’t tell you what he said, not in print. But if I’m ever in your town you can buy me a beer and I’ll tell you the rest … KM: What are you working on now? MR: I have a collection of short stories that’s meant to come out next fall. I’m also working on a new book of poems with a kind of deep hermetic code. They’re largely elegiac. I’m also about to embark on a filmmaking project with a young filmmaker, called Jim Vanderhorst. I have a chapbook of poems coming out with Baseline Press at some point in 2014. Enjoy an excerpt from Matt Rader's forthcoming chapbook from Baseline Press: UNSPEAKABLE ACTS IN CARS It’s the first day of summer and we’re so happy To see the sun and the satchel of colours it schleps All those dark kilometres. The sky is so blue And the sea is blue and the small islands in the sea Are blue also. How our sun must love blue. We have beachgrass and bull kelp and lion’s mane And we love them all because we love the sea Which is cold and buoyant. Friends now of seasalt And knotweed, the mountains know all about us And who we are when we are most ourselves. But their blue haughty distances are no help. We are who we are with mock orange and wisteria. We’ve nothing to bitch about. The high cirrus Can’t touch us. We been alive just long enough. originally published in The Fiddlehead 253 DOVE CREEK HALL (FORMERLY SWEDES' HALL) The children play their fiddles so slowly I am sad For the old wooden hall among the cow patties. Who cut the rhodo blooms and set them on the piano? They bow tiredly through every tune. Even the cows Have wandered away from the music to the far side Of the pasture. All the Swedes who built this hall Are dead now and the women they married are dead And the pastor who married them and their friends. But the children do not know this or just how sad Beauty is on the last day of spring with instruments And young players making music beneath the rafters. They play along with mistakes and embarrassment. Tell me, who hung the hand-stitched stars on the wall? Who hung the evening light from the windows? originally published in Arc 67  MATT RADER'S MOST RECENT BOOK OF POETRY A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno House of Anansi Press, 2011 Description from publisher: A Doctor Pedalled Her Bicycle Over the River Arno carries within it all the technique, vision, imaginative labour, and razor-sharp precision of Matt Rader’s first two collections, Living Things and Miraculous Hours. But it also ascends to a new and luminous, demanding, particularized realm of the human. Wildflowers and weeds, newspaper archives and illness, hostels and hostiles, parenting and the shadowy history of grandparents, war and Renaissance paintings: Matt Rader’s unassuming, deeply spirited, and expansive poems show us again how contemporary lyric can go such a long way toward revealing our true homes to us at the moment we find ourselves most nakedly un-housed. Rader seeks out limits, borders, and frontiers—those mapped for us by authority, and the concomitant, interior shadowlines we ourselves draw—in order to test their validity. Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed