RUSTY TALK WITH MICHAEL PRIOR

"I think distraction is in a way essential to my poetics." John Nyman: I find many of the poems in Model Disciple especially dream-like: your sentences jump between times, images, and ideas, and the connecting threads are often buried at least one layer below the surface. Do you think the comparison between poetry and dreaming is accurate? Michael Prior: It’s interesting, because we talk about how relating a dream to someone is one of the most boring things in the world: no one wants to hear someone else’s dream. But in a way I feel like poems often are our own dreams, though we’ve done something that’s made them palatable for an audience. Perhaps what you’re picking up on is that I often embed the narrative in different ways. For the most part, I’m not interested in writing strictly narrative poetry, and part of that means subordinating any kind of narrative sense to an associative sense. JN: Regarding that “associative sense”: It also struck me that many of your poems are about incredibly personal and in some ways very urgent subjects, but at the same time you seem totally willing to deviate from this urgency—for example, by refocusing attention on a beautiful image or even just a poetic sound pattern. I think of these almost as ornate aspects of the poems. What draws you to the ornate, or what leads you to focus attention on these kinds of images? MP: I would hope that most of these images or lines are reframing the poem in some way. Because these poems are often about deeply personal and often deeply political things, historical things, with a perspective on trauma, and loss, and the deprivation of citizenship. If I were just to write exactly what I mean, to follow a more argumentative or direct logic—though there’s lots of great poetry doing that—it wouldn’t be true to my experience, which is one of confusion and constant distraction. I think distraction is in a way essential to my poetics. Maybe it comes back to the dream thing: dreams are full of distractions and the inability to get where you’re actually going. I’ve never had a dream where I’ve accomplished anything I wanted to accomplish in that dream. Most of my poems, if they do have ornate moments—I don’t know if that’s exactly the word I’d use—or if they do have consciously poetic moments, it’s because their inclusion somehow rings more true to me. I don’t think my experience of the world has been so linear, so teleological, so politically straightforward. It’s often the same with the poets I’m interested in, too. If you look at the work of Bishop, Lowell, a lot of mid-century people like that, or even later poets like Merrill and Gunn, the ornate can be very political. The ornate can say something by re-framing an idea, or by subverting a set of semantic expectations through the reflexivity of form. I hope that these moments you’re talking about were surprising; if they weren’t, then perhaps I didn’t accomplish what I was aiming for. JN: Surprise is definitely a big part of it. I think what’s often happening when I read your poems is that there’s a strong narrative I can start to pick up on, but then I’m surprised by how it comes through in these images. They can seem unrelated at first, but they quickly become a striking and integral part of the experience. MP: I’m glad that you called it experience, because that’s very much what I’m thinking about with the poem. I do think of the poem as in some sense an object, but I’m really interested in the poem as experience, and that’s something I was very conscious of when writing the book. For me, poetic experience is situated in those tough to define intersections between a poem’s formal elements and whatever impulses may exist in the poem toward narrative order or the sense of sense-making—so you have to do something interesting there. That’s why I made the decision to write the last poem in blank verse, and that’s why a lot of these poems move in and out of different metres: I think it does something inherent to our experience of the poem. JN: A very blunt question: Can poetry be an experience of the self, or a kind of self-discovery? MP: Maybe. I think it can, certainly. But I am wary of poetry as self-discovery. Oftentimes I think I’ve found out something and I start writing a poem, but by the end, I realize I’m actually more confused than ever. Yeats said that we make rhetoric out of our quarrel with others, but we make poetry out of our quarrel with ourselves—and while I don’t think the distinction is always that set, for me at least, that formula seems accurate. JN: On that theme: I had a question about the final poem in Model Disciple, “Tashme,” a long poem that narrates you and your grandfather’s trip to some of the sites where thousands of Japanese-Canadians (including your maternal grandparents) were forcibly interned during World War II. There are a few moments within the poem’s narrative where you reflect on your reasons for writing the poem—or, more precisely, where you’re trying to figure out what those reasons are. Why did you set out to write “Tashme,” and how did these reasons change over the course of writing, editing, publishing, etc.? MP: Oh my! I think there were a lot of changes on all the levels you mentioned. I set out to write the poem because that event, and particularly that camp, has been at the centre of my family mythology for as long as I can remember. When I was in grade five or six I interviewed my grandfather about it for a class project, and even at that age I realized how thoroughly the reverberations of that event had shaped his experience, my grandmother’s experience, my mother’s experience even, and were in some ways shaping my own. Tashme became something I felt magnetically drawn towards. So, going back to your question about self-discovery, perhaps I started it to better understand myself and my own thoughts, but as is usually the case, I’m not sure it lead to a better understanding, only a quarrel with myself on the page. After my undergrad, I started planning for a road trip, wherein I would visit most of the former internment sites in British Columbia, including Tashme; I would invite my grandparents to go with me and I would write about it. It didn’t take long for me to begin wondering whether such a trip might be more problematic than I’d originally thought: What would it mean to my family if I wrote this poem and then published it? What would it mean to my grandparents, specifically? Was going on this trip truly important for my understanding of my family? After all, I was going into this experience with the express purpose of writing about it. But I still felt this pull to go, and although my grandmother wasn’t interested, my grandfather wanted to accompany me. It became apparent that his main reason for doing so was really just to spend time with me; he was mostly interested in watching the Jays games, catching up with me, and explaining our trip to people in the towns we passed through. I think a lot of people of his generation aren’t interested in going back, understandably. He really enjoyed telling everyone we met about the trip, but when we were actually at the sites, alone, he was very quiet. I felt terrible about that; I feel terrible about that. We still talk about the trip often, and he has a very positive attitude towards it—more so than I do, even. But I still feel very guilty about certain parts of going on that trip. I don’t know. There are a lot of questions I still can’t answer. Because of the poem’s length and preoccupations, editing it was a difficult process. When I started writing “Tashme,” it kept coming out as too poetic, too flowery. I also wasn’t in the poem at all; I would do everything I could to keep myself out of it—and I still don’t think I’m in the poem a lot. I try to let my grandfather speak and let other people speak, and to be there with him, because I felt that was one of the ways I could write the poem and make it respectful of his experience. My editor and I went through so many drafts, from about 25 pages all the way down to 18. At one point, when we were struggling my editor gave me some good advice; he said, “Write this as if you were a journalist,” and that’s how I approached the piece. But doing so, of course, was also another way of reshaping the narrative because of all the stuff we had to cut. I think at the end of the day, one of the biggest realizations I came to with the poem was that it had to be rooted in my love for my grandfather, in my love for my grandparents, and my love for my family. Ultimately, every decision I made about the poem had to be based on love, appreciation, and respect. And so there were moments that I couldn’t keep, because it would have been too painful for my grandfather, or my grandmother, or my mother. And if that diminishes the poem in certain ways, I’m willing to live with that. JN: I don’t know if this resonates with you, but one of the ways I understood Model Disciple was to see the shorter poems (which make up the bulk of the collection) as the book’s dream discourse, and “Tashme” as its waking discourse. From the shorter poems to “Tashme” the style very much changes, the perspective changes, and the structure of the events changes. MP: I think in some ways that’s very true. And I think, maybe, there’s a gradual waking throughout the book, if we’re putting it in those terms, as the poems grow more and more direct in their logic, their biographical content. Was that your experience? JN: Yes. I don’t know about direct, but there is a definite building of a concept of the self, or at least a placement within a larger reality from the beginning of the book towards the end. MP: Right. And I think that parallels the movement of the poems as they become more directly engaged with the internment, rather than using a series of masks: the mask begins to fall off, and it becomes more of just me speaking about that family mythos. I like to think of the poem to my grandmother, “Haruko,” [which appears immediately before “Tashme”] as a poem that speaks its mind. JN: I like the phrase you just used: “the mask begins to fall off.” It reminds me of some themes from one of the first poems in the book, “Ventriloquism for Dummies”: Drop me, toss me, and I lie limp: a tidal tryst of bleached branches, a good joke gone bad, or a line soured by time. Got wood? It’s all I’ve got. These lines suggest a speaker who feels like they’re in some way derivative, like they’re just copying models—of course the title of the book is Model Disciple. How close was this to your position when you wrote the poem, or any of the other poems in the book? MP: I think that’s a very astute observation, that there is some kind of tension between inheritance, identity, and whether any sort of originality is possible. I mean, God, I don’t want to mention Harold Bloom-- JN: (laughing) I already did in my original version of the question! MP: Well, I think there is a conversation happening, and sometimes when I was writing the book I felt that my voice wasn’t quite loud enough. How do I get my voice to be louder? How do I become more articulate, in order to speak to all these other voices? You need a conversation rather than anxiety, a conversation rather than influence, maybe. To me, the book is trying to engage with a large number of other texts and figures. There are poems in there that directly play off other poems, canonical poems. A large portion of the book has to do with how I situate my own confused subject position amongst the English canon, capital-E, and how I situate myself within Japanese-Canadianness, and also halfness. I’m reticent to say much about Japanese-Canadianness because it’s such a diverse range of experiences, and also because I grew up not really knowing many other Japanese-Canadian people apart from my immediate family until I reached university. But I think lots of the poems really struggle with—well, perhaps this is something all poems deal with in some way—they struggle with the idea of being spoken through or speaking for yourself, that kind of tension. “Ventriloquism for Dummies,” for example, is based on a Robert Browning poem: it takes metre, it takes some of the lines from that poem. Browning was definitely a big model for me, especially in the early stages of writing. There’s certainly a lot going on in the book between wanting to be a model disciple and also wanting to cast off that relationship. And I don’t think you can actually have it either way. You can’t. If you’re writing in English, you can’t. JN: I want to ask about that tension as it applies to history, and where you as a writer would situate yourself in history. Do you feel like a writer has a responsibility to situate themselves in history a certain way? MP: I’m not sure. I think as a writer you have the responsibility to form your own personal canon; that’s the responsibility of any writer. And I think when you’re doing so you have to do your best to be conscious of all the different traditions and canons out there. For me, it was the English canon—the capital-E English canon, British survey courses in second year undergrad kind of stuff—a lot of that is what really spoke to me, what I really love, and what I came to love about poetry. It was interesting to me that some of these poems were the same ones that my grandparents encountered in school (at least until they were wrenched out of it because of the interment). I found myself much more interested in subverting that ubiquitous, hulking English canon from within, I think, than trying to demolish it entirely: there’s so much to steal. JN: Do you think those comments would transfer over to talking about political history, as opposed to just literary history? MP: In what sense? JN: You were talking about the journalistic perspective you took on in “Tashme,” and I thought that came out really powerfully. One thing that struck me throughout the book is that you take up some historical events that are very politically charged, that for a lot of people would be an occasion for outrage, yet it seems like your response is normally something more like openness. You even mentioned confusion—I don’t know if I’d go that far, but there’s at least a kind of wondering what’s next or where this goes, and not developing answers. MP: I try to resist answers a lot of the time, because answers put an end to something. If you can speak an answer to something you’ve ended it, and I don’t think any of these issues have ended; they’re ongoing. Perhaps other people look at history and they want to have an answer, they want to respond in a certain, pointed way, but that’s not my experience of these things. And for me, personally, I think part of that has to do with the generational distance and part of that has to do with my particular family’s ethos. When applying that directly to political history, it becomes a little more difficult and problematic. But I think it’s something art can do that I don’t think you can do all the time or in the same way with history and politics, which demand conclusions, even though we might have to continually revise them. I mean, my approach to history in this book was through my family, and I’m not sure I can make any claims beyond my relationship to the poems and my relationship with my grandparents, my parents. JN: This reminds me of a short passage in “Tashme,” about how one of the museums you visit contains objects donated by former residents of the internment camp: some of these former residents are still alive, and they frequently come to the museum to “visit their possessions turned artifacts.” So, on one hand we can look at these artifacts and say, “This was a historical event, we have to decide this was outrageous, we’ll never do anything like this again.” But on the other hand, this isn’t at all done with, there are still questions being raised, and there are still inheritances that haven’t been sorted out yet. MP: They’re looking at these things that have been relegated to history, but the history doesn’t end. The history doesn’t end in any way, and it never will. For me at least, it’s hard to say that I’m looking back on something when it’s something that’s surging past me, around me, and will be going on after I’m gone. JN: We talked about unexpected or surprising images, how they come into the logic of these poems, and I feel like that’s often the case with the appearance of modern technology and pop culture in your poems. One of my favourite examples is also in “Tashme,” where your grandfather goes to buy a souvenir from a local welcome centre (which is steeped in all this heavy historical discourse) and comes back with a Neil Diamond CD. MP: I think there’s an authenticity to these objects, and what’s problematic is that we often assume there isn’t because they’re pop culture objects. But I’m not so sure. My thing is that I hear more about Kanye West than Wordsworth in my everyday life, so why wouldn’t Kanye West be in the poem? To me it’s a way of situating myself in a certain temporality. But that’s not the point of any poem, really; it’s just that these objects and people are there. JN: The way I see it, these objects always end up picking up the same thread that the poem was following about all along, and often that thread can be spoken without reference to them. I guess you could say that thread is something timeless, something you could imagine coming up in a poem that’s a hundred years old. MP: Right. And when you read Robert Lowell, his poems are entirely grounded in things that are happening, objects, events of the time. Same with Bishop, same with a lot of people. And I’ve had people ask “Why did you put that in the poem? Don’t you want your poems to be timeless?” I think that’s interesting, because I don’t know if that’s relevant to the poem’s timelessness. I’m glad that, for you, the references didn’t feel ironic or irreverent—I honestly didn’t want them to be. They were just organic pieces of the tapestry of the poem, or of my experience. JN: I always felt like they came up in service to something more real. MP: Well, that’s always the point. They’re like any part of the poem: they’re in service to something. They aren’t there for the sake of themselves. MICHAEL PRIOR |

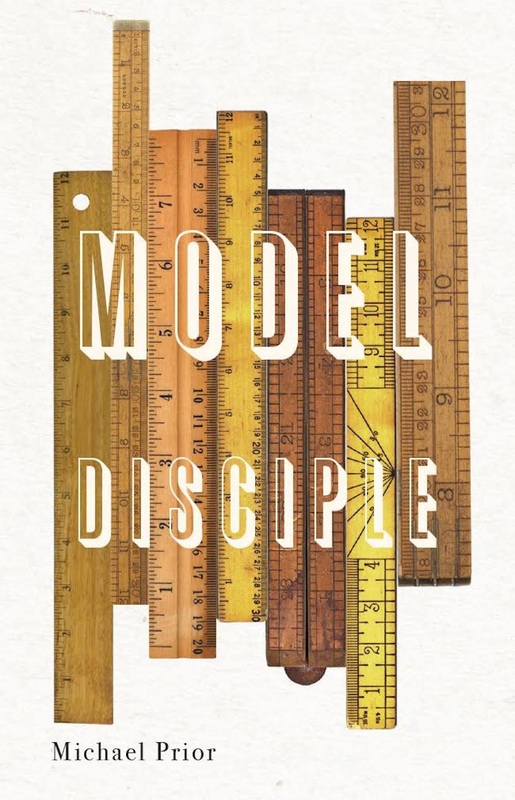

| Description from the publisher: A mesmerizing and moving first collection, Model Disciple gives us a poetry of two minds. Confounded by Japanese-Canadian legacies too painful to fully embrace, Michael Prior’s split speakers struggle to understand themselves as they submit to their reinvention: “I am all that is wrong with the Old World, / and half of what troubles the New.” Prior emerges as a poet not of identity, but identities. Invented identities, double identities, provisional identities—his art always bearing witness to a sense of self held long enough to shed at a moment’s notice. Model Disciple’s Ovidean shape-shifting is driven by formal mastery and |

Necessary Omens (from Model Disciple)

I bore her. If difficulty is a virtue

then we might be saints. Who was it

that once equated virtue with moderation?

Kanye West, I think. Most quotations

may be attributed to the internet, plagiarism

being just an ugly way of remembering

a pretty thing. Once, in a city grown

from the rich mud of a river’s delta,

I watched chrysalises suspended among

magnolia branches, more spectral

than prescient of birth. I had walked

that way every day and not noticed

until a friend diverted my sight. I felt terrible,

knowing it was my duty to look up

occasionally, to keep one eye trained

on what couldn’t be controlled. Like the time

my sister let her guinea pig out of its cage

and a hawk dropped down from the clouds

and took it. The future had arrived.

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed