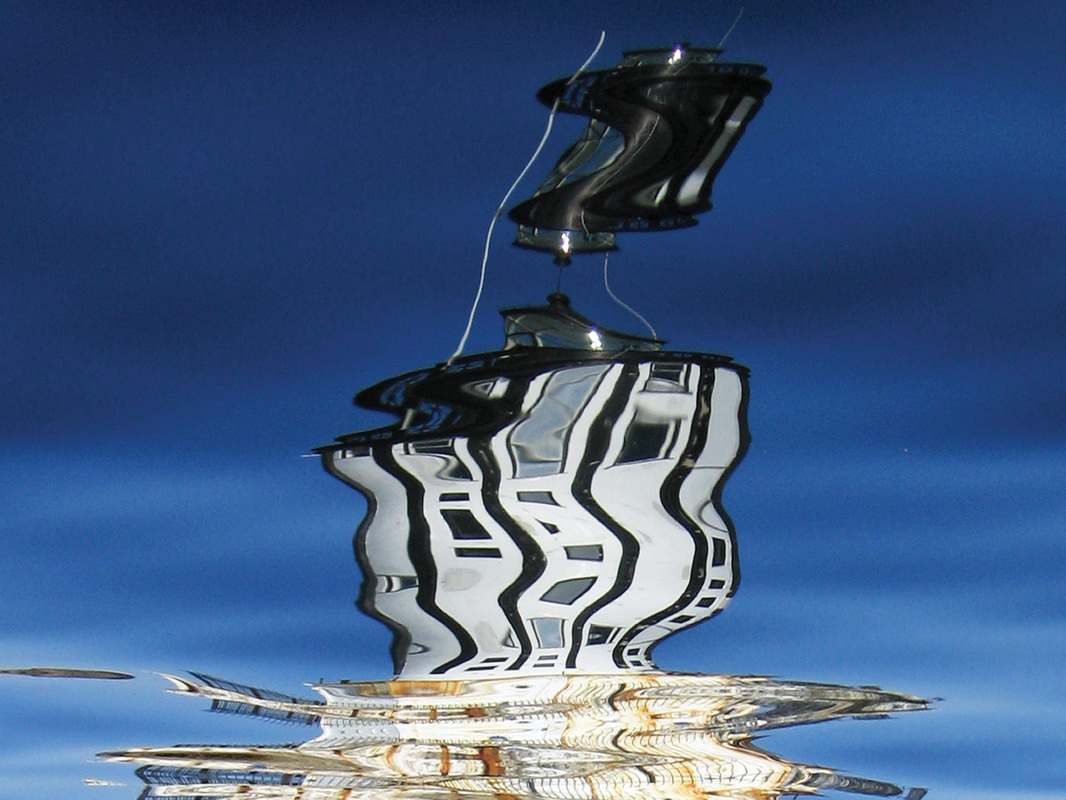

RUSTY TALK WITH MIKE WATT Mike Watt Mike WattPhoto Credit: Carl Johnson History Lesson: An Interview with Mike Watt Mike Watt played bass in Minutemen, and for that his place in musical history is assured. However, Watt is not a man to rest on his laurels. When he turned 57 in December of last year, he'd recently completed a 51-shows-in-51-days US tour with his band Il Sogno Del Marinaio (his two Italian bandmates are in their 30s). Earlier in 2014, he toured Europe with one of his other bands, Mike Watt + The Missingmen, and after a flurry of US shows at the beginning of this year he is now back in Europe with the Missingmen, this time touring his third “punk opera”, Hyphenated-Man. He’s released 5 albums in the last 4 years on his own clenchedwrench label. He hosts a radio show and podcast called “The Watt from Pedro Show”. He publishes extensive tour diaries on his website, a rich self-archive he calls hootpage. He also makes albums and tours the world with the Stooges, for whom he has played bass since Iggy Pop reformed the group in 2003. So if you wanted to call Mike Watt the hardest-working man in punk rock, there would much to back that up. It’s a title Watt himself, with his stubborn prole modesty, would probably take some pride in. However, to do the man justice you’d have to expand on the terms employed. Watt doesn’t just work the bass back and forth from stage to studio, he also works up and down, plumbing depths and scaling heights. While musicians reared on Minutemen are already embarking on reunion tours, Watt remains restless and forward-looking, constantly challenging himself with a range of new projects. All this to say that hard work, for Watt, doesn’t simply mean pounding the pavement and honing his craft—it also has something to do with artistic renewal and growth. Then there’s the question of what is meant by punk rock. Minutemen were founded in 1980 by Watt and his childhood friend, guitarist D. Boon, in their hometown of San Pedro, California (drummer George Hurley completed the trio). While the band was among the pioneers of the West Coast punk scene, their distortion-free sound was never exactly what most people thought of as punk music. Minutemen’s brilliant run came to a sudden, tragic end in 1985 with D. Boon’s death in a car accident. Watt’s subsequent output in bands like fIREHOSE, Dos, and others has veered even farther from the strict genre of punk, but as Watt points out, for him and D. Boon punk was an idea more than a musical style; it was an ethos, a politic, a practical philosophy, a movement. Few bands put this idea to such inspired use as Minutemen, and fewer people have remained as fiercely, and productively, committed to it as Watt. My excuse for proposing an interview was that I had recently read and admired Watt’s 2012 book Mike Watt: On and Off Bass. It pairs his handsome digital photographs of San Pedro with excerpts taken from his tour diaries, which are written in searching chunks of rhythmic, Beat-like poetry-prose.

Literature and art have long been important influences for Watt. He refers to his three song-cycle solo albums as punk operas, and in their way they are literary as well as musical works. Contemplating The Engine Room (1997) explores Watt’s personal and family history through the multi-faceted metaphor of naval life (his father was a sailor). The Secondman’s Middle Stand (2004) ruminates on a period of serious illness Watt underwent in 2000 through references to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Hyphenated-Man (2011) is a kaleidoscopic self-portrait inspired by the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. As we were wrapping up, I asked him what he’d been reading lately and he proceeded to rattle off a diverse list followed by characteristically to-the-point capsule reviews. Some of the books included a collection of interviews with Ivan Illich (“Interesting cat”); 1776 by David McCullough ("I was thinking this is a book that somebody would give D Boon. That’s why I read it … but it was kind of lame.”); Beatrice & Virgil by Yann Martel (“It ain’t about fucking Dante I’ll tell you that.”); The Master and Marguerita by Mikhail Bukakov (“That is a very good book. I really liked it.”); The Pillowbook by Makura no Sōshi (“Yeah, it’s basically something like aesthetics – here’s what I like, here’s what I don’t like. Really trippy.”); and books about Stalin and Mao ("Fuck, talk about trudges … 800 pages each.") A conversation with Mike Watt is a history lesson in the best sense. He is aware of how rich his past is, and he’s given it much thought so he is happy to talk about it – sometimes fondly, sometimes not, though he never sounds nostalgic or bitter. Speaking in the same singular vernacular that features in his writing, he is blunt and self-deprecating and enthuses easily. His energetic mind roves happily and rapidly, embarking on top-of-the-head riffs that can initially seem like unrelated tangents but eventually reveal themselves to be variations on the themes he is always circling: writers and artists; punk rock and D. Boon; peddling, paddling, and Pedro. Our conversation took place via Skype last in December and has been edited and condensed. MICHAEL VASS: How did your book On and Off Bass come about? MIKE WATT: It comes from an art show I had in Santa Monica a couple years ago at Track 16 Gallery … Well, let me start at the beginning. In the ‘90s, Columbia, the label, gave me a [digital] camera to bring on tour. Using one of these cameras, you don’t have to buy film. You can take chances and if the shot is lame you just delete it. This was just a whole other sensibility. I’d had a photography class in, I think, the 10th grade, that’s the only kind of picture-taking experience I had. So I came back from tour with this camera, and around the same time I started riding a bicycle again after 22 years. I don’t know if you know where San Pedro is, but it’s a harbour of Los Angeles, so we’re trippy for So Cal. We’re very much a working harbour. MV: Not a beach town. MW: No, not really. But it does have nature. It has these cliffs, the end of the land is here, mixed in with these docks and hammerheads and cans and big boats. So I started taking pictures with this camera. And then, about four or five years of that and my knees were killing me, so I started doing kayak. Point is, when I’m not on tour and I’m in my Pedro-Town, I’m up at the crack of dawn, in a sound kind of mind. I’m trying to capture it with pictures. I’d float these [pictures] around to my buddies on my email list. Laurie Steelink said, "Oh, we should print some of these.” I said, "Like which ones? Here I’ll give you a bunch and you just pick." So she picked these out and put them on the wall of this gallery, Track 16, and people came … It was a trip, I’d never done anything like that. A couple people at the show were Kat and Peter from Three Room Press in New York City. They were thinking, "Hey Watt why don’t you put this in a book? You do this diary when you’re on tour. So we’ll juxtapose diary entries when you’re out of Pedro against pictures with you in Pedro." I said, "OK, you go up on hootpage, you see all my diaries, you take the excerpts you want." So both situations, pictures and the spiels … I mean I did ‘em all, but I didn’t really pick them. So in a way, it’s kind of curated, or edited. MV: So you put all your tour diaries online? MW: Yeah. To me in this day and age, I don’t know what you guys think, because there is something about a book … But you put it on the internet and in a way you’re publishing it too. MV: Yeah, of course. MW: OK, you agree then? MV: Well, The Rusty Toque is an online journal. MW: Ah OK, so none of it’s hard copy? See that’s the way … People were telling me, "Man, you should print up these diaries!" I said, "They’re already published when you put them up on the fucking internet, people!" MV: Did they run their decisions by you, about which photos and diary entries they chose? MW: Maybe I had some little opinions about things. But I wanted some kind of objectivity, because I’m too close to this shit. I didn’t take those pictures or write those diaries to become a book or an art show. So I felt I didn’t have enough perspective. You know, I was new to this kind of field, so I didn’t have the confidence. I didn’t want to come off as so self-important, like I knew exactly what people wanted to know about me. Actually, you know, it’s my second book. MV: There was a book printed of your Minutemen lyrics, right? [Spiels of a/ d’un Minuteman, published by L'Oie de Cravan] MW: Yeah, the words I wrote for the Minutemen. In fact, that’s from your parts, Canada. MV: From Montreal … MW: That’s right. A little publishing company that puts out poetry. They did a translation, every other page is the Quebecois. The Minutemen were using a lot of slang ourselves, so I thought that was neat. We all get kind of provincial in our talking, our slang. At the same time language is for communicating, you know? By reading those words you might get a sense of what it was like to be in a band with D. Boon and George Hurley. That was my idea with that. I even put my first tour diary in there. I wrote one because it was the first time the Minutemen went to Europe with Black Flag. Man, I was really bad at it. Actually, diary writing – there’s kind of a technique to it. MV: How did the diaries start for you? MW: I do it on tours for a couple of reasons. One is just to keep it together, keep focus. Another one, I am writing for younger people—not to be their eyeballs, but to inspire them to get first hand experience. This idiot old guy in Pedro, driving around and working bass—if he can do it, you can do it too. The reason that I’m into that is I still consider myself part of the movement. And I owe the movement. The movement was so loose and autonomous, they let people like me and D. Boon living here in Pedro put on a gig. And Greg Ginn at SST – we were SST 002, the second SST record. That was an incredible opportunity that the movement gave us. I feel a debt. Since I was allowed to let my freak flag fly, I wanna turn people on to the same kind of trip. MV: So going back to the diary writing – how has it changed for you? What are the techniques you learned? MW: Well, the biggest enemy of diary writing is memory loss. Especially when you tour the way I tour, because I play every day. So you’ve gotta do it the next day. If you get behind, everything blends into the same fucking thing. Each day is unique. I mean, you can get all reductionist, you know: woke up, took shit, took piss, ate chow, drove to gig, did gig, conked … repeat. You don’t wanna do that. You wanna build in the nuances of the minutia, and still fucking live your life. You gotta do it kinda recent to the event so things are fresh. You gotta try to not write the same fucking thing every day. MV: So you’re pretty disciplined about it when you’re on tour? MW: Yeah, try to do it every day on tour. It really helps me focus and play better. Diary worked out for me like that big time. Especially when I’m thinking, where did I blow clams? Can it go better? What stupid fucking things did I say? It’s kind of a self-critique thing too. You use your own self as a sounding board. I’ve heard of these kinds of techniques people do in therapy, they’re asked to do diaries. MV: Right, I’ve heard of that too. MW: So who knows … Even when Mr. Poe or Mr. Twain or Mr. Whitman, even when they were doing their trips, who knows. That’s what’s trippy – about the work, the person, the reason for the reason, the technique … That’s why human expression is interesting to me. Besides being fabric that kind of connects us, it’s also a way for us to express ourselves, like our fingerprints already do, but at the same time, kinda resonating on the common ground we all share. So what’s important at the end of the day with the diary shit is doing it. What is it D. Boon would say-- “The knowin’ is in the doin’.” That’s the diary idea. Now the other way I write words is for tunes. And that’s a different trip, because you’re trying to serve the tune. I usually always start with the title. Just like with the diary you always start with the date. I need some kind of form. MV: You start a song with the title? MW: Always. Because it gives me some kind of focus. I’m not saying everybody’s gotta do it that way, I’m just telling you … Shit, I never thought I was ever going to be doing this. I got into music to be with D. Boon, I wasn’t really a musician. And uh, yeah … he got killed, and I kept going. I’m still a student. MV: Had you written anything before the Minutemen? MW: When I was a teenager I wrote one thing. It was called “Mr. Bass, King of Outer Space”. [Laughs] I can’t remember the music or even the words. But I do remember the plot, or whatever you want to call it, of the tune was I do a big bass solo and blow everybody off the stage. [I was] socially kind of insecure. I’d learned about bass hierarchy, that it’s where you put the retarded friend. It was like right field in little league. Nobody D. Boon or I knew wrote songs. I’m 13 in 1970, so we’re ‘70s guys right? In the ’70’s culture there’s no clubs anymore, that ended with the ‘60s. Now it’s arena rock. So the performances are like Nuremberg rallies, there’s no empowerment. You’re sitting so far away, the band is tiny, all the lights … That’s not empowering. That’s like you’re at the fucking circus. It was much different when punk, when the movement, came. It made everybody in the band way more equal. And especially with a guy like D. Boon. He wanted to put the politics … They weren’t just in the lyrics, they were in the way we made the music in the band. D. Boon was really heavy about that, which I’m glad for. Like he learned from R&B that the soul music guys would play really trebly guitar, really clipped, no power chords. So [by making his own guitar really trebly], he was making room for the bass, making room for the drums. He said it was like an economy, he wanted a more egalitarian economy. MV: What did you think of that? MW: It was trippy at first, we’re young men, you know. But punk was so fucking profound on us, it just made us rethink everything. Nothing from the arena rock experience. I think this is one of the things that made us embrace the movement even more. When the hardcore kids came out a few years later in the early ‘80s, they weren’t really rebelling against the old rock because they never knew it. In a way, we were much more reactionary than those guys. MV: So when you started writing, you’d think of a title and go from there. MW: If I got the title it would give me enough fucking focus that I could either bring the words in, or bring the music in, or bring them both in, so that—at least in my idiot mind—they would make some coherent sense. I say that because D. Boon would say that my lyrics were too spacey. [Laughs] You know that’s why on Double Nickels on the Dime I’m reading that landlady’s note (on “Take 5, D”). That was kind of—not a rebuttal, but me just having some fun with him. “OK I’ll try to be more clear here, more real, more real.” At first we thought words were kind of like lead guitar or something in songs. It was mysterious what words were about. But when we saw the punk gigs … I remember D. Boon coining this phrase “Thinking out loud.” Ah – that’s what they’re for! You can actually use the music to express thoughts, feelings—that was totally new to us. Before that it was all about trying to copy some licks or something. The idea of using art—and I’m talking about poems, painting, all this stuff—to express stuff … It sounds naïve, but man that was a huge mind-blow for us in the ‘70s. MV: You guys were also teenagers, that stuff blows a lot of teenaged minds. MW: I also think that the stuff from the ‘60s had gotten forgotten already. Everything goes through these cycles it seems. I think we were in this time that was very much: “Well, we’ll take a couple people, they can be the elites and speak for us all.” And I think when the movement came, just like the Beat thing, and before that people like Woody Guthrie, before that people like the Dada people … It’s sort of like farmers and fertilizer—if you want a good crop, use a lot of shit. It seems like you need these things to inspire other kinds of reactions. Even though it was a really fucking lame and stupid time, we were also very lucky. The Minutemen was in a very lucky place because no one knew exactly what to do with the movement, so you could help be part of that invention. Every time is a good time to be born, but for the Minutemen graduating high school in 1976 was just so lucky. MV: Back then, how did you guys approach the musical side of things? MW: Maybe us learning the Blue Oyster Cult and the Creedence helped us a little as far as getting licks together. But we thought that was really secondary. That’s what punk rockers taught us. Bands like the Urinals—the song’s all one chord! We thought that was so fucking econo … What’s the other word for it? Elegant, elegant. You just need enough. Like when you see a Vincent van Gogh painting there’s not too many strokes, there’s just enough. Socially that opened us up to a whole bunch of wild people too. Those people in the early punk scene, they all were very deep. They were strange and weirdos, and that’s why they invented this parallel universe. But they were very interesting and inspiring. Now, down the road 35 years I’m talking to you. And it’s all because I was in a band with my buddy, and I was part of this movement. Actually, me and you probably have more common ground than a lot of my peers did in those days. MV: Were you guys reading a lot back then? You mentioned poetry was inspiring. MW: Yeah, yeah. As a teenager I was huge into the Divine Comedy. MV: Already as a teenager? MW: Yeah, I don’t know why. It was like some kind of puzzle to figure out. All the names, all the people, all the fucking weird-ass stuff, you know? Punishment, atonement, reward or whatever the fuck—trying to make sense of this shit. I don’t know how I stumbled onto it. It was in the 10th grade, so maybe 16, 17? So that was the first big poem I got into. Around the same time I got into Huck Finn. Before that I was reading a lot of science fiction. You know I’m born in ’57, so when I’m a boy it’s all about the space race, the Soviets and US. So I was reading a lot of this stuff, Ray Bradbury, Mr. Dick, even some [Robert] Heinlein, Frederik Pohl, and Roger Zelazny … these science fiction things. The other thing was dinosaurs, I was into dinosaurs. So I think this was one reason … Well, what happened was my mom got me this World Book encyclopedia, the door-to-door guy sold us these encyclopedias. They start from A and go to Z. So when I got to the Bs I found this guy Hieronymus Bosch, I think that might have steered me toward Dante too. It was so bizarre, all these little creatures – which kinda reminded me of the dinosaur stuff. And D. Boon got me into history, that’s what he read. I wasn’t that much into non-fiction, I liked fiction. MV: He read more non-fiction? MW: D. Boon read almost totally non-fiction. I can’t remember any fiction he read. So that influenced me. I got into that stuff because I wanted to talk about what he was talking about. He liked history a lot. As far as fiction, well because of the punk rockers teaching me, like Raymond Pettibon, I found out about Jim Joyce. So I got really big into Ulysses. In fact, almost all of my songs on Double Nickels on the Dime are inspired by Ulysses. Writers started to become a big source of inspiration for me. And the poet I was into at the beginning of punk was Rimbaud. “The Drunken Boat”, A Season in Hell, “Democracy”. I even put music to some of these things, even though he’s writing in fucking French and I’m reading translations. But this idea where he had colours for the vowels … I was just at a very impressionable time, that thing where anything goes. As I was saying the movement was profound. So I got into all this kind of literature, wild-ass stuff. A Bohemian kind of thing. The Beat people – Mr. Burroughs, Mr. Kerouac, Mr. Ginsberg’s Howl, Mr. Pynchon. I guess he’s more psychedelic, with Crying of Lot 49, and then Gravity’s Rainbow. The 60s thing … See I’m a boy in the ‘60s. ‘69 I’m 12 years old. It was a strange place. I saw a lot of things. I saw Mr. Oswald shot to death on TV. I saw people on the streets for civil rights, taking things into their hands about wanting change with the war in Vietnam. I’m in Pedro because of Vietnam, ‘cause my pop’s a sailor. So I am kind of a product of those times. I’m not really a ’60’s person, but it did have a huge influence on me I think. Just as, in a weird way, I’m not a ’70’s person either, but the ‘60s and ‘70s really grounded me. Made all my sensibility. Made me really encouraged to go for something and refuse another thing. And wanting to get in on this, I don’t know … further, beyonder, you know, the Last Poets. [Laughs] I was really into Last Poets. It’s trippy how rap came out of that. It made total sense to me when that happened. Kinda like black punk. One thing about being a ’70’s teenager, [it was a] pretty narcissistic generation. You didn’t want to know about stuff that was 5 years older. It was really weird. We were all about ourselves. When I look back on that now, it was ridiculous. Very self-satisfied. I think it was because some of the counter-culture of the ‘60s got co-opted by commercial things in the ‘70s. And I think some people thought this was some kind of victory. That all the work was done. So thank god there was this tiny little movement that me and D. Boon fell in with, and music was one of its components. A lot of the dudes you could tell were not musicians. A lot of them were artist people. They were provocateurs. They wanted to make points. They wanted to be a little adversarial, a little confrontational. And then you know, this was kind of pushing buttons from our earlier programming seeing this [civil rights] stuff in the streets on the TV. It’s very interesting. We couldn’t really articulate it, but I think it does come out in our work. MV: Yeah, I can see that. MW: You know, McCarthy--a band on a record in 1980 talking about McCarthyism … I mean, this is just bizarre. But that’s what we were feeling. The new boss was Mr. Reagan. I think you guys had Mr. Mulroney, and over there in England was Ms. Thatcher. MV: That’s surprising to hear that your interest in both Bosch, who you used for your Hyphenated-Man album, and Dante, who you used for Secondman’s Middle Stand, stretches all the way back to when you were a kid. MW: Yeah. Richard Meltzer says that I’m his favourite sentimentalist! [Laughs] Maybe it’s weird going back to little boy shit. MV: Dante and Bosch isn’t really little boy shit. MW: [Laughs] Well, I mean my boy experiences. I’m not saying the subject matter. In fact, I was told by a high school teacher that I shouldn’t be reading that shit. Some lady at San Pedro High. She wasn’t an old lady either. “This ain’t a story for a young man”. I said, I’m sorry, but I kept reading it, I wasn’t gonna stop. In fact, I read different people’s translations. The Ciardi was the first one, but then I found the Longfellow one. There’s different ways to try to do it – with blank verse, or to try to keep the little three-rhyme thing going. In a way, it was like playing with a fucking Rubik’s cube, you know? It’s very fascinating to me. I don’t know about the subject matter so much. But the work itself is really fascinating. Just looking at anything and taking it apart. MV: With Hyphenated-Man, for example--I know that was also partly inspired by when you participated in We Jam Econo [a 2005 documentary about the Minutemen] and started listening to Minutemen songs again for the first time in many years. MW: You’re right. MV: Did the Bosch connection just kind of pop up again then? MW: No … I was on tour with the Stooges in Madrid at the same time that I’m listening to the Minutemen, in 2004—actually it was the 400th Anniversary of Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote, another great book, they had a big festival. Anyway, the hotel we’re at is right next to the fucking Prado. Prado’s got 8 Bosches. I couldn’t find them at first because they call him El Bosco. But I found El Bosco and saw them in real life for the first time. And it’s not like a picture in an encyclopedia, man. In fact, he painted on wood, they’ve got no glass so you can put your face right up there and see. And it blew me away. For some reason having this experience of re-listening to the Minutemen, I thought man this [Bosch’s work] is like a Minutemen album, or Minutemen gig, a bunch of little things to make one big thing. MV: That makes sense. MW: You know what happened? When I started hearing the Minutemen, I wanted to play music like that again. But then I owed it to D. Boon and Georgie not to rip them off. So I thought to myself, what if I made another opera, and I’ll write about something the Minutemen would’ve never wrote about—being a middle-aged punk rocker! [Laughs] So that became the libretto. I felt OK about that. I wrote the whole thing on D. Boon’s Telecaster. I’m not that much of a guitar player, but I did it on purpose so the bass would come second. I was doing all these things so it wouldn’t be too much Minutemen, because I was feeling guilty about ripping my old band off, you know? There’s too much of that shit going on already. I don’t have to be another one doing that. So what I did is I tried to use that as like an appropriated thing, to make a new thing. MV: You wrote all the guitar parts first? MW: I wrote the whole thing, all 30 parts on D. Boon’s guitar, his Telecaster. You know, symbolically, it was very emotional. Talking about yourself is a fucking scary thing. You gotta lay it out there, but it’s still gotta be a fucking song. So I wanted to bring things out, be brave enough to say ‘em, but still be artistic with it. And D. Boon was a painter, you know, besides a guitarist and a singer and a songwriter. So I thought that he would just somehow help me, by using his machine. I even have the demos, all 30 of them. I recorded them all. I’m glad you brought that record up, because that’s a real important one in my mid-life. It’s one I never would have thought of as a younger man. I thought it was all downhill after Double Nickels on the Dime. [Laughs] I wasn’t trying to do another Double Nickels on the Dime. I was visiting some earlier place in my earlier music, but I was trying to talk about something very contemporary, my life right at the moment. I even wrote it in order. Though at the end of the day I took the middle song and put it at the end, because the last song [“Man-Shitting-Man”] turned out to be a real downer. The way the mind works – just like looking at those Bosch paintings, they read from left to right – people might think that “Man-Shitting-Man” is my kind of, I don’t know, conclusion or summation of the whole trip. It’s not. Middle age is about reconciling a lot of things, but there are some things you can’t reconcile, and a lot of that is man’s inhumanity to each other, the way we treat each other. There’s no good reason for it, ever. And I had acknowledge that or else I wasn’t telling all the truth. That’s why I had to have “Man-Shitting-Man”. But I didn’t have to have it last. MV: Have you ever had writer’s block? MW: Oh yeah, it can come. It’s one reason why I used other people’s words. If you look on Double Nickels, they’re not all Boon/Watt/Hurley. If I used other people’s words, all of a sudden I’d get different licks coming out of my bass. Writers’ blocks, they come. There was a period in the early 2000s after that sickness. I had to tour a lot to pay off … You know about our incredible, wonderful medical system? $36,000. So I had to do a lot of tours. And I was happy to pay it off, because I was alive. [Laughs] But I had to play gigs where I was doing lots of cover songs … I was going through a little blockage period. Between the first and second opera. MV: So the Secondman’s Middle Stand was hard to write? MW: Well, it was easy to write because it was about that fucking sickness that almost killed me. I used the Divine Comedy as a parallel. The sickness was the Inferno, the healing was the Purgatory, and getting to ride my bike and kayak and play bass, that was Paradise. I wrote it pretty quick, but in the meantime I had to pay off these debts and do a lot of touring. Two tours a year. Bands like the Jom and Terry Show, The Pair of Pliers … I mean these bands didn’t even make albums. I put them together just to tour, just to get the money. So the one good thing was, even though I had some writer’s block, I was still performing. That’s kind of treading water a little bit, but it’s better than doing nothing, like putting the bass down. MV: Finally, if there’s one word you’re associated with, it’s "spiel". Where did that come from for you? MW: It’s Yiddish. A lot of show business talk is Yiddish because a lot of these cats—well fuck, they created the culture! There was a time with no TVs and theatres right, and so cats had to travel town to town ... Vaudeville. And in a lot of ways I feel very connected to this culture. The touring life, you know? I play rock and roll music, but the touring and that part, that’s way more into vaudeville culture. So I use a lot of these Yiddish words—I think it was a mix of Hebrew and German, with Polish and Russian. It comes from Jewish Europeans who immigrated over here and worked in theatre and then movies and in music too. Entertainment culture. I got to play with the Stooges in Tel-Aviv and it was trippy, the young people there didn’t even know what Yiddish was. They speak Hebrew. So it was specific of a certain kind of people at a certain time. But this idea of workin’ the towns—you could say Shakespeare was [doing that], I mean all kinds of people were in this tradition. So spiel comes from this. And shtick, and kvetch and kevel and schlep. All these words come from this tradition I see myself as part of. MV: But “spiel” was a Minutemen word too. You guys were using it already back then. MW: Spiel was like your pitch, trying to sell somebody something, not an item so much but a point of view. And it doesn’t have to be jive. Of course some spiels are jive, but some spiels have a lot of integrity. I think the Minutemen used it for a self-humiliation thing. I told you, we were pretty insecure about lyrics—we didn’t even know what they were for. So if you were already making fun of them, maybe you’d be a little more brave to do it. So that’s why we called our lyrics spiels. Also, interviews we called spiels. Every time you opened your fucking mouth that was a spiel. MV: Well, it kind of goes with D. Boon’s “thinking out loud” idea. MW: Absolutely, absolutely. These things were empowering to us. It was a form of expression, a kind of power for little guys like us. Not power over people, but power to be creative.

Michael Vass is filmmaker and writer and a regular contributor to The Rusty Toque.

Comments are closed.

|

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor: Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed