RUSTY TALK WITH VICKI LEAN

|

"Canadians like to think we have this loving, egalitarian wealthy society. But we don’t. We have communities that have the highest suicide rates in the world." |

Victoria Lean: I was making bizarre home movies with my neighbors from when I was about eight, and I wanted to be a professional documentary filmmaker ever since I was a preteen. My parents are environmental scientists, and I spent a lot of my childhood at their field station (on a lake) where many other scientists and grad students would visit. The rest of the time I was in downtown Ottawa. Growing up in the country’s capital, I felt there was a profound disconnect between academics, politicians, activists and the general public on the kinds of environmental issues my parents and their colleagues were studying.

Believing that film and media held the key to dialogue and change, I pursued an undergraduate degree at McGill that straddled film studies, international development, and environmental studies. Through this more activist approach to filmmaking, I fell in love with craft. Living in Montreal for my undergrad, I was shooting and editing music videos and live shows, including an experimental short for the NFB.

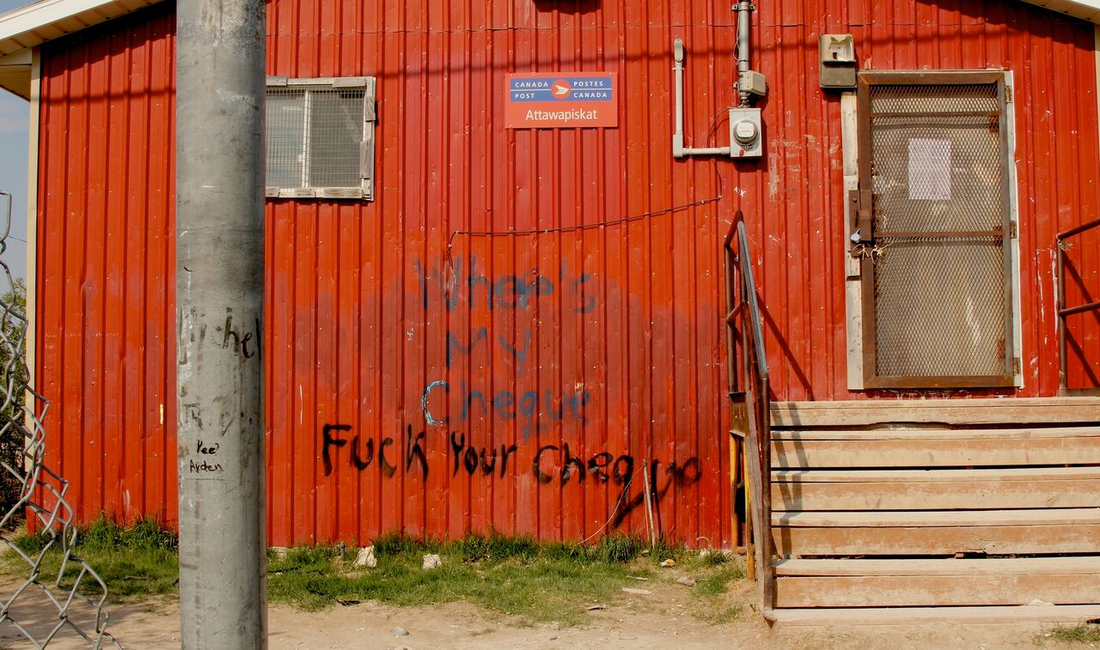

Soon after completing my undergrad, my dad brought me along on a visit to the remote First Nation’s community of Attawapiskat in Northern Ontario. After witnessing the tremendous injustices facing the reserve, I decided to assist in the community’s efforts to raise awareness of their situation.

I embarked on an MFA in Film Production at York University to develop what would become After the Last River. It is pretty much my first film as I have not submitted anything else to a film festival before. I had no idea what a challenging, but hugely rewarding, journey it would be.

MV: So you first became aware of the Attawapiskat community through your father’s work?

VL: Yes, that’s right. My father, David Lean, is an ecotoxicologist and freshwater scientist who specializes in mercury release in wetlands. Over a decade ago now, he started raising concerns about the De Beers Victor Mine, which is still Ontario’s first and only diamond mine, and how it would be draining large amounts of water from the wetland, resulting in potentially higher levels of mercury in the fish eaten by the local community.

Around 2008, he was going to be an expert witness in an Application for Review filed under Ontario’s Environmental Bill of Rights that challenged the De Beers project—but it didn’t go forward. The pro-bono environmental lawyers involved at the time explained to me how hard they found it to represent people in the far north—both because of geography and language barriers. Two weeks after the mine opened, I went on that first trip to Attawapiskat with my dad and two environmental groups, EcoJustice and Wildlands League. Concerned community members had invited them to discuss potential environmental impacts from the De Beers mine, especially those involving mercury levels in the local fish.

MV: What drove you to make a film exploring these issues?

I made After the Last River because I wanted to help bridge a large gap between different groups of people—driven far apart by geography, language, culture, histories and experiences of colonization.

In the early days of the project, I was specifically drawn to investigating the environmental issues surrounding the Victor Mine. Before the diamond mine opened, the Attawapiskat River formed part of the largest pristine wetland in the world. The deep layers of peat in the James Bay Lowland store 26 billion tons of carbon, which contributes to roughly one tenth of the globe’s cooling benefit. This was also one of De Beers’ first mines outside of the African continent, so that was interesting to me given the company’s troubled history.

When the mine opened in 2008, I witnessed the Victor project receive little media attention and arguably inadequate government review, and so I returned in 2010 to document the impacts of the mine on the community—both the negative and the positive.

However, upon arrival, I realized the deeper story was beyond my environmental lens. It was rooted in the vast disconnection between the reality of Attawapiskat and the myth of Canada. Attawapiskat struggled to benefit from economic development opportunities such as the De Beers Victor Mine because of factors beyond what a mining corporation can address—a lack of housing and social services such as family counseling, health care, youth programming, and education.

MV: What was the first step in terms of getting the film going?

VL: My first step in 2010 was getting permission of the Chief at the time, and then finding a place to stay and finding a local contact and activist working on these issues.

In creating the film, I spent over 80 days in Attawapiskat before the community shot into the national media headlines during the housing crisis of 2012 and again during Idle No More in 2013. I was deeply troubled by some of the coverage of Attawapiskat and Idle No More. The reaction of many Canadians, including Prime Minister Stephen Harper, was effectively to blame the community for its misfortune. Meanwhile, significant structural and historical explanations, such as the inability to share in resource revenue and chronic government underfunding, were hardly touched on.

One of the goals of the film is to highlight what was overlooked in the mainstream media and to draw attention to the intersection of various problems: for instance, how housing issues are also educational, health, mining, and political issues. The ultimate goal of the film is to encourage greater understanding of Attawapiskat, and to encourage southern Canadians to think about how their own wealth relates to remote First Nations communities like Attawapiskat. I wanted the film to hold up a mirror: After the Last River is not simply a portrait of Attawapiskat but a portrait of how Canada treats Attawapiskat and places like it.

MV: Were people from the Attawapiskat community reluctant to trust you as an outsider?

VL: They were receptive—but I think maybe a bit skeptical—I was this 24-year-old student when I started the film, I was there by myself—what did I know? what could I do?!

But there was a lot of warmth. People welcomed me into their homes, and Rosie and her family (who are featured in the film) certainly took me under their wing. Keep in mind when I started the film, I believed--

like many community members—that if only Canadians knew what was really going on then things would be different. People were very eager to spread awareness regardless of the medium or who was doing it.

I also had the unique privilege of spending some significant time in the community. Beyond working on my film, I joined in several traditional ceremonies, staffed the door at the high school dance, and helped distribute food donations. This activity was driven, in part, by an awareness of a long history of non-indigenous people coming to indigenous communities, asking about people’s lives, documenting their stories, leaving and then never being heard from again. As such, my filmmaking approach was rooted in investing time in making the film (five years) and living in the community (over 80 days). Before breaking out my camera, I spent time learning about Attawapiskat and participating in events and daily activities.

I believe that sharing filmmaking skills is an important means of giving back to the community. On my second trip to Attawapiskat in summer 2010, I assisted with video workshops surrounding youth suicide prevention and a garbage cleanup. During this experience, I met and hired a local youth named Trina Sutherland as a production assistant. I also organized a sharing circle between local elders in Attawapiskat and elders in Toronto over Skype as part of the Earth Wide Circles project. For the third visit, I assisted my thesis supervisor, Ali Kazimi, in collecting video and editing equipment and I led a video workshop along with my cinematographer, Kirk Holmes, to train local youth on the equipment.

MV: Is there a filmmaker or writer (or more than one) that has had a particularly significant influence on your work in general and/or on After the Last River in particular?

VL: For After the Last River, there’s been a few. While the storyline of After the Last River evolved over the years, my approach remained influenced by Susan Sontag’s last published book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). Sontag argued that when photographing dire circumstances of human suffering, the goal of the photographer should not be to elicit the sympathy of the viewer, but to encourage the viewer to contemplate how their own privilege is complicit in that suffering.

As I made the film, I thought a lot about how often images and stories relating to First Nations poverty appeared in mainstream media, but how little impact they seemed to have. Sontag proposed that "for photographs to accuse, and possibly alter conduct, they must shock,” but that shock can become familiar, people do not want to be horrified, and they simply change the channel.

In reviewing online comments on Attawapiskat news stories, it seemed that for some people, compassion was already stretched to the limit. It was my challenge to try to engage audiences that may have already tuned out, and this meant not focusing heavily on imperatives or moral obligations, but highlighting the community’s stories of resistance and strength with also some pretty awesome humor from up there.

The cinematography of Todd Haynes’ fiction feature, Safe (1995) also served as inspiration as it visually explores the presence of environmental toxins in human spaces.

MV: Your first person narration to ties together the complex intersection of issues the film is dealing with while also relating your own connection to Attawapiskat (through your father). Was it always a part of your conception of the film, or did it come later in the process?

VL: I definitely did not plan to do first person narration when I started. But after Attawapiskat hit the news, I came to recognize that a general account of Attawapiskat’s situation would not contribute much, especially given the many journalistic pieces that already existed on the community.

My own gradual recognition of the extent and complexity of Attawapiskat’s (and Canada’s) problems became a vital thread. The point of departure for story development was more about my intimate experience of the community in order to encourage a more relatable connection with the people in Attawapiskat. It was also important to foreground who I was and why I was telling this story—so that it didn’t seem like an authoritative account coming from the community itself.

Josh Fox’s Gasland provided a reference for a how a documentary dealing with environmental impacts, corporate greed, and resource extraction can be intertwined with a personal story and journey. I intended to provide a feeling of ‘bearing witness’ rather than making a direct argument. As such, my personal journey to Attawapiskat and the backstory with my father served more as a subtle, structural backbone, similar to how Eugene Jarecki used his personal story with his African-American caretaker to enter into a critique of America’s war on drugs in The House I Live In.

MV: Given the potentially problematic issues that can arise when a white filmmaker from a big city depicts a marginalized culture and community, did you have any doubts about making yourself a character in the film?

VL: I had many doubts and certainly there were many pieces of voiceover that were taken out since they felt a bit too much like ‘white girl going on a journey’. I’m grateful to my editor, Terra Long, for a lot of her coaching on that. There were also a couple stories I told in VO, particularly about a suicide attempt, that I actually removed. I didn’t think I was the right person to voice that story. Instead, that event is gestured through the suicide awareness march with no dialogue.

I always think it's important to question who is telling a story and why they are telling it. I was also questioned a lot and it was important to qualify my personal connection to the place.

But at the same time, Attawapiskat is in my own province. The situation in Attawapiskat is a Canadian problem (not simply an Indigenous problem). Part of taking collective responsibility for our shared history and the current situation, involves having the ability to respond. So this is my response to the tragedy that our country has inflicted on remote First Nations communities.

MV: In everything your learned while researching Attawapiskat and the surrounding issues (the Indian Act, etc), what surprised you the most?

VL: There are so many things that surprised me! As I followed the isolated community’s rise into the international spotlight and the Chief’s role in the indigenous rights movement Idle No More, I was really surprised by what a disturbing blind spot exists when it comes to First Nations issues.

What surprised me the most was that Canadians are deeply divided along racial lines—I didn’t realize how bad it was. Most have been taught little of Canada’s historic relationship with First Nations people; curriculums rarely mention treaty obligations or the many human rights violations against indigenous people. Historical ignorance and geographic distance have disconnected consumers from where their resources come from, and this ignorance and distance isolates First Nations from those in power and from other communities—both aboriginal and urban. Canadians like to think we have this loving, egalitarian wealthy society. But we don’t. We have communities that have the highest suicide rates in the world.

It was shocking to see how many Canadians reacted when they did find out about the community’s struggles through the mainstream media. The film wasn’t just about a community struggling to be heard anymore, but a country’s reaction to it when it finally is heard. My film definitely touches on the important role that journalism plays in disseminating information, but also on how damaging journalism can be when it’s being influenced by a political agenda or contains problematic information. So that was surprising—the level of misinformation that was getting published in important papers.

One of the themes that comes up a lot in Q&A’s is the “death of evidence.” In the case of Attawapiskat, there is very little research available on things like government funding levels to reserves, mercury levels in fish, and the relationship between a the 30-year diesel spill and the number of children in Attawapiskat with autism and leukemia.

MV: One of the most disturbing parts of the film for me was the way Harper’s PMO so effectively controlled the narrative about Attawapiskat by throwing around manipulative stats and figures to shirk financial responsibility for providing aid to the community. They suggested that the problems were due to financial mismanagement and even criminal fraud on the part Attawapiskat leaders, and the press took this seriously without much investigation into the merits of the accusations.

VL: After Harper insinuated that it was the community’s fault, that they have mismanaged the funding, the whole story changed in the press. In the resulting blame game, Chief Spence was targeted in racist comments, political stump-speeches, and op-eds. Sun News in particular was pretty hard on the community and fairly indiscriminate in their coverage—they even took photographs from the university website that I had taken during the youth video workshops in Attawapiskat and plastered “financial mismanagement” over top of them. It was horrifying.

MV: What, in your view, are the biggest misunderstandings that persist in the general public about Attawapiskat?

VL: People don’t realize there is a two-tiered system in Canada—First Nations people do not get the same opportunities and funding levels that non-indigenous communities do. They don’t have the same level of education, of housing, of access to drinking water, the list goes on. For instance, a First Nations child’s education is funded by $2,000 to $3,000 less than a child in a provincial school. And we don’t even know exactly by how much schools are underfunded.

Another misunderstanding that came up again recently, which people just don’t seem to want to shake is this tired old question—“Why don’t people move, why do they stay in these communities if they are so bad?’ People just completely misunderstand the attachment to land and the importance of community—and also that a lot of indigenous people don’t often do better away from their families when they move to the city either. For one, being an aboriginal woman in this country means you are several times more likely to be murdered than anyone else.

MV: Have you had any response from De Beers about the film?

VL: Yes! The rep from De Beers (who appears in the film) came to the very first screening, which should have been private. It was my MFA thesis defense, and it wasn’t posted on the internet, but they found out. It was a tiny screening—just me, my supervisor, two friends from film school, the two external examiners who were grading me, and then De Beers and a rep from mining lobby group, PDAC. He sent me a seven-page letter with “notes” afterward. I cried on my bathroom floor that day because I was worried my film would never see the light of day after that.

But luckily it did. And when I had the Toronto premiere, the same De Beers rep came again and when I was going into the screening he said, “you’ve had a good run so far!” I told him I got his letter and carefully considered his notes for this final version.

He sat in the back and then when the movie ended, he talked to every single Attawapiskat community member that was there on their way out, the NGO reps that are in the film, my dad, me. He said he was pleased to see some of his notes considered, and was being incredibly nice (and maybe because I’ve spoken publicly in the past by how intimated I felt by him before).

MV: This may be unfair to ask you, but it’s something I always wonder about … Even if De Beers doesn’t care about the community at all, it seems like it would be such good PR to donate money for Attawapiskat to build, say, a new school—and the amount of money would be relatively miniscule compared to the profits they are making … Why do you think they don’t do more—if only for the sake of their own image?

VL: I’ve asked them this question directly—the simple answer is that they are not in the business of building homes or schools. I’m paraphrasing, but they will say that this isn’t some developing country where government has no capacity—and it isn’t their job to replace the role of government. In some ways, they are right, it isn’t there job. And it points to just how much the Canadian federal and the Ontario provincial governments are not doing their job.

De Beers believes that jobs and business opportunities are more sustainable ways of giving back—but they didn’t fully comprehend the degree to which Attawapiskat has been systemically marginalized and how that has impacted the community’s ability to take advantage of these types of benefits. The workforce simply wasn’t ready mainly because the community never had a proper school, and also there weren’t enough homes for local workers to remain in the community (as a result many qualified people that work at the mine had no choice but to leave Attawapiskat).

MV: Can you tell us a bit about what has been happening there and with De Beers since you finished filming?

VL: The film leaves off with the possibility of De Beers expanding—of mining (Tango Extension) another one of the 17 kimberlite bearing pipes on Attawapiskat’s traditional territory.

Since the film was released, Wildlands League (the environmental group in the film) published a big investigation into the failures of De Beers’ own environmental monitoring. De Beers has subsequently reassured the community there are no significant environmental impacts. Currently, the community is divided in support of Tango Extension for a variety of reasons. Because of some local pushback, De Beers has stopped exploration of the new site that would extend the life of the existing mine, which is set to close in 2018. I understand they are already starting to wind things down—so it's sad in a way, the mine was only open 10 years and so far, it seems like the expectations for the prosperity it would bring outweighed the reality.

De Beers also build another Canadian mine the same year. And they recently shut that mine early—citing a downturn in the market. But there were some pretty questionable environmental impacts they did not foresee that played a part in it closing.

MV: Attawapiskat has been in the news again this year with the alarmingly high number of recent teen suicide attempts. Do you have any thoughts on this from your experience with the community?

VL: It’s difficult even for people in the community who have kids of their own to explain and understand what is happening. It is not a mental health issue really—it’s proven that people do not do well when they don’t have the basic necessities of life—food, clean drinking water, proper shelter, etc. As a young parent, not being able to give these things to your children is heartbreaking. On top that, the prospects for jobs and employment opportunities are dismal. Some youth have given up hope and there isn’t much to engage them—like after school programs or career training programs. And on top of that, I’ve heard that the drug and alcohol problem has gotten worse, and of course it’s very difficult to provide any counseling or support. Youth that are suicidal are sent out for psych assessment, and are back in a day or two and there is no one following up on them.

There is also some research that explains how suicide is “contagious”—especially among teenagers. Some of the worst nights in terms of the number of attempts also involved suicide pacts. It’s tragic, and its been developing for many, many years. It also has its roots in the trauma of residential school, which is often passed on through families.

There’s a lot of work that needs to be done on all fronts—and I hope the film contributes to conversations about a more sustainable and fair society in Canada.

Still from After the Last River

Still from After the Last River

AFTER THE LAST RIVER

Documentary

90 minutes

2015

Website

Screening

Canada wide – July 1, 8:00 pm EST – CBC Documentary Channel

Check with your provider for channel information.

Synopsis

In the shadow of a De Beers mine, the remote community of Attawapiskat lurches from crisis to crisis. Filmed over five years, After the Last River is a point of view documentary that follows Attawapiskat’s journey from obscurity and into the international spotlight. Filmmaker Victoria Lean connects personal stories from the First Nation to entwined mining industry agendas and government policies, painting a complex portrait of a territory that is a imperiled homeland to some and a profitable new frontier for others.

Rusty Talk

Rusty Talk Editor:

Adèle Barclay

The Rusty Toque interviews published writers, filmmakers, editors, publishers on writing, inspiration, craft, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, and community.

Unless otherwise stated all interviews are conducted by email.

Our goal is to introduce our readers to new voices and to share the insights of published/ produced writers which we hope will encourage and inspire those new to writing.

Archives

November 2017

February 2017

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

October 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

March 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

May 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

Categories

All

Activist

Adele Barclay

Alex Carey

Alex Leslie

Amelia Gray

Andrew F. Sullivan

Ania Szado

Artist

Author

Bill Bissett

Bob Kerr

Bonnie Bowman

Brian Joseph Davis

Carolyn Smart

Cartoonists

Catherine Graham

Children

Christian Bok

Comedians

Cornelia Hoogland

Daniel Zomparelli

Danis Goulet

David Groulx

David Hickey

David Whitton

Dina Del Bucchia

Directors

Documentary

Editors

Elisabeth Harvor

Elizabeth Bachinsky

Emily Schultz

Erin Moure

Experimental

Fiction Writers

Filmmakers

Francisca Duran

Gary Barwin

Glenn Patterson

Griffin

Griffin Poetry Prize

Heather Birrell

Hoa Nguyen

Iain Macleod

Illustrators

Interview

Ivan E. Coyote

Jacob Mcarthur Mooney

Jacob Wren

Jacqueline Valencia

Jane Munro

Jeffrey St. Jules

Jennifer L. Knox

Julie Bruck

Karen Schindler

Kevin Chong

Laura Clarke

Laurie Gough

Linda Svendsen

Lisa Robertson

Lynne Tillman

Madeleine Thien

Maria Meindl

Marita Dachsel

Matt Lennox

Matt Rader

Media Artists

Michael Longley

Michael Robbins

Michael Turner

Michael Vass

Michael V. Smith

Mike Watt

Mina Shum

Mira Gonzalez

M. NourbeSe Philip

Monty Reid

Musician

Myra Bloom

Nadia Litz

Nonfiction Writers

Novelists

Patrick Friesen

Paul Dutton

Penn Kemp

Per Brask

Performers

Playwright

Poetry

Poets

Priscila Uppal

Producers

Publishers

Rachel Zolf

Ray Hsu

Renuka Jeyapalan

Richard Fulco

Richard Melo

Rick Moody

Robin Richardson

Rob Sheridan

Roddy Doyle

Russell Thornton

Sachiko Murakami

Salgood Sam

Scott Beckett

Screenwriters

Semi Chellas

Sharon Mccartney

Sheila Heti

Short Fiction Writers

Sound Artist

Steve Roden

Tanis Rideout

Tom Cull

Translation

Translators

Travel Writers

Trevor Abes

Tv Writers

Ulrikka S. Gernes

Vanessa Place

Visual Art

Vivieno Caldinelli

Writers

Zachariah Wells

RSS Feed

RSS Feed