RUSTY TALK WITH PAUL DUTTON

This communication was conducted by email between John Nyman and Paul Dutton. John Nyman: At Rusty Talks we often ask writers about their first memory of writing creatively. Your career, however, has focused at least as much on your signature oral performance technique of “soundsinging” as it has on “writing” in any traditional sense, and you have said on several occasions that you see your work as “a continuum; pure music at one end of the spectrum and pure verbality at the other end” (Somerset). Considering this, what is your first memory of engaging in any creative activity, whether musical, verbal, visual, or something in between? Paul Dutton: In my preschool years, when I got pissed off about something, I’d stomp up the stairs, blistering the air with the foulest language I knew: “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Stinkers and Bums!” That, at any rate, is how I have always remembered it, but my eldest sister recently insisted, quite adamantly, that what I shouted was, “Darn it! Rats! Brats! Bums and Stinkers!” And that has made me wonder if I perhaps reconstructed, from abiding family lore, my personal memory of my oft-repeated display of pique, complete with a mental image of my miniature self pounding up the staircase. Whether the memory I hold is truly mine or borrowed from accounts heard from family members, it’s clear that, somewhere along the way, I exercised a bit of aesthetic initiative, reversing the last two terms to create a skippier cadence. JN: What would you say are the similarities and differences between your sound performance and your written work? PD: Oh shit, I don’t know . . . [3 days later (because let’s admit it: I’m writing this, not speaking it)]: Okay. I’ve thought a lot about this. First of all, my work doesn’t in fact readily divide into “sound performance and written”: there are all kinds of gradations and overlaps. As well, there are plenty of similarities and differences within those two categories, not just between them: for one thing, I write print poems in no one style but throughout a wide range, including formal, free verse, minimal, narrative, with line breaks, run-on, found poems, etc. My sound poems range through a variety of styles as well. And then there are the visual poems, which are arguably as much drawn as they are written—if typing a bunch of punctuation marks, as in my Mondriaan Boogie Woogie sequence (two of which appear in Sonosyntactics), can even be called writing. I like to refer to the whole field of visual poetry as “drawing with the alphabet.” So, we’re getting into distinctions and categorization here, which always make me feel uncomfortable. In so much of my work—and in almost everything else in the world—categories overlap or merge. Anyway, there are no consistent similarities and differences between my soundworks and poems for reading (to substitute terms for your two categories). I have linguistic and non-linguistic poems in both of those categories. I have sound poems with words and fluid syntax, and “written works” with no words (single letters or phonemes instead) and fractured syntax. A number of poems fall into both of your categories, some with performance notes, some without; and some whose written versions have shortened passages of what would be extended repetitive material that works fine in performance but would be oppressive in print. Since the late 1990s all my newly created soundworks have been totally improvised and almost exclusively nonsemantic, unlike the painstakingly worked-over poems composed for reading and recitation. I still perform repeatable repertoire works, which are likewise worked over, but I have long since stopped producing new works in that mode. One consistent feature across the various categories that can be applied to my creations is that the individual works proceed out of themselves: I begin with some generative notion—a word, phrase, image, sound, whatever—and find my way by following the poem (or fiction), sensing its direction and development rather than imposing any preset idea of where it will wind up. In a pure-sound improvisation I of course move more rapidly through the process than when I’m working over something in a repeatable form. Another consistent feature is concentration on the sonic qualities of language and of human utterance in general. This is reflected in the titles I’ve given some of my books (Sonosyntactics, Aurealities, and Right Hemisphere, Left Ear) and my two solo CDs (Mouth Pieces and Oralizations). JN: How do you convey your creative efforts to the listener/reader when you have access to only one medium or the other? PD: I’ve partially answered that already in the third and fourth paragraphs of my response to your previous question. Some of my sound poems are thoroughly worked out—what in music is sometimes referred to as “through composed,” though that typically means notating pitch, rhythm, phrasing, dynamics, and tempo, whereas I never specify pitch, rarely specify volume, and generally, both in sound poems and poems specifically for the page, leave various of those elements to be inferred, implying them by punctuation, line breaks, and distribution of the text over the page. I’ve one printed poem for which I’ve provided idiosyncratic diacritics, briefly explained; and several for which, as already stated, I’ve provided explicit performance notes. JN: You often write about numbers—not mathematical equations, but numbers as quirky and surprising participants in dramatic situations. Why this fascination with the numerical? PD: Maybe its compensation for my general innumeracy. You know, a fascination with one’s disability, or an obsession with an unrequited love. JN: Your work contains many poignant references to time, especially in relation to performance and the body. For example “Milk-Cart Roan” opens with breath breathe JN: How does the idea of time connect, or differentiate, the kinds of writing and genres of artwork you engage in? PD: Hmmm. Time. Well, my readings and my musical performances of course operate within time constraints, either very tight (“No more than five minutes, okay, Paul?”) or very loose (“Take as long as you want”). Does that qualify as a connection? Well, here’s a for-sure differentiation: improvised soundworks are created within the time it takes to perform them, but a poem (whether a sound poem or a conventional print poem) that took me months to compose can be read in a matter of minutes or even seconds. And then there’s content: an awful lot of my bookable poems deal with multiple aspects of time, either referring to or reflecting on various temporal conundrums, ambiguities, possibilities, illusions, and incongruities, among other time-related phenomena (like memory, for example). I’ve got a semantically based sound poem entitled “Time” that starts out with that word and moves through a developmental process to arrive at the word “untime”—which is another obsessive notion for me. But I’ll be damned if I can see a way to get any of that kind of content across within a nonverbal sound improvisation. JN: Sonosyntactics: Selected and New Poetry of Paul Dutton is the newest entry in the Laurier Poetry Series, collecting some of the best poems from your nearly 50-year career with an introduction by Gary Barwin and an afterword by you. How did Sonosyntactics come about, and what did you hope to accomplish with the collection? What was it like working with Barwin (who also selected the collection’s poems)? PD: It’s an invitational series, initiated by the publisher or an independent editor, and Gary proposed it to Laurier—without my knowledge, of course, sparing me the disappointment of a possible refusal. Both Gary and I wanted it to be a collection that fully represented the multimodal character of my work and we’re both satisfied that it is. The concept of the series is to present 35 poems by any given author, which we considered unworkable at the outset, so just went our merry way but kept it within range of the more-or-less average page count in the series. I mainly left it up to Gary to choose, but twisted his arm over a few poems I felt had to be in there for one reason or another. He has either a supple arm or a high tolerance for pain, cuz he didn’t cry out too loudly. To switch the metaphor, we saw eye to eye on almost everything. JN: For me, one of the most striking parts of Sonosyntactics is “Lines on a Line of Kurt Schwitters,” a multidirectional matrix of typewriter lines riffing on Schwitters’s “Decide for yourself where the poem begins.” The collection as a whole presents us with a variety of reading challenges whose solutions we do have to “decide for ourselves”: branching paths nested in long footnotes (“Uncle Rebus Clean-Song”), extremely dense and repetitive prose (“A Little Light Love,” “Thinking”), and performance notes far longer than the “poem” they annotate (“Mercure”), to mention just a few. What role does choice play in your writing, both for you as a writer and for your intended or imagined reader? PD: A choice I make with each poem I write is to compose it either with line breaks or as run-on text—what is usually called prose poetry, a term I frankly find pointless. I myself would never designate such works as “A Little Light Love” or “Thinking” as prose. They are poems, plain and simple, and a qualifier such as “prose” is neither necessary nor helpful. Surely what makes a literary work poetry is the character of the writing, not the way the words are laid out on the page. There’s an awful lot of prose getting published that’s written with line breaks. Writing is, of course, very much a matter of making consecutive choices, either instantaneously or over the course of minutes, hours, days, even years. Yeats somewhere (in a poem, I believe) characterizes poets as staying up all night in pursuit of a single word, which is a circumstance I can relate to. Even in this little exercise, I’ve gone back and forth between alternate words or phrases, or else have revised words or passages that days later I found unsatisfactory for one reason or another. As for the reader’s part in this equation, well the first choice is, obviously, to read or not read the material at all. Then a reader can choose to read silently or aloud, to imagine or attempt a performance of poems I’ve provided descriptive notes for, to heed or ignore my line breaks, to interact creatively with the text or let the words glide past, and in the case of “Uncle Rebus Clean-Song” to read the first thread straight through or else wander off down one of the side-trails. I wish I’d not used footnotes for the various narrative branches in that little fiction (which I don’t actually consider to be a poem, by the way), because the footnote implies a secondary status. Nichol used a more satisfactory method in The Martyrology Book 5, where superscripts offer the option of turning to another section of the book in the same font size, so there’s no hierarchical implication. JN: “The Eighth Sea” stands out in Sonosyntactics, both for the range of its performative strategies (from matter-of-fact cataloguing to full-on improvisational soundsinging) and for the political force of its themes: colonial violence, environmental destruction, and the collision of settler and indigenous languages in the Great Lakes region. What do you think the creative techniques you have pioneered throughout your career can contribute to deeply political conversations such as these, both in Canada and abroad? PD: Yikes! I’ll have to leave that for others to say. I do know that my good friend John Beckwith adapted some of the devices used in “The Eighth Sea” for structuring his 2015 oratorio Wendake/Huronia, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Champlain’s arrival in Huronia. I can’t imagine how to calculate the effect such works might have in the social or political spheres, but I suspect that it’s not significant. I prefer direct activist involvement as a more effective and appropriate avenue of influence in those areas. I’m not a fan of what I call propagandart—didactic or utilitarian works—however much I might applaud and revere the causes espoused. I’m out to create, not preach. I prefer to leave any political stances implicit in the artwork, and focus my attention on the aesthetic and spiritual realms, aiming for a subtler influence, more at the level of principle than of advocacy—you know, leading the horse to water and letting it drink or not (aha! another choice for my readers to make). JN: What are you working on now? Where do you want to take your creative practice in the future? PD: The immediate thing I’m trying to get to amid the welter of clerical tasks I have to fulfill in getting my work out either through publication, recording, or in-person performance, is a follow-up to Sonosyntactics, entitled The Poet’s Revenge: UNselected Poetry of Paul Dutton, which will consist of poems excluded from Sonosyntactics , but that I think are worth having out there again. Next will be organizing into a new collection the print poetry I’ve written since my 1991 collection Aurealities. And I’m hoping to, along the way, get my teeth into some fiction that’s struggling to the surface from somewhere within me. And then there’s my soundsinging, solo or in collaboration. My main band, CCMC (the initials stand for whatever you’d like), continues to play within and beyond Toronto. And I’m pursuing concert opportunities for two or three duos I’m in with instrumentalists. Source: Somerset, Jay and Paul Dutton. “Towards the Ineffable: A Conversation with Paul Dutton.” Musicworks 99 (2007). 30-37. <http://doyouconcur.com/articles/PaulDuttonMusicworks.pdf> PAUL DUTTON'S MOST RECENT BOOK |

| Description from the publisher: Sonosyntactics introduces the reader to over forty-five years of Paul Dutton’s diverse and inventive poetry, ranging from lyrics, prose poems, and visual work to performance texts and scores. Perhaps best known for his acclaimed solo sound performances and his contributions to the iconic sound poetry group The Four Horsemen, Dutton is a surprising, witty, sensitive, and innovative explorer of language and of the human. This volume gathers a representative selection of his most significant and characteristic poetry together with a generous selection of uncollected new work . Sonosyntactics demonstrates Dutton’s willingness to (re)invent and stretch language and to listen for new possibilities while at the same time engaging with his perennial concerns—love, sex, music, time, thought, humour, the materiality of language, and poetry itself. |

A Little Light Love

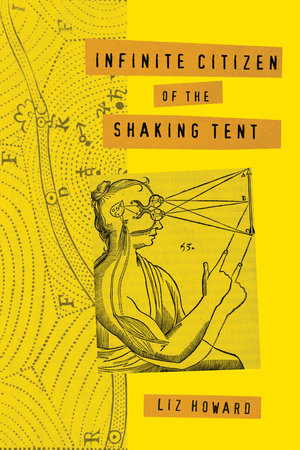

RUSTY TALK WITH LIZ HOWARD, WINNER OF THE GRIFFIN POETRY PRIZE 2016

| | Liz Howard was born and raised in northern Ontario. She received an Honours Bachelor of Science with High Distinction from the University of Toronto. Her poetry has appeared on Canadian literary journals such as The Capilano Review, The Puritan, and Matrix Magazine. Her chapbook Skullambient was shortlisted for the 2012 bpNichol Chapbook Award. She recently completed an MFA in Creative Writing through the University of Guelph and works as a research officer in cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto. |

In my poetry I hunger to reside, if even uncomfortably, within the pyroclastic flow of my own consciousness. What can I offer to anyone? What account is most significant? How do I write about the deeply, darkly personal with rigour and beauty? How to not turn my face away?

Liz Howard: Pie has always struck me as uncanny. There is something repellent for me about the notion of cooked berries or fruit. A berry is best consumed raw, to my taste, at a temperature no greater than being warmed by direct Boreal sunlight in the afternoon hours of July 22nd, 1997. In childhood I witnessed the entombment of thousands of wild blueberries in pie crust. Pie, for me, is a fearful thing, a depravity.

Cake is a different matter. It comes from a box and your mother bakes it for you on your birthday. Cake is therefore a manifestation of filial love. Let us all eat cake. Let it be chocolate, especially.

JV: If you were a Ghostbuster who could bust ghosts using poetry, what poem would you use against a ghost?

LH: I believe I would use Fever 103° by Sylvia Plath. Its intensity, accusations and radical shifts in mood would no doubt cause the ghost to say that it realizes it hasn’t yet gotten over a prior haunting and needs time alone to reconnect with itself.

JV: Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent is very organic and very visceral. I find you're fearless in your pursuit of existential earthly answers. What do you hunger for in your poetry? What do you search out in the world of poetry?

LH: In my poetry I hunger to reside, if even uncomfortably, within the pyroclastic flow of my own consciousness. What can I offer to anyone? What account is most significant? How do I write about the deeply, darkly personal with rigour and beauty? How to not turn my face away? I hunger for moose meat and clarity. I hunger for dreams and to never awake. I hunger for the strangest phrase, for the night to continue, for my father to be alive. I hunger to express the irrepressible effects of being a creature who has born witness to and so far survived the effects of colonial late capitalism.

In the world of poetry I hunger for a feminist utopia wherein not one of us is afraid to name, say or make.

JV: ”No one occupies me like me. And no one / makes me lonelier” In terms of an independent being in a world of mass independent beings, what are your thoughts on breaking free from colonialism now, especially in literature?

LH: Talk about the tie that binds. As in double bind. As in, “I hate you, never leave me.” I was born a problem and I endeavour to remain thus. Kathy Acker wrote, “Life doesn’t exist inside of language: too bad for me.” My life is under threat inside of colonialism and so I must try and write outside it while dwelling within it and paying its bills. It is a cruel madness, unending.

JV: This is your debut collection. How does it feel for you to have your words out there? Tell me about the process of letting go of the work and your book now having a life of its own apart from you?

LH: The feeling is oddly taxidermic. As if I’ve flayed my own skin and transposed it onto a shape that vaguely resembles me, and then that is conceived into a reproducible format. I have been fortunate in that my work has been received well. I have no idea what my book is doing out there without me and this is at once exciting and mortifying.

I feel as though I never really had an opportunity to “let go” of the work. Everything happened and continues to happen so fast. I can barely keep up with my own monstrosity. A rich embarrassment.

JV: What's on the agenda for the future? Is there something you've always wanted to work with outside of literature or as in a collaboration?

LH: The future is the greatest uncanny valley. That being said I suppose I’m working on an extended account of my life and the history of Northern Ontario. I hope to work on a sound-based performance and write about indigenous dance practice. Mostly I hope to craft a life that is liveable for me and be kind to the ones who love me. Fundamentally, I hope to continue to survive.

Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent

McClelland & Stewart, 2015

| Description from the publisher: In Liz Howard’s wild, scintillating debut, the mechanisms we use to make sense of our worlds – even our direct intimate experiences of it – come under constant scrutiny and a pressure that feels like love. What Howard can accomplish with language strikes us as electric, a kind of alchemy of perception and catastrophe, fidelity and apocalypse. The waters of Northern Ontario shield country are the toxic origin and an image of potential. A subject, a woman, a consumer, a polluter; an erotic force, a confused brilliance, a very necessary form of urgency – all are loosely tethered together and made somehow to resonate with our own devotions and fears; made “to be small and dreaming parallel / to ceremony and decay.” Liz Howard is what contemporary poetry needs right now. |

EVERY HUMAN HEART IS HUMAN

I could call this

a streamlet a better

coordinate, simply

lamprey

in the trafficking

style no matter

any purple sky

or blue vapour

tender pine

became women

working the real

number is even

higher

when I was

out already

cunting in the fields for that fallow

had escaped me

in some marsh

of insufficient housing

laughing

all the time Christ thought me

a fossil

I, Minnehaha, a small LOL

fiction antecedent

to quarry a nation

I gave you this name then said

Erase it

RUSTY TALK WITH SORAYA PEERBAYE

The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. [...] I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered.

Soraya Peerbaye: My desire to write about the murder of Reena Virk crystallized after the first conviction of Kelly Ellard was overturned and the second trial was set. The media had framed the case as an example of the rise in “girl violence,” as though the potential aggression of girls and women was a new phenomenon, without recognizing the social hierarchies of race, gender and beauty norms that made girls like Reena so intensely vulnerable. Then it seemed that the legal system could not believe in the guilt of a young, white girl. So the first impetus was political; I wanted to speak to the chasm between those public discourses, and the experience of so many women of colour I knew—those of us who had made such delicate transactions in girlhood to stay out of harm’s way.

As for the poetic—that was a response to the trials themselves. I think anything direct I might have wanted to say was undone by what was unknown, uncertain, denied. By the fact that the young people who testified had so few words to describe Reena herself, her struggle to survive. Even in describing themselves, what they’d done, they couldn’t speak in an embodied way of their own memories. There were salient elements that the trials couldn’t hold because they weren’t directly tied to questions of guilt or motive; yet these were the moments that the witnesses seemed to awaken, to quicken.

There was a profound sense that we, as a culture, were dredging for something, and at the same time eroding it; that the telling and re-telling was creating a crisis not only for the trials and a potential verdict, but also for the lives of these young people and Reena’s memory. Poetry felt like a way of holding these truths and lies, memories, omissions, silences, with regard for the valence of all of it.

PW: Did you look to other elegiac poems or any other works that dealt with grief for examples and guides, and if so, what were they?

SP: Carolyn Forché’s Blue Hour and her anthology Against Forgetting were early inspirations. Other collections I looked to with more intent were Marlene NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and Sachiko Murakami’s The Invisibility Exhibit. I was riveted by their sustained attention to terrible events; with the way they worked with documentation, testimony; race and gender and law; with the lack or loss or disintegration of memory and artifacts; with time. In Murakami’s work, it was also the way she carried that event in her daily life—what seemed innocuous in the ordinary world, and the way it was tainted by the trauma she was carrying.

I’m not sure how much elegy and grief were the driving questions. I didn’t know Reena; it wasn’t my grief. It was more about endurance, maybe closer to vigil. I also read Steven Ross Smith’s Fluttertongue 4: adagio for the pressured surround. It’s an annotated vigil; there’s a violence in its lyricism, in the tension and release between memory, a contemplation of the political, the act of tending to the beloved during a prolonged dying, and the quotidian. I feel the influence of that collection in the Gorge poems in Tell.

PW: Tell’s five sections seem to me to have a kind of circular motion. As a reader, I felt like I started on the outer rim, was sucked into the dense and dark centre, and then was whirled out again. How did you find the arrangement and shape of this manuscript?

SP: I was searching for that shape and energy for a long time, but really only found it in the process of revision with Beth Follett, for which I am very grateful. It needed to be released from chronology, from the sequence of events, the process of ascertaining guilt or innocence. I knew from the beginning that this wasn’t a murder mystery; if Ellard had been acquitted, it wouldn’t have changed the book significantly—the material might have been flung further apart, but still by the same physics.

I think the manuscript works through the turn and return around the same events. The narrative isn’t stable; each turn has the potential to complete a narrative but more so to disturb it—to create other currents, other pools.

Circular, yes. Coming to the verge of something and then whirling outwards. It bears repeating how many trials there were related to the case—from the trials of the young girls charged with aggravated assault, to the trial of Warren Glowatski, to the three trials of Kelly Ellard. I think of it more as a spiral; the witnesses circle around the same questions but at different points of their lives: 13, 15, 19, 21, 27...their lives are changing but tethered to the same forces and the same questions of who they were.

PW: I felt the speaker in these poems questioned racialized experiences and violence without ever expecting to come across a satisfying conclusion. Was that tension deliberate? Did you set out to create a feeling of open-endedness?

SP: Yes and no—it wasn’t so much an intent, but I did want to map it as I experienced it. At the heart of the collection is the girl I was. I had no language as a child, or even as an adolescent, for my experience of race or racism. Finding those words changed the experience and gave me a different capacity to bear it.

I admit I wish I had the assuredness of other poets, who can channel both the tenderness of who we were, and the rage, personal and communal, of our present recognition of that. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is foremost in my thoughts as I write this—the kineticism of her writing emerges from her naming of things through every kind of language that she has, lyrical, critical, activist... and the way those languages catalyze each other.

Law looked for an explicit motive and a binary delineation between the accused and the victim. My dear friend, scholar Sheila Battacharya, once commented on the Reena Virk case as an event “that has no motive but is not neutral.” It’s that I’m trying to get at; the feeling of it being charged with racism, and for that matter with cruelty towards big bodies, androgynous bodies. It’s charged and we feel it but can’t hold it. We don’t often describe the Reena Virk case as a gendered crime, in the way it enforces white feminine hegemony—but it is that, too.

PW: Similarly, although Reena’s attackers were tried for the crime, there’s a sense of another trial that involves the reader and viewers of the event, as well as all Canadians who are unknowing or who stand passively by when bullying takes place. There’s a sense of culpability that can’t quite be washed away. How did you explore the idea of trial and guilt in your writing process?

SP: I think that unlocking questions from the legal proceedings allowed me to consider, what exactly is being asked here? Who do we believe, who do we want to believe and why? One of the statements that didn’t find its place in the manuscript was a riposte by Ellard when she was first questioned by police: “This is Victoria. No one gets murdered in Victoria.” I kind of laughed when I read it—it’s such a bitchy and astute play—a comment on the mindset before the finding of Reena’s body.

I was struck in the trials by the power plays in the courtroom language; how the young witnesses tried to be more formal, in their language and tone, to regain authority over their own memories or claims of truth. The way their voices dropped, their stammering, was so often taken as an indicator of unaccountability, lying or even just dumbness. I wanted to examine the fairness of that, and at the same time undermine the brutal formality of the courtroom in the face of the witnesses’ experience, the authority of adulthood, of prosecution; to reveal what felt like a kind of vulnerability on the underside of the questions. And at the same time there were entire series of examinations and cross-examinations in relation to moonlight, tide, mud, shooting stars—and no one, neither adult nor child, is accountable to the natural world; they talk about it without seeing it.

PW: Can you talk about the difficulties of working with these source texts—the autopsy reports, the testimonies, and any other texts? Was it similar in some ways to writing a found poem?

SP: The source texts were always alive and full of potential for me. “Examination” was probably the only poem I consciously thought of as a found poem. Otherwise, I was trying to intervene more actively with the text, even when the intervention was about creating a relationship between the source, and silence, or unanswerability. There’s a process of critique that is continuous and shifting: sometimes I am questioning, but oftentimes the source unintentionally subverts or asserts itself.

But I guess that’s what a found poem does.

I’ve been thinking about the term ‘rewilding,’ and wondering if what I was responding to was a sense that the legal proceedings were domesticating a discourse around young people, violence, contempt... I turned to archaeological texts, or my conversations with Cheryl Bryce’s words as Lands Manager for the Songhee First Nations, because it reimagined the ecology of Victoria; an antidote to the domesticated way of describing the city’s beauty, the shock that such a terrible crime could have happened in a such a place, a “tea-town.” There is a desire for me to rewild the testimony, to return it to a larger ecosystem, beyond the trials and the verdicts.

PW: The book’s middle section about your own family, identity and girlhood, actually brings the reader closer to understanding and visualizing the invisible details of Reena Virk’s life. Did you hope to bring the reader into spaces that they might not usually venture?

SP: It’s good to hear that. I hesitated to write about myself; I didn’t want to suggest any equation between my experiences and Reena’s. But it became necessary to remember how hard I wanted to be seen; to have that touchstone, even if I couldn’t offer anything of Reena’s life before the night of her death.

There’s guilt for me in this section—that I’m writing this from such a privileged position. I don’t know what I hoped that the reader might feel in relation to my life, except maybe that tension; the difference between the strategies I could use and Reena’s. That I tried so hard to be a good girl, while Reena transgressed.

The popular narrative about Reena Virk was that she was naïve, but there are many of us who think she was extraordinarily courageous—that she insisted on her own presence, her right to be like them, to have what they had. She pissed them off, royally. Shoilee Khan, writer and director of the Bluegate Reading Series in Mississauga, told she remembered being in grade seven and poring over every newspaper article, “enthralled” at the strength of Reena’s desire and her daring. I have a daughter, too, and I’ve doubt that I’d want to warn her, that I’d want her to be safe above all else. But Reena’s agency deserves to be remembered.

Tell: poems for a girlhood

Pedlar Press, 2015

Reena Virk was a girl of South Asian descent who was murdered on November 14th, 1997, in Saanich, British Columbia. At least eight young people participated in the initial assault, while more looked on. Seven of her assailants were girls; five were white. Virk rose from that beating and walked north across a bridge toward home. Her drowned body was found in the Gorge Waterway. In Tell: poems for a girlhood, without a trace of sentimentality and with heart-wrenching courage, Soraya Peerbaye gathers evidence into an entire poetic vision of contemporary adolescent fury and angst.

RUSTY TALK WITH ULRIKKA S. GERNES, PATRICK FRIESEN & PER BRASK

Gernes is an acclaimed poet in Denmark, where she also manages the estate and artistic legacy of her father, the Constructivist artist Poul Gernes. Friesen, from Steinbach, Manitoba, teaches at the University of Victoria and is also a playwright, as is Brask, who teaches at the University of Winnipeg and has worked extensively in theatre. Brask came to Canada after training as a dramaturg in Denmark.

--Rebecca Rustin

Rebecca Rustin: While Frayed Opus for Strings and Wind Instruments eschews direct religious references, Per, you made the remarkable decision to convert to Judaism (For love? I was born to the troubled tribe), and you, Patrick, deal head-on with religious themes in your play The Shunning (Scirocco Drama, 2010), about the Mennonite community you grew up in. Ulrikka's second book was Englekløer (Borgen, 1985), the title translated by Per and Patrick as Angel Claws. Per's work is concerned with, among other things, philosophy (Nietzsche, Badiou), Graeco-Roman classics, and mid-twentieth century European politics. It seems that Patrick and Ulrikka ultimately cleave to the pagan--land, sea, animals, the elements--in terms of anchoring the self to the broader world. How does the divine and/or the pagan (to use the term loosely; I might as well just say 'nature') figure into your thinking about the world, and inform your writing/translation practice? How do you use the subject's direct relationship with nature to find your own path through the dominant narratives of the communities you grew up in?

Ulrikka S. Gernes: I am not an agnostic and I'm even anxious about using such a word, since I do have a firm belief that ”there's more between heaven and earth than flesh and blood” (line from a poem).

As a poet I must never cast my eyes down. I am on the side of the human spirit, the human condition ... I must carry those few drops of water in the palm of my hand through the desert. I once summed it up like this: ”Poetry, in any language, is a language of resistance, resilience, resonance, that speaks from the core and from the rim, from inner and from outer space within the experience of human existence.” One could ask where that thinking comes from? Of course it has to do with the ethics that are fundamental in most world religions and hence are part of our social and cultural ”foundation”, but as Patrick pinpoints it: ”One is a physical and spiritual animal.” I guess that is the point of departure for my work as a poet.

Per Bask: When my wife, Carol Matas, and I got together some forty years ago we quickly became aware that we wanted to make a go of it and that our life together would include children. We decided early on that those children would be raised as Jews—and they have been. That meant that I had a lot of catching up to do and I began to study Judaism. The more I got into it the more fascinated I became and eventually I fell in love with the conversation Jews had had down through the ages about life and God and what we humans owe to each other and to God. I wanted to join that conversation as a member. We are not a religiously observant family, but we celebrate Shabbat and we are committed to a spiritual Judaism that is eclectically informed by different denominations. My recent poetry comes from this outlook, this engagement with life. It has also led me to translate the Danish Jewish thinker Andreas Simonsen.

Patrick Friesen: A community is many things. Some communities have a basic religious approach to life, though every community has its dissenters, or outliers. I found myself resisting the fundamentalist Christian approach prevalent in my community, and central in my family. While the theological aspect was important, the intrusiveness of those who thought they had a right to probe the state of my soul and to judge it was perhaps the most important part of my resistance. I am interested in both the state of my own spiritual existence and in the social and political aspects of world religions. One is a physical and spiritual animal. I doubt I’m a pagan, though that would be a lovely label to carry. I don’t know if there’s one single word that indicates what I am. Some days I feel I’m an atheist, other days an agnostic, and there are even days where I might come close to some kind of Christian mysticism. But I don’t really know. I do feel that essentially I’m a material being with a spirit, and I have a good sense of what happens to matter after death. What I don’t have a firm grip on is what happens with spirit.

RR:I know I said I'd stay away from boring process-y questions, but Patrick, in the interview you recently gave Vancouver's Roundhouse Radio you said something that sounded kind of fun, about the early days of you and Per's collaboration in translating Danish poetry, when he would come sit on your couch and you guys would hammer things out. How does it look when the three of you get together?

USG: Our collaboration has unfortunately mostly taken place in cyber space (not many drinks involved) in a rainbow of emails exchanging suggestions, corrections, comments back and forth, and for me it felt like a complete luxury that two wonderful people on the other side of the world would take such care, use their linguistic strength, intelligence and sensitivity—as well as their precious time—to choose and shift around words in poems and stick by them until they fitted hand in glove into the poem.

PB: Email with the addition of the telephone has made our work possible since Patrick moved to BC.

PF: The three of us never get together physically in order to discuss the translation we’re involved in. Email and telephone is how we communicate. With Per and myself the occasional phone call is essential so that we can hear what we’re doing.

RR: When John Weiners, at the time a prodigious drinker of Carling Black Label beer, won a NEA grant, he simply switched to champagne. What's the silliest thing you've ever done with an unexpected windfall? Would you do something silly with the prize if you won? Why is money such a vexed question with regard to the arts? Is money evil?

USG: Money? Well, rent has to be paid. Honour doesn't buy breakfast. Money; it's tough when you don't have it. I guess the point is to have enough. Money can do great things and change lives, but money itself doesn't interest me. I know that that sounds arrogant and is a sure sign I'm spoilt silly with the privileges of having been born in a wealthy part of the world, but one must remember: life itself is not long! I am sensible with money (grew up in an artist family with no money) knowing that money—or perhaps a windfall?—can buy freedom to do other things such as writing poetry.

There's hardly ever money involved in poetry. Up to now Per and Patrick have basically worked for free. Actually the fee paid for reading at the Griffin is the first real money they get for this book because it is shared between us and that makes me happy (and if we hit the jackpot, naturally that is shared too!).

PB: I’ve never had a windfall. Should one happen I can only say: 7 grandchildren

PF: People of Mennonite background don’t do silly things, surely everyone knows that. But I think investing a windfall would be quite silly. It’s not something I have to worry about.

RR: Patrick's first language was, I think, Low German, Per's was Danish, and Ulrikka, growing up Danish in Sweden, perhaps you learned Swedish, Danish, and English at the same time? How do you all feel about the relationship between English and your mother tongues? Do you wish it were easier to make delicious compound words in English, as you can do in German and Danish? Are there things English can do that Danish can't?

USG: Different languages have different advantages and disadvantages. Certain things are more easily, precisely or poetically expressed in Danish than in English and vice versa. There are words ”lacking” in both languages. One language will have an abundance of synonyms while the other has an empty gap in a particular field. For instance the Danish word døgn, which is a word for day and night together, for the full 24 hours, English, curiously, doesn't have a word for that. Translating døgn you have to either choose day or night or say 24 hours and that can completely shift the meaning and feeling in a poem.

Danish is my mother tongue, the language I feel the most intimately connected to (spiritually and physically) despite the fact that I am born and grew up in Sweden and speak fluent Swedish. It is interesting that somehow mother tongue and mother's milk are almost synonymous—language is part of the nourishment. However, English was a ticket to the whole world in a sense, allowing me to travel and live in other parts of the world. I have a fairly good command of English, but when it comes to the subtle details, the shades and nuances, the flavors, I depend on Patrick and Per.

PB: Those compound words in Danish and in German are usually pretty awful, in my view. English has a much larger vocabulary and I find that endlessly engaging.

PF: Compound words are mostly very useful, but in translating you often have to split compound words in half, or possibly in threes, and then you have lost a lot. Perhaps if you’re lucky you’ll find a compound word in English that approximates the Danish compound word, but it’s doubtful. But you might find a word that catches part of the compound word and adds something new to the poem. Suddenly, the poem changes a little bit, and it’s up to the translator to decide if this change in fact helps the poem in its new language without straying too far from the original.

RR: What kind of music do you like right now? Anybody ever play an instrument? Smash a guitar onstage? Per, you're a librettist. What a beautiful word. Do you sing?

USG: I wish I could sing, or play an instrument! I wish I could express myself without leaving behind a monument to failure ...

Music has this ability to push through barriers in the brain and touch us in a direct and immediate way and hence influence emotions, atmosphere, sentiment, we have little defense toward music, and it is also curious how lines from songs or snippets of tunes and melodies can pop up in your heads triggered by an emotion, or a chemical shift in the body. The same way music can put you in different moods. I used to listen to a lot of music, and I still do, and many different types of music, but find that I ”use” music, sometimes as tools to access certain ”moods”, or to get energy, or to get myself out of a certain mood. Music can pour from an open window and completely blow you away ...

PB: The Rolling Stones never get old for me.

I’ve written two pieces for the composer Michael Matthews, one a piece for actor and cello and the libretto for Matthews’s opera Prince Kaspar. I do not sing. Way back in the mid to late 1960s I played bass guitar in rock and roll bands, eventually dropping the bass and becoming a lead singer (read: screamer). I was never good at either but I love good bass riffs and in my writing and translation it is a bass line that plays in the back of my mind.

PF: I like a lot of different kinds of music. I loved the rock ‘n’ roll of the 60s, especially what was coming out of England in the middle of that decade. I particularly love garage-band records, like Shakin’ All Over by Chad Allen & the Expressions, and what used to be called novelty records, like Surfin’ Bird by the Trashmen or Muleskinner Blues by the Fendermen. I loved the wildness in rock, the letting go, the sheer exhilaration and mad laughter.

I love all kinds of jazz, people like Bill Evans, and classical music, from Mozart to Arvo Part. I love fado and cante jondo. The list goes on. I can read music and took piano lessons, but I ain’t no player, and I’m no singer either, but music plays a central part in all my work.

RR: How do the dramatic scenes encapsulated in each of Ulrikka's poems speak to your, Patrick and Per's, experience in theatre? Have you, Ulrikka, ever been involved in theatre in any way?

USG: I've never tried my hands at writing for the theatre, but when writing poetry I often have this ”stage” in mind where something happens, where people interact, or nothing happens and you wonder why. As a child I loved radio plays. Maybe because we didn't have a TV. I think the attraction was that images developed in my head, I was actively involved and that was very engaging. I still love to listen to radio drama when I'm moving around Copenhagen on my bicycle.

A Danish actress once told me about an exercise her acting group had done where each actor and actress had picked a book randomly. The task was to act improvisations from the texts they randomly chose. Chance had it that she had picked one of my poetry collections and the whole group was surprised how well my poems had worked ”dramatically”. I wish I had been a fly on the wall there.

PB: In addition to that bass line, I need to sense the gesture of a piece before writing or translating. I believe that comes from my theatre training.

PF: In addition to the actual theatrical writing I’ve done, I think there’s an element of theatre in some of my poetry; that is, I often have voices in my poems, implied or actual. There’s a lot of conversation in my work, often internal. I think I always look for that conversational motion in other people’s work.

RR: Ulrikka and Patrick, you've drawn a distinction, in the Afterword to Frayed Opus and in the Roundhouse interview, respectively, between melancholia (Ulrikka) or the doldrums (Patrick), and depression. It seems as though North American culture overclinicizes things sometimes. Or demands that everyone 'think positive.' Would you expand a bit on the subtleties of negative emotion--the kind that calls for medication versus the kind everyone lives with? Anyone: European versus North American approaches? Is there an equal balance of joy and misery in the world?

USG: Patrick suggests reading Lorca and Per points out the importance of visits to the darkness. I absolutely agree! Now, I will be a little bit cheeky and answer your question by guiding your attention to a fantastic painting by Lucas Cranach The Elder because that painting for me sums up melancholia in a beautiful, philosophical and intelligent way. I would prescribe meditating on that painting before taking any medication! We are fortunate to have that painting in the collection of the National Gallery in Denmark so I have seen the original many times and I still go to see it every now and then—when I need a bit of that medicine!

PB: That’s Jacob’s struggle, the struggle we all have with life and the divine—whatever we chose to call that. But depression is real, horrible and not recommended. Melancholy thoughts, visits to the darkness, on the other hand are necessary for reevaluation and getting better at life—I think.

PF: Ah, yes, much has been medicalized which shouldn’t be. I recently heard that grief is now considered a “disease”. We medicalize, and we categorize, to the point of absurdity. Melancholy is essential I think. As are grief and sorrow and even moments of despair. Experiencing darkness is important simply for living our lives, but it certainly plays a part in the creation of art. A lot of the best work is done in “altered states”. But, of course, it’s always a balancing act, a risky business. One can get lost in darkness, or in an altered state. Venturing there requires a certain amount of courage and the strength and pragmatism to get out. Read Lorca on this subject; his poems but also his essays. His concept of duende is central to his literary output.

Frayed Opus for Strings and Wind Instruments

Brick Books, 2015

YOU ONLY LOVE ME WHEN I SMOKE;

RUSTY TALK WITH JACOB WREN

| Jacob Wren makes literature, performances and exhibitions. His books include: Unrehearsed Beauty, Families Are Formed Through Copulation, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed and Polyamorous Love Song (a finalist for the 2013 Fence Modern Prize in Prose and one of the Globe and Mail’s 100 best books of 2014). As co-artistic director of Montréal-based interdisciplinary group PME-ART he has co-created the performances: En français comme en anglais, it’s easy to criticize, Individualism Was A Mistake, The DJ Who Gave Too Much Information and Every Song I’ve Ever Written. He travels internationally with alarming frequency and frequently writes about contemporary art. Connect with him on his blog (www.radicalcut.blogspot.com) or on Twitter@everySongIveEve. |

Wren’s new book Rich And Poor (Bookthug) travels through the mind of a disenfranchised man who decides to kill a billionaire as a political act. The book is told through both the eyes of the assassin and the rich man. Kiarostami’s Close-Up is a fictional film about actual events with the people who experienced the events, thus. Both Wren's book and Kiarostami's film are driven by unreliable characters and events that ultimately play upon the idea of what is art and what is truth in art.

I recently had the chance to talk about his new book, art, politics, literary cliques, and film.

—Jacqueline Valencia

Jacqueline Valencia: I literally just finished reading Rich And Poor and re-watched Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up as well. What brought you to do this for the Lincoln Center?

Jacob Wren : Rachel Rakes invited me to be part of this series I’ve never seen, but seems really awesome.

JV: There is an unreliable narrator in the movie and in your book. What I enjoyed about that is that the man pretending to be the filmmaker and in turn the filmmaker making a movie about that it’s a duality seen in your book, Rich And Poor. These two works explore duality.

JW: It was only when I finished Rich And Poor that it became so clear to me that there were two unreliable narrators. I went back and forth between them. But I do think there is some sense in which all my writing is about paradox or embodies many paradoxes of living that makes it clear that there can’t be a reliable narrator. We’re all unreliable narrators of our own lives. Philosophizing and trying to theorize about life is a kind of unreliable activity.

Rich And Poor is a book about many things, but one of the things it’s about is what we do about capitalism. How can we change it in some way, or can we or is there any possibility, or what are the possibilities? Capitalism seems so overwhelming. Any idea you have to change it or defeat it one can’t be sure it will work. Also, capitalism seems to be able to absorb so much of the opposition. It takes that opposition and makes it a part of capitalism and you can feel it’s hopeless.

I think this puts us in a position of being unreliable, or unknowing, or unsure.

JV: It’s a pretty circular thing because once you make a call to action it gets easily appropriated without one realizing it until it may be too late.

JW: Yeah or it might change things, but not exactly the things you want to change. You’re entering a very unpredictable space.

JV: I noticed the line: “Someday a real rain will come and wash all the scum from these streets.” It’s from one of my favourite films, Taxi Driver.

JW: * laughs * Yeah.

JV: What inspired you to write Rich And Poor besides the idea of capitalism because this reads a lot like the characters in Taxi Driver (Travis Bickel, the disenfranchised taxi driver and Palantine, the politician).

JW: I would say that the origins of Rich And Poor were reading David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5000 Years and a lot of the discourse around Occupy Wall Street and this refocusing of leftist attention on the one percent. Also, how capitalism became less of an abstract.

I was raised to think that capitalism was this abstract post-modern machine, in that Foucault sense, invaded all of our discourse and our ways of understanding the world totally. Capitalism may be that, but it’s also rich people getting richer. And refocusing capitalism on the idea of rich people getting richer and well with all the rich people I was thinking, why don’t we just kill them? It’s probably just a few hundred or a few thousand people. Why not the French Revolution?

This unnamed protagonist who decides to kill one specific billionaire—it’s a classic cinematic image for the loner who wants to do something good in the world, but maybe where we question him is in Roberto DeNiro in Taxi Driver.

Jacqueline: There are many layers in watching a film. We have the film that is presented to the viewer and the film that continues playing in the viewer’s brain after they’ve left the theatre. This is one of things that really got me about Kiarostami’s Close-Up. I forgot who says it, but the line that stuck with me was: “Spite is a veil to conceal art.” Some of the passages in your book also stand out in much the same way.

My point is, I wonder if Kiarostami had that in mind, the idea of the film as an extended part in a viewer’s mind.

JW: Yes. Close-Up is such a film about art and what power it has in the world or what power it doesn’t have in the world. And the way art is or isn’t a lie or is or isn’t truth.

It’s a Tolstoy quote: “Ill will is the veil that covers art.”

JV: The unnamed billionaire in Rich And Poor starts a poetry foundation. He forms it as a kind of conceit or way for him to find out what poetry or art is. And sometimes he gets it and sometimes he doesn’t, especially when it comes to activism. It’s really interesting especially with current controversies within the poetry community. What did you want to explore in including that?

JW: I would say all of my books are somehow about the relationship between art and politics. There are positive and negative relationships there. This is one cynical relationship between art and politics.

JV: How about art and politics within Close-Up?

JW: That’s fascinating because you have the con man who is somehow using the power of art to gain something. He’s trying to gain symbolically a sense of self in the world and a sense of power. Then there is the financial aspect to it too where he’s trying to get money.

JV: Do you really think he was trying to get money though?

JW: No, I mean, he probably wasn’t out to get money. He does need money. He’s using everything at his disposal. And he is an autodidact and I’m also an autodidact.

The politics in Close-Up are very complex and very paradoxical.

JV: That’s why it leaves you still thinking after you’ve left the film. This goes back to your book. I think that after a reader reads a book, like a viewer finishes a film, there’s another book inside the readers brain. So as I read your book and I do a bit of activism, it seeps in there and resonates. There’s a big aspect of activism in your book. What do you think will be the next activist wave in poetry or literary culture?

JW: I’m really bad at predicting the future. Whenever I try and predict the future I am always wrong. Definitely we are living in a kind of golden age of protest in the moment. There’s been an enormous degree of powerful effective protest all around the world in the past ten years. Not quite sure when it started. This protest also connected to the fact that the injustices, let’s say economic inequality, are not only becoming greater but more visible and more obvious.

I grew up in the eighties and I think of shows like Lifestyles of The Rich And Famous where this kind of wealth was cast in a positive way. Maybe that can still happen now, but I think people would be more disgusted about it now than they were then when it was romanticized or sensationalized and made for pure entertainment.

JV: I think that nowadays people aren’t listening to the people who are doing the real work out there. I think poetry is very political by nature, but through all the cliques and the award-world spectacle, we don’t hear or get to read beyond what is told to us. There are so many writers that don’t get heard for various reasons (racism and sexism). That’s my biggest problem with the world of literature.

JW: I always think the art institutions, the publishers, maybe who are now called the gatekeepers ... what am I trying to say? The most political work is often not the most successful, sadly.

JV: I guess what I’m trying to say is that we romanticize what we do get to hear, but don’t hear the rest of the people out there. Not everyone is getting their say.

JW: There’s a lot of people out there with a vested interest in keeping the status quo in place. When you have a desire to change the status quo and you don’t see a change, you’re pushing uphill. That’s why it’s so important and that’s why it’s so difficult.

JV: Do you think Rich And Poor is a political work?

JW: Yeah. I mean, almost to a fault. It’s very obviously about politics in complex ways.

JV: It feels and reads like an activist work or a manifesto of sorts, which I enjoy and why I mention whether you think it is political or an activist work.

JW: I hope so, but there’s a danger in activist art to become simplistic. I struggle so much to do something that is both activist and political, but still full of paradox resonance, questions, and being unsure and see if you can have both at the same time.

JACOB WREN'S MOST RECENT BOOK

Rich and Poor

Book Thug, 2016

Occasioned by the release of Rich and Poor (BookThug), a rare work of literary fiction that cuts into the psychology of politics in off-kilter ways, Jacob Wren joins us to introduce Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up—a masterful exploration of the nature of truth and cinematic illusion, with a distinctly offbeat sense of humor—followed by a discussion and book signing.

RUSTY TALK WITH HOA NGUYEN

| Hoa Nguyen is the author of As Long As Trees Last, Red Juice, and the forthcoming Violet Energy Ingots (all from Wave Books). She teaches poetics at Ryerson University’s Chang School, in Miami University’s MFA program, at the Milton Avery School for Fine Arts at Bard College, and in a long-running, private workshop. Hoa can be found on the web at http://www.hoa-nguyen.com. |

W]hat matters to me in poetry is when poetry risks saying something and addresses the complicated mess that is modernity.

When you are inspired by the personal? Is there a way you go about writing your poetry with it? Is there a process whereby you try to be conscious of the subject you are writing about or do you allow it to flow?

Hoa Nguyen: I guess I do both. I'm writing simultaneously about my mother's life and about Vietnam as a place. Vietnam and Vietnamese women tend to be portrayed as a stereotype and a one-dimensional monolith in the North American imagination (both often serving to center European experiences)—I'm writing in response to these conditions.

One way I get into my process for this series in particular is to work with the I Ching. It also involves many source texts including a small arsenal of Vietnamese folk tales, myths, and children stories—and research.

JV: On social media you're very outspoken when you see an injustice and are willing to take a public stand. It's fearless. What drives you to that fearless place? What matters to you in poetry?

HN: I've always been a champion of and rooted for "the underdog"—probably from my experiences with xenophobia, stereotypes, and ordinary racism. Maybe I'm a bit of a fighter by nature. Nothing makes me see red faster than an injustice.

I've come to think that this, my temperament and resilience and willingness to address things head-on, helped to ensure my survival—that I managed to persevere in part due to sheer grit, despite the disadvantaged circumstance of class and race.

I guess in a related way, what matters to me in poetry is when poetry risks saying something and addresses the complicated mess that is modernity. In poetry, I do not care for the cutesy or exploitive sentimentality or ironic posturing or empty abstraction.

JV: So much in your collection Red Juice spoke to me. Motherhood, contrasts of parental homelands with the American experience, etc. One poem in particular felt like a bridge of childhood and adulthood (“Untouched Bubble Gum Me”). You experiment with experience in it, a playfulness mixed with a keen analysis in just a few words. What excites you about poetry today as an expressive and experimental medium?

HN: Thanks—I'm fond of that poem, too. I love when poems disrupt expectations, are dissonant, cut and bend in unexpected ways, are sonically interesting, and allow me as reader to participate in the meaning-making of the poem.

JV: What are you working on now?

HN: I'm trying to work myself out of a stall on my linked narrative project (mostly that looks like avoidance, ha ha)—and writing each week in the workshop I have run for the last 17 years. Right now, I'm writing through the collected poems of Frank O'Hara (we are in the Lunch Poems section of the work: so great). I'm also prepping to write through the poems of John Wieners—so lots of related reading: essays, his letters and journals, etc.

Meanwhile I'm preparing for a couple of talks, one at Hamilton College, where I'm revising and updating a talk I gave at Naropa's Jack Kerouac School in February that Bhanu Kapil wrote about here. The other talk is on pedagogy of teaching poetry to be delivered in Seattle for the Bagley Wright Lecture Series on Poetry. And some consulting work in there: reviewing a graduate thesis and a poet's rough manuscript.

JV: If you weren't a writer or a poet, what you like to do?

HN: I think I would be a healer in the Green Witch tradition and continue to read tarot. As someone who is drawn to and has a knack for teaching, I would probably also run workshops for both pursuits.

HOA NGUYEN'S MOST RECENT BOOK

RED JUICE: POEMS 1998-2008

Wave Books, 2014

| Description from the publisher: Red Juice represents a decade of poems written roughly between 1998 and 2008, previously only available in small-run handmade chapbooks, journals, and out-of-print books. This collection of early poems by Vietnamese-American Hoa Nguyen showcases her feminist Ecopoetics and unique style, all lyrical in the post-modern tradition. Nguyen's poems are swift, conversational, playful, funny, angry, fully present and self-aware. |

Haunted Sonnet by Hoa Nguyen

RUSTY TALK WITH TANIS RIDEOUT

Tanis Rideout: I didn’t really start writing, at least as far as I remember, until quite late. I wrote for classes, of course, terrible poems for assignments, but I didn’t write for myself.

I have very early memories of reading on long road trips out to the east coast, curled up in the trunk of our hatchback, something that I’m sure is very illegal now, but not writing.

Rather when I was little I would play at being a scientist. I had a lab in my closet. I probably wrote some lab reports. Maybe that counts.

TC: You are both a novelist and poet. Does each format require a different ways of thinking? Do your habits of mind or process change depending on whether you are writing poetry or prose?

TR: I’m not sure that they so much require different ways of thinking, as they have slightly different foci. I use a lot of the same tools in both though. Language—the sound of it, the rhythm of it—is of fundamental importance to me in both realms, using it as the building block of voice, POV and the like. I think I bring that from the poetry world to the prose. I think voice and arc are things that I bring from the prose world and use them in different ways in poetry.

What I will say is that I cannot write poetry if I’m not reading it. I think more in prose than in poetry for sure.

TC: What is the best piece of writing advice that you’ve been given? Have you been given any bad advice?

TR: The best advice—keep going. I sort of feel like the poster child for stick-to-it-ness sometimes.

And for me, keeping going isn’t just about perseverance in general, but also about trying to keep pushing at the work, not letting it stand, but editing, changing, keep making it better, stronger both on specific projects and in the broader sense.

The other really good piece of advice I got was from Joseph Boyden just as my novel was about to come out. He said, "You’re not one book. You better already be thinking about the next thing."

Bad advice--maybe I just ignored it, or I had good teachers, because nothing is really coming to mind. Rather, I think I tend to know whether or not something will work for me, and if it won’t I don’t follow it.

TC: Both your novel and your poetry collection are built on the architecture of historical fact—George Mallory’s third attempt to reach the summit of Mt. Everest inspires Above All Things, while Arguments with the Lake draws on the history of Marilyn Bell and Shirley Campbell, two teenage distance swimmers who rose to fame in their attempts to swim Lake Ontario in the 1950s. What is it that attracts you to history as a jumping off point for fiction?

TR: I love history. I love historical fiction. I certainly think when I started writing, it was easier for me to see the drama in something far removed from me, from my immediate world, and I think there’s a component of fantasy in that kind of writing for me—exploring different times, thinking of who people might have been in those times. And they’re both such great stories: the possibilities they provided were exciting to me.

I think with both those stories it was the character as much as the circumstances and setting that drew me in.

TC: Both Above All Things, and Arguments with the Lake, are built on early-to-mid nineteenth-century tales of human attempts to triumph over nature. What do you find compelling about these narratives? Is the work of a writer analogous to the tasks your heroes set for themselves?

TR: I think in some ways there is some comparison amongst swimming long distance, climbing, writing a novel. They’re all decisions that you have to keep making. You don’t decide to just do it and that’s it. You have to make the decision each day, with each stroke, each step. And I like how that’s also really what life is too—deciding each day, who you want to be, how you want to live. It’s all micro decisions.

I think these human versus nature stories really appeal to me because they terrify me. Movies like K2 or Touching the Void—those are my horror movies. They scare me far more than zombies or haunted houses or what have you. How we pit ourselves against the world or try and live in it, whether we try to conquer it or embrace it, there’s something endlessly interesting about that. How powerless we are in the face of nature, and how deep that can make people dig.

TC: In both of your books, geological entities (Everest, Lake Ontario) are more than simple features of the landscape—they become entities with whom your characters form intimate relationships. In the first pages of Above All Things, Ruth says to George, “tell me about this mountain that’s stealing you away from me.” Likewise, in Arguments with the Lake, we learn that Marilyn retires from competitive swimming, telling the papers that “there’s no room in a marriage for a lake.” How, in your work, does nature triangulate human relationships?

TR: We’re intimately connected to place. It’s something I continue to think about. I lived in a number of landscapes growing up and I’m really interested in how those things inform us personally, artistically.

And I think that we really only begin to understand ourselves and the world when we engage with landscape—this thing that is bigger than us, but that we’re a part of. I think narrative is connected to place and it’s the way I’m best able to understand landscape and environment. I’m not sure I can separate them out.

TC: Your stories of nineteenth-century triumph over nature seem uncannily premonitory. I cannot, for example, think of the legacy of Mallory without also thinking about contemporary images of Everest as strewn with garbage and besieged by long lineups of rich thrill-seekers waiting for their chance to plant their flag. How do you understand these nineteenth-century narratives from our current moment of environmental collapse?

TR: For me the past landscape and its treatment are absolutely connected to what they are today. You can see in the initial attempts on Everest these precursors to what it has become. Even at the time these were well-to-do men, who could take time away from work, pay most, if not all, of their own way to the mountain, etc. The notion of conquering, of owning, or taking over, is part of what I hope we’re starting to examine in terms of environmental consciousness now. I certainly was thinking about the current state of the mountain, or the lake, while I was writing, and wanted the work to hopefully gesture to that without being anachronistic, without spelling it out. But the men leave their trash there. The mountain is already becoming ugly and scarred by them. The remains of those expeditions still occasionally show up.

TC: You do environmental justice work around Great Lakes water protection and preservation. How does this work inform your writing?

TR: I’ve been doing work with Lake Ontario Waterkeeper for several years now. Arguments grew out of my relationship with them, with how they asked me to start thinking about the lake, to start taking ownership of it, responsibility for it. It’s something I think about a lot now, when travelling, when reading. It’s been a new lens through which I view how we interact with much of the natural world—where we live, how we build, who we create.

I’m not entirely sure how this will continue to come out in my writing, other than to say that it’s something that is generally there in the back of my head and so inevitably percolates in some ways.

TC: You are writer-in-residence at Western this year which entails, among other things, working with many young writers who learning writing fundamentals. Has helping these students made you reflect on your own writing? If so, how?

TR: Writing is writing is writing. The tools are always the same. It’s actually been really fantastic to read other people’s work on a weekly basis. Regardless of skill level, when I read someone’s work closely and then sit to talk with them about where it could go, what might make it stronger, it’s then something that returns to me when I approach my own work.

If I talk with someone about how their character needs to want something, I then realize, well, so should mine. Or if I’ve just chatted with someone about POV or tense or something, it’s then something I’m thinking about very specifically when I sit down again.

TC: What are you currently working on?

TR: I’m working on a new novel. There are no mountains or lakes in it. Well, not really. So far.

TANIS RIDEOUT'S MOST RECENT BOOKS

ARGUMENTS WITH A LAKE

WOLSAK AND WYNN, 2013

In 1954, at the age of sixteen, Marilyn Bell became the first person to swim across Lake Ontario. It brought her fame and adulation; her life seemed charmed. Enter Shirley Campbell, another young swimmer whose accomplishments were poised to rival Bell’s, but in falling short in her own attempts to cross the Great Lake, she found herself spiralling out of control into a life of addiction, petty crime, and personal tragedies.

Tanis Rideout weaves the tales of these two remarkable women together in a series of stunning, lyrical poems. It is a story of courage and triumph, but also one of adversity and redemption. This is an exhilarating book of poetry, at once tender and terrifying; like a cold dip in Lake Ontario, it will engulf you and leave you breathless. Arguments with the Lake confirms Rideout’s arrival as a major new talent in Canadian letters.

Marilyn, mid-lake

Branched in their brains makes ninety degree turns, orients

by atmospheric odor.

The lake’s skin smells of a father’s garage: gasoline, aftershave

and repeating Sunday leftovers. A refrain on the tongue

pasted with pablum and honey: North.

Swim north and I’ll find you. But there’s no moon, no

line where the city, meets the sky, meets the offing.

The body is an astrolabe, the pull of home in her skull.

RUSTY TALK WITH CAROLYN SMART

Carolyn Smart. Photo credit: Bernard Clark

Carolyn Smart. Photo credit: Bernard Clark I wanted to write about people on the margins of society, and it is important to me that I saw them clearly, with respect and a lack of judgment [...] to widen the gaze, and let the characters breathe.

Carolyn Smart: After writing my memoir At the End of the Day (Penumbra Press, 2001) I was tired of telling my own story and longed to lose myself in something new. When Myra Hindley died in November of 2002 I found myself staring at the very different photographs that appeared in two obituaries and wondering who this woman really was. At that same time, I had been invited to read my poetry in a performance poetry series and leaped into writing a new poem specifically for performance purposes, something very different from what I had written before in tone and content. I immersed myself in the life and history of Myra Hindley, and tried to imagine life through very different eyes.

And yet, to make her story (and the stories in the six poems that eventually followed and became Hooked: Seven Poems) feel authentic, I accessed my own emotional life, my memories, my experience, and translated them to the page as I had done with all my previous work. If a poem doesn’t feel emotionally honest to me, I know it’s not working. In the end, I found that Hooked was more revealing of my own emotional truth than anything I had written before. For that reason I find it hard to watch the stage versions of the poems, as I feel so exposed. It is very much a collection about vulnerability, about choices and danger and addiction and love, and I wanted to write about these things in the context of women who fascinated me, and could maintain my full attention for as long as it was necessary to translate them to the page. I demand a lot for full engagement; I have a short attention span and am somewhat fickle. I searched and discarded and found what I needed, and I am still in love with some of the seven women to this day.

AB: Careen tells the story of Bonnie and Clyde. What drew you to this dusty, bloody pocket of history? Why did you choose to tell this story?

CS: To reveal previously untold truths has been an obsession in my writing for nearly two decades, and the story of the Barrow Gang is simply a continuation of this. Many people of my age watched the 1967 film of Bonnie and Clyde and believed it factual, but reading the first person accounts of the gang (Blanche Barrow and W.D. Jones both told their stories) or the recent biography Go Down Together (Simon & Schuster, 2009) by Jeff Gwynn, it’s clear that the film was far off the mark. To know that both Clyde and Bonnie were physically handicapped and mainly lived in their car was a game-changer for me. And more personally, my maternal grandfather Harry Van Tress was a failed gunrunner who lived out his last years in penury in Laredo, Texas, and I have long wondered about him, about the Texas of the depression and the dustbowl, about hunger and the desire to break free from poverty by any means at hand. I wanted to write about people on the margins of society, and it is important to me that I saw them clearly, with respect and a lack of judgment. This is something I was adamant about in the writing of Hooked—to widen the gaze, and let the characters breathe.

AB: Careen carries many characters with distinct voices as they tell the beginning, action, and aftermath of the story of Bonnie and Clyde and their gang. How did you manage the vast cast of voices? How did you keep track of them as discrete entities and yet know when to bring them together to create a coherent atmosphere?

CS: When thinking about the Barrow Gang I realized there was so much to tell about the time and place they were living in that it had to be revealed by multiple voices. As in any group, the characters were markedly different and I tried to reveal their realities and backgrounds through their own tales. It was easy to differentiate them as many of their individual stories are fascinating. They had to be resilient and resourceful to survive all they did: the fear and the restlessness, the hard scrabble of daily life.

AB: Archival newspaper articles and Bonnie Parker’s poetry both anchor Careen amidst the cacophonic stream of voices. The newspaper clippings let the dramatic monologues breathe, almost like a Greek-chorus, and Parker’s poetry lends the collection a mythical, almost prophetic valence. I’m curious about the process of culling from the archives. How did you know what to include? What were hoping to achieve by integrating the historical material into the collection? Also, what do you think of Parker’s poetry? What struck you about it?

CS: I used the newspaper reports for two reasons: to clarify the narrative, and to give some sense of how the general public followed their exploits. Bonnie and Clyde were made famous and then torn down by the press; their fame was very bright and short-lived; the nuances of realism were lost in the dust. The fact that Bonnie never killed anyone, that they fell on their knees every single night to pray, that they starved and lived in terror, that the last six months of Bonnie’s life Clyde often carried her in his arms as she could no longer walk, that they loved their mothers dearly, that they travelled with a saxophone, a Remington typewriter, a rabbit, and a dog—these facts don’t jive with how we imagine them: wearing fancy clothes while leaning on a stolen car, cigar in mouth, pointing a long gun, sneering at death.